The conversation focuses on a study of adults with three languages ‘at play’ in their childhoods and lives today, exploring how visible racial differences from the mainstream, social power, emotions, and familial relationships continue to shape their use – or erasure – of their linguistic heritage.

Zozan’s book opens with a funny and touching account of how her own experiences as a person of “ambiguous ethnicity” shaped this research. We begin our interview on this topic. Zozan points out that the last Australian Census showed that 48.2% of the population has one or both parents born overseas. Yet, she argues, “our teachers and our education system are unprepared, perpetuating the power relations that reinforce injustice and inequality towards half of the population”.

Then we focus on what diversity feels like to her research participants and how “mixedness” or “hybridity” is not normalised, despite being common. We build on a point Zozan makes in her book, that throughout their daily lives the participants “have to position themselves because our [social and institutional] understanding of identity is narrow-mindedly focused on a single affiliation. […] While all participants are engaged in such strategic positioning, my findings emphasise that this can come at a great personal expense, something which is not sufficiently recognised by scholarly work in this field thus far.”

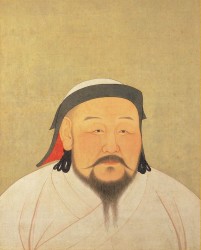

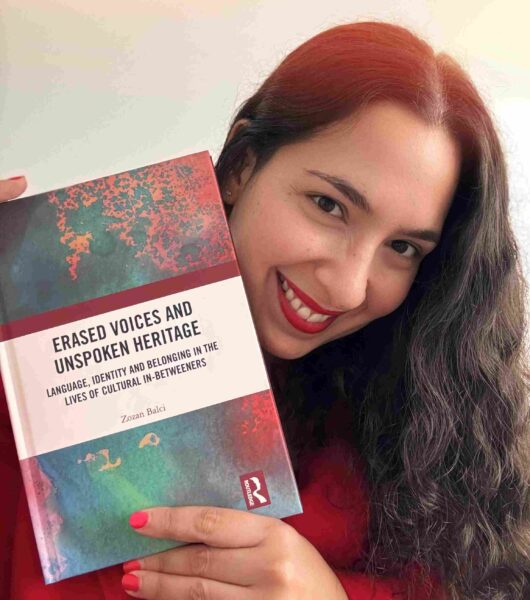

Dr Zozan Balci with her new book (Image credit: Zozan Balci)

We then delve into the emotions experienced and remembered by participants in relation to certain language practices in both childhood and more recent years, and the way these shape their habits of language choice and self-silencing. While negative emotional experiences have impacted on heritage language transmission and use, Zozan’s study shows how people who had distanced themselves from their heritage language – and its speakers – then changed: “it only [took] one loving person […] to reintroduce my participants to a long-lost interest in their heritage language”. We focus on this “message of hope” and then on another cause of hope, being the engaged results Zozan’s achieved when she redesigned a university classroom activity to un-teach a deficit mentality about heritage languages and identities.

Finally, we discuss Zozan and her team’s current “Say Our Name” project. This practically-oriented extension of Zozan’s research addresses one specific aspect of linguistic heritage and identity formation: the alienation experienced by people whose names are considered ‘tricky’ or ‘foreign’ in Anglo-centric contexts. The project has created practical guides now used by universities and corporations and the City of Sydney recently hosted a public premiere of the Say Our Names documentary. Soon, Zozan will be developing an iteration of the project with the University of Liverpool in the UK.

Follow Zozan Balci on LinkedIn. She’s also available for guest talks and happy to discuss via LinkedIn.

If you liked this episode, support us by subscribing to the Language on the Move Podcast on your podcast app of choice, leaving a 5-star review, and recommending the Language on the Move Podcast and our partner the New Books Network to your students, colleagues, and friends.

Transcript

ALEX: Welcome to the Language on the Move podcast, a channel on the New Books Network. I’m Alex Grey, and I’m a research fellow and senior lecturer at the University of Technology Sydney in Australia. My guest today is Dr. Zozan Balci, a colleague of mine at UTS. Zozan is an award-winning academic, a sociolinguist, and a social justice advocate. Zozan, welcome to the show.

ZOZAN: Hello, thank you for having me.

ALEX: A pleasure! Now, Zozan, you teach in the Social and Political Science program here at UTS, and I know you have a lot of teaching experience, but today we’ll focus on your sociolinguistics research. In particular, let’s talk about your new book. How exciting! It’s called Erased Voices and Unspoken Heritage: Language, identity, and belonging in the lives of cultural in-betweeners. You’ve just published it with Routledge.

The first chapter is called A Day in the Life of the Ethnically Ambiguous, and you begin by talking about your own, as you put it, “ambiguous ethnicity”. So let’s start there. Tell us about how your own life shaped this research, and then who participated in the study that you designed.

ZOZAN: Yeah, thank you so much, and yes, “ethnically ambiguous” is kind of like the joke that I always introduce myself with. So, I was born and raised in Germany to immigrant parents, so although I’m German, I look Mediterranean. And so people mistake me from being from all sorts of places. I’ve been mistaken for pretty much everything but German at this point. So, you know, I personally grew up, in my house, we spoke 3 languages, so we spoke German, Italian, and Turkish, which is essentially how my family is made up. And, you know, this has kind of resulted in a bit of a… I’m gonna call it a lifelong identity crisis, because, you know, that’s a lot of cultures in one home.

And it also has played out in language quite interestingly, and I just kind of wanted to see with my study if others struggle with the same sort of thing, other people who are in this kind of environment, and I found that they do. And so in the book. I tell the stories of four people, all who have two ancestries in addition to the country they are born in, so there’s three languages at least at play. And all are visible minorities, so they… they don’t look like the mainstream culture in their… in the country where they were born. And all struggle having so many different cultures and languages to navigate. And, you know, it’s quite interesting, in some of the cases, the parents are from vastly different parts of the world, so the kid actually looks nothing like one of their parents.

So, one example is my participant, Claire. She has a Japanese mother and a Ugandan father, and so she speaks of the struggle of looking nothing like a Japanese person, so in her words, all people ever see is that she’s black.

And so there is some really heartbreaking stories about, you know, how challenging that is, growing up in Australia when you look nothing like your mum, and…You know, it’s also hard to assert your Japanese heritage when people look at you and don’t accept that you are half Japanese, even though she strongly identifies with it, for example. So, there are a couple of participants like that.

One of my participants, Kai, is probably the one I personally relate to the most. His mother is Greek, and his father is Swedish, and he looks very Mediterranean like me. So, he talks a lot about, you know, the guilt towards his heritage community, also internalized racism, and that is something I could probably personally very much relate to. So these are the kinds of stories that are in this book.

ALEX: They’re wonderful stories because you frame them in such a clear way that connects them to research and connects them to bigger ideas than just the personal experience of each participant, but it becomes very moving. These participants clearly have a great rapport with you. When Claire talks about speaking Japanese and the impact being a visible minority and visibly not Japanese, it seems, to other people, has on her. That’s incredibly touching, but also the effect that has on her mum, and her mum’s desire to pass on heritage language to Claire.

But the opening few pages are also, I have to say, really funny and interesting. They drew me in, I wanted to keep reading. So I’ll just add that in there to encourage listeners to go out and seek more of your voice after this podcast by reading the book.

Now, in this book, your intention, in your own words, is to explain what diversity feels like, and to normalize mixedness. And you point out that this is really important, pressing, in a place like Australia, but many places where our listeners will be around the world are similar. In Australia, about half the population are what we might call second-generation migrants, with at least one parent born overseas. And so you go on to say, this book aims to have a genuine conversation about what diversity and inclusion look like.

So, tell us more about what hybridity is. This is a concept you use for the, if you like, the sort of

embodied personal diversity of people, and what it feels like for your participants, and whether hybrid identities are recognised and included.

ZOZAN: Yeah, you know, it’s actually quite interesting, because when people hear that you’re culturally quite mixed, they kind of misunderstand what it’s like. So, you know, your mind doesn’t work in nationalities or languages, right? So in the case of my study, where three cultures or languages, are at play, you know, those… these participants don’t consider that they have three identities. Like, that is not how a mind works.

