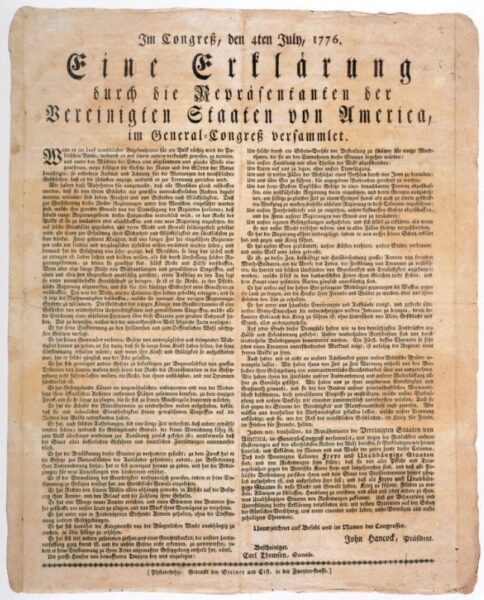

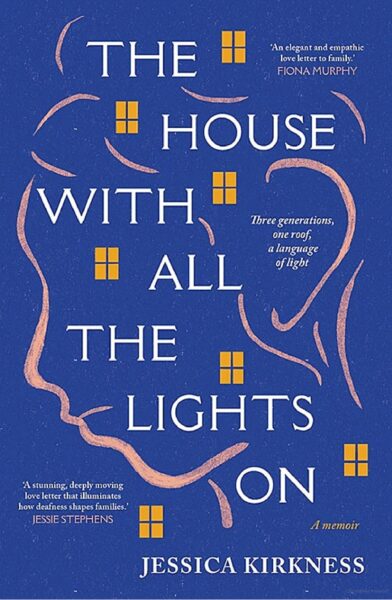

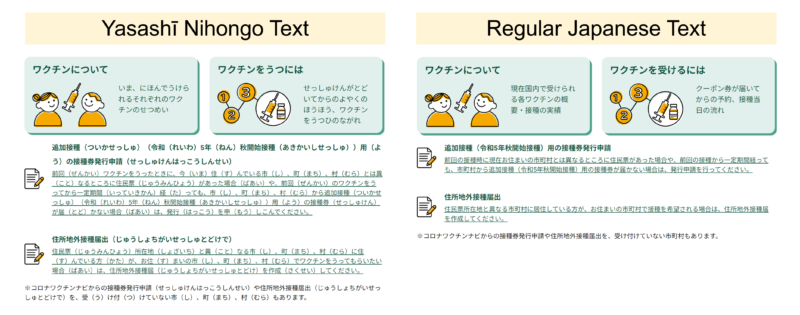

Ukrainian migrant asking ChatGPT to explain different types of rental contracts in Austria (still from Yudytska & Androutsopoulos 2025)

For nearly four years now, I’ve been heavily involved in online (Telegram-based) communities for Ukrainian forced migrants in Austria. Such communities sprang up all across Europe after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in early 2022, serving as grassroots digital info-points. In those early, chaotic days, the groups focused on a Ukrainian’s first steps upon getting off the train in their new country. They have since expanded to cover everything from where to buy buckwheat (a very pressing question!) to the fine details of the local education system, health insurance, job market, etc.

The communities are run for Ukrainian refugees, by Ukrainian- and Russian-speakers, that is, overwhelmingly by migrants – forced, labour, student; first-gen, second-gen; etc. It truly is mutual aid: those who migrated earlier answer questions on integration, those who left recently give tips on how best to reach relatives in occupied territory. My family left in 1999, when I was five; I co-admin one group for Ukrainians in my home state of Upper Austria (ca. 3,700 members) and one group focused on how to change from the Temporary Protection status to a longer-term work/residence permit (ca. 8,300 members), plus I occasionally help out in other groups.

In 2025, our communities gained one more, less welcome, “member”: ChatGPT.

