NILS4 will be conducted in late 2025 to 2026 and reported upon in 2026.

There’s currently a national target in Australia about strengthening Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages by 2031. This is Target 16 in a policy framework called Closing the Gap. Zoe and I talk about how language strength can be measured in different ways and how the team have chosen to ask about language strength in this survey in ways that show clearly that the questions are informed by the voices in the co-design process.

Then we discuss the parts of the survey which ask about how languages can be better supported, for example in terms of government funding, government infrastructure, access to ‘spaces for languages’ and access to language materials, or through community support. The latest draft of the survey also mentions legislation about languages as a possible form of support. This is great; the data should encourage policy makers not to intuit or impose solutions, but rather to listen to what language authorities are saying they need. What I especially noticed in this part of the survey was the question about racism affecting the strength of a language – or reducing racism as a form of supporting languages – so I ask Zoe to tell me what led the team to include it.

We go on to discuss the enormous efforts and progress underway, and the love which many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities around Australia have for language maintenance or renewal. People may get the impression that language renewal is all hardship and bad news because a focus on language ‘loss’, ‘death’, or oppression pervades so much of the academic and media commentary. But Zoe and I both recently met in person at a fabulous, Indigenous-led conference in Darwin called PULiiMA in which delegates from 196 Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander languages participated. That’s just one indication of the enormous effort and progress around Australia, mainly initiated by language communities themselves rather than by governments. We talk about why, in this context, it’s important that this survey also has section about languages ‘flourishing’ and being learnt.

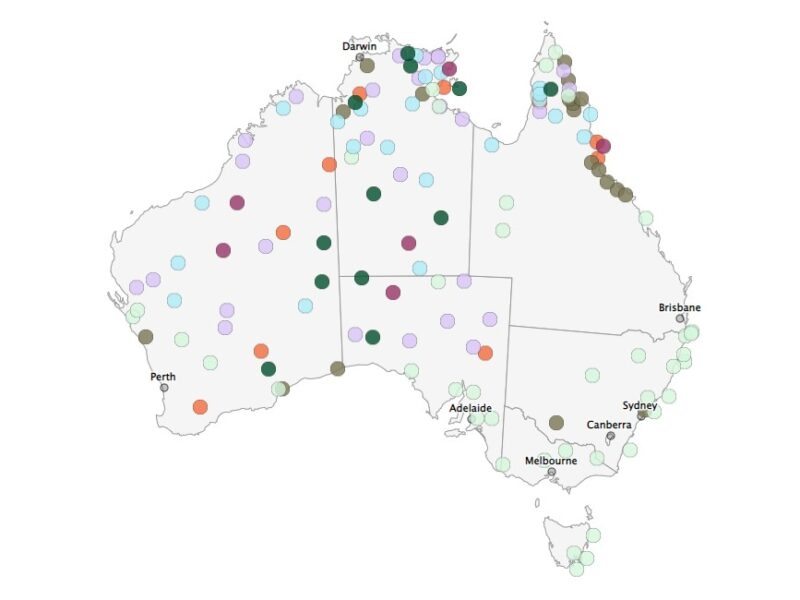

Language groups that participated in NILS3

We discuss the plans for reporting on the survey; incorporating the idea of ‘language ecologies’ was one of the biggest innovations in the National Indigenous Languages Report (2020) about the 3rd NILS and continues to inform NILS4. Finally, we talk about providing Language Respondents and communities access to the data after this survey is completed, in line with data sovereignty principles.

The survey should be available for Language Respondents to complete, on behalf of each language, in late 2025. AIATSIS will facilitate responses online, by phone, on paper and in person. If you would like to nominate a person or organisation to tell us about an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander language, please contact the team at [email protected]. Respondents will have the option of talking in greater depth about their language in case studies which AIATSIS will then include as a chapters in the report, as part of responding to calls in the co-design process to enable more access to qualitative data and data in respondents’ own words.

If you liked this episode, support us by subscribing to the Language on the Move Podcast on your podcast app of choice, leaving a 5-star review, and recommending the Language on the Move Podcast and our partner the New Books Network to your students, colleagues, and friends.

Transcript

Alex: Welcome to the Language on the Move Podcast, a channel on the New Books Network.

My name is Alex Grey, and I’m a research fellow and senior lecturer at the University of Technology in Sydney in Australia. This university stands on what has long been unceded land of the Gadi people, so I’ll just acknowledge, in the way that we do often these days in Australia, where we are. Ngyini ngalawa-ngun, mari budjari Gadi-nura-da and I’d really like to thank

Ngarigo woman, Professor Jaky Troy, who, in her professional work as a linguist, is an expert on the Sydney Language, and has helped develop that particular acknowledgement.

My guest today is Zoe Avery, a Worimi woman and a research officer at the Centre for Australian Languages. That centre is part of the Australian Institute for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, which we’ll call AIATSIS. Zoe, welcome to the show!

Zoe: Thank you! I’m really excited to be here and talking about my work that I’m doing at AIATSIS.

Alex: Yeah, so in this work at AIATSIS, you’re one of the people involved in preparing the upcoming National Indigenous Languages Survey. This will be the fourth National Indigenous Languages Survey in Australia. The first one came out now over 20 years ago, in 2005.

This time around, you and your team have made some really important changes to the survey design through the co-design process. Let’s talk about that. Can you tell us, please, what is the National Indigenous Languages Survey, what’s it used for, and how this fourth iteration was co-designed?

Zoe: Yeah, so, the National Indigenous Languages Surveys, or I’ll be calling it NILS throughout the podcast, they’re used to report the status and situation of Indigenous languages in Australia, as you mentioned. This is the fourth one. The first one was done all the way back in 2004 and, the third NILS was done about 6 years ago, in 2019. So it’s been a while, and it’s kind of just to show the progress of how, languages in Australia are being spoken and used, and I suppose the strength of the languages, which we’ll kind of go into a bit more detail. But the data is really important, because it can be used by the government to develop, appropriate language revitalisation programs or understand the areas that require the most support, but it can also be used by communities, which is really important as well.

And so, NILS4 has been a little bit different from the start compared to previous NILS, because the government has asked us to run this survey in order to measure Target 16 of Closing the Gap, which is that by 2031, languages, sorry, by 2031, there is a sustained increase in the number and strength of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages being spoken.

So, the scope for this project is much bigger than the past NILS, and AIATSIS has really prioritised Indigenous leadership in the design, and will be continuing to prioritise Indigenous voices in the rollout and reporting of the results of the survey.

So, because this is a national-level database, and we want to make sure as many languages as possible are represented, including previously under-recognized and under-reported languages, including sign languages, new languages, dialects. It’s really important that we have Indigenous voices, prioritized throughout this entire research process. And we want to make sure that the questions that are being asked in the survey are questions that the community want answers to, whether or not to advocate, to the government that these are the areas that need the most support, the most funding, or whether or not the community want that data for themselves to help develop, appropriate, culturally safe programs.

So what we did is we had this big co-design process, this year to design the survey. We had 16 co-design workshops with Indigenous language stakeholders across Australia, and this was, these workshops were facilitated by co-design specialists Yamagigu Consulting. We had, in total, about 150 people participate in the co-design process, and of these 150 people, about 107 of these were Indigenous. And so these Indigenous language stakeholders included elders, language centre staff members, teachers, interpreters, sign language users, language workers, government stakeholders, all sorts of different people that have a stake in Indigenous languages, for whatever reason. And we had 8 on-country workshops, which were held in cities around Australia, and 8 online workshops as well, which helps make it easier for, people that kind of came from different places, and weren’t able to come to an in-person workshop.

Alex: That’s a huge… sorry, just congratulations, that sounds like it’s been a huge undertaking. So many people, so many, so many workshops, well done.