So rather, you are a person who has mixed it all up. So you don’t just think in one language, unless you have to. Like, for example, right now, I’m speaking to you in English, because I have to, but, you know, when I’m just chopping my vegetables and thinking about my day, I don’t think in only English. It’s a mix, in a single sentence, I would mix. If I speak to someone who can understand another language that I speak, I would probably mix those two. Like, it’s just… but I don’t do this, like, oh, let me mix two languages. Like, I’m not consciously doing that. And the same goes for behaviours or practices.

So, the way I kind of, you know, an analogy that I think you can use here, maybe to make it easier to understand, is if you think of, you know, say you have your 3 cultures, and there are 3 liquids, and so you pour them all in a cup and make a cocktail, right? So you mix them all up. And…

ZOZAN: you know, it’s… It’s very hard, then, to tell the individual flavour of this new cocktail now, right? It’s all mixed. But, you know, that’s not something that people understand. They want… they want the three liquids, the original liquids, what is in there? And often, you know, they will tell you that you probably ruined the drink by mixing them.

Laughter

ALEX: We laugh, but your participants have really experienced words to that effect, sure.

ZOZAN: Absolutely, and so, you know, you are often forced into a position, so you are forced to pretend you’re a different drink, because it’s very hard to, you know, separate the liquids once they have been mixed, right? And, you know, now I’m also Australian, so a dash of a new liquid has been mixed into it, you know, making the whole drink more refreshing, I think.

But, you know, unfortunately, most people still have very rigid ideas about identity, including our parents, right? So my parents cannot relate to my experience at all. They are not mixed. My teachers didn’t get it at school, right? Only people like me get it. But it’s important that we all kind of start thinking a little bit about what we’re asking people to do, because, you know.

when I went to school, for example, I could only be German, so I had to leave my other languages and my behaviours at home, because, you know, of assimilation, right? You need to assimilate to everybody else.

And then in my house with my parents, you need to leave the German outside, so it’s considered disrespectful if I say I’m German, right? So my parents would hate to hear this podcast, for example. Because to them, it’s like renouncing your heritage, right? So it’s about… you need to preserve what we have given you. And so you are kind of this person who’s like, well…

I don’t see it the way… I’m not three things. This is all me, and it’s actually people trying to over-analyse what kind of nationality this behaviour is, or this language is. In your head, you’re not actually doing that. You’re just one person who is a cocktail.

ALEX: That makes a lot of sense when you explain it, but in the findings, it becomes really clear that that’s actually very hard for people to assert as an identity. As you say, with parents, with teachers, with the public at large. You call it strategic positioning, the way people have to downplay, or almost ignore, or not show their language, or not show their other aspects of their… their different heritages, and that that can come at great personal expense.

And you point out that, in fact, while a lot of the research literature may celebrate this mixedness or this hybridity, the fact that it comes at personal expense and is difficult is not really acknowledged very much.

Now in this work you’re also drawing on some really foundational theories of language and power. So it’s not just about feeling bad or feeling excluded. The way people are able to mix their heritage languages and other aspects of their heritage, and the way they’re not able to comes within a power play and that draws really on the work of Pierre Bourdieu. I won’t delve really deeply into his theory of habitus, but I’ll quote this explanation of yours, which I loved: “the habitus can be understood as a linguistic coping mechanism, which is very much shaped by the structures around us. We develop language habits, whether within the same language or in multiple languages, which secure our best position or future in a particular market.”

And then really innovatively, you link the formation of these habits to our emotional experiences, drawing on the work of another theorist, Margaret Wetherall. Please talk us through how these theories help explain the way your participants pretended, as children, not to speak their heritage languages. This is just one aspect of how these emotions have influenced their… their behaviours, but I think many of our listeners will have done the same thing as children themselves, or relate now to knowing children who do this.

ZOZAN: Yeah, absolutely, and I think, you know, you almost need to go back to basics. Like, we use language to communicate, and we communicate to connect with others. You know, it’s a social need, it’s a human need to connect, to belong to a group, because we are social animals. So that’s actually the purpose of language, right?

But we also associate language with a cultural group. So, if the cultural group is well-regarded, so is their language, and vice versa. So, for example, here in Australia, obviously, English is highly regarded. And Arabic is not, for example, right? So this is a direct link to how we perceive the people of these cultures, right? So we’re comparing the dominant mainstream Anglo-Saxon cultural group versus Arabic in an era of really strong Islamophobia, right? So language is both this tool for communication, and it’s also this… this… this symbol of… of power, really. And so if the way you try to connect, so the… whichever language, you use, but also how you present yourself, if that results in a negative experience in disconnect, in fact, or feelings of rejection or inclusion, we will absolutely try and avoid doing that again. So we will try to connect… we will always try to connect in a way that is more successful to achieve inclusion and connection, right? So this is kind of like the theory simplified.

And obviously, you feel these experiences in your body, right? You feel shame, or you feel rejection, you feel loneliness, whatever it may be. And equally, on the bright side, you can feel happiness, you can feel, you know, togetherness, whatever it is, inclusion. So, this is kind of the emotional aspect, right? You feel… because this is a human feeling, the connection and disconnect. So, I think that sometimes we take that a bit out of our study of language. And I think we just need to bring that back a little bit, because it actually explained…explains then, how this plays out with language, so language being a key aspect.

You know, if you are told off for speaking a certain language in a certain context, or you’re being made fun of for speaking it, or something bad happens to you when you speak it, maybe you’re singled out, because you can speak something that others can’t. You will resent that language, and you won’t want to speak it again, and you will habitually almost censor yourself from speaking it, because you don’t want to feel like that again, right? So that’s kind of… and you don’t necessarily consciously do that. This is very important. I don’t mean that, like, you know, a 5-year-old is able to notice that about themselves. But typically, the rejecting a language, by and large, happens the first time a child leaves the home, in the sense of going to kindergarten or preschool, or somewhere that is not within the immediate family, where there’s almost, like, you’re being introduced to the mainstream culture in some systemic way, and you are meeting the mainstream culture there as well. So, you are with children, especially if you have an immigrant background, or your parents do, you’re meeting lots of children who don’t. And so this is your first becoming aware of being different, and so, of course, if you look differently already, that’s… that’s difficult. But then also, if you speak differently, that makes it extra difficult.

And so, you know, one of the examples, from the book that I think was just, it actually, when he did say it in the interview, I did tear up, so I want to share this one. And so this was, Kai, so just as a refresher, he is half Greek, half Swedish, and he grew up here in Australia. And so, at the time that he grew up there was still a lot of, sort of, discrimination, towards Greek people. That has probably tempered down a little bit since, but at the time, it was very acute still, where he grew up. And so, in a school assembly, he must have been in primary school, so fairly young, in front of the entire school, he was asked, singled out, and say, “hey, Kai, you… you speak Greek, right? How do you say hello in Greek?”

And he said, “I don’t know”.

And so when I had this interview, we paused for a second, and I said, “but you knew. You knew how to say hello in Greek”. And he’s like, “yes, I knew”. And I said, “well, why… why do you think you said you didn’t know?” And he said, “well, because they didn’t know, so if I don’t know, then I can be like them”.

And I think that is very heartbreaking, right? Because, especially here in Australia, there’s this idea that, you know, if you speak another language, if you are multilingual, that is almost un-Australian. You’re supposed to be this monolingual English speaker, right? That’s the norm, that’s the mainstream. So if you divert from that, that’s different, but especially if you speak a language where the cultural group is not well regarded, right? That positions you as, firstly, different, but also lower.

ZOZAN: Right? And so we can understand, again, he probably didn’t realize, as a 7-year-old, or whenever this was, what he was doing, consciously, but you can see this pattern, right? That’s why I’m saying it’s more a feeling than it is rational thought. The way your language practices develop is based on how your body feels in response to you using, like, language.