Migrants’ search for information

Understanding the role of ChatGPT in these communities requires understanding the complex informational space newly arrived migrants are in. There is an avalanche of info to take in. Some involves the everyday differences: when your child has a fever, at what temperature can you call the ambulance without getting in trouble for wasting their time? Other aspects are specific to the (forced) migrant status, and would stump a local too. Language barriers make accessing information difficult. Even with machine translation, it’s hard to know what term to google or how to interpret a bureaucrat’s answer.

This is where the Telegram communities come in, providing an easy place to ask for help and discuss problems.

An NGO’s German-Ukrainian sign about food and clothing distribution; the understandable but incorrect Ukrainian suggests machine translation (photo taken by author)

Still, they’re not a panacea. Us volunteers learned only on the fly the ins-and-outs of the Austrian asylum system in all its kafkaesque glory: we sometimes misremember, misunderstand, and mistranslate. Grasping a question can take real detective work, especially when there’s a dozen ways to translate a single German term. Official Austrian sources give a lot of information orally; this leads to bewildering discussions where one person informs the chat their social worker said X, another says it was Y, and the third Z. Maybe it’s miscommunication, maybe the official sources have no clue either.

Above everything loom the rumours, best illustrated by the (admittedly pretty sexist) Russian acronym, ОБС – одна бабка сказала, lit. “some old lady said”. It’s used in the sense of, “Uh-huh, riiight, you got that info from your cousin’s friend’s mom’s neighbour”. In 2027 all Ukrainians in the EU will be put on the next train home, even if the war is still ongoing. Truth or ОБС? Great (unanswerable) question!

Enter ChatGPT

Into all this chaos slams the iron certainty of ChatGPT. If it worked as advertised, it would be an invaluable resource for migrants. You ask a question, it searches for and provides a summary of official information. No linguistic barriers, no mistranslations, no complex legalese; no petty online fights to wade through. The appeal is clear.

The only tiny problem is that it doesn’t work as advertised.

The biggest issue is in how ChatGPT functions: it doesn’t search for and copy-paste information from a database, but rather generates a statistically likely sequence of tokens (words) based on the data it was trained on. This is why it can “hallucinate”, that is, make up answers which are linguistically coherent but factually untrue. It has also obviously been fed more data (law databases, official websites, forum discussions, etc.) from Germany than Austria. For example, it has confidently explained to a Ukrainian that she’s legally obligated to have health insurance – true in Germany, not so in Austria.

Linz Castle on the Danube, Upper Austria, lit up in the colours of the Ukrainian flag (photo taken by author)

The AI technique ‘Retrieval Augmented Generation’ (RAG) is meant to resolve this: ChatGPT first searches for and pulls relevant information from a website, then incorporates it into the answer. (ChatGPT uses RAG sometimes, but not constantly. It costs more energy, thus more money.) But the answer is still generated, so hallucination is still possible. This leads to ChatGPT claiming, for example, “According to the City of Vienna website, Ukrainians have to hand in their old refugee ID card. [Link to website]” Except its generated summary missed a negation: the website explicitly states Ukrainians do not have to hand in their old refugee ID card. RAG can thus lead to even greater misinformation, as it implies a direct source.

The other huge problem is the limited information actually available on migrant issues; even if hallucination was somehow solved, the adage of ‘garbage in, garbage out’ for machine learning remains. For example, to switch to a longer-term residence permit requires the migrant to have an ortsübliche Unterkunft (“housing according to local standards”). ChatGPT physically cannot answer what these local standards are. I know this because, according to my old-fashioned research techniques of searching law databases, skimming court cases, and asking lawyer friends, neither can anybody else! Unfortunately, it is too often the case that there is too little concrete info for ChatGPT to be trained on.

In short, using ChatGPT for information is a gamble. Sometimes it works great, sometimes it generates nonsense. To know which is which, the migrant is left with the same problem of surmounting the language barrier they started with.