Zoe: Yeah, it has been huge, and we’ve had so many different people from a variety of different language contexts, participate as well. So, the diversity of language experiences that were kind of showcased at these workshops was immense and has had a huge impact on drafting the survey, which is obviously the whole point of the workshops, but yeah … We took all the insights from the co-design workshops, we analysed them, thematically coded everything, and started incorporating everything into the survey. And then we went back to the people who participated in the co-design workshops and held these validation workshops so we could show them the draft of the survey, show them how we had planned on incorporating all of their insights, you know, that we weren’t just doing it for the sake of ticking a box to say, yes, we’ve had Indigenous engagement, but we were actually really wanting to have Indigenous input from the start, and right until the end of the project. And we had really good feedback from the validation workshops, and it is, you know, not just a massive task running these workshops, but also, making sure that everybody’s listened to, and sometimes they were kind of contrasting views about how things should be done, and yeah, we wanted to make sure that we had as much of a balance as possible.

We also consulted with the Languages Policy Partnership, which are kind of key workers in Indigenous languages policy and, advocacy. They’re kind of leaders in the Closing the Gap Target 16 that I was just talking about, so their input and advice has been really important to us, as have consultations with the Australian Bureau of Statistics and the Mayi Kuwayu Study of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Wellbeing. So yeah, there’s been a lot of input, and we’re really excited that we’re at the point now where we’re finishing the survey! Dotting all the I’s, crossing all the T’s and getting ready to start rollout soon.

Alex: Yeah, well, I mean, one would hope good input, good output! You know, such a huge process of designing it. You should get really well-targeted, really informative, useful results.

And you’ve mentioned a few things there that I’ll just explain for listeners, because not all our listeners will be familiar with the Australian context. It’s coming through that there’s enormous diversity of Indigenous peoples and languages in Australia, so to explain a little bit, because we won’t go into this in much detail in this interview, Zoe’s mentioned new languages like, contact languages, Aboriginal Englishes, Creoles, like Yumplatok, which comes from the place called the Torres Strait. If you’re not familiar with Australia, that area is between Australia, the Australian mainland, and Papua New Guinea, in the northeast. And then there’s an enormous diversity of what are sometimes called traditional languages across Australia, both on the mainland and the Tiwi Islands as well. So we have a lot of Aboriginal language diversity, and then in addition, Torres Strait Islander languages, and then in addition, new or contact varieties.

Zoe: Sign languages.

Alex: And sign… of course, yes, and sign languages. Thank you, Zoe. And then you’ve mentioned Target 16. So we have in Australia a policy framework called Closing the Gap. For the first time ever, the current Closing the Gap framework includes a target on language strength.

But as the survey goes in to, language strength can be measured in different ways. So how have you chosen to ask about language strength in this survey, and why have you chosen these ways of asking?

Zoe: Yeah, so, along with, kind of, Target 16 of Closing the Gap, there’s an Outcome 16, which is that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures and languages are strong, supported, and flourishing. So it’s important for us in the survey to, kind of, address those kind of buzzwords, strong, supported, and flourishing. But it is very clear, from co-design, that the widely used measures of language strength don’t necessarily always apply to Australian Indigenous languages. So these kind of widely used and recognised measures of how many speakers of a language are there, and is the language still being learned by children as a first language? These are not the only ways of measuring language strength, and we really wanted to make sure that we kind of redefined language strength in the survey based off Indigenous worldviews. So, language is independent [interdependent] with things like community, identity, country, ceremony, and self-determination.

How do we incorporate that into the survey? So we’re still going to be asking questions, like, how many speakers of the language are there? What age are the people who are speaking the language, but we’re also going to be asking questions on how many people understand the language, because people may not be able to speak a language due to disability, cultural protocol reasons, or due to revitalisation, for example. But they can still understand the language, and that can still be an indication of language strength. We’re also asking questions about how and where it’s used. So, do people use the language while practicing cultural activities, in ceremony, in storytelling, in writing, just to name a few? We know that Indigenous languages are so strongly entangled with culture and country, and it’s difficult to measure the strength of culture and country. But we can acknowledge the interdependencies of language, culture, and country, and by asking these kinds of questions, we can get some culturally appropriate and community-led ways of defining language strength.

Alex: And that’s just going to be so useful for, then, the raft of policies that one hopes will follow not just the survey, but follow the Target 16, and even once we get to 2031, will continue in the wake of, you know, supporting that revitalisation.

Zoe: Yeah, absolutely, and I think that, another thing that we heard from co-design, but just also from Indigenous people, in research and advocacy, that language is such a huge part of culture and identity, that by, you know, developing these programs and policies to help address, language strength, all the other Closing the Gap targets, like health and justice and education, those outcomes will all be improved as well.

Alex: Yeah, I guess that’s why, in the policy speak, language is part of one of the priority response areas for the Closing the Gap. And I noticed this round of the survey in particular is different from what I’ve seen in the earlier NILS in the way it asks questions, which also appears to reflect the co-design. So, for example, these questions about language strength, they start with the phrase, ‘we heard that’ and then a particular kind of way of thinking about strength. And then another way of thinking about strength might be presented in the next question: ‘We also heard that…’. So on, so on. So, is this so people trust the survey more, or are you conscious of phrasing the survey questions really differently compared to, say, the 2019 version of the survey?

Zoe: Yeah, absolutely we want people to trust the survey, and understand that we respect each individual response. Like, as much as it’s true, we’re a government agency, and we’ve been asked to do this to get data for Closing the Gap, we want language communities to also be able to use this data for their own self-determination, and we want to try and break down these barriers for communities and reduce the burden as much as possible. So, making sure that the survey was phrased in accessible language, and the questions were as consistent as possible.

But yeah, we wanted to make sure that we were implementing insights from co-design, but making it clear in the survey that we didn’t just kind of come up with these questions out of nowhere, that these were co-designed with community and represent the different priorities of different language organisations, workers, and communities across Australia. So, we want the community to know why we’re asking these questions. And also, why they should answer the questions. Because ultimately, that’s why we’re asking the survey questions, because we want people to answer the questions.

Alex: Yeah, yeah, and I think that also comes through in the next part of the survey as well, which is about how languages can be better supported, which again gives a lot of, sort of co-designed ideas of different ways of support that people can then talk to and expand on, so that what comes through in your data, hopefully, is really community-led ideas of what government support or community support would look like, rather than top-down approaches.

So, for example, the survey asks about forms of government funding, reform to government infrastructure, access to what the survey calls ‘spaces for languages’. I really like this idea as a sociolinguist, I really get that. Access to language materials through community support. The survey also mentions legislation about languages as a possible form of support. So this should encourage policymakers not to intuit or impose solutions, but rather to listen to the survey language respondents and what they say they need.

What I especially noticed in this part of the survey was the question about racism affecting the strength of language. Or, if you like, reducing racism as a way of supporting language renewal. I don’t think this question was asked in previous versions of the survey, right? Can you tell us what led your team to include this one?

Zoe: Yeah, so, this idea of a supported language, as I measured… as I explained before, is one of the measures in, Outcome 16 of Closing the Gap, and that we want policymakers to listen to what the language communities want and need in regards of support, because, you know, in Australia, there’s so much language diversity, it’s not a one-size-fits-all approach. Funding was something that all language communities had in common, whether it was language revitalisation they needed funding for, resources and language workers, but also languages that, one could say are in maintenance, so languages considered strong languages, that have a lot of speakers, they also need funding to make sure that their language, isn’t at risk of being lost, and that, it can stay a strong language.

So, there are other kinds of ways that a language can be supported, and if we’re talking about, kind of racism and discrimination as a way that a language isn’t supported. It was important for us to kind of ask that question, because in co-design it was clear that racism and discrimination are still massively impacting language revitalisation and strengthening efforts. The unfortunate reality of the situation of Australian languages, Indigenous languages, is that due to colonisation, Indigenous languages have been actively suppressed.

We want to make sure that respondents of the survey have the opportunity to, kind of, participate in this truth-telling. It is an optional question. We understand it can be somewhat distressing to talk about language loss and the impacts of racism and things like that, but if respondents feel comfortable to answer this question, it does give communities the opportunity to share their stories about how their language has been impacted by racism. So, yeah.

Alex: I really think that’s important, not just to inform future policy, but the act of responding itself, as you say, is a form of truth-telling, and the act of asking, and having an institute that will then combine all those responses and tell other people. That’s an act of what we might call truth-listening, which is really important in confronting the social setting of language use and renewal. This goes back then, I guess, to strength. It’s not just how many people learn a language, or how many children exist who grow up in households speaking a language. There has to be a social world in which that language is not discriminated against, and those people don’t feel discriminated against for wanting to learn that language or wanting to use it.

