NILS4 will be conducted in late 2025 to 2026 and reported upon in 2026.

There’s currently a national target in Australia about strengthening Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages by 2031. This is Target 16 in a policy framework called Closing the Gap. Zoe and I talk about how language strength can be measured in different ways and how the team have chosen to ask about language strength in this survey in ways that show clearly that the questions are informed by the voices in the co-design process.

Then we discuss the parts of the survey which ask about how languages can be better supported, for example in terms of government funding, government infrastructure, access to ‘spaces for languages’ and access to language materials, or through community support. The latest draft of the survey also mentions legislation about languages as a possible form of support. This is great; the data should encourage policy makers not to intuit or impose solutions, but rather to listen to what language authorities are saying they need. What I especially noticed in this part of the survey was the question about racism affecting the strength of a language – or reducing racism as a form of supporting languages – so I ask Zoe to tell me what led the team to include it.

We go on to discuss the enormous efforts and progress underway, and the love which many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities around Australia have for language maintenance or renewal. People may get the impression that language renewal is all hardship and bad news because a focus on language ‘loss’, ‘death’, or oppression pervades so much of the academic and media commentary. But Zoe and I both recently met in person at a fabulous, Indigenous-led conference in Darwin called PULiiMA in which delegates from 196 Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander languages participated. That’s just one indication of the enormous effort and progress around Australia, mainly initiated by language communities themselves rather than by governments. We talk about why, in this context, it’s important that this survey also has section about languages ‘flourishing’ and being learnt.

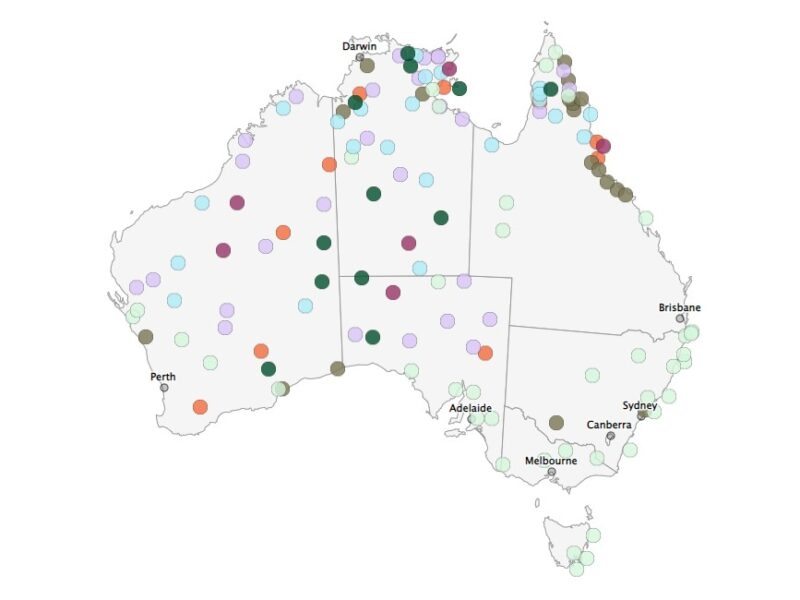

Language groups that participated in NILS3

We discuss the plans for reporting on the survey; incorporating the idea of ‘language ecologies’ was one of the biggest innovations in the National Indigenous Languages Report (2020) about the 3rd NILS and continues to inform NILS4. Finally, we talk about providing Language Respondents and communities access to the data after this survey is completed, in line with data sovereignty principles.

The survey should be available for Language Respondents to complete, on behalf of each language, in late 2025. AIATSIS will facilitate responses online, by phone, on paper and in person. If you would like to nominate a person or organisation to tell us about an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander language, please contact the team at [email protected]. Respondents will have the option of talking in greater depth about their language in case studies which AIATSIS will then include as a chapters in the report, as part of responding to calls in the co-design process to enable more access to qualitative data and data in respondents’ own words.

If you liked this episode, support us by subscribing to the Language on the Move Podcast on your podcast app of choice, leaving a 5-star review, and recommending the Language on the Move Podcast and our partner the New Books Network to your students, colleagues, and friends.

Transcript

Alex: Welcome to the Language on the Move Podcast, a channel on the New Books Network.

My name is Alex Grey, and I’m a research fellow and senior lecturer at the University of Technology in Sydney in Australia. This university stands on what has long been unceded land of the Gadi people, so I’ll just acknowledge, in the way that we do often these days in Australia, where we are. Ngyini ngalawa-ngun, mari budjari Gadi-nura-da and I’d really like to thank

Ngarigo woman, Professor Jaky Troy, who, in her professional work as a linguist, is an expert on the Sydney Language, and has helped develop that particular acknowledgement.

My guest today is Zoe Avery, a Worimi woman and a research officer at the Centre for Australian Languages. That centre is part of the Australian Institute for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, which we’ll call AIATSIS. Zoe, welcome to the show!

Zoe: Thank you! I’m really excited to be here and talking about my work that I’m doing at AIATSIS.

Alex: Yeah, so in this work at AIATSIS, you’re one of the people involved in preparing the upcoming National Indigenous Languages Survey. This will be the fourth National Indigenous Languages Survey in Australia. The first one came out now over 20 years ago, in 2005.

This time around, you and your team have made some really important changes to the survey design through the co-design process. Let’s talk about that. Can you tell us, please, what is the National Indigenous Languages Survey, what’s it used for, and how this fourth iteration was co-designed?

Zoe: Yeah, so, the National Indigenous Languages Surveys, or I’ll be calling it NILS throughout the podcast, they’re used to report the status and situation of Indigenous languages in Australia, as you mentioned. This is the fourth one. The first one was done all the way back in 2004 and, the third NILS was done about 6 years ago, in 2019. So it’s been a while, and it’s kind of just to show the progress of how, languages in Australia are being spoken and used, and I suppose the strength of the languages, which we’ll kind of go into a bit more detail. But the data is really important, because it can be used by the government to develop, appropriate language revitalisation programs or understand the areas that require the most support, but it can also be used by communities, which is really important as well.

And so, NILS4 has been a little bit different from the start compared to previous NILS, because the government has asked us to run this survey in order to measure Target 16 of Closing the Gap, which is that by 2031, languages, sorry, by 2031, there is a sustained increase in the number and strength of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages being spoken.

So, the scope for this project is much bigger than the past NILS, and AIATSIS has really prioritised Indigenous leadership in the design, and will be continuing to prioritise Indigenous voices in the rollout and reporting of the results of the survey.

So, because this is a national-level database, and we want to make sure as many languages as possible are represented, including previously under-recognized and under-reported languages, including sign languages, new languages, dialects. It’s really important that we have Indigenous voices, prioritized throughout this entire research process. And we want to make sure that the questions that are being asked in the survey are questions that the community want answers to, whether or not to advocate, to the government that these are the areas that need the most support, the most funding, or whether or not the community want that data for themselves to help develop, appropriate, culturally safe programs.

So what we did is we had this big co-design process, this year to design the survey. We had 16 co-design workshops with Indigenous language stakeholders across Australia, and this was, these workshops were facilitated by co-design specialists Yamagigu Consulting. We had, in total, about 150 people participate in the co-design process, and of these 150 people, about 107 of these were Indigenous. And so these Indigenous language stakeholders included elders, language centre staff members, teachers, interpreters, sign language users, language workers, government stakeholders, all sorts of different people that have a stake in Indigenous languages, for whatever reason. And we had 8 on-country workshops, which were held in cities around Australia, and 8 online workshops as well, which helps make it easier for, people that kind of came from different places, and weren’t able to come to an in-person workshop.

Alex: That’s a huge… sorry, just congratulations, that sounds like it’s been a huge undertaking. So many people, so many, so many workshops, well done.