ALEX: And the fact that it’s such an embodied feeling comes out in your participants, who are now in their 20s and 30s, remembering in detail a number of these instances from way back in their childhood. I mean, the example of Kai jumped out at me too, the school assembly, because in the context, it might have seemed to the teachers that they were trying to celebrate his difference, to sort of reward him for knowing extra languages, but that’s not how it came across to him, because he’d already started experiencing the negative disconnection that that language caused.

Now that’s one example of negative feelings, but your study shows quite a number of how people in your study developed very negative feelings and distanced themselves from their heritage languages, partly consciously, partly unconsciously, or perhaps as children, consciously, but not knowing what a drastic impact it would have in the future on their ability to ever pick that language up again.

But then you say, this changed, and this is in adulthood usually, changed through relationships with people who they love and admire: “It only took one loving person to reintroduce my participants to a long-lost interest in the heritage language. I believe this is a message of hope.”

Well, I believe you, Zozan, when you say that’s a message of hope, so tell us more about that hope.

ZOZAN: Yeah, I mean, and again, it’s about connection, right? So, this is really at the forefront of everything. So, you know, if there is a person that you can connect with, that will somehow encourage you to rediscover what you have lost, then it’s actually… it can be reversed. It doesn’t mean that, you know, now you’re completely like, “yay, let me start speaking my language again”, or whatever. It’s not necessarily that, but, you know, it tempers down some of that self-hatred that you perhaps have, that guilt, whatever it is, so that you can actually deal with this illusion.

ZOZAN: a little bit more rationally. And, you know, a lot of participants, also, kind of talked about how they’re psyching themselves up to actually visit the country where their parent is from, because slowly, they can, you know, get to that place where they are able to do that, where that… where, you know, the realization that actually there’s nothing wrong with my heritage, it’s just I have been socialized to think that, because the people I have been trying to connect with couldn’t connect with me on that.

And so in the book, there’s a couple of such examples. So in the example of Claire, she, she met a friend at school who also is Black, and has sort of introduced her to this world that she didn’t know, whether it’s, you know, beauty tips for actually women like her, which of course she said was a struggle with a Japanese mother who didn’t know what to do with her hair, and all of those things, so little things like that, but also just, you know, embracing some of these things that… that she couldn’t actually seem to, sort of grasp in her home or in school. We have Kai, whose grandmother, so he loves his grandmother, she hardly raised him, and she developed dementia, and she forgot how to speak English as a result, so she could only speak Greek, so she kind of remembered only that. And so he was like, “well, I want to speak to my grandma”. So now I have to actually up the Greek, because otherwise I cannot communicate with her, and that would be a huge shame”. So you know, that connection is much stronger than everything else. Like, “I want to stay connected to grandma”. In another instance, you know, we had, father and daughter having a bit of a difficult relationship, as is so common in our teenage years, you know, we struggle. But so her dad then taught her how to drive, and they spend all these long hours, driving together, and he, in fact, is a taxi driver, so he showed her all the, you know, the tricks and the, you know, the shortcuts. And, you know, all this time, almost forced time spent together, kind of reconnected them, and, you know, now she’s much more open to, “hey, can you… can you tell me how I… how I can say this in Hungarian?” Or, you know, feeling excited about maybe visiting Hungary, for example.

So these are the kinds of stories, and so this is really important, because connection can just undo some of that traumatic stuff that happens earlier. And you’re quite right, it typically happens as an adult. It’s almost when you kind of have fully formed, and you can look at it a bit more rationally, and actually realize, you know, all of these experiences, it’s not because something’s wrong with me, but rather there’s a lack of understanding, or there are prejudices around me. That doesn’t make it, you know, they are wrong, and I’m okay, kind of feeling, yeah.

ALEX: Yeah, yeah.

ALEX: And you point out that it’s really, at least in your study, really clear that it’s this relationship, or a change in a relationship, that comes first, and then prompts that return to the heritage language, or that renewed passion for spending some time speaking it, or learning it.

And there had been debate in the literature as to whether it’s, you know, that you learn the language first and that enables connections, and you say, well, at least in your study, it seems to be the other way around, so maybe we really need to think of building those relationships first to enable people to want to, or to feel comfortable embracing that heritage language.

I guess, to that end, to try and help people come to that position of, you know, “it’s not me who’s wrong, there’s this world of prejudices or exclusions that are a problem”, you give the wonderful example of you yourself changing your classroom behaviours in the university subjects you teach to try and unteach the idea that heritage languages and identities are deficits. And when you tried it, this wasn’t your study, but it’s, you know, something you were doing because your own study encouraged you to go in this direction, you got such engaged student participation as a result. Can you please tell our listeners about that?

ZOZAN: Yeah, absolutely, and so this was based on an experience I had in my schooling. So I, as I mentioned, I went to school in Germany, and it is very common in Germany still to study Latin as a foreign language throughout high school, and so I was one of those poor people who had to do that.

ALEX: So was I, and you can imagine it was not as… not as common here in Australia.

ZOZAN: I, I… oh, God. It was tough, …But obviously, I speak Italian, so to me, often it was much easier to write my notes in Italian, because it’s almost the same word, right?

ZOZAN: So it just helps me learn that easier. So just in my notebook by myself, I used to write, you know, the Latin word and then the Italian word next to it, because, you know, it obviously makes it easier. Now, my teacher then came around and looked at my notes and said, “well, you have to do this in German”, and I’m like, “well, these are just my personal notes, I can do whatever I want”. And he’s like, “no, that’s an unfair advantage, you have to do it in German’, right? So I’m like, okay, great, so it’s an… it’s a problem at all other times, and all of a sudden, it’s an unfair advantage, so I just… I was not allowed to use my language, even though that was the better way to teach me, right? Like, I mean, that was my individual need as a student, that would have helped me.

So, I know that, obviously, you know, I teach in Sydney, it’s a very diverse student cohort, we have people from all over the place, we have international students, we have students whose first language isn’t English. And I know that many of them, especially if they grew up here and they’ve had this background, this, you know, their parents from elsewhere, they might have had similar experiences to me, whether it’s, you know, either being shamed in some shape or form, or actively forbidden, right?

And so I thought, okay, let me try and see what we can do with that. And so in my class, I then kind of started off with, does anyone here speak or understand another language? And I think it’s very important to say, speak or understand, because that firstly opens up this idea that, oh, okay, maybe the language that I silenced myself in. Typically you can still very much understand it, so I can barely say anything in Turkish, but I understand it quite well. And so, that’s not because I’m not linguistically gifted, it’s because of what I’ve done with it, right? And so, they will then raise their hand, and you can kind of… “what language is that?” And, you know, interestingly, obviously, you will find you speak 10, 15 languages in a classroom of 30 people, because it’s typically quite diverse.

So then we looked at, in this particular example, we looked at a political issue that was, happening at the time. I actually don’t remember what it was now. But I said to them….

ALEX: Hong Kong. I think it was….

ZOZAN: The Hong Kong protests, maybe? This is a while ago. But you could do this with anything. Like, I mean, let’s say I want to do this on the, war in Ukraine, for example. You know, what is the reporting around that? So, importantly because the lesson was around political bias in news reporting, that’s why it’s important for this particular activity to pick a political issue, but you could pick something, obviously, much less confronting, if you want.

So I asked them to look at news reporting about this issue from the last week or so, and I said, if you can speak or read another language, or even listen to, say, a news report on video, have a look at what, around the world, the reporting on the same issue, how are different countries reporting on it, right? So we actually used these other languages. And it was so interesting, because obviously, once you have, you know, some people looking at, you know, obviously news from Australia, but then others news from around Europe, from around South America, from around Asia, you can absolutely see that the news reporting is different. The angles are different, what is being said, who is being biased, is different, right?

And so here we then, you know, this discussion was much richer than had I just said, okay, read news in English, or just from Australia, where, you know, we’re just gonna hear the same perspective. And so I’ve been trying as much as possible to always do that and allow my students to, you know, if you want to read a journal article for your paper from another from an author that didn’t write in English, please do, if that is helpful. You know what I mean? So, these are the kinds of things I try to bring into my classroom to kind of show them, “hey, this is an asset. You speaking another language is great. It opens another door to another culture, to another way of thinking and viewing the world. It’s not a bad thing. You should use it whenever you can.” And it has worked really well.