Now, people may get the impression that language renewal is all hardship and bad news because of a focus on ‘language loss’, in quotes, or language ‘death’, or oppression. This pervades so much of the academic and media commentary. But you and I, Zoe, we met recently in person at a fabulous Indigenous-led conference in Darwin called PULiiMA and there, there were delegates from 196 Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander languages participating. So, that’s just one indication of the enormous effort and progress in this space around Australia, and mainly progress and effort initiated by language communities themselves, rather than governments.

So in that context, it’s important, I think, that this survey also has a section about languages flourishing, the positive focus. Languages are being learnt and taught and used and revived and loved. Tell us more about the design and purpose of the ‘flourishing’ sections of the survey.

Zoe: Yeah, I just want to say that how awesome PULiiMA was, and to see all the different communities all there, and there was so much language and love and support in the room, and everyone had a story to tell about how their language was flourishing, which was so awesome to hear. A flourishing language in terms of designing a survey and asking questions about, is a language flourishing, is a tricky thing to unpack, because in co-design, we kind of heard that a flourishing language can be put down to two things, and that’s visibility and growth of a language. And so growth of a language is something that you can understand, based off the questions that we’ve already asked, in kind of the strength of a language, how many speakers, is this number more or less compared to last time, the last survey? We’re also asking questions about, ‘has this number grown?’ in case it kind of sits within the same bracket as it did in the last survey.

And visibility is, kind of the other factor, which can be misleading sometimes as well. We’re asking questions about you know, is it being used in place names, public signage, films and media. Just to name a few. But a language that is highly visible in public maybe assumed to be strong, but isn’t strong where it matters, so, being used within families and communities. So, this section is a little bit smaller, because it kind of builds on the questions in previous sections.

It will be interesting to see, kind of, the idea of a flourishing language, and we do have the opportunity for people to kind of expand on their, responses in, kind of, long form answers, so people can explain, in their own words, in detail, if they choose to, kind of, how they see their language as being flourishing,

But, yeah, for a language to be strong and flourishing, it needs to be supported, and that’s something that was very clear in co-design, and people wanting things like language legislation, and funding, and how these things can be used to support the language strength, and to allow it to flourish. So in this section, we also have, kind of, an opportunity for people to give us their top 3 language goals. So whether that’s, they want to increase the number of speakers, or they want to improve community well-being. All sorts of different language goals and the opportunity for people to put their own language goals and the supports needed to achieve those language goals. So, the people who would benefit from the data from this survey, the government, policy makers, communities, they can see what community has actually said are their priorities for their language, and what they believe is the best way to address those language goals. So, encouraging self-determination, within this survey.

Alex: And following on from that point, I have a question in a second about, sort of, how you report the information, and also data sovereignty, how communities have access to, in a self-determined way, use this resource. But I just wanted to ask one more procedural question first. So, you shared a complete draft with me, and we’ve spoken about the redrafting process, so I know the survey’s close to ready, but where are you at the team at AIATIS is up to now – and now, actually, for those listening in the future, is October 2025. Do you have an idea of when it will be released for people to answer, and who will you be asking to answer this survey?

[brief muted interruption]Zoe: Yeah, so we’ve just hit a huge milestone in the research project where we’re in the middle of our ethics application. So, we’ve kind of finished drafting the survey, and it’s getting ready for review from the Ethics Committee at AIATSIS. And hopefully, if all goes well, we’ll be able to start rolling out the survey in November [2025].

So yes, it’s been a long time coming. This survey’s been in the works for many years. I’ve only personally been working on this project for a little under 12 months, but there have been many people before me working towards this milestone.

And the people that we want to be completing this survey are what we’re calling language respondents. So we don’t necessarily want every Indigenous person in Australia to talk about their language, but rather have one response per language by a language respondent who can kind of speak on the whole situation and status of their language, and can answer questions like how many speakers speak the language. So that could be anyone from an elder to a language centre staff member, maybe a teacher or staff member at a bilingual school. We’re not defining language respondent and who can be a language respondent because we understand that that’s different, depending on the language community, and if there are thousands of speakers of a language, or very few speakers of a language. We also understand that there could be multiple people within one language group that are considered language respondents, so we’re not limiting the survey to one response per language, but that’s kind of the underlying goal that we can get as many responses from the different languages in Australia, but at least one per language.

Alex: That makes sense. So, it’s sort of at least one per speaker group, or one per language community.

Zoe: Yeah.

Alex: Yep. Yeah. Yep. And then… so the questions I foreshadowed just before, one is about the reporting. So, I noticed last time around the National Indigenous Languages Report, which came out after the last survey – so the report came out in 2020 – that incorporated this really important idea of language ecologies, and that was one of the biggest innovations of that round of the survey. And that was, I think, directed at presenting the results in a way that better contextualized what support actually looks like on the ground, rather than this very abstracted notion of each language being very distinct and sort of just recorded in government metrics, but [rather] embedding it in a sense of lots of dynamic language practices, from people who use more than one variety.

So do you want to tell us a little bit more about how you’ve understood that language ecologies idea? Because I see that comes up in a question as well, this time around in the survey, and is it in the survey because you’re hoping to use that in the framing of the report as well?

Zoe: Yeah, so the third NILS, which produced the National Indigenous Languages Report in 2020, contributed massively to increasing awareness of language ecologies, and this idea that a language doesn’t exist within a bubble. It has contextual influences, particularly when it comes to multilingualism and other languages that incorporate, are incorporated into the community. So NILS4 aims to build on this work, in collecting interconnected data about what languages are being used. Who are they being used by? In what ways? Where are they being used at schools? At the shops, in the home. Different languages, as you mentioned before, different varieties of English, so that could be Aboriginal English, for example, or Standard Australian English. It could be other Indigenous, traditional Indigenous languages, so some communities are highly multilingual and can speak many different traditional languages. Some communities may use sign languages, whether that’s traditional sign languages or new sign languages, like Black Auslan. And kind of knowing how communities use not only the language that the survey is being responded to about, but also other languages, which will help with things like interpreting and translating services, education services, all sorts of different, things that, by understanding the language ecology better and the environment that the language exists in, yeah —

Alex: That makes sense, and there you’ve mentioned a few things that I didn’t really ask you about, but I’ll just flag they’re there in the survey too, translation and interpreting services, education, government services, and more broadly, workforce participation through a particular Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander language. That’s important data to collect. But the last sort of pressing question I have for you in this podcast is not about language work but about data sovereignty. This is a really big issue in Australia, not just for this survey, but for all research, by and with Indigenous peoples, and particularly looking at older research that was done without the involvement of Indigenous people, where there’s been problems with who controls and accesses data. So, what happens to the data that AIATSIS collects through this survey?

Zoe: Yeah, so data sovereignty is obviously one of our priorities and communities fundamentally will own the data that they input into the survey. And there will be different ways that, this information will be shared or published, depending on what the respondent consents to. So, part of the survey includes this consent form, where they basically, can decide how their data will be used and shared. And so the kind of three primary ways that the data will be used is: it will be sent to the Productivity Commission for Closing the Gap data, as I mentioned before, we have been funded in order to produce data for Closing the Gap Target 16, and so the data that’s sent to the Productivity Commission will be all de-identified. And this will be all the, kind of, quantitative responses, so nothing that can kind of be identified will be sent to the Productivity Commission. And this kind of data is kind of the baseline of what people are consenting to by participating in the survey. If they don’t consent to this, then, they don’t have to do the survey, their response won’t be recorded.

And then the other kind of two ways that AIATSIS will be reporting on the data is through the NILS4 report that will be published next year [2026], and also this kind of interactive dashboard on our website. So people will be able to kind of look at some of the responses. And communities will have the option on whether this data is identified or de-identified, so some communities may wish to have their responses identifiable, and people will be able to search through and see kind of data that relates to their communities, or communities of interest, or they might choose to kind of remain anonymous and de-identified, and so these are going to be mostly quantitative responses as well.