Zoe: Yeah, it has been huge, and we’ve had so many different people from a variety of different language contexts, participate as well. So, the diversity of language experiences that were kind of showcased at these workshops was immense and has had a huge impact on drafting the survey, which is obviously the whole point of the workshops, but yeah … We took all the insights from the co-design workshops, we analysed them, thematically coded everything, and started incorporating everything into the survey. And then we went back to the people who participated in the co-design workshops and held these validation workshops so we could show them the draft of the survey, show them how we had planned on incorporating all of their insights, you know, that we weren’t just doing it for the sake of ticking a box to say, yes, we’ve had Indigenous engagement, but we were actually really wanting to have Indigenous input from the start, and right until the end of the project. And we had really good feedback from the validation workshops, and it is, you know, not just a massive task running these workshops, but also, making sure that everybody’s listened to, and sometimes they were kind of contrasting views about how things should be done, and yeah, we wanted to make sure that we had as much of a balance as possible.

We also consulted with the Languages Policy Partnership, which are kind of key workers in Indigenous languages policy and, advocacy. They’re kind of leaders in the Closing the Gap Target 16 that I was just talking about, so their input and advice has been really important to us, as have consultations with the Australian Bureau of Statistics and the Mayi Kuwayu Study of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Wellbeing. So yeah, there’s been a lot of input, and we’re really excited that we’re at the point now where we’re finishing the survey! Dotting all the I’s, crossing all the T’s and getting ready to start rollout soon.

Alex: Yeah, well, I mean, one would hope good input, good output! You know, such a huge process of designing it. You should get really well-targeted, really informative, useful results.

And you’ve mentioned a few things there that I’ll just explain for listeners, because not all our listeners will be familiar with the Australian context. It’s coming through that there’s enormous diversity of Indigenous peoples and languages in Australia, so to explain a little bit, because we won’t go into this in much detail in this interview, Zoe’s mentioned new languages like, contact languages, Aboriginal Englishes, Creoles, like Yumplatok, which comes from the place called the Torres Strait. If you’re not familiar with Australia, that area is between Australia, the Australian mainland, and Papua New Guinea, in the northeast. And then there’s an enormous diversity of what are sometimes called traditional languages across Australia, both on the mainland and the Tiwi Islands as well. So we have a lot of Aboriginal language diversity, and then in addition, Torres Strait Islander languages, and then in addition, new or contact varieties.

Zoe: Sign languages.

Alex: And sign… of course, yes, and sign languages. Thank you, Zoe. And then you’ve mentioned Target 16. So we have in Australia a policy framework called Closing the Gap. For the first time ever, the current Closing the Gap framework includes a target on language strength.

But as the survey goes in to, language strength can be measured in different ways. So how have you chosen to ask about language strength in this survey, and why have you chosen these ways of asking?

Zoe: Yeah, so, along with, kind of, Target 16 of Closing the Gap, there’s an Outcome 16, which is that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures and languages are strong, supported, and flourishing. So it’s important for us in the survey to, kind of, address those kind of buzzwords, strong, supported, and flourishing. But it is very clear, from co-design, that the widely used measures of language strength don’t necessarily always apply to Australian Indigenous languages. So these kind of widely used and recognised measures of how many speakers of a language are there, and is the language still being learned by children as a first language? These are not the only ways of measuring language strength, and we really wanted to make sure that we kind of redefined language strength in the survey based off Indigenous worldviews. So, language is independent [interdependent] with things like community, identity, country, ceremony, and self-determination.

How do we incorporate that into the survey? So we’re still going to be asking questions, like, how many speakers of the language are there? What age are the people who are speaking the language, but we’re also going to be asking questions on how many people understand the language, because people may not be able to speak a language due to disability, cultural protocol reasons, or due to revitalisation, for example. But they can still understand the language, and that can still be an indication of language strength. We’re also asking questions about how and where it’s used. So, do people use the language while practicing cultural activities, in ceremony, in storytelling, in writing, just to name a few? We know that Indigenous languages are so strongly entangled with culture and country, and it’s difficult to measure the strength of culture and country. But we can acknowledge the interdependencies of language, culture, and country, and by asking these kinds of questions, we can get some culturally appropriate and community-led ways of defining language strength.

Alex: And that’s just going to be so useful for, then, the raft of policies that one hopes will follow not just the survey, but follow the Target 16, and even once we get to 2031, will continue in the wake of, you know, supporting that revitalisation.

Zoe: Yeah, absolutely, and I think that, another thing that we heard from co-design, but just also from Indigenous people, in research and advocacy, that language is such a huge part of culture and identity, that by, you know, developing these programs and policies to help address, language strength, all the other Closing the Gap targets, like health and justice and education, those outcomes will all be improved as well.

Alex: Yeah, I guess that’s why, in the policy speak, language is part of one of the priority response areas for the Closing the Gap. And I noticed this round of the survey in particular is different from what I’ve seen in the earlier NILS in the way it asks questions, which also appears to reflect the co-design. So, for example, these questions about language strength, they start with the phrase, ‘we heard that’ and then a particular kind of way of thinking about strength. And then another way of thinking about strength might be presented in the next question: ‘We also heard that…’. So on, so on. So, is this so people trust the survey more, or are you conscious of phrasing the survey questions really differently compared to, say, the 2019 version of the survey?

Zoe: Yeah, absolutely we want people to trust the survey, and understand that we respect each individual response. Like, as much as it’s true, we’re a government agency, and we’ve been asked to do this to get data for Closing the Gap, we want language communities to also be able to use this data for their own self-determination, and we want to try and break down these barriers for communities and reduce the burden as much as possible. So, making sure that the survey was phrased in accessible language, and the questions were as consistent as possible.

But yeah, we wanted to make sure that we were implementing insights from co-design, but making it clear in the survey that we didn’t just kind of come up with these questions out of nowhere, that these were co-designed with community and represent the different priorities of different language organisations, workers, and communities across Australia. So, we want the community to know why we’re asking these questions. And also, why they should answer the questions. Because ultimately, that’s why we’re asking the survey questions, because we want people to answer the questions.

Alex: Yeah, yeah, and I think that also comes through in the next part of the survey as well, which is about how languages can be better supported, which again gives a lot of, sort of co-designed ideas of different ways of support that people can then talk to and expand on, so that what comes through in your data, hopefully, is really community-led ideas of what government support or community support would look like, rather than top-down approaches.

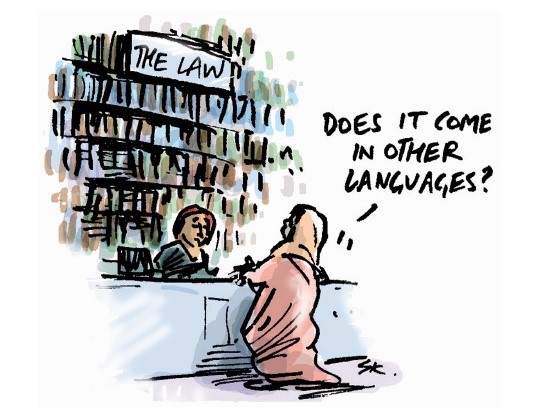

So, for example, the survey asks about forms of government funding, reform to government infrastructure, access to what the survey calls ‘spaces for languages’. I really like this idea as a sociolinguist, I really get that. Access to language materials through community support. The survey also mentions legislation about languages as a possible form of support. So this should encourage policymakers not to intuit or impose solutions, but rather to listen to the survey language respondents and what they say they need.

What I especially noticed in this part of the survey was the question about racism affecting the strength of language. Or, if you like, reducing racism as a way of supporting language renewal. I don’t think this question was asked in previous versions of the survey, right? Can you tell us what led your team to include this one?