ALEX: Oh, I love it, and I love that it doesn’t put pressure on those people to then be perfect in their non-English language or languages either. The way you describe it in the book, the more people spoke, the more other students said, “oh, actually, I do understand a bit of this language”, or “oh yeah, I didn’t mention it before, but I also have these linguistic resources”, and everyone just feels more and more comfortable to bring everything to the table.

ALEX: The next question, I don’t know if we’ll edit it out or not, just depending on the time, but it does flow quite nicely from what you’ve just been discussing, so I’ll ask it, and you can answer it, and we’ll record it.

ALEX: So, Zozan, another way you’ve built on this project, which was originally your thesis, and then you’ve written in this wonderfully engaging book. You’ve then gone on since then to do a different related project that’s ended up with a documentary and a lot of practical applications. And I think listeners would love to hear about it. It’s a project called Say Our Names. You’re leading a team of researchers from various disciplines in this project, and it’s about challenging quote-unquote “tricky” or “foreign” names in Anglophone contexts. You’ve created some really practical guides for colleagues, which I’ve seen, and even directed a mini-documentary that showcases the lived experiences behind these names. It premiered a few months ago here in Sydney in collaboration with the City of Sydney Council. Can you tell us about this project in a nutshell, and what the public responses have been like now that your research is out there beyond the university?

ZOZAN: I know, the Say Our Names is a bit like the beast that cannot be contained for some reason, it’s really, blown up, but I think what made it so successful is because it is such an easy entryway into cultural competence, very much to, you know, speaking to the kinds of themes that are in the book. So as you know, my name, people find hard to pronounce. It really isn’t, but it is immediately foreign in most, in most places that I would go to. And I actually… my name is mispronounced so often that sometimes I don’t even know how to pronounce it correctly anymore. Like, I have to call my mum, reset my ear: “How do I say this again?”

And, you know, there’s obviously lots of people in Australia, around the world, who have this very same issue, right? So you have your name mispronounced, you have it not pronounced, because people are so scared to say it, it looks so wild to them, they just call you “you”, or just don’t refer to you at all. Or perhaps, they anglicize it, or they shorten it, and you know, it seems like a harmless thing to do, but actually, it’s sort of like, you know, it scratches the surface of a much bigger issue, right? So you have, again, this dominant culture, and so here in Australia, obviously, the English-speaking Anglo-Saxon culture with everybody else, right? And so English names we are totally fine with, but as soon as something is not English or not, you know, common European, it becomes a tricky thing, and it’s hard to say. And so you internalize that, as the person whose name that is, you internalize, my name is hard to say, my name is foreign.

And your name is the first thing you say to someone, right? You meet a new person, you say, “hi, my name is Zozan”. And… I mean…

ZOZAN: 90% of the time, either people will mispronounce it, or they will ask me more about it.

ZOZAN: And I tell this story, not in the documentary, but when I introduce the documentary. I tell the story about how I actually, a couple of years ago, this is quite, timely, I had podcast training, how to speak about my research in, for podcasts. The first task that we had to do in this training was explain our work, like, what kind of research are you, what is your research?

And I found… I got really stuck with that, like, I couldn’t put in writing what I do. And I’m a very chatty person, I normally have no trouble talking and, talking about myself, but for some reason, that seemed like an impossible task. I couldn’t… I had no idea how to say it. And I realized the reason why I don’t know how to say it is because I never, in a situation where people speak about their work, I never get past my name. People don’t want to hear about my name, sorry, my work, because they want to hear about my name.

So, you know, I say, hi, I’m Zozan at a networking event. And, “oh, what kind of name is it? Oh, where are you from? Oh, you know, what are your parents? Where are your parents from?” And you don’t actually get a chance to do what you came to do, which is, I would like to speak about my work, because I’d like an opportunity.

And so we realized this is quite important, and yes, of course, it’s adjacent to all of this work from the book. It’s, it’s, you know, your name is a lexical item as part of language, right? So we realized the need to… maybe this is an easy entry point to connect people. If we just show the importance of trying to get someone’s name right, how to ask, how to deal with your own discomfort of not knowing how to pronounce it and asking how to… to take off a little bit of the burden of the other person who’s continuously uncomfortable anyway, right?

And so, yeah, we, we, again, storytelling is my thing, so we, we had some focus groups, obviously where we could do a bit more, you know, what is your story, what is your experience, and also how would you like to be approached, right? This is very important. We don’t want to assume that, as researchers, you know, obviously I have my own ways and thoughts. But it was important, so we asked, and created this best practice guide that really came from community: “This is how people would like to be approached. This is what you can do”.

And then we also created this, little documentary. It’s… it’s really, really beautiful, I think, if I have to say so myself. But obviously it just shows the stories, it shows stories of what it… what the name means, because it is obviously part of your cultural heritage, how people have felt resentful towards their names, and ashamed of their names, in exactly the same way as people do with language in my book. So there were a lot of parallels.

And also what it means when people try to get it right, when there’s actually a person making an effort, because again, it’s about connection. Here’s someone who wants to connect with me, and who’s making the effort. So, of course, now I also want to make the effort, right? So it’s almost like this beautiful…

ZOZAN: Like, thank you for trying, and yes, I want to be your friend, let me help you. …

And so, yeah, and it went beyond UTS, it went citywide. I am… we have been receiving requests around Australia to come and screen it and hold a little panel. We’ve had panel discussions with people who are experts in this field. But also, I think what is important that we now brought in as well is Indigenous voices, because obviously there’s an erasure there of names and language that we also need to talk about in the Australian context. So, we’re doing a lot around that, and yeah, it’s been… it’s been the most practical application, I think, of my research so far.

ALEX: When I heard a panel talking about it, something I took away is just to be encouraged, you know, if you’re the person who’s asking, “how do you say your name?” You don’t have to get it right the first time, you don’t have to have just listened to it, and then you can immediately repeat it, because maybe it is an unusual name for you. You just have to be genuinely making an effort to learn, and to show that you want to connect, and that you want to get it right, and you want to ask the person how they want to be known. And that, I think, is just so important for people to keep in mind. It’s not a standard of immediate perfection, it’s a standard of attempting to genuinely respect and connect with people.

Before we wrap up, can you tell us what’s next for us, Zozan, and can we follow your work online, or even in person?

ZOZAN: Well, …

ZOZAN: Obviously, the book is available, you can buy it as an e-book, or obviously, if you’re really into hardback, you can do that too. Say Our Names is spreading far and wide. I’m taking it to Europe, at the end of the year. It will be, used in classrooms in the UK. I will be screening it at a conference in Paris, so there’s actually quite a bit of… because it’s obviously really relevant all around the world, right? We are more globalized, so very happy to do more screenings and introductions and panels. Obviously, a book tour is in the works … let’s see how we go with that, but, certainly around Sydney, and then perhaps also overseas. So I’m trying to spread the word, and, you know, I’m the kind of person who actually just wants to make an impact. I want to, you know, obviously it’s wonderful to do this research and dive into the literature and all of that, but, you know, I think I am quite proud of having translated it into something that is, you know, we have now in corporate offices our best practice guide on language and on names, and people are trying. And so, you know, I think that is the most rewarding thing, and that’s really something I want to keep working on.

ALEX: Thank you, and we’ll make sure we put your social media handles in the show notes. So thank you again, Zozan, and thanks for listening, everyone. If you enjoyed the show, please subscribe to our channel, leave a 5-star review on your podcast app of choice, and of course, recommend the Language on the Move podcast if you can, and our partner, The New Books Network, recommend to your students, your colleagues, your friends. Until next time!

]]>

One of the Nowruz traditions involves leaping over bonfires to rid oneself of pain and sorrow (Image credit: Borna News)

As people in Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, India, Iran, Iraq, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Turkey, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan prepare to celebrate Nowruz, there is a palpable sense of excitement and anticipation in the air. Nowruz, which literally means “new day” in Persian, marks the beginning of spring and the start of the new year for many peoples across the Middle East and Central Asia.