Mutual aid with and against machines

Rows of donated women’s shoes at SUNUA, a grassroots organisation supporting Ukrainians in Upper Austria, 3 weeks post-invasion (photo taken by author)

I don’t consider myself a techno-pessimist – actually, I rely on language technologies heavily in my online volunteer work. My phone’s autocorrect is a life-saver. While I can read and write in Russian, I left Ukraine before starting formal education, and find it slow and frustrating to spell without autocorrect. Similarly, machine translation is a great help. I occasionally need it to double-check my understanding of more complex Ukrainian-language questions; I also machine translate German-language official updates for the sake of speed, then post-edit the Russian text to correct mistakes and stilted phrasing before posting.

That is, due to my background as a child migrant from a primarily Russian-speaking area of Ukraine, I have varying levels of competencies in the three languages I need: Russian, Ukrainian, German. For all their faults, language technologies are an invaluable resource for stuffing the gaps so I can help people successfully. And efficiently, as this has always been 100% unpaid labour in my free time, next to my full-time uni work.

But all this is why I find the intrusion of ChatGPT into our spaces so infuriating on a personal level. In the midst of a horrible situation, between fear, grieving, trauma, burnout, we’re all trying to use the linguistic and technological resources available to us to help each other. I accept arguing against a community member’s cousin’s friend’s mom’s neighbour’s experience as part of that – that connection is also a resource, and it’s human to trust an acquaintance over a fuzzily written law in a language you don’t speak yet. I’m willing to spend my free time picking apart where the confusion lies.

The author’s post in a Telegram group explaining that AI as a source must be clearly stated, with over 60 users leaving reaction emoji of agreement (screenshot taken by author)

I don’t accept arguing with ChatGPT screenshots.

ChatGPT adds beautiful formatting, with eye-catching emoji as bulletpoints. ChatGPT switches between Cyrillic and Latin easily, writing out German acronyms and translating them to Russian in brackets: ÖGK (Österreichische Gesundheitskasse – Австрийская касса медицинского страхования), wow. ChatGPT cites laws using a fancy § paragraph sign I have to copy-paste each time.

Sure, the actual information may or may not be correct, but that’s less important than the style, which so neatly mimics that of official sources. It simply looks trustworthy – the complete opposite of my own messages, written one-handed on a moving bus, with at least one butchered case suffix apiece. It’s unsurprising that people cling to ChatGPT’s information more stubbornly than to the usual ОБС.

Arguing against it is thus extra tedious and, frustratingly, requires me to do additional work. “Wait, no, where did you get that information from, is that an official source?” “Uh, nope, that website ChatGPT cited says the opposite.” “Dude, did you actually read the law ChatGPT ‘references’ – it’s about industrial chemicals, not document translation.” Most unsatisfactorily for all involved, having to prove a negative: “I’m sorry, but there’s no information on that. I don’t know why ChatGPT says there is, maybe it exists for Germany, but not for Austria.”

As a migrant who’s also stared at bureaucratic German in confusion and anxious despair, I don’t blame people for turning to AI. As a volunteer, it’s genuinely made me want to quit: in anger, in exhaustion, with a childishly vindictive, “Well, if they prefer machine over human, so long and thanks for all the fish.”

Where to next?

In principle, the issues explored here are no different from those we’re facing in other areas: education, academia, news, etc. Misinformation is rife everywhere; so is a lack of digital literacy on what current AI can and can’t do. For me, the crucial point is how vulnerable forced migrants are. Misuse of ChatGPT can lead not to a failed homework assignment but to problems on an existential level: with the legal status, with housing, with having enough money for food. Similarly, to put it bluntly, I’m paid to deal with students’ AI use; in volunteer work, it’s just one more weight tipping the scales in favour of finally quitting. It’s also important to add that not all my fellow admins share my worries. Some eagerly embrace ChatGPT answers themselves, which of course save time and energy for volunteers who have little of either to spare.