Zoe: Yeah, so, this idea of a supported language, as I measured… as I explained before, is one of the measures in, Outcome 16 of Closing the Gap, and that we want policymakers to listen to what the language communities want and need in regards of support, because, you know, in Australia, there’s so much language diversity, it’s not a one-size-fits-all approach. Funding was something that all language communities had in common, whether it was language revitalisation they needed funding for, resources and language workers, but also languages that, one could say are in maintenance, so languages considered strong languages, that have a lot of speakers, they also need funding to make sure that their language, isn’t at risk of being lost, and that, it can stay a strong language.

So, there are other kinds of ways that a language can be supported, and if we’re talking about, kind of racism and discrimination as a way that a language isn’t supported. It was important for us to kind of ask that question, because in co-design it was clear that racism and discrimination are still massively impacting language revitalisation and strengthening efforts. The unfortunate reality of the situation of Australian languages, Indigenous languages, is that due to colonisation, Indigenous languages have been actively suppressed.

We want to make sure that respondents of the survey have the opportunity to, kind of, participate in this truth-telling. It is an optional question. We understand it can be somewhat distressing to talk about language loss and the impacts of racism and things like that, but if respondents feel comfortable to answer this question, it does give communities the opportunity to share their stories about how their language has been impacted by racism. So, yeah.

Alex: I really think that’s important, not just to inform future policy, but the act of responding itself, as you say, is a form of truth-telling, and the act of asking, and having an institute that will then combine all those responses and tell other people. That’s an act of what we might call truth-listening, which is really important in confronting the social setting of language use and renewal. This goes back then, I guess, to strength. It’s not just how many people learn a language, or how many children exist who grow up in households speaking a language. There has to be a social world in which that language is not discriminated against, and those people don’t feel discriminated against for wanting to learn that language or wanting to use it.

Now, people may get the impression that language renewal is all hardship and bad news because of a focus on ‘language loss’, in quotes, or language ‘death’, or oppression. This pervades so much of the academic and media commentary. But you and I, Zoe, we met recently in person at a fabulous Indigenous-led conference in Darwin called PULiiMA and there, there were delegates from 196 Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander languages participating. So, that’s just one indication of the enormous effort and progress in this space around Australia, and mainly progress and effort initiated by language communities themselves, rather than governments.

So in that context, it’s important, I think, that this survey also has a section about languages flourishing, the positive focus. Languages are being learnt and taught and used and revived and loved. Tell us more about the design and purpose of the ‘flourishing’ sections of the survey.

Zoe: Yeah, I just want to say that how awesome PULiiMA was, and to see all the different communities all there, and there was so much language and love and support in the room, and everyone had a story to tell about how their language was flourishing, which was so awesome to hear. A flourishing language in terms of designing a survey and asking questions about, is a language flourishing, is a tricky thing to unpack, because in co-design, we kind of heard that a flourishing language can be put down to two things, and that’s visibility and growth of a language. And so growth of a language is something that you can understand, based off the questions that we’ve already asked, in kind of the strength of a language, how many speakers, is this number more or less compared to last time, the last survey? We’re also asking questions about, ‘has this number grown?’ in case it kind of sits within the same bracket as it did in the last survey.

And visibility is, kind of the other factor, which can be misleading sometimes as well. We’re asking questions about you know, is it being used in place names, public signage, films and media. Just to name a few. But a language that is highly visible in public maybe assumed to be strong, but isn’t strong where it matters, so, being used within families and communities. So, this section is a little bit smaller, because it kind of builds on the questions in previous sections.

It will be interesting to see, kind of, the idea of a flourishing language, and we do have the opportunity for people to kind of expand on their, responses in, kind of, long form answers, so people can explain, in their own words, in detail, if they choose to, kind of, how they see their language as being flourishing,

But, yeah, for a language to be strong and flourishing, it needs to be supported, and that’s something that was very clear in co-design, and people wanting things like language legislation, and funding, and how these things can be used to support the language strength, and to allow it to flourish. So in this section, we also have, kind of, an opportunity for people to give us their top 3 language goals. So whether that’s, they want to increase the number of speakers, or they want to improve community well-being. All sorts of different language goals and the opportunity for people to put their own language goals and the supports needed to achieve those language goals. So, the people who would benefit from the data from this survey, the government, policy makers, communities, they can see what community has actually said are their priorities for their language, and what they believe is the best way to address those language goals. So, encouraging self-determination, within this survey.

Alex: And following on from that point, I have a question in a second about, sort of, how you report the information, and also data sovereignty, how communities have access to, in a self-determined way, use this resource. But I just wanted to ask one more procedural question first. So, you shared a complete draft with me, and we’ve spoken about the redrafting process, so I know the survey’s close to ready, but where are you at the team at AIATIS is up to now – and now, actually, for those listening in the future, is October 2025. Do you have an idea of when it will be released for people to answer, and who will you be asking to answer this survey?

[brief muted interruption]Zoe: Yeah, so we’ve just hit a huge milestone in the research project where we’re in the middle of our ethics application. So, we’ve kind of finished drafting the survey, and it’s getting ready for review from the Ethics Committee at AIATSIS. And hopefully, if all goes well, we’ll be able to start rolling out the survey in November [2025].

So yes, it’s been a long time coming. This survey’s been in the works for many years. I’ve only personally been working on this project for a little under 12 months, but there have been many people before me working towards this milestone.

And the people that we want to be completing this survey are what we’re calling language respondents. So we don’t necessarily want every Indigenous person in Australia to talk about their language, but rather have one response per language by a language respondent who can kind of speak on the whole situation and status of their language, and can answer questions like how many speakers speak the language. So that could be anyone from an elder to a language centre staff member, maybe a teacher or staff member at a bilingual school. We’re not defining language respondent and who can be a language respondent because we understand that that’s different, depending on the language community, and if there are thousands of speakers of a language, or very few speakers of a language. We also understand that there could be multiple people within one language group that are considered language respondents, so we’re not limiting the survey to one response per language, but that’s kind of the underlying goal that we can get as many responses from the different languages in Australia, but at least one per language.

Alex: That makes sense. So, it’s sort of at least one per speaker group, or one per language community.

Zoe: Yeah.

Alex: Yep. Yeah. Yep. And then… so the questions I foreshadowed just before, one is about the reporting. So, I noticed last time around the National Indigenous Languages Report, which came out after the last survey – so the report came out in 2020 – that incorporated this really important idea of language ecologies, and that was one of the biggest innovations of that round of the survey. And that was, I think, directed at presenting the results in a way that better contextualized what support actually looks like on the ground, rather than this very abstracted notion of each language being very distinct and sort of just recorded in government metrics, but [rather] embedding it in a sense of lots of dynamic language practices, from people who use more than one variety.

So do you want to tell us a little bit more about how you’ve understood that language ecologies idea? Because I see that comes up in a question as well, this time around in the survey, and is it in the survey because you’re hoping to use that in the framing of the report as well?

Zoe: Yeah, so the third NILS, which produced the National Indigenous Languages Report in 2020, contributed massively to increasing awareness of language ecologies, and this idea that a language doesn’t exist within a bubble. It has contextual influences, particularly when it comes to multilingualism and other languages that incorporate, are incorporated into the community. So NILS4 aims to build on this work, in collecting interconnected data about what languages are being used. Who are they being used by? In what ways? Where are they being used at schools? At the shops, in the home. Different languages, as you mentioned before, different varieties of English, so that could be Aboriginal English, for example, or Standard Australian English. It could be other Indigenous, traditional Indigenous languages, so some communities are highly multilingual and can speak many different traditional languages. Some communities may use sign languages, whether that’s traditional sign languages or new sign languages, like Black Auslan. And kind of knowing how communities use not only the language that the survey is being responded to about, but also other languages, which will help with things like interpreting and translating services, education services, all sorts of different, things that, by understanding the language ecology better and the environment that the language exists in, yeah —

Alex: That makes sense, and there you’ve mentioned a few things that I didn’t really ask you about, but I’ll just flag they’re there in the survey too, translation and interpreting services, education, government services, and more broadly, workforce participation through a particular Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander language. That’s important data to collect. But the last sort of pressing question I have for you in this podcast is not about language work but about data sovereignty. This is a really big issue in Australia, not just for this survey, but for all research, by and with Indigenous peoples, and particularly looking at older research that was done without the involvement of Indigenous people, where there’s been problems with who controls and accesses data. So, what happens to the data that AIATSIS collects through this survey?