However, we are interested in, kind of publishing these case studies in the NILS report, which will be opportunities for communities to tell their language journey in their own words. And so this is a co-opt, sorry, an opt-in co-authored chapter in the NILS report, that, yeah, language communities can not just have data, or their responses, but have the context provided, the story of their language and their data. And that was something that was really evident in co-design, that the qualitative data needs to exist alongside the quantitative data, and that’s a huge part of data sovereignty as well, like, how communities want to be able to share their data. So, we’re really excited about this kind of, co-authored case study chapter in the report, because community are excited about it as well. They want to be able to tell their story in, in their own words.

And so, that’s kind of how the data will be used and published, but, there are other ways that the community will be able to kind of access their data that they provide in the survey. So, that’s also really important to us, and we’re following the kind of definitions of Indigenous data sovereignty from the Maiam Nayri Wingara data sovereignty principles. So, making sure that, yeah, community have ownership of their data, and they can have access to it, are able to interpret it, analyse it. And this is kind of being done from the beginning of co-design all the way up to the reporting, and that, yeah, community have control over their data at all points of this process.

Alex: It sounded like just such a thoughtfully managed and thoughtfully designed survey, so thanks again, Zoe, for talking us through it, and all the best for a successful rollout. The next phase should be really interesting for you to actually get people reading and responding, and I’ll be looking out for the survey results when you publish them later in 2026. Is there anything else about the survey that you’d like to tell our listeners?

Zoe: I think that we’ve had a really, productive conversation about our survey. We’re really excited to start rolling it out, and we’re really excited for people to look out for the results as they start to be published and shared next year. So, yeah, if anybody has any questions, or would like more information, I encourage everyone to kind of check out our website and send us an email. But yeah, thank you for having me, and for letting me chat about this project. It’s been a huge part of my life for the past few months, and excited for the rest of the world to get to experience this data, which is hopefully going to have such a big impact on communities having this accurate, reliable, comprehensive national database, that can be used for, yeah, major strides in Indigenous languages in Australia.

Alex: Well, we’ll definitely put the AIATSIS website, which is AIATSIS.gov.au, in the show notes, and then when the particular survey is out for people to respond to, we’ll put that in the notes on the Language on the Move blog that embeds this interview as well. And then people will be able to, as I understand it, respond online to the survey, or over the phone, or in person, and in a written form as well. So, as that information is available, we’ll share that with this interview.

So, for now, thanks so much again, Zoe, for talking me through this survey, and thanks everyone for listening. If you enjoyed the show, please subscribe to our channel, leave a 5-star review on your podcast app of choice, and of course, please recommend the Language on the Move podcast and our partner, The New Books Network, to your students, your colleagues, your friends. Speak to you next time!

Zoe: Thank you.

]]>

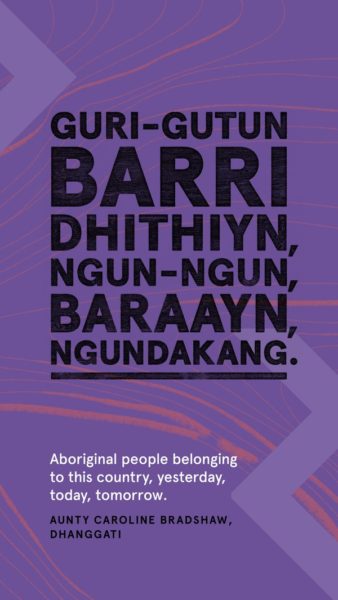

Image Credit: Dreamtime Creative by Jordan Lovegrove, Ngarrindjeri; from 2023 Annual Closing the Gap Report and 2024 Implementation Plan (p. 10) © Commonwealth of Australia, Commonwealth Closing the Gap Implementation Plan 2024

Editor’s Note: The Australian Commonwealth’s Closing the Gap 2024 Annual Report and 2025 Implementation Plan was released earlier this week. In this post, Kristen Martin reflects on progress towards one specific ‘Closing the Gap’ target, namely Target 16, which aims to strengthen Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages.

***

It has been four years since the Australian Government included Target 16 – to strengthen Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages – in the ‘Closing the Gap’ targets. What has been happening since Target 16 was announced? The status of Target 16 is officially ‘unknown’ (as of July 2023), and the fourth National Indigenous Language Survey will not be published until 2026 but what has progress looked like so far? There is already some exciting, new work happening, as this blog will outline.

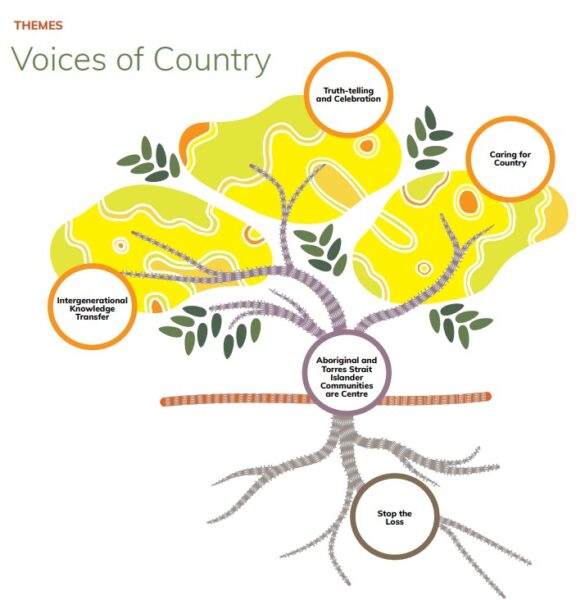

Voices of Country

A collaboration between the Australian Government, First Languages Australia and the International Decade of Indigenous Languages Directions Group, the Voices of Country Action plan is described as “framed through five inter-connected themes:

- Stop the Loss

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Communities are Centre

- Intergenerational Knowledge Transfer

- Caring for Country, and

- Truth-telling and Celebration.”

The purpose of the initiative is to pilot actions towards language strength based on community decisions, outlining various ways governments can approach the Closing the Gap targets. In a report released about the 10-year action plan, it outlines:

However, the Voices of Country Action plan is only one of many plans that the Australian government has invested in!

Language Policy Partnership

Alongside the Voice to Country Action plan, a key milestone in the progression of Target 16 is the establishment of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Language Policy Partnership, established December 2022 and known as the LPP. The LLP seeks to “establish a true partnership approach with truth-telling, equal representation and shared decision-making fundamental to the National Agreement for Closing the Gap”.

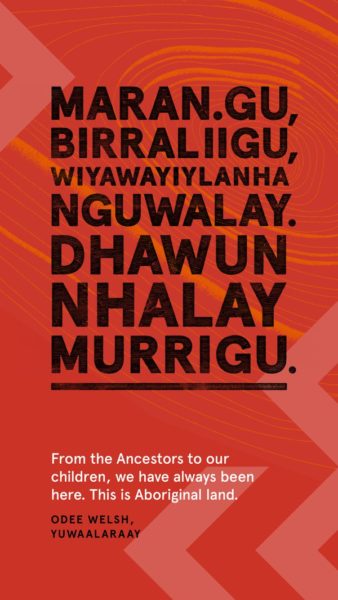

Image credit: The Wattle Tree graphic design agency by Gilimbaa with cultural elements created by David Williams (Wakka Wakka), acknowledging also the Traditional Custodians: © First Languages Australia and Commonwealth of Australia 2023, Voices of Country – Australia’s Action Plan for the International Decade of Indigenous Languages 2022-2032, p.9

The program is a collaboration between the Coalition of Peaks, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander language experts, and various government members. Through the LPP and discussions with various communities, seven priorities have been outlined to make progress on Target 16 and strengthen Indigenous languages. The priorities are as follows:

- Speaking and using languages

- Supporting the people, groups and organisations who work in languages

- Languages legislation

- Access to Country

- More funding that goes where communities need it

- Bringing language home to the people and communities

- Help people understand the importance of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Languages

From this commitment, the LPP has also said

Since its establishment, the organisation has met seven times with published documents reflecting their discussions available.

The Australian Government has invested $9.7 million into the LPP and states the program will undertake evaluation after three years (in 2026).