Our current ‘solution’ is that people must state openly that the information they’re posting is AI-generated. Then other members can decide themselves to what extent they trust it. In this, I would say, we’re ahead of the curve compared to many organisations, and for now, this will have to be enough.

Reference

Yudytska, J. & Androutsopoulos, J. (2025). The use of language technologies in forced migration: An explorative study of Ukrainian women in Austria. In M. Mendes de Oliveira & L. Conti (eds.), Explorations in Digital Interculturality: Language, Culture, and Postdigital Practices (pp. 135-166). Transcript. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783839476291-007

]]>NILS4 will be conducted in late 2025 to 2026 and reported upon in 2026.

There’s currently a national target in Australia about strengthening Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages by 2031. This is Target 16 in a policy framework called Closing the Gap. Zoe and I talk about how language strength can be measured in different ways and how the team have chosen to ask about language strength in this survey in ways that show clearly that the questions are informed by the voices in the co-design process.

Then we discuss the parts of the survey which ask about how languages can be better supported, for example in terms of government funding, government infrastructure, access to ‘spaces for languages’ and access to language materials, or through community support. The latest draft of the survey also mentions legislation about languages as a possible form of support. This is great; the data should encourage policy makers not to intuit or impose solutions, but rather to listen to what language authorities are saying they need. What I especially noticed in this part of the survey was the question about racism affecting the strength of a language – or reducing racism as a form of supporting languages – so I ask Zoe to tell me what led the team to include it.

We go on to discuss the enormous efforts and progress underway, and the love which many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities around Australia have for language maintenance or renewal. People may get the impression that language renewal is all hardship and bad news because a focus on language ‘loss’, ‘death’, or oppression pervades so much of the academic and media commentary. But Zoe and I both recently met in person at a fabulous, Indigenous-led conference in Darwin called PULiiMA in which delegates from 196 Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander languages participated. That’s just one indication of the enormous effort and progress around Australia, mainly initiated by language communities themselves rather than by governments. We talk about why, in this context, it’s important that this survey also has section about languages ‘flourishing’ and being learnt.

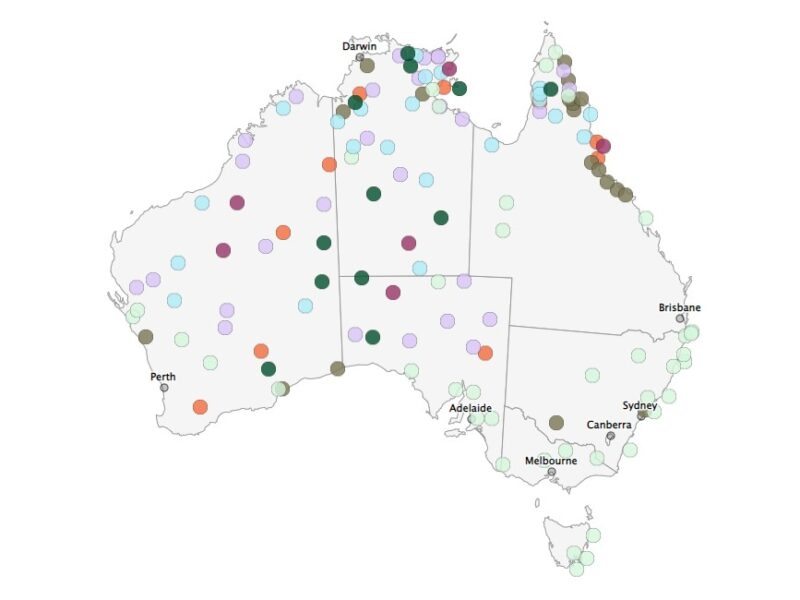

Language groups that participated in NILS3

We discuss the plans for reporting on the survey; incorporating the idea of ‘language ecologies’ was one of the biggest innovations in the National Indigenous Languages Report (2020) about the 3rd NILS and continues to inform NILS4. Finally, we talk about providing Language Respondents and communities access to the data after this survey is completed, in line with data sovereignty principles.