Nowruz is celebrated on the vernal equinox, typically falling on March 20 or 21, and lasts for thirteen days.

Rooted in the Zoroastrian tradition, Nowruz is a time of renewal, hope, and cultural celebration that transcends borders and unites people across the Persianate world.

Nowruz Down Under

Although in the Southern hemisphere Nowruz falls in the beginning of autumn rather than spring, still it takes on a special significance for Iranian Australians as we bring the traditions and customs of our homeland to this distant land.

The Haft-Sin table, with its seven symbolic items representing rebirth and renewal, takes centre stage in our celebrations. From sprouts symbolising growth to apples representing beauty and health, each item holds deep cultural significance and is a reminder of the values we cherish.

Spirit of Nowruz

Poetry and music fill our homes with joy and inspiration during Nowruz. Poets and writers have long captured the essence of this festival in their verses, expressing themes of renewal and spiritual growth. Music, too, plays a vital role, with traditional songs and melodies evoking a sense of nostalgia and connection to our roots.

At the heart of Nowruz is the spirit of unity and solidarity. As Iranians around the world come together to celebrate, we are reminded of the bonds that unite us as a community.

Solidarity with the people in Iran

Since the establishment of the Islamic Republic in Iran in 1979, the regime has suppressed the nation’s multifaceted and ancient culture under a theocratic dictatorship. However, for Iranians, both inside Iran and in the diaspora, Nowruz is not just a celebration of a new year. It is a celebration of our rich cultural heritage, resilience in the face of adversity, and hope for a brighter future.

So, this Nowruz, as an Australian-Iranian, deeply concerned about the future of Iran, I unite with my compatriots across the globe who embrace and celebrate Nowruz. For us, at this moment in history, Nowruz is more than just a cultural tradition. It is a unifying force and a symbol of Iranian-ness and unity, with a rich history that predates the current regime.

At the outset of Nowruz, we remember Mahsa Amini, and many other young people whose tragic deaths during the recent protests against the injustices in Iran have ignited a renewed sense of solidarity among Iranians both inside Iran and in the diaspora. Their memories remind us of the importance of standing together in the face of adversity and working towards a brighter future.

My music

This Nowruz, it’s fitting to dedicate to everyone two of my songs, that encapsulate the longing for freedom, love, and peace, “Hamseda” (Sympathizer) and “Eshghe-Bimarz” (Endless Love), which were created by a group of artists inside Iran and performed by myself.

Happy Nowruz! نوروزتان پیروز

]]>

Cover page of the first textbook in the Lift Off series

Although the Saudi government does its best to provide effective English language teaching and learning, there are widespread concerns in the country about the low level of achievement in English among Saudi students. Many researchers have tried to identify the reasons for this situation. My research focusses on the representations of culture and cultural identities in English language textbooks used at different stages in Saudi schools. As textbooks are the main teaching resource in Saudi English-as-a-foreign-language (EFL) classrooms, my research investigates the imagined communities created in these textbooks.

My MRes thesis explored how the two imagined communities of the Saudi source culture and the foreign target culture are created for Saudi students In six textbooks of the Lift Off series that is compulsory in Saudi middle schools.

Findings show nuanced and diverse representations of Saudi characters. By contrast, the representation of foreign characters is overly simplistic and involves heavy gender imbalances. While equal numbers of Saudi men and women are represented, representations of foreign women are relatively rare.

In addition, the findings show a nuanced portrayal of Saudi and Islamic cultures (i.e. the religion of Saudi learners), while representations of Western culture(s) are uniform and reductionist.

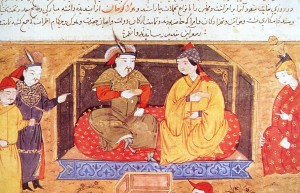

Gender segregation is represented as the norm in this Saudi EFL textbook

The compulsory EFL textbooks examined in my MRes research could be described as embracing a Saudi-centric ideological perspective, which creates a strong connection between learning English, Islam and Saudi cultural practices. At the same time, these books only show aspects of Western culture that are acceptable from an Islamic perspective, whereas aspects that are incompatible with Saudi culture and Islam are largely ignored. For example, gender segregation is represented as the norm not only in Saudi culture but also in the target cultures of English language learning.

This misrepresentation and oversimplification may impact Saudi learners and their English learning negatively by depriving them of learning about the culture and communities of the target language. Therefore, my research suggests that the administrators of EFL programs and curricula in Saudi Arabia should pay closer attention to the importance of introducing language textbooks that include rich imagined communities and characters with complex identities from both the source and the target culture to help students understand these communities and attain a high level of linguistic and intercultural competence in English.

Reference

The full text of my MRes thesis entitled “Evaluating the Representations of Identity Options and Cultural Elements in English Language Textbooks used in Saudi Arabia” is available here.

]]>

Rashid al-Din Monument in Soltaniyeh, Iran (Source: Wikipedia)

Recently, I signed a contract for a revised second edition of my 2011 book Intercultural Communication: A Critical Introduction to be published in 2017. One way in which I am planning to extend the book is to have a greater focus on cultural mediators. What are the stories, experiences and practices of people who act as brokers between languages and cultures?

In some cases, people are pushed into the role of cultural mediators out of necessity, as is the case with child cultural and linguistic mediators. Others take on the roles of cultural brokers as an act of public service. In an age when most of our own political leaders seem to be more inclined towards erecting new borders, strengthening old ones and tearing down bridges, it is instructive to consider the case of two 13th century statesmen whose friendship helped to connect east and west Asia: the Mongol Bolad and the Persian Rashid al-Din.

Rashid al-Din

Of the two, Rashid al-Din is today the better-known; as the author of the Jāme’ al-Tawārikh (“Universal History”) he is credited with having been “the first world historian” (Boyle 1971).

Rashid al-Din was born around 1250 CE into a Jewish family in Hamadān in north-west Iran. At the age of twenty-one or thirty (different accounts exist in different sources; see Kamola 2012), he converted to Islam and around the same time he entered the service of the then-ruler of Iran, the Il-Khan Abaqa (1265-81) as court physician. Under Abaqa’s grandson Il-Khan Ghazan (1295-1304) Rashid al-Din became vizier, one of the most influential roles in the state. Rashid al-Din also served Ghazan’s son and successor Öljeitü (1304-16). After Öljeitü’s death he became the victim of a court intrigue and was put to death in 1317, when he was around seventy years old.

During his long career he served his kings in many capacities: as physician, head of the royal household, military and general adviser, the mastermind of far-reaching fiscal and agricultural reforms, and, through his writing, as chief ideologue and propagandist of the Il-Khanids. In short, Rashid al-Din was a powerbroker, who did very well for himself and the realm he served:

He had become the owner of vast estates in every corner of the Il-Khan’s realm: orchards and vineyards in Azerbaijan, date-palm plantations in Southern Iraq, arable land in Western Anatolia. The administration of the state was almost a private monopoly of his family: of his fourteen sons eight were governors of provinces, including the whole of Western Iran, Georgia, Iraq and the greater part of what is now Turkey. Immense sums were at his disposal for expenditure on public and private enterprises. (Boyle 1971, p. 20)

Bolad

Thousands of miles to the east, Bolad’s career was very similar to that of Rashid al-Din: Bolad was about ten years older than Rashid al-Din and born around 1240 somewhere in Mongolia. His father was a man named Jürki, a member of the Dörben, a Mongolian tribe, who had submitted to Genghis Khan in 1204. Jürki quickly rose through the ranks of the imperial guard. In addition to his military distinction as a “Commander of a Hundred in the Personal Thousand” of Genghis Khan, he also became a ba’ruchi (“cook”) in the imperial household. While “cook” may not sound like much of a rank, in the Mongolian system this household position carried great prestige and showed close personal ties with the ruler (Allsen 1996, p. 8).