A lookback on previous Target 16 process

As Alexandra Grey has noted back in 2021, funding for the Indigenous Languages and Arts (ILA) program had been planned for the progression of Target 16. The ILA, in collaboration with First Languages Australia saw 25 language centres open throughout the country and teach the various languages in their surrounding areas. Following this, the ILA has also said it will invest over $37 million in 2024-2025 to “support Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to express, conserve and sustain their cultures through languages and arts activities throughout Australia.”. What this funding will go to in 2025, we will have to wait and see.

International Decade of Indigenous Languages

Australia is not the only country to care about the status of Indigenous languages, as we are currently in the middle of the United Nations’ International Decade of Indigenous Languages (2022 – 2032). Following the UN’s International Year of Indigenous Languages in 2019, the UN has established this decade to focus on the “preservation, revitalization and promotion” of Indigenous languages. Australia is one of many countries to be a part of this celebration, developing the ‘Voices of Country’ Action Plan as “a call to action for all stakeholders”.

Impact of these actions

Of the many partnerships in place, it appears the Australian government has taken a community-based approach for this goal, consulting with community members and First Nations representatives for official and efficient actions. With all the great initiatives underway, it is easy to assume that progression with Target 16 is happening. However, we will not be able to truly know the effects of these initiatives until 2026 as we wait on the fourth National Indigenous Language Survey and the LPP program evaluation.

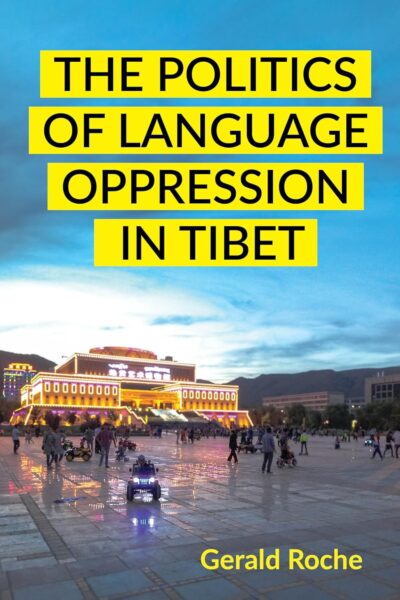

]]>Tazin and Gerald discuss his research into language oppression and focus on his recent book The Politics of Language Oppression.

In The Politics of Language Oppression in Tibet, Gerald Roche sheds light on a global crisis of linguistic diversity that will see at least half of the world’s languages disappear this century.

In The Politics of Language Oppression in Tibet, Gerald Roche sheds light on a global crisis of linguistic diversity that will see at least half of the world’s languages disappear this century.

Roche explores the erosion of linguistic diversity through a study of a community on the northeastern Tibetan Plateau in the People’s Republic of China. Manegacha is but one of the sixty minority languages in Tibet and is spoken by about 8,000 people who are otherwise mostly indistinguishable from the Tibetan communities surrounding them. Recently, many in these communities have switched to speaking Tibetan, and Manegacha faces an uncertain future.

The author uses the Manegacha case to show how linguistic diversity across Tibet is collapsing under assimilatory state policies. He looks at how global advocacy networks inadequately acknowledge this issue, highlighting the complex politics of language in an inter-connected world. The Politics of Language Oppression in Tibet broadens our understanding of Tibet and China, the crisis of global linguistic diversity, and the radical changes needed to address this crisis.

Related content

You can read more of Gerald’s work in his blogposts.

Transcript (coming soon)

]]>***

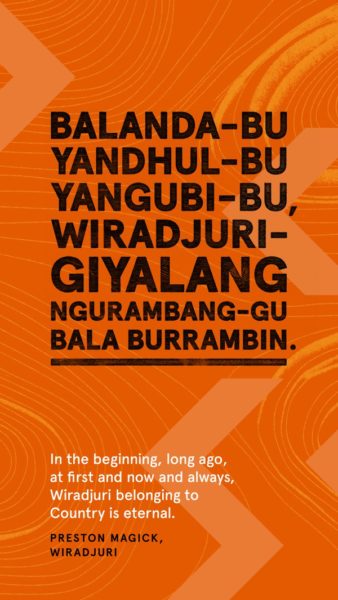

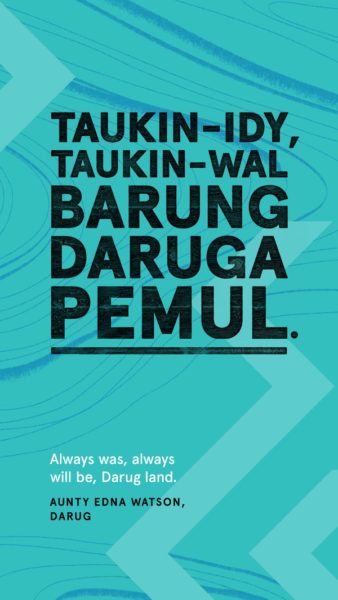

Editor’s note: This week (Nov 08-15) we are celebrating NAIDOC week. “NAIDOC” stands for “National Aborigines and Islanders Day Observance Committee.” The theme of this year’s NAIDOC week is “Always was, always will be” in recognition of the fact that First Nations people have occupied and cared for the Australian continent for over 65,000 years. Indigenous Languages have been a inextricable part of this history. Yet the value of Indigenous Languages continues to be denied, as Gerald Roche and Jakelin Troy show here.

***

A New Era for Indigenous Languages?

Despite decades of research and public outreach demonstrating the importance of Indigenous languages, negative attitudes about the maintenance and revitalization of these languages persist among the general public in Australia. Here, we argue that we need to think about the tenacity of these negative attitudes as a form of denial, like climate denial or genocide denial. We also argue that now is a crucial time to confront that denial.

2019 was nominated by the UN as the International Year of Indigenous Languages, and the years 2022-2032 have been nominated as the decade of Indigenous languages. These high-profile international mega-events seemingly promise a coming era of unprecedented attention to and support for Indigenous languages.

This promise extends to Australia. We joined in the International Year of Indigenous Languages, with numerous activities organized by the Department of Communication and the Arts. The Australian Institute for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies recognized 2019 as an “opportunity for all Australians to engage in a national conversation about Indigenous languages.”

Australia is the only country in the world that has a national schools curriculum that supports the teaching of all its Indigenous languages. ‘The Australian Curriculum Languages – Framework for Teaching Aboriginal Languages and Torres Strait Islander Languages’ provides for every school in Australia to teach one or more Australian languages—the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages. In spite of this historic development in our education system, most Australians seem to be oblivious or, worse, hostile to Australian languages. Plans are now afoot to take part in the coming decade of Indigenous languages, but how will Australia support Australian languages?

Ongoing trends and recent events in Australia suggest that significant challenges lie ahead. The Third National Indigenous Languages Report, published in August this year, found that most of Australia’s Indigenous languages are highly ‘endangered,’ while only a small and declining number (currently 12) are considered ‘strong.’ Meanwhile, recent efforts to bolster the role of English, seen in new regulations enforcing English requirements for partner visas, have strengthened problematic associations between the English language and Australian citizenship. And most disturbingly, we continue to see the destruction of Indigenous heritage by both commercial and state parties.

All of this suggests that Australia must still confront massive social and political barriers if Indigenous languages are going to flourish. As the analysis below demonstrates, denial of the importance of Indigenous languages and the reality of their revitalization persists, and are expressed in public forums with surprising impunity.

Indigenous Languages and the Australian Public

We undertook a preliminary analysis of comments made on five articles in the Conversation, published between August 2014 and July 2020; the data we analyze is available here. These articles focused on different aspects of the maintenance and revitalization of Indigenous languages in Australia. We collated a total of 49 comments from them.

We began by classifying the comments into negative, positive or both/neither regarding their view of Indigenous languages. We found that 21 (42.8%) of the comments were unambiguously negative in their appraisal, while 14 (28.5%) were positive; the remaining were either neutral or ambiguous.

We then examined the negative comments for recurrent themes that were used to justify and rationalize these views. We found five major themes: language revitalization is impractical; it harms Indigenous people and communities; revitalized languages are inauthentic; government support for Indigenous languages is inappropriate, and; English should be promoted instead of Indigenous languages. Each theme is examined in turn below.