The survey should be available for Language Respondents to complete, on behalf of each language, in late 2025. AIATSIS will facilitate responses online, by phone, on paper and in person. If you would like to nominate a person or organisation to tell us about an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander language, please contact the team at [email protected]. Respondents will have the option of talking in greater depth about their language in case studies which AIATSIS will then include as a chapters in the report, as part of responding to calls in the co-design process to enable more access to qualitative data and data in respondents’ own words.

If you liked this episode, support us by subscribing to the Language on the Move Podcast on your podcast app of choice, leaving a 5-star review, and recommending the Language on the Move Podcast and our partner the New Books Network to your students, colleagues, and friends.

Transcript

Alex: Welcome to the Language on the Move Podcast, a channel on the New Books Network.

My name is Alex Grey, and I’m a research fellow and senior lecturer at the University of Technology in Sydney in Australia. This university stands on what has long been unceded land of the Gadi people, so I’ll just acknowledge, in the way that we do often these days in Australia, where we are. Ngyini ngalawa-ngun, mari budjari Gadi-nura-da and I’d really like to thank

Ngarigo woman, Professor Jaky Troy, who, in her professional work as a linguist, is an expert on the Sydney Language, and has helped develop that particular acknowledgement.

My guest today is Zoe Avery, a Worimi woman and a research officer at the Centre for Australian Languages. That centre is part of the Australian Institute for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, which we’ll call AIATSIS. Zoe, welcome to the show!

Zoe: Thank you! I’m really excited to be here and talking about my work that I’m doing at AIATSIS.

Alex: Yeah, so in this work at AIATSIS, you’re one of the people involved in preparing the upcoming National Indigenous Languages Survey. This will be the fourth National Indigenous Languages Survey in Australia. The first one came out now over 20 years ago, in 2005.

This time around, you and your team have made some really important changes to the survey design through the co-design process. Let’s talk about that. Can you tell us, please, what is the National Indigenous Languages Survey, what’s it used for, and how this fourth iteration was co-designed?

Zoe: Yeah, so, the National Indigenous Languages Surveys, or I’ll be calling it NILS throughout the podcast, they’re used to report the status and situation of Indigenous languages in Australia, as you mentioned. This is the fourth one. The first one was done all the way back in 2004 and, the third NILS was done about 6 years ago, in 2019. So it’s been a while, and it’s kind of just to show the progress of how, languages in Australia are being spoken and used, and I suppose the strength of the languages, which we’ll kind of go into a bit more detail. But the data is really important, because it can be used by the government to develop, appropriate language revitalisation programs or understand the areas that require the most support, but it can also be used by communities, which is really important as well.

And so, NILS4 has been a little bit different from the start compared to previous NILS, because the government has asked us to run this survey in order to measure Target 16 of Closing the Gap, which is that by 2031, languages, sorry, by 2031, there is a sustained increase in the number and strength of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages being spoken.

So, the scope for this project is much bigger than the past NILS, and AIATSIS has really prioritised Indigenous leadership in the design, and will be continuing to prioritise Indigenous voices in the rollout and reporting of the results of the survey.

So, because this is a national-level database, and we want to make sure as many languages as possible are represented, including previously under-recognized and under-reported languages, including sign languages, new languages, dialects. It’s really important that we have Indigenous voices, prioritized throughout this entire research process. And we want to make sure that the questions that are being asked in the survey are questions that the community want answers to, whether or not to advocate, to the government that these are the areas that need the most support, the most funding, or whether or not the community want that data for themselves to help develop, appropriate, culturally safe programs.