Zoe: Yeah, so data sovereignty is obviously one of our priorities and communities fundamentally will own the data that they input into the survey. And there will be different ways that, this information will be shared or published, depending on what the respondent consents to. So, part of the survey includes this consent form, where they basically, can decide how their data will be used and shared. And so the kind of three primary ways that the data will be used is: it will be sent to the Productivity Commission for Closing the Gap data, as I mentioned before, we have been funded in order to produce data for Closing the Gap Target 16, and so the data that’s sent to the Productivity Commission will be all de-identified. And this will be all the, kind of, quantitative responses, so nothing that can kind of be identified will be sent to the Productivity Commission. And this kind of data is kind of the baseline of what people are consenting to by participating in the survey. If they don’t consent to this, then, they don’t have to do the survey, their response won’t be recorded.

And then the other kind of two ways that AIATSIS will be reporting on the data is through the NILS4 report that will be published next year [2026], and also this kind of interactive dashboard on our website. So people will be able to kind of look at some of the responses. And communities will have the option on whether this data is identified or de-identified, so some communities may wish to have their responses identifiable, and people will be able to search through and see kind of data that relates to their communities, or communities of interest, or they might choose to kind of remain anonymous and de-identified, and so these are going to be mostly quantitative responses as well.

However, we are interested in, kind of publishing these case studies in the NILS report, which will be opportunities for communities to tell their language journey in their own words. And so this is a co-opt, sorry, an opt-in co-authored chapter in the NILS report, that, yeah, language communities can not just have data, or their responses, but have the context provided, the story of their language and their data. And that was something that was really evident in co-design, that the qualitative data needs to exist alongside the quantitative data, and that’s a huge part of data sovereignty as well, like, how communities want to be able to share their data. So, we’re really excited about this kind of, co-authored case study chapter in the report, because community are excited about it as well. They want to be able to tell their story in, in their own words.

And so, that’s kind of how the data will be used and published, but, there are other ways that the community will be able to kind of access their data that they provide in the survey. So, that’s also really important to us, and we’re following the kind of definitions of Indigenous data sovereignty from the Maiam Nayri Wingara data sovereignty principles. So, making sure that, yeah, community have ownership of their data, and they can have access to it, are able to interpret it, analyse it. And this is kind of being done from the beginning of co-design all the way up to the reporting, and that, yeah, community have control over their data at all points of this process.

Alex: It sounded like just such a thoughtfully managed and thoughtfully designed survey, so thanks again, Zoe, for talking us through it, and all the best for a successful rollout. The next phase should be really interesting for you to actually get people reading and responding, and I’ll be looking out for the survey results when you publish them later in 2026. Is there anything else about the survey that you’d like to tell our listeners?

Zoe: I think that we’ve had a really, productive conversation about our survey. We’re really excited to start rolling it out, and we’re really excited for people to look out for the results as they start to be published and shared next year. So, yeah, if anybody has any questions, or would like more information, I encourage everyone to kind of check out our website and send us an email. But yeah, thank you for having me, and for letting me chat about this project. It’s been a huge part of my life for the past few months, and excited for the rest of the world to get to experience this data, which is hopefully going to have such a big impact on communities having this accurate, reliable, comprehensive national database, that can be used for, yeah, major strides in Indigenous languages in Australia.

Alex: Well, we’ll definitely put the AIATSIS website, which is AIATSIS.gov.au, in the show notes, and then when the particular survey is out for people to respond to, we’ll put that in the notes on the Language on the Move blog that embeds this interview as well. And then people will be able to, as I understand it, respond online to the survey, or over the phone, or in person, and in a written form as well. So, as that information is available, we’ll share that with this interview.

So, for now, thanks so much again, Zoe, for talking me through this survey, and thanks everyone for listening. If you enjoyed the show, please subscribe to our channel, leave a 5-star review on your podcast app of choice, and of course, please recommend the Language on the Move podcast and our partner, The New Books Network, to your students, your colleagues, your friends. Speak to you next time!

Zoe: Thank you.

]]>The conversation focuses on a study of adults with three languages ‘at play’ in their childhoods and lives today, exploring how visible racial differences from the mainstream, social power, emotions, and familial relationships continue to shape their use – or erasure – of their linguistic heritage.

Zozan’s book opens with a funny and touching account of how her own experiences as a person of “ambiguous ethnicity” shaped this research. We begin our interview on this topic. Zozan points out that the last Australian Census showed that 48.2% of the population has one or both parents born overseas. Yet, she argues, “our teachers and our education system are unprepared, perpetuating the power relations that reinforce injustice and inequality towards half of the population”.

Then we focus on what diversity feels like to her research participants and how “mixedness” or “hybridity” is not normalised, despite being common. We build on a point Zozan makes in her book, that throughout their daily lives the participants “have to position themselves because our [social and institutional] understanding of identity is narrow-mindedly focused on a single affiliation. […] While all participants are engaged in such strategic positioning, my findings emphasise that this can come at a great personal expense, something which is not sufficiently recognised by scholarly work in this field thus far.”

Dr Zozan Balci with her new book (Image credit: Zozan Balci)

We then delve into the emotions experienced and remembered by participants in relation to certain language practices in both childhood and more recent years, and the way these shape their habits of language choice and self-silencing. While negative emotional experiences have impacted on heritage language transmission and use, Zozan’s study shows how people who had distanced themselves from their heritage language – and its speakers – then changed: “it only [took] one loving person […] to reintroduce my participants to a long-lost interest in their heritage language”. We focus on this “message of hope” and then on another cause of hope, being the engaged results Zozan’s achieved when she redesigned a university classroom activity to un-teach a deficit mentality about heritage languages and identities.

Finally, we discuss Zozan and her team’s current “Say Our Name” project. This practically-oriented extension of Zozan’s research addresses one specific aspect of linguistic heritage and identity formation: the alienation experienced by people whose names are considered ‘tricky’ or ‘foreign’ in Anglo-centric contexts. The project has created practical guides now used by universities and corporations and the City of Sydney recently hosted a public premiere of the Say Our Names documentary. Soon, Zozan will be developing an iteration of the project with the University of Liverpool in the UK.

Follow Zozan Balci on LinkedIn. She’s also available for guest talks and happy to discuss via LinkedIn.

If you liked this episode, support us by subscribing to the Language on the Move Podcast on your podcast app of choice, leaving a 5-star review, and recommending the Language on the Move Podcast and our partner the New Books Network to your students, colleagues, and friends.

Transcript

ALEX: Welcome to the Language on the Move podcast, a channel on the New Books Network. I’m Alex Grey, and I’m a research fellow and senior lecturer at the University of Technology Sydney in Australia. My guest today is Dr. Zozan Balci, a colleague of mine at UTS. Zozan is an award-winning academic, a sociolinguist, and a social justice advocate. Zozan, welcome to the show.

ZOZAN: Hello, thank you for having me.