Commentators suggested that it was “impractical,” “absurd,” or not “feasible” to maintain and revitalize Indigenous languages, or that these languages are “doomed,” and therefore any interventions were useless. Some commentators took a modified position, suggesting that the proposed methods, rather than revitalization itself, were impractical. One commentator attempted to demonstrate the impracticality of supporting Indigenous languages with a hypothetical scenario: a factory in an “Aborigine area” where all signage would have to be in English as well as “the various Aboriginal languages/dialects,” leading to an unsafe work environment.

Another theme was that maintaining and revitalizing Indigenous languages is harmful. Some suggested that supporting Indigenous languages has adverse economic impacts, primarily because English is the language of economic advancement: “English, in Australia must be the language of the classroom as it will be the key to the factory, office and other workplaces.” Others stressed that supporting Indigenous languages would isolate Indigenous people: from the rest of society, in remote locations, and in the past. Support for Indigenous language was associated with Indigenous people living “in the desert, isolated from mainstream society,” “condemned” to becoming a “living museum,” unable to “appreciate their links to people in other regions.” A variant of this argument was that providing support for language revitalization takes funds away from communities where Indigenous languages are strong.

Commentators also employed a ‘bootstraps’ argument, insisting that government interventions in Indigenous languages were inappropriate because communities should take sole responsibility for their languages. One commentator stated that “The real responsibility lies within each community to promote language usage,” while another emphasized the need for “a grass roots commitment within the community.” This point was often stressed by making comparisons with successful efforts of migrant communities to maintain their languages in Australia. These comments seemingly imply that if Indigenous communities need government support, it is because they are either unwilling or unable to maintain their languages themselves.

A fourth theme in the negative comments focused on issues of authenticity. It was argued that the languages, speakers, or the use of languages were, essentially, fake. Regarding revitalized languages, it was argued that, “We don’t know what the languages were really like,” and that we can “never know” their pronunciation. Not only were the languages described as fake, but it was also asserted that, “Aboriginal people are really English speakers.” Finally, the use of such languages is also deemed inappropriate in the modern world, in places that “are now completely covered in concrete, industry, and modern life.”

A final theme was that English should be prioritized. The importance of English was sometimes suggested to derive from its official status: “English is the official language in Australia.” More often, it was suggested that English ‘simply is’ the dominant language, and that prioritizing it is mere realism: “Living in Australia means speaking English.” One commentator also suggested that English is a “very rich language,” that contains “the words needed for modern, global life.” This suggests that Indigenous languages are, by contrast, ‘poor’ and have vocabularies unsuited to ‘modern, global life.’

Understanding Denial

All the positions outlined above constitute denial insofar as they are counterfactual. In contrast to what these commentators suggest, language revitalization is thriving in Australia. Many languages of the south east and south west of Australia have come back into active use after more than one hundred years of dormancy. One such language is Kaurna of the Adelaide Plains, not spoken for more than one hundred years when its community began to reconstruct the language from sparse memories and some historic documents, assisted by linguist Rob Amery. It is now a thriving language with its community using the language on a daily basis for casual and formal communication. It began with the community wanting to teach the language in their schools and this continues today.

Rather than harming Indigenous people, language revitalization is linked to increased wellbeing. In talking about the renewal of Kaurna and other languages, Kaurna educator Stephen Goldsmith says, “When we’re talking about the Aboriginal culture, we’re talking about the cultural heritage of every Australian…When people go into communities they start to understand the depth and the knowledge of Aboriginal people and how we operate as part of the environment.”

Although language revitalization requires commitment from the community, it also requires government support, in both policy and funding. And languages that have undergone renewal of their use as community languages are as real and authentic as any language. Finally, English is not Australia’s official language nor is it an Australian language; it is a language of Australia, imported like the many others that are now languages of Australia.

These are all established facts, accessible to anyone who cares to look. There are debates about details, but not basic truths. Therefore, if the comments we analyze are expressions of ignorance, it is willful ignorance. More than merely counterfactual, however, these arguments are also denialist in the sense that they aim to obstruct a course of action that is suggested by those recognized facts. In this case, they aim to justify and rationalize an unjust status quo that Indigenous people have persistently spoken up against.

The denialist arguments described above follow a common pattern shared with denialist efforts to suppress language revitalization elsewhere. However, they also exist in a uniquely Australian context, and an important aspect of this context is anti-Indigenous racism. A recent survey found that three quarters of Australians hold ‘implicit bias’ against Indigenous people, and the Online Hate Prevention Institute has tracked rising anti-Indigenous racism in Australian online space, particularly following this year’s Black Lives Matter protests.

We need to better understand the relationships between anti-Indigenous racism and the denialist positions described here.

If the UN decade of Indigenous language is going to truly help Indigenous languages in Australia flourish, it will be essential to understand both the extent of denialist sentiments, and the complex ways they interact with the wider political context. Broad public support will be essential to promoting Indigenous languages: to create a safe space where Indigenous people can undertake the difficult and emotional work of reclaiming their languages; to protect communities and individuals from backlash; to ensure that funding is secured and its use supported; and as an essential part of any political change within our democratic political system.

To win this support, we have to stop denying the existence of denial, try and better understand how and why opposition to Indigenous language revitalization exists, and explore how it might be countered.

]]> Editor’s note: We find ourselves in a time of deep global crisis when reflections on research ethics take on new urgency. Language on the Move is delighted to bring to you a series of texts that aim to rethink research ethics in Applied Linguistics. The texts in this series have been authored by members of the Research Collegium of Language in Changing Society (RECLAS) at the University of Jyväskylä in Finland. Their frustrations with a narrow legalistic understanding of ethics brought them together in a series of meetings and long debates in unconventional contexts, where they explored an understanding of ethics as foundational to and intertwined with all aspects of doing research. The result of these meetings and conversations is a series of “rants”, which they share here. In this first rant, Petteri Laihonen reflects on the ethics of methodological approaches and conceptual frameworks.

Editor’s note: We find ourselves in a time of deep global crisis when reflections on research ethics take on new urgency. Language on the Move is delighted to bring to you a series of texts that aim to rethink research ethics in Applied Linguistics. The texts in this series have been authored by members of the Research Collegium of Language in Changing Society (RECLAS) at the University of Jyväskylä in Finland. Their frustrations with a narrow legalistic understanding of ethics brought them together in a series of meetings and long debates in unconventional contexts, where they explored an understanding of ethics as foundational to and intertwined with all aspects of doing research. The result of these meetings and conversations is a series of “rants”, which they share here. In this first rant, Petteri Laihonen reflects on the ethics of methodological approaches and conceptual frameworks.

To view the other RECLAS ethics rants, click here.

***

Approaches, frameworks, methodologies, and research designs have consequences for research ethics. Here I will discuss some things I have learned in my career as a fieldworker and researcher mainly while meeting minority language speakers in remote places and while trying to formulate practical relevance of my research for the wider public. I will specifically address the perception of research by research participants, and the ethics of interviewing and other methods. I will close by sharing my take on researcher activism.

What’s in it for research participants?

All research should ideally benefit the researched communities and individuals in some meaningful and sensible way.

In general, participants have been happy to discuss language issues with me, some have even considered the interviews as an opportunity to tell their life stories to somebody and to have it recorded. Others mentioned, that, as a linguistic minority, they have been “forgotten”. Participating in research felt like a good way to them to place their lives or their village on the map.

Petteri with research participants during fieldwork (Photo by Karina Tímár)

To meet my participants’ expectations, I have found it especially important to publish and present results not only in dominant languages and academic forums but also in the local language(s) and in accessible forums: in my case that has meant Hungarian and open access journals. Research published in English is largely irrelevant to my participants as it is mastered only by few of them.

In short, I consider it an important part of research(er) ethics to practice multilingual research multilingually (see Piller 2016 on the critique of doing research on multilingualism monolingually).

Beyond the research interview

In my dissertation, I provided detailed analyses on the constraints of the research interview as an ‘objective’ research tool by pointing out that the views on language produced in an interview are co-constructed by the interviewee and the interviewer. This helped me to see the research participants and researchers as equal partners in the production of information and knowledge, and my dissertation work made me very critical also towards objectivizing stances to research interviews. For example, certain things are often mentioned (or not and in a certain way) by an ‘informant’ only because they were asked (or not) by the researcher (in a certain way).