As a result of his father’s position, little Bolad was assigned to the service of Genghis Khan’s grandson Kublai Khan at age eight or nine. His education included the military arts and Chinese language and civilization. Bolad, too, forged a distinguished administrative career at the Yuan court. As he grew older, his duties and assignments included formulating court ceremonies, educating young Mongolians who entered the imperial service, and organizing the “Censorate,” the investigative arm of government. He became Head of the Bureau of Agriculture, which he helped establish; took on the role of Vice-Commissioner of Military Affairs; and headed a major anti-corruption investigation. His diverse appointments close to the centre of power at Kublai Khan’s court earned him the Chinese title chengxiang, “chancellor.”

In the spring of 1283, Bolad was appointed Kublai Khan’s ambassador to the Il-Khanids. The journey from Kublai Khan’s capital Khanbaliq (Dadu; modern Beijing) to the Il-Khan’s court in Tabriz took more than one year and Bolad and his embassy arrived in late 1284. He was supposed to return to China in 1285 but hostile forces made it impossible for a man of his rank to travel. He therefore stayed in Iran for the final twenty-eight years of his life. In addition to the role of ambassador, Bolad there assumed the role of chief advisor to the Il-Khan. During Öljeitü’s reign he became third minister and was in charge of logistics during a number of military campaigns. Active until well into his seventies, Bolad died in 1313 while he was in command of the northern garrisons.

Like Rashid al-Din, Bolad was a power broker. He distinguished himself not only at one but at two courts. Like Rashid al-Din, Bolad and his family, too, acquired significant wealth in their service to the Mongolian empire.

The context: the Yuan and Il-Khanid courts

Rashid al-Din and Bolad obviously met and became friends at the Il-Khanid court. But what was the broader context of their encounter?

After the death of Möngke Khan, a brother of Kublai Khan’s, in 1259, the unity of the Mongolian empire Genghis Khan had forged was permanently broken and the descendants of Genghis Khan fell into various succession wars. Kublai Khan held strong in Yuan China. The Il-Khanid line in Iran, founded by his brother Hülegü, formally acknowledged Kublai Khan’s sovereignty. Between these two allies, the Genghizid lines in Central Asia and Russia established various autonomous regional khanates, including the famous Golden Horde. These were at various times allied in various ways, at war with each other in various ways, and, particularly relevant here, often at war with China and Iran.

As nomadic aristocracy ruling two realms with a settled agrarian population and ancient civilizations, the Yuan in China and the Il-Khanids in Iran faced similar sets of issues: how would nomadic warriors be able to rule these complex agrarian societies?

Kublai Khan understood early that he would need Chinese support. His own Chinese language skills were not strong and he relied on interpreters in interactions with Chinese advisors (Fuchs 1946). However, he did seek out Chinese advisors and, more importantly, initiated the bilingual and bicultural education of young Mongolian courtiers such as Bolad. Bolad developed an intercultural disposition and “his frequent and active support for the recommendations of the emperor’s Han advisers indicates that he found much to admire in Chinese civilization” (Allsen 1996, p. 9).

It is unclear when and how Bolad learned Persian but on his long trip to Iran and for the first few years there, he was accompanied by an interpreter, a Syriac Christian in the employ of the Mongols, who is known in Chinese sources as Aixue (愛薛) and in Persian sources as Isa kelemchi (“Jesus the interpreter”) (Takahashi 2014, p. 43).

The actual linguistic repertoire of Aixue/Isa kelemchi is uncertain; and that is an indicator of the linguistic situation in the Il-Khanate, which was even more complex than that at the Yuan court.

The preferred languages of Il-Khan Ghazan, for instance, were Mongolian and Turkish. Additionally, he happily spoke Persian and Arabic with his courtiers. Furthermore, he reportedly understood Hindi, Kashmiri, Tibetan, Khitai, Frankish “and other languages” (Amitai-Preiss 1996, p. 27).

Rashid Al-Din wrote in Persian, Arabic and Hebrew; from his style, it can be assumed that he also had some knowledge of at least Mongolian, Turkish and Chinese (Findley 2004, p. 92).

In sum, the nomadic Mongolian conquerors, whose strengths was military, needed to integrate their culture with that of the ancient settled civilizations of China and Iran in order to maintain the empires they had gained. They did so by fostering a new class of cultural brokers. These could either be drawn from the Mongolian population and raised bilingually and biculturally, as in Bolad’s case; or recruited from the local population, as in Rashid al-Din’s case. The latter must have been far more numerous because the nomads obviously did not end up imposing their language and culture on China nor Iran.

Fusion of East and West

Bolad and Rashid al-Din ended up not “only” mediating between the nomad conquerors and the settled societies they came to rule, but their friendship is an example of the deep connections between east and west Asia that were forged during that time:

Their friendship was, without question, a crucial link in the overall exchange process, for Rashid al-Din, a man of varied intellectual interests and tremendous energy, was one of the very few individuals among the Mongols’ sedentary subjects who fully appreciated and systematically exploited the cultural possibilities created by the empire. (Allsen, 1996, p. 12)

The Jāme’ al-Tawārikh presents the culmination of their interactions. These chronicles were the first-ever attempt to write a world history and include information about the Muslim dynasties, the Indians, Jews, Franks, Chinese, Turks, and Mongols. Much of what is today known about the history of Central Asia up to the 13th century comes from the Jāme’ al-Tawārikh. This could not have been achieved without extensive collaboration, and Rashid al-Din says about Bolad that he had no rival “in knowledge of the genealogies of the Turkish tribes and the events of their history, especially that of the Mongols” (quoted from Allsen 1996, p. 13).

Inter alia, Bolad translated information from a now-lost Mongolian source, the Altan Debter (“Golden Book”). Access to the Altan Debter was forbidden to non-Mongols, and Rashid al-Din even describes how their collaboration proceeded in this case: Bolad, who, as a high-ranking Mongol, had access to the Altan Debter, would extract the desired information and then, “in the morning before taking up administrative chores,” dictate the Persian translation of the desired passages to Rashid al-Din (Allsen 1996, p. 13).

Il-Khan Hülegü and his queen, Doquz Khatun, a Syriac Christian, as depicted in a Jami’ al-Tawarikh manuscript (Source: Wikipedia)

Given the wide-ranging interests and experiences of the two men, it is not surprising that their collaboration was not restricted to history but took in many other fields, too. Principal among these is agriculture. Rashid al-Din also produced an agricultural text (Āthār va ahyā’; “Monuments and animals”), which shows considerable Chinese influence (see Allsen 1996, pp. 14ff. for details). During this time an agricultural model farm was also established in Tabriz and, on Ghazan’s orders, new strains of seeds were solicited from China and India. While the details of these cross-fertilizations have been lost in the shifting sands of time, it “can be asserted with confidence that a considerable body of information on Chinese agriculture was transmitted to Iran and that Bolad was the principal conduit” (Allsen 1996, p. 15).

The two men also collaborated in the introduction of paper money to Iran (which would have necessitated knowledge of block-printing, only available in China at the time); the translation of medicinal treatises and the implementation of aspects of Chinese medicine in the Tabriz hospital Rashid al-Din had founded; and, of course, food. Rashid al-Din, in fact, developed such a taste for the delights of Chinese cuisine that he had a Chinese chef recruited for his household.

The mountains between India and China, depicted in a Jami’ al-Tawarikh manuscript (Source: Wikipedia)

The intense friendship of Bolad and Rashid al-Din is the story of a meeting of like-minded individuals who came together across what might seem a vast chasm of cultural difference. Their wide-ranging interests and intercultural dispositions allowed them to contribute extensively – and deeply – to the fusion of Asian cultures. The results were new heights of achievement in various spheres of life, as Basil Gray, the keeper of Oriental antiquities at the British Museum between 1946 and 1969, has argued with reference to painting:

The paradox which results from a survey of the history of painting in Persia before the Mongol invasions, is that it had not yet achieved the expressive and imaginative force which was to give it its special and unique quality only after it had come in contact with Chinese drawing. This is the agent which seems to have freed the Persian genius from its subordination to the other arts of the book by a mysterious catalysis. […] The “house style” of Rashidiya [the scriptorium in Tabriz founded by Rashid al-Din] is the most thoroughgoing example of Chinese artistic penetration into Iran. In it there is not simply a question of Chinese motifs, but radical adoption of the Chinese vision. [quoted from Robinson 1980, p. 212]

That the East-West fusion enabled by the Mongolian empire was not a one-way street is best exemplified by Bolad’s name: born into a high-ranking Mongolian family, the child was given a Persian name. “Bolad” is the Mongolian version of Persian pulād (“steel”).