ALEX: A pleasure! Now, Zozan, you teach in the Social and Political Science program here at UTS, and I know you have a lot of teaching experience, but today we’ll focus on your sociolinguistics research. In particular, let’s talk about your new book. How exciting! It’s called Erased Voices and Unspoken Heritage: Language, identity, and belonging in the lives of cultural in-betweeners. You’ve just published it with Routledge.

The first chapter is called A Day in the Life of the Ethnically Ambiguous, and you begin by talking about your own, as you put it, “ambiguous ethnicity”. So let’s start there. Tell us about how your own life shaped this research, and then who participated in the study that you designed.

ZOZAN: Yeah, thank you so much, and yes, “ethnically ambiguous” is kind of like the joke that I always introduce myself with. So, I was born and raised in Germany to immigrant parents, so although I’m German, I look Mediterranean. And so people mistake me from being from all sorts of places. I’ve been mistaken for pretty much everything but German at this point. So, you know, I personally grew up, in my house, we spoke 3 languages, so we spoke German, Italian, and Turkish, which is essentially how my family is made up. And, you know, this has kind of resulted in a bit of a… I’m gonna call it a lifelong identity crisis, because, you know, that’s a lot of cultures in one home.

And it also has played out in language quite interestingly, and I just kind of wanted to see with my study if others struggle with the same sort of thing, other people who are in this kind of environment, and I found that they do. And so in the book. I tell the stories of four people, all who have two ancestries in addition to the country they are born in, so there’s three languages at least at play. And all are visible minorities, so they… they don’t look like the mainstream culture in their… in the country where they were born. And all struggle having so many different cultures and languages to navigate. And, you know, it’s quite interesting, in some of the cases, the parents are from vastly different parts of the world, so the kid actually looks nothing like one of their parents.

So, one example is my participant, Claire. She has a Japanese mother and a Ugandan father, and so she speaks of the struggle of looking nothing like a Japanese person, so in her words, all people ever see is that she’s black.

And so there is some really heartbreaking stories about, you know, how challenging that is, growing up in Australia when you look nothing like your mum, and…You know, it’s also hard to assert your Japanese heritage when people look at you and don’t accept that you are half Japanese, even though she strongly identifies with it, for example. So, there are a couple of participants like that.

One of my participants, Kai, is probably the one I personally relate to the most. His mother is Greek, and his father is Swedish, and he looks very Mediterranean like me. So, he talks a lot about, you know, the guilt towards his heritage community, also internalized racism, and that is something I could probably personally very much relate to. So these are the kinds of stories that are in this book.

ALEX: They’re wonderful stories because you frame them in such a clear way that connects them to research and connects them to bigger ideas than just the personal experience of each participant, but it becomes very moving. These participants clearly have a great rapport with you. When Claire talks about speaking Japanese and the impact being a visible minority and visibly not Japanese, it seems, to other people, has on her. That’s incredibly touching, but also the effect that has on her mum, and her mum’s desire to pass on heritage language to Claire.

But the opening few pages are also, I have to say, really funny and interesting. They drew me in, I wanted to keep reading. So I’ll just add that in there to encourage listeners to go out and seek more of your voice after this podcast by reading the book.

Now, in this book, your intention, in your own words, is to explain what diversity feels like, and to normalize mixedness. And you point out that this is really important, pressing, in a place like Australia, but many places where our listeners will be around the world are similar. In Australia, about half the population are what we might call second-generation migrants, with at least one parent born overseas. And so you go on to say, this book aims to have a genuine conversation about what diversity and inclusion look like.

So, tell us more about what hybridity is. This is a concept you use for the, if you like, the sort of

embodied personal diversity of people, and what it feels like for your participants, and whether hybrid identities are recognised and included.

ZOZAN: Yeah, you know, it’s actually quite interesting, because when people hear that you’re culturally quite mixed, they kind of misunderstand what it’s like. So, you know, your mind doesn’t work in nationalities or languages, right? So in the case of my study, where three cultures or languages, are at play, you know, those… these participants don’t consider that they have three identities. Like, that is not how a mind works.

So rather, you are a person who has mixed it all up. So you don’t just think in one language, unless you have to. Like, for example, right now, I’m speaking to you in English, because I have to, but, you know, when I’m just chopping my vegetables and thinking about my day, I don’t think in only English. It’s a mix, in a single sentence, I would mix. If I speak to someone who can understand another language that I speak, I would probably mix those two. Like, it’s just… but I don’t do this, like, oh, let me mix two languages. Like, I’m not consciously doing that. And the same goes for behaviours or practices.

So, the way I kind of, you know, an analogy that I think you can use here, maybe to make it easier to understand, is if you think of, you know, say you have your 3 cultures, and there are 3 liquids, and so you pour them all in a cup and make a cocktail, right? So you mix them all up. And…

ZOZAN: you know, it’s… It’s very hard, then, to tell the individual flavour of this new cocktail now, right? It’s all mixed. But, you know, that’s not something that people understand. They want… they want the three liquids, the original liquids, what is in there? And often, you know, they will tell you that you probably ruined the drink by mixing them.

Laughter

ALEX: We laugh, but your participants have really experienced words to that effect, sure.

ZOZAN: Absolutely, and so, you know, you are often forced into a position, so you are forced to pretend you’re a different drink, because it’s very hard to, you know, separate the liquids once they have been mixed, right? And, you know, now I’m also Australian, so a dash of a new liquid has been mixed into it, you know, making the whole drink more refreshing, I think.

But, you know, unfortunately, most people still have very rigid ideas about identity, including our parents, right? So my parents cannot relate to my experience at all. They are not mixed. My teachers didn’t get it at school, right? Only people like me get it. But it’s important that we all kind of start thinking a little bit about what we’re asking people to do, because, you know.

when I went to school, for example, I could only be German, so I had to leave my other languages and my behaviours at home, because, you know, of assimilation, right? You need to assimilate to everybody else.

And then in my house with my parents, you need to leave the German outside, so it’s considered disrespectful if I say I’m German, right? So my parents would hate to hear this podcast, for example. Because to them, it’s like renouncing your heritage, right? So it’s about… you need to preserve what we have given you. And so you are kind of this person who’s like, well…

I don’t see it the way… I’m not three things. This is all me, and it’s actually people trying to over-analyse what kind of nationality this behaviour is, or this language is. In your head, you’re not actually doing that. You’re just one person who is a cocktail.

ALEX: That makes a lot of sense when you explain it, but in the findings, it becomes really clear that that’s actually very hard for people to assert as an identity. As you say, with parents, with teachers, with the public at large. You call it strategic positioning, the way people have to downplay, or almost ignore, or not show their language, or not show their other aspects of their… their different heritages, and that that can come at great personal expense.

And you point out that, in fact, while a lot of the research literature may celebrate this mixedness or this hybridity, the fact that it comes at personal expense and is difficult is not really acknowledged very much.

Now in this work you’re also drawing on some really foundational theories of language and power. So it’s not just about feeling bad or feeling excluded. The way people are able to mix their heritage languages and other aspects of their heritage, and the way they’re not able to comes within a power play and that draws really on the work of Pierre Bourdieu. I won’t delve really deeply into his theory of habitus, but I’ll quote this explanation of yours, which I loved: “the habitus can be understood as a linguistic coping mechanism, which is very much shaped by the structures around us. We develop language habits, whether within the same language or in multiple languages, which secure our best position or future in a particular market.”

And then really innovatively, you link the formation of these habits to our emotional experiences, drawing on the work of another theorist, Margaret Wetherall. Please talk us through how these theories help explain the way your participants pretended, as children, not to speak their heritage languages. This is just one aspect of how these emotions have influenced their… their behaviours, but I think many of our listeners will have done the same thing as children themselves, or relate now to knowing children who do this.