Most importantly, however it turned my attention to research ethics of treating the people we study as equal research participants, not merely as ‘informants’.

During my post-doctoral project (2011—2013), I became interested in the study of linguistic landscapes. The study of linguistic landscapes, or visual semiotics represents a turn “from spoken, face-to-face discourses to the representations of that interaction order in images and signs” (Scollon & Wong Scollon 2003: 82). In my current project (2016–2021), my fieldwork and data generation has also been focused on visual methods.

Originally developed to minimize the impact that researchers have on shaping the data, these methods have the potential to address the basic challenge research interviews have: interviewing appears to put the researcher in a dominant position.

Practicing inclusive research

Taking the concerns of research participant’s positionality and agency vis-a-vis the researcher seriously is a cornerstone of inclusive research. In my current project, I employed a local research assistant, who has been a significant help in building shared interest with the participants and partner institutions.

Revitalization program teachers have come to see our research as beneficial, especially due to the use of digital visual methods, which have provided examples of pedagogical experiments. To take one example: we have carried out iMovie projects with children, where the children’s first video recorded their villages and self-selected topics at home with an iPad provided by the project. Then they edited iMovies with the iPads during a revitalization class and finally showed the final recordings to other children, researchers, parents, and teachers.

Fieldwork projects, such as the iMovie project have served my research aims to gain analysable data through visual methods and thus getting access to participant language views and language practices.

Teachers’ views of research may have been changed as well: some more experienced teachers mentioned that previous research has not been similarly rewarding and that it had been difficult to engage the children in activities such as filling out questionnaires and surveys. In our case, they could see an immediate benefit for the program in the heightened student motivation to use the revitalization language.

Should researchers be activists?

To address this question, I need to begin by reflecting on my analytical framework, the study of language ideologies. I define language ideologies broadly as common linkages between language and non-linguistic phenomena in a given community. In the study of language ideologies I follow, it is a basic assumption that no idea or view about language comes from nowhere. As Silverstein (1998:124) explains:

We might consider our descriptive analytic perspective […] as a species of social-constructionist realism or naturalism about language and its matrix in the sociocultural realm: it recognizes the reflexive entailments for its own praxis, that it will find no absolute Archimedian place to stand – not in absolute “Truth”, nor in absolute “Reality” nor even in absolute deterministic or computable mental or social “Functional Process”. Analysis of ideological factuality is, perforce, relativistic in the best scientific (not scientistic) sense.

From an ”activist” approach, we could investigate how inequality is constructed through language ideologies and then show how such language ideologies are untrue, or “bad” representations of reality or how ideology is produced by “false consciousness” (as argued by Marx, see Blommaert 2006). Such an interpretation of ideology as a distortion of reality performed in order to naturalize a questionable political ideology, has been embraced by certain strands of Critical Discourse Analysis, where the analyses thus examine different linguistic forms and processes of twisting the truth (e.g., the use of metaphors to mislead interpretation, see Reisigl & Wodak 2001).

However, the activist goal of “speaking truth to power” is not an aim shared by researchers in linguistic anthropology, since language ideologies are everywhere and due to the lack of the “Archimedian place” mentioned by Silverstein above, they are false or true according to the perspective we choose or premise we follow (see also Gal, 2002).

To conclude, our research participants and their communities should benefit from the research. To reach this goal, my approach has been to focus on inclusive ethnography and methods of data collection that provide meaningful activities, events and discussions for the research participants and participating institutions. I have focused on examples of best practices, and at the same time remained critical by not trying to pretend that I can speak truth to power.

Finally, a goal for every study should also be to help people understand why research in general is needed and beneficial for people outside of academia.

References

Blommaert, J. 2006. Language Ideology. In Brown, K. (ed). Encyclopedia of Language & Linguistics. Second edition, vol. 6. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 510-521.

Gal, S. 2002. Language Ideologies and Linguistic Diversity: Where Culture Meets Power. A magyar nyelv idegenben. Keresztes, L. & S. Maticsák (eds.). Debrecen: Debreceni Egyetem, 197-204.

Nind M. 2014. What is inclusive research? London: Bloomsbury.

Piller, I. 2016. Monolingual ways of seeing multilingualism. Journal of Multicultural Discourses, 11(1), 25–33.

Reisigl, M. & R. Wodak 2001. Discourse and Discrimination. Rhetoric’s of Racism and Anti-Semitism. London: Routledge.

Scollon, R. & Wong Scollon, S. 2003. Discourses in place. Routledge: London.

Silverstein, M. 1998. The Uses and Utility of Ideology: A Commentary. Language Ideologies: Practice and Theory. Schieffelin, B., K. Woolard & P. Kroskrity eds. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 123-148.

In his 2005 article ‘Will Indigenous Languages Survive?’ Michael Walsh described language revitalization as ‘profoundly political’. And Jacqueline Urla, in discussing the Basque language movement, has said that language revitalization can “never be divorced from politics.”

In his 2005 article ‘Will Indigenous Languages Survive?’ Michael Walsh described language revitalization as ‘profoundly political’. And Jacqueline Urla, in discussing the Basque language movement, has said that language revitalization can “never be divorced from politics.”

But if language revitalization is political, just what sort of politics is it?

Here, I want to think about language revitalization as a form of radical politics, based on a reading of the recently published Routledge Handbook of Radical Politics.

To begin with, what is radical politics?

Radicals don’t propose a single definition of the concept. My understanding of radicalism is that it is oppositional, and seeks fundamental transformation (rather than superficial tweaks), through the abolition of various forms of domination. In this sense, language revitalization is radical, because it challenges the global status quo: a planetary system of language oppression that is presently eliminating at least half of the world’s languages.

Language revitalization seeks a different world, not a better version of this one. It seeks a world where structural power arrangements allow all languages to flourish. This requires a fundamental transformation of current social and political arrangements, which are presently geared towards the elimination of Indigenous peoples and the continuing subordination of other groups according to race, ethnicity, caste, and religion.

Radical politics seeks to achieve this transformation through direct action. Although campaigning, lobbying, consciousness-raising, and other forms of progressive politics are part of the radical toolkit, more important are acts of civil disobedience, protest, disruption, hacktivism, and so on.

Moments of direct action have always preceded language revitalization movements. Such movements can only occur in the context of greater rights, expanded freedoms, and diminished domination that are won through struggle.

A key case in point is the revitalization of Indigenous languages in settler colonies such as Australia, the USA, Canada, and New Zealand. In all these contexts, larger revitalization movements emerged out of earlier efforts to maintain languages only after civil rights had been secured through protest and other forms of direct action. States did not grant these rights willingly; rather, these rights were won as a result of coordinated, purposeful, direct action by Indigenous peoples, fighting simultaneously in their homelands whilst networked across the globe.

Language revitalization is also connected to direct action in another way. If we accept that current structural arrangements lead to the elimination of certain languages, then simply using those languages is a form of direct action. In this sense, the anthropologist and Chickasaw language activist Jenny Davis has called language revitalization an “act of breath-taking resistance, resilience, and survivance.”

Language revitalization is also connected to direct action in another way. If we accept that current structural arrangements lead to the elimination of certain languages, then simply using those languages is a form of direct action. In this sense, the anthropologist and Chickasaw language activist Jenny Davis has called language revitalization an “act of breath-taking resistance, resilience, and survivance.”

In addition to direct action, language revitalization demonstrates another important feature of radical politics: prefiguration. Prefiguration refers to efforts to create the sought-after forms of justice in the process of achieving structural transformation: to prefigure the world one wants to build. Language revitalization is prefigurative in that it restores languages to a community and the world before broad-scale transformation has taken place, as a model of how the world could and should be.

In addition to direct action and prefiguration, another important feature of radicalism is critique. It aims to name, describe and expose systems of domination, and to clearly outline their harms and their perpetrators. Radical politics is thus typically ‘anti’: antifascist, antiracist, anti-capitalist, antimilitarist, anticolonial, anti-imperialist, anti-patriarchy.

This sort of critique has so far played only a limited role in language revitalization. Instead, discourses of language revitalization, particularly in the popular imagination, have been dominated by tropes of what Jane Hill called ‘hyperbolic valorization’: the heaping of abundant praise on these languages. Such praise, without a critique of domination, leads to what Daniel G. Solorzano and Dolores Delgado Bernal call ‘conformist resistance,’ which works towards social justice by offering ‘Band-Aid’ solutions that do not address deeper, systemic issues.