Allsen, T. T. (1996). Biography of a Cultural Broker, Bolad Ch’eng-Hsiang in China and Iran. In J. Raby & T. Fitzherbert (Eds.), The Court of the Il-Khans, 1290-1340 (pp. 7-22). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Amitai-Preiss, R. (1996). New Material from the Mamluk Sources for the Biography of Rashid Al-Din. In J. Raby & T. Fitzherbert (Eds.), The Court of the Il-Khans, 1290-1340 (pp. 23-37). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Boyle, J. (1971). Rashīd al-Dīn: The First World Historian Iran, 9, 19-26 DOI: 10.2307/4300435

Findley, C. V. (2004). The Turks in World History. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fuchs, W. (1946). Analecta: Zur mongolischen Uebersetzungsliteratur der Yuan-Zeit. Monumenta Serica, 11, 33-64.

Kamola, S. (2012). The Mongol Īlkhāns and Their Vizier Rashīd Al-Dīn. Iranian Studies, 45(5), 717-721. doi: 10.1080/00210862.2012.702557

Robinson, B. W. (1980). Rashid Al-Din’s World History: The Significance of the Miniatures. The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland 112(2), 212-222.

Takahashi, H. (2014). Syriac as a Vehicle for Transmission of Knowledge across Borders of Empires Horizons, 5(1), 29-52.

]]>

Churchill Square Shopping Mall, Brighton, UK (Source: Wikipedia)

In a shopping mall in the city of Brighton, UK, a tourist was arrested on terrorism charges last week for taking a selfie video. Surely, taking selfies in a shopping mall is such a part of contemporary culture that the act itself wouldn’t raise an eyebrow? What was different in the case of this tourist and this selfie? Well, the protagonist of the selfie did not speak English. According to a Daily Mail article, this is how the selfie-taking tourist aroused suspicion:

A Sussex Police spokesman said they were called by security staff after they ‘had challenged a 38-year-old London man who was filming on his mobile phone and recording in a foreign language’. The spokesman added: ‘They were concerned about his motives and he was reported to be acting strangely.’

What “foreign language” do you guess the tourist was speaking? Are you picturing tourists from France or Germany, where the holiday season has just started? Or tourists from China or Japan, who are globally stereotyped as excessive image takers? It’s unlikely that you do, and it’s unlikely that a tourist recording a selfie in any of these languages would have attracted the suspicions of a Brighton security guard.

The suspicious language – you guessed it – was Arabic. The tourist, Nasser Al-Ansari, a 38-year-old London resident and Kuwait native, was recording a Snapchat message for his friends back home. The man was released after three hours, and his side of the story is described in the Daily Mail as follows:

The former banker, who has lived in London since 2013, said: ‘It was a very horrible experience and unacceptable to happen without any specific reason or suspicion.’ ‘It is absurd. It is not something I would expect when visiting somewhere in the UK.’ He added: ‘I was very understanding and I said to them “I know it was a foreign language and my race is a factor but please be fair”. ‘I think there is a thin line between being safe and going over-the-top and this time I think they went a little over-the-top.’

According to the police, it was the “foreign language” spoken by Mr Al-Ansari that was suspicious; he himself links language and race in trying to explain why he was targeted; and some social media commentators, also raised his religion as a factor. One blogger, for instance, went with the headline “Muslim tourist takes selfie in Brighton, arrested on terrorism offences.”

We have often discussed the relationship between linguistic and racial discrimination here on Language on the Move (e.g., ‘Race to teach English;’ ‘Linguistic discrimination at work;’ ‘Shopping while bilingual can make you sick;’ or ‘Racism without racists’). But what about the relationship between language and religion when it comes to exclusion in multicultural societies characterized by linguistic and religious pluralism? How is linguistic and religious difference related to social inequality?

A recent article by the sociologist Rogers Brubaker offers a framework for thinking systematically about the ways in which linguistic and religious difference structure inequality in contemporary liberal democracies. The author identifies four domains where difference may be turned into inequality: the political and institutional domain; the economic domain; the cultural and symbolic domain; and the domain of informal social relationships.

In the political and institutional domain language is inescapable but modern liberal states are relatively neutral vis-à-vis religion. In fact, religious discrimination is widely prohibited where linguistic discrimination is seen as perfectly legitimate. Think, for instance, of citizenship testing: many liberal democracies require a language test in the national language as a precondition of naturalization while no similar religious tests currently exist in liberal democracies; and would widely be considered abhorrent.

Furthermore, in addition to explicit linguistic discrimination in favor of the national language(s), there is the inescapable fact that institutions operate exclusively in one language (or in some cases a small set of legitimate languages): this constitutes, eo ipso, a massive advantage for speakers of the institutional language and a massive disadvantage for people who do not speak the institutional language or do not speak it well.

In the economic domain similar considerations apply: proficiency in the language in which an economic activity occurs is a precondition for participation in that economic activity in a way that religion is not. Speakers of an economically powerful language enjoy an economic advantage because they do not have to invest in learning that language. Furthermore, language learning is a complex – and hence costly – undertaking that may make it difficult to acquire the kind of linguistic proficiency that has high economic value. By contrast, membership in a powerful religion is usually not as directly economically useful as language proficiency is. Furthermore, joining a powerful religion requires a smaller investment. For instance, it is much easier for a non-Christian to convert to Christianity than it is for a non-native speaker of English to acquire high-level proficiency in English.

The cultural and symbolic domain works differently. This domain includes all the discursive and symbolic processes through which respect, prestige, honor – in short symbolic value – is conferred. Here, language is less affected than religion because the “content” of a language is much thinner than that of a religion. That means that negative stereotypes about language tend to be relatively mild in comparison to negative stereotypes about religion. While many people object to the specific tenets of a particular religion, very few people object to the specific grammatical structures or means of expression of a particular language. For instance, the widespread stigmatization of Islam in contemporary media discourses simply has no equivalent in negative stereotypes about any language.

Informal social relationships also have a significant bearing on inequality, and can work through exclusion and through inclusion. Processes of social exclusion may disadvantage members of certain religions or speakers of certain languages. Examples include differential treatment of minorities on the rental market or attacks against minorities on public transport. Both members of religious minorities and speakers of minority languages are vulnerable to such “everyday exclusions.” Of course, a language may be stereotypically associated with a particular religion – as is the case with Arabic and Islam – and in such cases it is impossible to disentangle language and religion as the immediate cause of an experience such as that of Mr Al-Ansari anyways.

Informal social relationships also mediate inequality through inclusion in that social circles tend to form around shared identities; and social networks, friendship circles or marriage opportunities are often based on shared identities. Again, religion and language work differently here. Preferences for religion-internal networks is dogma in some religions while preferences for the formation of language-internal networks tend to be much weaker.

In sum, linguistic and religious difference both translate into social inequality in diverse societies but they do so in clearly distinct ways:

The major sources of religious inequality derive from religion’s thicker cultural, normative and political content, while the major sources of linguistic inequality come from the pervasiveness of language and from the increasingly and inescapably ‘languaged’ nature of political, economic and cultural life in the modern world. (Brubaker 2014, p. 23)

![]() Brubaker, R. (2014). Linguistic and Religious Pluralism: Between Difference and Inequality Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 41 (1), 3-32 DOI: 10.1080/1369183X.2014.925391

Brubaker, R. (2014). Linguistic and Religious Pluralism: Between Difference and Inequality Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 41 (1), 3-32 DOI: 10.1080/1369183X.2014.925391

‘Luxury permanent’ Mongolian yurt for sale on Alibaba

Last week when I saw in my friends’ Wechat group an advertisement for delicately made Mongolian yurts, I thought of an article I had read earlier written by Mongolian scholar Naran Bilik. In his paper about urbanized Mongolians Bilik writes:

In the Inner Mongolian region, emotional discourse and collectivism are welded together by events and inventions of the past, as well as by regular cultural activities. […] To be modern means to rebel against or modify a tradition that legitimizes the ethnicity previously taken for granted. If the gap between modernism and traditionalism, which is often translated into one between practicality and emotion, can be bridged, it is by symbolisms that overlap, touch upon, invent, or transpose reality. However, this sort of reconciliation is bound to be short-lived, situational, superficial, and manipulable (Bilik 1998, pp. 53-54).