ZOZAN: Yeah, absolutely, and I think, you know, you almost need to go back to basics. Like, we use language to communicate, and we communicate to connect with others. You know, it’s a social need, it’s a human need to connect, to belong to a group, because we are social animals. So that’s actually the purpose of language, right?

But we also associate language with a cultural group. So, if the cultural group is well-regarded, so is their language, and vice versa. So, for example, here in Australia, obviously, English is highly regarded. And Arabic is not, for example, right? So this is a direct link to how we perceive the people of these cultures, right? So we’re comparing the dominant mainstream Anglo-Saxon cultural group versus Arabic in an era of really strong Islamophobia, right? So language is both this tool for communication, and it’s also this… this… this symbol of… of power, really. And so if the way you try to connect, so the… whichever language, you use, but also how you present yourself, if that results in a negative experience in disconnect, in fact, or feelings of rejection or inclusion, we will absolutely try and avoid doing that again. So we will try to connect… we will always try to connect in a way that is more successful to achieve inclusion and connection, right? So this is kind of like the theory simplified.

And obviously, you feel these experiences in your body, right? You feel shame, or you feel rejection, you feel loneliness, whatever it may be. And equally, on the bright side, you can feel happiness, you can feel, you know, togetherness, whatever it is, inclusion. So, this is kind of the emotional aspect, right? You feel… because this is a human feeling, the connection and disconnect. So, I think that sometimes we take that a bit out of our study of language. And I think we just need to bring that back a little bit, because it actually explained…explains then, how this plays out with language, so language being a key aspect.

You know, if you are told off for speaking a certain language in a certain context, or you’re being made fun of for speaking it, or something bad happens to you when you speak it, maybe you’re singled out, because you can speak something that others can’t. You will resent that language, and you won’t want to speak it again, and you will habitually almost censor yourself from speaking it, because you don’t want to feel like that again, right? So that’s kind of… and you don’t necessarily consciously do that. This is very important. I don’t mean that, like, you know, a 5-year-old is able to notice that about themselves. But typically, the rejecting a language, by and large, happens the first time a child leaves the home, in the sense of going to kindergarten or preschool, or somewhere that is not within the immediate family, where there’s almost, like, you’re being introduced to the mainstream culture in some systemic way, and you are meeting the mainstream culture there as well. So, you are with children, especially if you have an immigrant background, or your parents do, you’re meeting lots of children who don’t. And so this is your first becoming aware of being different, and so, of course, if you look differently already, that’s… that’s difficult. But then also, if you speak differently, that makes it extra difficult.

And so, you know, one of the examples, from the book that I think was just, it actually, when he did say it in the interview, I did tear up, so I want to share this one. And so this was, Kai, so just as a refresher, he is half Greek, half Swedish, and he grew up here in Australia. And so, at the time that he grew up there was still a lot of, sort of, discrimination, towards Greek people. That has probably tempered down a little bit since, but at the time, it was very acute still, where he grew up. And so, in a school assembly, he must have been in primary school, so fairly young, in front of the entire school, he was asked, singled out, and say, “hey, Kai, you… you speak Greek, right? How do you say hello in Greek?”

And he said, “I don’t know”.

And so when I had this interview, we paused for a second, and I said, “but you knew. You knew how to say hello in Greek”. And he’s like, “yes, I knew”. And I said, “well, why… why do you think you said you didn’t know?” And he said, “well, because they didn’t know, so if I don’t know, then I can be like them”.

And I think that is very heartbreaking, right? Because, especially here in Australia, there’s this idea that, you know, if you speak another language, if you are multilingual, that is almost un-Australian. You’re supposed to be this monolingual English speaker, right? That’s the norm, that’s the mainstream. So if you divert from that, that’s different, but especially if you speak a language where the cultural group is not well regarded, right? That positions you as, firstly, different, but also lower.

ZOZAN: Right? And so we can understand, again, he probably didn’t realize, as a 7-year-old, or whenever this was, what he was doing, consciously, but you can see this pattern, right? That’s why I’m saying it’s more a feeling than it is rational thought. The way your language practices develop is based on how your body feels in response to you using, like, language.

ALEX: And the fact that it’s such an embodied feeling comes out in your participants, who are now in their 20s and 30s, remembering in detail a number of these instances from way back in their childhood. I mean, the example of Kai jumped out at me too, the school assembly, because in the context, it might have seemed to the teachers that they were trying to celebrate his difference, to sort of reward him for knowing extra languages, but that’s not how it came across to him, because he’d already started experiencing the negative disconnection that that language caused.

Now that’s one example of negative feelings, but your study shows quite a number of how people in your study developed very negative feelings and distanced themselves from their heritage languages, partly consciously, partly unconsciously, or perhaps as children, consciously, but not knowing what a drastic impact it would have in the future on their ability to ever pick that language up again.

But then you say, this changed, and this is in adulthood usually, changed through relationships with people who they love and admire: “It only took one loving person to reintroduce my participants to a long-lost interest in the heritage language. I believe this is a message of hope.”

Well, I believe you, Zozan, when you say that’s a message of hope, so tell us more about that hope.

ZOZAN: Yeah, I mean, and again, it’s about connection, right? So, this is really at the forefront of everything. So, you know, if there is a person that you can connect with, that will somehow encourage you to rediscover what you have lost, then it’s actually… it can be reversed. It doesn’t mean that, you know, now you’re completely like, “yay, let me start speaking my language again”, or whatever. It’s not necessarily that, but, you know, it tempers down some of that self-hatred that you perhaps have, that guilt, whatever it is, so that you can actually deal with this illusion.

ZOZAN: a little bit more rationally. And, you know, a lot of participants, also, kind of talked about how they’re psyching themselves up to actually visit the country where their parent is from, because slowly, they can, you know, get to that place where they are able to do that, where that… where, you know, the realization that actually there’s nothing wrong with my heritage, it’s just I have been socialized to think that, because the people I have been trying to connect with couldn’t connect with me on that.

And so in the book, there’s a couple of such examples. So in the example of Claire, she, she met a friend at school who also is Black, and has sort of introduced her to this world that she didn’t know, whether it’s, you know, beauty tips for actually women like her, which of course she said was a struggle with a Japanese mother who didn’t know what to do with her hair, and all of those things, so little things like that, but also just, you know, embracing some of these things that… that she couldn’t actually seem to, sort of grasp in her home or in school. We have Kai, whose grandmother, so he loves his grandmother, she hardly raised him, and she developed dementia, and she forgot how to speak English as a result, so she could only speak Greek, so she kind of remembered only that. And so he was like, “well, I want to speak to my grandma”. So now I have to actually up the Greek, because otherwise I cannot communicate with her, and that would be a huge shame”. So you know, that connection is much stronger than everything else. Like, “I want to stay connected to grandma”. In another instance, you know, we had, father and daughter having a bit of a difficult relationship, as is so common in our teenage years, you know, we struggle. But so her dad then taught her how to drive, and they spend all these long hours, driving together, and he, in fact, is a taxi driver, so he showed her all the, you know, the tricks and the, you know, the shortcuts. And, you know, all this time, almost forced time spent together, kind of reconnected them, and, you know, now she’s much more open to, “hey, can you… can you tell me how I… how I can say this in Hungarian?” Or, you know, feeling excited about maybe visiting Hungary, for example.

So these are the kinds of stories, and so this is really important, because connection can just undo some of that traumatic stuff that happens earlier. And you’re quite right, it typically happens as an adult. It’s almost when you kind of have fully formed, and you can look at it a bit more rationally, and actually realize, you know, all of these experiences, it’s not because something’s wrong with me, but rather there’s a lack of understanding, or there are prejudices around me. That doesn’t make it, you know, they are wrong, and I’m okay, kind of feeling, yeah.