However, a structurally-informed critique is gradually emerging in relation to language revitalization. For example, Alice Taff and her collaborators use the term ‘language oppression’ to describe the ‘enforcement of language loss by physical, mental, social and spiritual coercion,’ and I have written about how language oppression can be analyzed similarly to other forms of oppression that occur in relation to race, nation, ethnicity, and religion. Indigenous scholars such as Wesley Leonard, Jenny Davis, and Michelle M Jacob are increasingly tying language revitalization to a critique of colonialism. Feargal Mac Ionnrachtaigh, in discussing the radical language politics of political prisoners in what is currently Northern Ireland, ties their language revitalization work to broader struggles against colonialism and neo-colonial globalization. And in Australia, Kris Eira has stated that, “what causes the loss of languages is dominance of one group of people over another.” Together with Tonya Stebbins and Vicki Couzens, Kris Eira has therefore called for the decolonization of linguistic practice.

This focus on a critique of colonialism and a positive project of decolonization increasingly forms a central aspect of radical politics, due to efforts to ensure that radical politics are intersectional. This means that radical projects explore how varying forms of domination and oppression interact, through discussion of concepts like racial capitalism, environmental racism, and the decolonization-decarbonization nexus. They also seek to ensure that radical projects do not create injustice for some while seeking justice for others, for example, through anti-oppression policies.

This focus on a critique of colonialism and a positive project of decolonization increasingly forms a central aspect of radical politics, due to efforts to ensure that radical politics are intersectional. This means that radical projects explore how varying forms of domination and oppression interact, through discussion of concepts like racial capitalism, environmental racism, and the decolonization-decarbonization nexus. They also seek to ensure that radical projects do not create injustice for some while seeking justice for others, for example, through anti-oppression policies.

Because radical politics seeks to be intersectional, solidarity is central to its practice: solidarity within, across, and between movements. The first type of solidarity is highly relevant to language revitalization, given its communal nature. Thinking about solidarity as a form of negotiated goal-setting and coordinated action seems to provide a more constructive way of dealing with the conflicts that often arise in the process of language revitalization, compared to present interests in achieving ‘ideological clarification’.

Solidarity across movements refers to how people outside a movement can act as advocates, allies, affiliates, or accomplices to those within it. For example, I see my role as that of an ally for linguistic justice, rather than a language revitalization practitioner. One thing I think we can usefully do as allies is to help create safer spaces for language revitalization. As Ruth A. Deller explains in the handbook, safer spaces are those where, “…people from different marginalized groups can gather, speak and be resourced safely”—these may be physical or virtual. Whatever practices of solidarity we engage in, it is crucial to think about how we can decolonize solidarity—how we avoid reproducing the power structures and relations that cause language oppression in the first place.

Thinking about the third form of solidarity—between movements—provides a critical insight into an important shortcoming of the Routledge handbook. In a volume containing a chapter on radical bicycle politics and another dedicated to discussing what does and does not constitute radical music, language barely rates a mention. In a book that takes intersectionality and decolonization as organizing principles, the near total absence of any discussion of language is indicative of the need for a more expansive and more inclusive vision of what counts as radical politics.

This presents an opportunity for language activists, advocates, and allies to engage with radical academics and activists. We need to demonstrate how any analysis of oppression is incomplete without understanding the ways in which language serves as a contour of domination and an objective for emancipation. In turn, we have much to gain from a deeper engagement with the practices and philosophies of radical politics.

Acknowledgement

Many thanks to Shannon Woodcock, Christopher Annis, Rokhl Kafrissen, and Ingrid Piller for discussions and comments that helped improve this article.

]]>

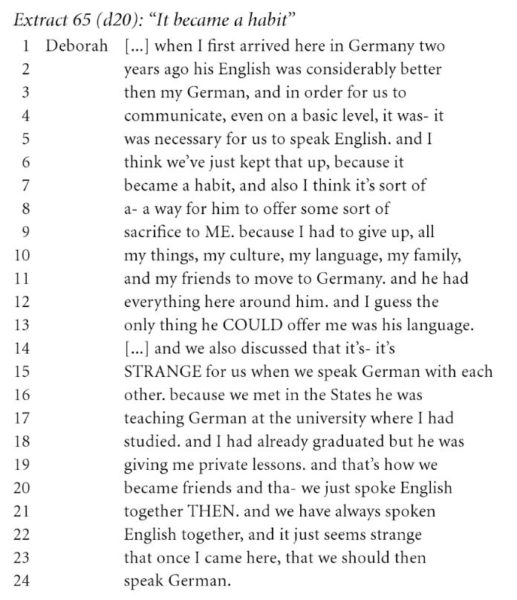

Language choice in bilingual couples as habit (excerpt from Piller, 2002, p. 137)

In my research with bilingual couples, habit emerged as one of the main reasons for a couple’s language choice. Partners from different language backgrounds met through the medium of a particular language and fell in love through a particular language. Once they had established a relationship through that language, it became a relatively fixed habit.

This means that entering a couple relationship was a moment of linguistic habit formation. At the same time, it was also a moment of drastic linguistic habit change, at least for one partner. At least one partner had to change their habitual language from one language (usually their native language) to another (usually an additional language).

The question of habit formation is an important one in language learning research. Around the world, education systems invest enormous sums of money into language teaching but the outcomes in terms of getting students to actually speak the language(s) they are learning outside the classroom are often unclear.

Efforts to revive Irish Gaelic provide a well-known example. In the Republic of Ireland, Gaelic is part of the compulsory curriculum of primary and secondary school students. Even so, only around 40% of the population reported in the 2016 census that they could speak Irish. However, when asked whether they actually did so, only 1.7% of the population reported that they regularly used Irish. So, knowing Gaelic and using Gaelic are clearly two different things.

The explanation for this pattern is simple: habit. Studying a language gives learners a new tool. But to actually use that tool on a regular basis outside the classroom requires a change of linguistic habit. In other words, language knowledge needs to be activated.

For the native German speakers in my bilingual couples research, falling in love and establishing a couple relationship with a native English speaker provided such a transformative moment that allowed them to activate the English they had studied throughout their schooling. (The converse pattern was much rarer as native English speakers rarely had studied German and so no basis for a linguistic change of habit existed).

Other than linguistic intermarriage, what transformative moments are there across the life course when people might change from one habitual language to another?

Professor Maite Puigdevall during her guest lecture at Macquarie University

This is the question Professor Maite Puigdevall (Universitat Oberta de Catalunya, Spain) addressed in her inaugural lecture in linguistic diversity at Macquarie University. Professor Puigdevall and her colleagues use the Catalan word muda (“change, transformation”) to refer to such biographical junctures where a linguistic change of habit is likely. They have identified six such transformative junctures across the life course:

- Primary school

- High school

- University

- Workplace entry

- Couple formation

- Becoming a parent

At each such juncture, a person starts to move in new circles, make new friends and establish new networks. Establishing oneself in such a new way may lead to all kinds of changes and new habits and a switch in the habitual language may be one such transformation.

Professor Puigdevall and her colleagues have used the muda concept particularly in relation to minoritized languages such as Catalan, Basque or Gaelic. At each juncture, such languages acquire “new speakers” (as opposed to the ever-shrinking number of heritage speakers). However, the life-course approach they propose has at least two implications for language policy elsewhere, too, including Australia.

First, language learning is a long-term investment. Results should not be expected immediately but are more likely to accrue later in life. A good reminder that the old adage non scolae sed vitae discimus (“we learn not for school but for life”) holds for language learning, too, and that we should vigorously contest the “languages are useless” argument that we so often hear, particularly in the Anglosphere.

Second, an investment in language education in school will pay off most when it is complemented by other policy interventions in favor of a particular language. For instance, in comparative research related to Catalan, Basque and Gaelic, Professor Puigdevall and her colleagues found that a significant inducement to turn Catalan into a habitual language was constituted by the bilingual (Catalan, Spanish) language requirement present for employment in the civil service in Catalonia.