The bridging of traditional symbols and commodification is indeed situational, relatively superficial and easily manipulable for different interests, but not necessarily short-lived. I kept visiting my friends’ Wechat group, and I found notices in traditional Mongolian script (Mongol Bichig) about looking for a sheepherder, about renting grassland, and also about selling camels. There are also advertisements for teaching how to play the Mongolian horse-head string instrument, and notices about an evening class for Mongolian costume making.

Ad for teaching how to play the Mongolian horse-head string instrument

The enthusiasm for learning a traditional musical instrument, the lack of tailors due to the increasing popularity of Mongolian costumes, and those very artistically made Mongolian furniture items and yurts confirm Naran Bilik’s argument: the gap between practicality and emotion is bridged by the reinvention or transformation of ethnic symbols.

However, in this case the reinvented symbols are also a commodity with high symbolic and material value, as Trine Brox, a scholar from Copenhagen University, explains with reference to a Tibetan market in Chengdu. In that market, Tibetans and Han Chinese meet to buy and sell ethnic minority products (Brox, 2015).

Since the mid-1980s the Chinese central government has embraced a more lenient and tolerant policy concerning religion and this has allowed a revival of Tibetan Buddhism. And Tibetan businessmen began to trade in religious commodities and set up shops in Chengdu, where they sell stone beads, ceremonial scarfs, Buddha statues, carpets, etc. to the Tibetans, Chinese and foreign tourists.

Brox speculates at the end of her article whether we are witnessing the transformation of the minzu (‘ethnicity’) categorization from a political collective identity to an economic collective identity. While she does not suggest any de-politicization of ethnic identity, she speculates that markets may be the future of ethnic culture.

Even if a market does have the potential to provide ethnic groups with a new form of ethnic collectivity, the reality will be replete with contradictions resulting from the tension between ethnic culture, on the one hand, and national and global structures, on the other hand. These tensions will leave particular Mongolian and other ethnic identities more fuzzy and shaky, but Mongolian identity will undoubtedly endure the ‘modernization’ process, as it is reinvented or reinterpreted (Bilik & Burjgin, 2003).

WeChat containing Mongolian script

Let us look at the advertisement written in traditional Mongolian script on Wechat: Mongolian script is very eye-catching because it is surrounded by other information that is predominantly in Chinese. In this case, the traditional Mongolian script is not only telling us the content of the advertisement, but also, more importantly, acting as an advertising image. In other words, the symbolic or emotional meaning of the script outweighs its practical purpose. Of course, it also demonstrates who is excluded and included, given that there is no Chinese translation provided.

The traditional scripts, the Mongolian yurts or the costumes are indeed commoditized for diverse interests, but their dynamic interaction with Mongolians’ identity and their role in both compliance with and resistance to inescapable structures should not be neglected.

So when ethnic culture and identity meet the market and go through the process of commodification, we cannot simply assume that the ethnic identity or traditional culture is undermined in the ‘modernization’ or that they are in opposition to commodification. What future research should focus on is the interaction between ethnic practices and overarching structures and influences from modernization, or globalization.

Bilik, N. (1998). Language Education, Intellectuals and Symbolic Representation: Being an Urban Mongolian in a New Configuration of Social Evolution. Nationalism and Ethnic Politics, 4(1-2), 47-67. doi: 10.1080/13537119808428528

Bilik, N., & Burjgin, J. (2003). Contemporary Mongolian Population Distribution, Migration, Cultural Change and Identity. Armonk, N.Y.: Armonk, N.Y. : M.E. Sharpe.

Brox, T. (2015). Tibetan minzu market: the intersection of ethnicity and commodity Asian Ethnicity, 1-21 DOI: 10.1080/14631369.2015.1013175

]]>

Voice of China Sydney 2015, Program Booklet

It’s a weeknight at the Sydney Town Hall, an ornate 19th century building in the city centre. Almost everyone bustling in the entryway is of Chinese extraction, except the ushers (and me). They’re all ages, and as I pour inside with them I hear Cantonese, Mandarin, Hakka, and a little English. There are posters and flyers using simplified and traditional Chinese characters alongside English text. These scripts are not in-text translations but code-switching sentences working together within each ad to sell Australian Ugg boots or New Zealand throat lozenges. The ticket I hold and the banners on stage are also multilingual. They read “The Voice of China 中国好声音 澳大利亚招募站 Season 4 Australia Audition”. The tickets were free and ‘sold out’ days before this event. It’s the final audition – in a live concert format – for the upcoming season of a popular reality TV franchise, based on ‘Voice of Holland’, and available on a subscription channel in Australia. This is the first season of ‘Voice of China’ in which ‘Overseas Chinese’ can compete for the chance to be ‘The Australian Contender’ and flown to mainland China to film the series.

In-Group, Ethnicity and Language

The Town Hall this night is clearly a space where people operate within “multi-sited transnational social fields encompassing those who leave and those who stay behind”, as Peggy Levitt and Nina Glick Schiller (2004, p. 1003) have put it. These sociologists posit that migrants may simultaneously assimilate into a host society and maintain enduring ties to those sharing their ethnic identity, “pivoting” between the two. This is a useful lens through which to regard the event. What is most interesting with ‘Voice of China’ is the use of language to extend who counts as “those who leave”. The contestants have not necessarily actually left China, many are originally from Australia. Maybe their parents, or even their grandparents, once migrated. The audition’s winner [SPOILER ALERT!] is one of the few contestants without a Chinese first name: Leon Lee, a university music student from Sydney.

As these contestants pivot towards China – particularly through their use of Putonghua-Mandarin – so too does the Chinese community pivot towards the diaspora through the vehicle of this show, both by holding these Australian auditions at all and by incorporating Cantonese and Australian English. Together, the singers, hosts, judges and audience are constructing a transnational social field that incorporates both Australia and China; Sydney is not simply a city in Australia but an Asian migration hub located in reference to Beijing. All the fans sitting around me, who might watch other ‘Voice of China’ events in virtual spaces – online and on international pay TV – while living in Sydney, demonstrate the layers of place in one geographic space.

The use of language also reveals interesting dynamics in who counts as having a shared ethnic identity. In an adjustment invisible to the audience, one contestant did not perform in his first language, the Kam-Tai language Zhuang, which is an official ethnic minority language in China. The show’s producers had said he could choose only English, Mandarin or Cantonese songs.

There is a normative equivalence of language and ethnicity being reproduced here. The way in which language features associated with Mandarin, Cantonese and Chinese minority languages “index” (Blommaert and Rampton 2011) Chinese-ness (or do not index it) is shown to be more complicated as the auditions unfurl. It is a linguistic manifestation of a recurrent normative tension over what features are identified with the Zhonghua Minzu. On one hand, Chinese minority languages and common Chinese-heritage dialects in Australia such as Hokkien and Hakka are totally absent from stage. On the other, Cantonese, although it is officially deemed a dialect not a minority language, is used by the hosts, contestants and judges. Despite Cantonese’s status, until recently it, rather than Mandarin, was the language identified as “Chinese” in Australia. Cantonese is also the Chinese language historically strongest in Hong Kong, and after all it’s a Hong Kong station (TVB) organising and presenting these auditions. Cantonese is given equivalent official status in the Town Hall show, with hosting duties meticulously shared between a Mandarin speaking man and a Cantonese-speaking woman.