ALEX: Yeah, yeah.

ALEX: And you point out that it’s really, at least in your study, really clear that it’s this relationship, or a change in a relationship, that comes first, and then prompts that return to the heritage language, or that renewed passion for spending some time speaking it, or learning it.

And there had been debate in the literature as to whether it’s, you know, that you learn the language first and that enables connections, and you say, well, at least in your study, it seems to be the other way around, so maybe we really need to think of building those relationships first to enable people to want to, or to feel comfortable embracing that heritage language.

I guess, to that end, to try and help people come to that position of, you know, “it’s not me who’s wrong, there’s this world of prejudices or exclusions that are a problem”, you give the wonderful example of you yourself changing your classroom behaviours in the university subjects you teach to try and unteach the idea that heritage languages and identities are deficits. And when you tried it, this wasn’t your study, but it’s, you know, something you were doing because your own study encouraged you to go in this direction, you got such engaged student participation as a result. Can you please tell our listeners about that?

ZOZAN: Yeah, absolutely, and so this was based on an experience I had in my schooling. So I, as I mentioned, I went to school in Germany, and it is very common in Germany still to study Latin as a foreign language throughout high school, and so I was one of those poor people who had to do that.

ALEX: So was I, and you can imagine it was not as… not as common here in Australia.

ZOZAN: I, I… oh, God. It was tough, …But obviously, I speak Italian, so to me, often it was much easier to write my notes in Italian, because it’s almost the same word, right?

ZOZAN: So it just helps me learn that easier. So just in my notebook by myself, I used to write, you know, the Latin word and then the Italian word next to it, because, you know, it obviously makes it easier. Now, my teacher then came around and looked at my notes and said, “well, you have to do this in German”, and I’m like, “well, these are just my personal notes, I can do whatever I want”. And he’s like, “no, that’s an unfair advantage, you have to do it in German’, right? So I’m like, okay, great, so it’s an… it’s a problem at all other times, and all of a sudden, it’s an unfair advantage, so I just… I was not allowed to use my language, even though that was the better way to teach me, right? Like, I mean, that was my individual need as a student, that would have helped me.

So, I know that, obviously, you know, I teach in Sydney, it’s a very diverse student cohort, we have people from all over the place, we have international students, we have students whose first language isn’t English. And I know that many of them, especially if they grew up here and they’ve had this background, this, you know, their parents from elsewhere, they might have had similar experiences to me, whether it’s, you know, either being shamed in some shape or form, or actively forbidden, right?

And so I thought, okay, let me try and see what we can do with that. And so in my class, I then kind of started off with, does anyone here speak or understand another language? And I think it’s very important to say, speak or understand, because that firstly opens up this idea that, oh, okay, maybe the language that I silenced myself in. Typically you can still very much understand it, so I can barely say anything in Turkish, but I understand it quite well. And so, that’s not because I’m not linguistically gifted, it’s because of what I’ve done with it, right? And so, they will then raise their hand, and you can kind of… “what language is that?” And, you know, interestingly, obviously, you will find you speak 10, 15 languages in a classroom of 30 people, because it’s typically quite diverse.

So then we looked at, in this particular example, we looked at a political issue that was, happening at the time. I actually don’t remember what it was now. But I said to them….

ALEX: Hong Kong. I think it was….

ZOZAN: The Hong Kong protests, maybe? This is a while ago. But you could do this with anything. Like, I mean, let’s say I want to do this on the, war in Ukraine, for example. You know, what is the reporting around that? So, importantly because the lesson was around political bias in news reporting, that’s why it’s important for this particular activity to pick a political issue, but you could pick something, obviously, much less confronting, if you want.

So I asked them to look at news reporting about this issue from the last week or so, and I said, if you can speak or read another language, or even listen to, say, a news report on video, have a look at what, around the world, the reporting on the same issue, how are different countries reporting on it, right? So we actually used these other languages. And it was so interesting, because obviously, once you have, you know, some people looking at, you know, obviously news from Australia, but then others news from around Europe, from around South America, from around Asia, you can absolutely see that the news reporting is different. The angles are different, what is being said, who is being biased, is different, right?

And so here we then, you know, this discussion was much richer than had I just said, okay, read news in English, or just from Australia, where, you know, we’re just gonna hear the same perspective. And so I’ve been trying as much as possible to always do that and allow my students to, you know, if you want to read a journal article for your paper from another from an author that didn’t write in English, please do, if that is helpful. You know what I mean? So, these are the kinds of things I try to bring into my classroom to kind of show them, “hey, this is an asset. You speaking another language is great. It opens another door to another culture, to another way of thinking and viewing the world. It’s not a bad thing. You should use it whenever you can.” And it has worked really well.

ALEX: Oh, I love it, and I love that it doesn’t put pressure on those people to then be perfect in their non-English language or languages either. The way you describe it in the book, the more people spoke, the more other students said, “oh, actually, I do understand a bit of this language”, or “oh yeah, I didn’t mention it before, but I also have these linguistic resources”, and everyone just feels more and more comfortable to bring everything to the table.

ALEX: The next question, I don’t know if we’ll edit it out or not, just depending on the time, but it does flow quite nicely from what you’ve just been discussing, so I’ll ask it, and you can answer it, and we’ll record it.

ALEX: So, Zozan, another way you’ve built on this project, which was originally your thesis, and then you’ve written in this wonderfully engaging book. You’ve then gone on since then to do a different related project that’s ended up with a documentary and a lot of practical applications. And I think listeners would love to hear about it. It’s a project called Say Our Names. You’re leading a team of researchers from various disciplines in this project, and it’s about challenging quote-unquote “tricky” or “foreign” names in Anglophone contexts. You’ve created some really practical guides for colleagues, which I’ve seen, and even directed a mini-documentary that showcases the lived experiences behind these names. It premiered a few months ago here in Sydney in collaboration with the City of Sydney Council. Can you tell us about this project in a nutshell, and what the public responses have been like now that your research is out there beyond the university?

ZOZAN: I know, the Say Our Names is a bit like the beast that cannot be contained for some reason, it’s really, blown up, but I think what made it so successful is because it is such an easy entryway into cultural competence, very much to, you know, speaking to the kinds of themes that are in the book. So as you know, my name, people find hard to pronounce. It really isn’t, but it is immediately foreign in most, in most places that I would go to. And I actually… my name is mispronounced so often that sometimes I don’t even know how to pronounce it correctly anymore. Like, I have to call my mum, reset my ear: “How do I say this again?”

And, you know, there’s obviously lots of people in Australia, around the world, who have this very same issue, right? So you have your name mispronounced, you have it not pronounced, because people are so scared to say it, it looks so wild to them, they just call you “you”, or just don’t refer to you at all. Or perhaps, they anglicize it, or they shorten it, and you know, it seems like a harmless thing to do, but actually, it’s sort of like, you know, it scratches the surface of a much bigger issue, right? So you have, again, this dominant culture, and so here in Australia, obviously, the English-speaking Anglo-Saxon culture with everybody else, right? And so English names we are totally fine with, but as soon as something is not English or not, you know, common European, it becomes a tricky thing, and it’s hard to say. And so you internalize that, as the person whose name that is, you internalize, my name is hard to say, my name is foreign.

And your name is the first thing you say to someone, right? You meet a new person, you say, “hi, my name is Zozan”. And… I mean…

ZOZAN: 90% of the time, either people will mispronounce it, or they will ask me more about it.

ZOZAN: And I tell this story, not in the documentary, but when I introduce the documentary. I tell the story about how I actually, a couple of years ago, this is quite, timely, I had podcast training, how to speak about my research in, for podcasts. The first task that we had to do in this training was explain our work, like, what kind of research are you, what is your research?

And I found… I got really stuck with that, like, I couldn’t put in writing what I do. And I’m a very chatty person, I normally have no trouble talking and, talking about myself, but for some reason, that seemed like an impossible task. I couldn’t… I had no idea how to say it. And I realized the reason why I don’t know how to say it is because I never, in a situation where people speak about their work, I never get past my name. People don’t want to hear about my name, sorry, my work, because they want to hear about my name.

So, you know, I say, hi, I’m Zozan at a networking event. And, “oh, what kind of name is it? Oh, where are you from? Oh, you know, what are your parents? Where are your parents from?” And you don’t actually get a chance to do what you came to do, which is, I would like to speak about my work, because I’d like an opportunity.

And so we realized this is quite important, and yes, of course, it’s adjacent to all of this work from the book. It’s, it’s, you know, your name is a lexical item as part of language, right? So we realized the need to… maybe this is an easy entry point to connect people. If we just show the importance of trying to get someone’s name right, how to ask, how to deal with your own discomfort of not knowing how to pronounce it and asking how to… to take off a little bit of the burden of the other person who’s continuously uncomfortable anyway, right?

And so, yeah, we, we, again, storytelling is my thing, so we, we had some focus groups, obviously where we could do a bit more, you know, what is your story, what is your experience, and also how would you like to be approached, right? This is very important. We don’t want to assume that, as researchers, you know, obviously I have my own ways and thoughts. But it was important, so we asked, and created this best practice guide that really came from community: “This is how people would like to be approached. This is what you can do”.

And then we also created this, little documentary. It’s… it’s really, really beautiful, I think, if I have to say so myself. But obviously it just shows the stories, it shows stories of what it… what the name means, because it is obviously part of your cultural heritage, how people have felt resentful towards their names, and ashamed of their names, in exactly the same way as people do with language in my book. So there were a lot of parallels.

And also what it means when people try to get it right, when there’s actually a person making an effort, because again, it’s about connection. Here’s someone who wants to connect with me, and who’s making the effort. So, of course, now I also want to make the effort, right? So it’s almost like this beautiful…

ZOZAN: Like, thank you for trying, and yes, I want to be your friend, let me help you. …

And so, yeah, and it went beyond UTS, it went citywide. I am… we have been receiving requests around Australia to come and screen it and hold a little panel. We’ve had panel discussions with people who are experts in this field. But also, I think what is important that we now brought in as well is Indigenous voices, because obviously there’s an erasure there of names and language that we also need to talk about in the Australian context. So, we’re doing a lot around that, and yeah, it’s been… it’s been the most practical application, I think, of my research so far.

ALEX: When I heard a panel talking about it, something I took away is just to be encouraged, you know, if you’re the person who’s asking, “how do you say your name?” You don’t have to get it right the first time, you don’t have to have just listened to it, and then you can immediately repeat it, because maybe it is an unusual name for you. You just have to be genuinely making an effort to learn, and to show that you want to connect, and that you want to get it right, and you want to ask the person how they want to be known. And that, I think, is just so important for people to keep in mind. It’s not a standard of immediate perfection, it’s a standard of attempting to genuinely respect and connect with people.

Before we wrap up, can you tell us what’s next for us, Zozan, and can we follow your work online, or even in person?

ZOZAN: Well, …

ZOZAN: Obviously, the book is available, you can buy it as an e-book, or obviously, if you’re really into hardback, you can do that too. Say Our Names is spreading far and wide. I’m taking it to Europe, at the end of the year. It will be, used in classrooms in the UK. I will be screening it at a conference in Paris, so there’s actually quite a bit of… because it’s obviously really relevant all around the world, right? We are more globalized, so very happy to do more screenings and introductions and panels. Obviously, a book tour is in the works … let’s see how we go with that, but, certainly around Sydney, and then perhaps also overseas. So I’m trying to spread the word, and, you know, I’m the kind of person who actually just wants to make an impact. I want to, you know, obviously it’s wonderful to do this research and dive into the literature and all of that, but, you know, I think I am quite proud of having translated it into something that is, you know, we have now in corporate offices our best practice guide on language and on names, and people are trying. And so, you know, I think that is the most rewarding thing, and that’s really something I want to keep working on.

ALEX: Thank you, and we’ll make sure we put your social media handles in the show notes. So thank you again, Zozan, and thanks for listening, everyone. If you enjoyed the show, please subscribe to our channel, leave a 5-star review on your podcast app of choice, and of course, recommend the Language on the Move podcast if you can, and our partner, The New Books Network, recommend to your students, your colleagues, your friends. Until next time!

]]>Today, our focus is not on what but who: we’re delighted to spotlight some of the newest members of the network. This post introduces recent advocacy, academic and community-building efforts from a leading barrister, a linguistics professor and a leading forensic linguist, a legal academic, a postdoctoral researcher, three postgraduate research students and our new LLIRN Intern.

Eleanor Kettle at the Cape of Good Hope after the 2025 IAFLL conference in Cape Town (Image credit: Eleanor Kettle)

And to keep sharing news from researchers, professionals, policy-makers and students concerned with problems arising when language issues and legal issues meet, we also have a new website to announce: www.lawandlanguage.org! We’re continuing to add to it. It houses this and other blogs from LLIRN members; teaching and research resources; and profiles of people and projects. Come visit!

Professor Gratien G. Atindogbé

Gratien G. Atindogbé, a Professor of African Languages and Linguistics at the University of Buea, Cameroon, has been a significant figure in the field since 1997. His academic journey includes a doctorate in African linguistics from the University of Bayreuth, Germany, in 1996. His research interests are diverse, covering descriptive linguistics, documentation of endangered languages, historical linguistics, tonology, Cameroonian Pidgin English, intercultural communication, forensic linguistics, and the sociolinguistics of French. Notably, he is a key member of the Pluridisciplinary Advances in African Multilingualism project, funded by the National Science Foundation in the US. His dedication to Higher Education management is evident, and he has authored nearly fifty publications, including articles, collective chapters, and scientific books.

Recent publications

Atindogbe, Gratien G. (2022). Digital Humanities for Sustainable Learning: Lessons from Documentary Linguistics. OASIS Commonwealth of Learning’s (COL) Open Access Repository. DOI https://doi.org/10.56059/pcf10.5128

Atindogbé, Gratien G. and Dissake, Koumassol Endurence M. (2019). Forensic Linguistics as a tool for the development of Cameroon national languages. African Study Monographs 40(1): 23- 44. https://doi.org/10.14989/243208

Dissake, Koumassol Endurence M. and Atindogbé, Gratien G. (2020). Analyzing Court Discourse in a Multilingual Setting: The Case of the Buea Court of First Instance. In Pier Paolo Di Carlo and Jeff Good (Eds.), African Multilingualisms. Lanham: Lexington Books.

Dr Edward Clay

Dr Edward Clay is currently a Research Fellow working in the Law School at the University of Birmingham, UK. His research interests focus on empirical and interdisciplinary approaches to law and language, examining the intersection between translation, law, terminology and linguistics. His research examines the effects of translation on terminology in legal discourse, and legal translation as a language contact scenario.

His PhD (2024) was an interdisciplinary project at the interface of law and language, translation, migration studies and linguistics, leading to a thesis entitled ‘Translation-induced language change in the field of migration: a multilingual corpus analysis of EU legal texts and press articles.’ This project examines the potential for migration terminology to emerge across different languages through translation in an institutional setting before becoming more widely established in general discourse. He is currently working on a research project funded by the Leverhulme Trust entitled ‘The Impact of Brexit: A Linguistic Perspective’ to investigate the changes in EU legal language since the UK’s withdrawal from the EU and the implications of any changes for the policy and lawmaking environment of the EU and the UK.

Recent publications