So what we did is we had this big co-design process, this year to design the survey. We had 16 co-design workshops with Indigenous language stakeholders across Australia, and this was, these workshops were facilitated by co-design specialists Yamagigu Consulting. We had, in total, about 150 people participate in the co-design process, and of these 150 people, about 107 of these were Indigenous. And so these Indigenous language stakeholders included elders, language centre staff members, teachers, interpreters, sign language users, language workers, government stakeholders, all sorts of different people that have a stake in Indigenous languages, for whatever reason. And we had 8 on-country workshops, which were held in cities around Australia, and 8 online workshops as well, which helps make it easier for, people that kind of came from different places, and weren’t able to come to an in-person workshop.

Alex: That’s a huge… sorry, just congratulations, that sounds like it’s been a huge undertaking. So many people, so many, so many workshops, well done.

Zoe: Yeah, it has been huge, and we’ve had so many different people from a variety of different language contexts, participate as well. So, the diversity of language experiences that were kind of showcased at these workshops was immense and has had a huge impact on drafting the survey, which is obviously the whole point of the workshops, but yeah … We took all the insights from the co-design workshops, we analysed them, thematically coded everything, and started incorporating everything into the survey. And then we went back to the people who participated in the co-design workshops and held these validation workshops so we could show them the draft of the survey, show them how we had planned on incorporating all of their insights, you know, that we weren’t just doing it for the sake of ticking a box to say, yes, we’ve had Indigenous engagement, but we were actually really wanting to have Indigenous input from the start, and right until the end of the project. And we had really good feedback from the validation workshops, and it is, you know, not just a massive task running these workshops, but also, making sure that everybody’s listened to, and sometimes they were kind of contrasting views about how things should be done, and yeah, we wanted to make sure that we had as much of a balance as possible.

We also consulted with the Languages Policy Partnership, which are kind of key workers in Indigenous languages policy and, advocacy. They’re kind of leaders in the Closing the Gap Target 16 that I was just talking about, so their input and advice has been really important to us, as have consultations with the Australian Bureau of Statistics and the Mayi Kuwayu Study of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Wellbeing. So yeah, there’s been a lot of input, and we’re really excited that we’re at the point now where we’re finishing the survey! Dotting all the I’s, crossing all the T’s and getting ready to start rollout soon.

Alex: Yeah, well, I mean, one would hope good input, good output! You know, such a huge process of designing it. You should get really well-targeted, really informative, useful results.

And you’ve mentioned a few things there that I’ll just explain for listeners, because not all our listeners will be familiar with the Australian context. It’s coming through that there’s enormous diversity of Indigenous peoples and languages in Australia, so to explain a little bit, because we won’t go into this in much detail in this interview, Zoe’s mentioned new languages like, contact languages, Aboriginal Englishes, Creoles, like Yumplatok, which comes from the place called the Torres Strait. If you’re not familiar with Australia, that area is between Australia, the Australian mainland, and Papua New Guinea, in the northeast. And then there’s an enormous diversity of what are sometimes called traditional languages across Australia, both on the mainland and the Tiwi Islands as well. So we have a lot of Aboriginal language diversity, and then in addition, Torres Strait Islander languages, and then in addition, new or contact varieties.

Zoe: Sign languages.

Alex: And sign… of course, yes, and sign languages. Thank you, Zoe. And then you’ve mentioned Target 16. So we have in Australia a policy framework called Closing the Gap. For the first time ever, the current Closing the Gap framework includes a target on language strength.

But as the survey goes in to, language strength can be measured in different ways. So how have you chosen to ask about language strength in this survey, and why have you chosen these ways of asking?

Zoe: Yeah, so, along with, kind of, Target 16 of Closing the Gap, there’s an Outcome 16, which is that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures and languages are strong, supported, and flourishing. So it’s important for us in the survey to, kind of, address those kind of buzzwords, strong, supported, and flourishing. But it is very clear, from co-design, that the widely used measures of language strength don’t necessarily always apply to Australian Indigenous languages. So these kind of widely used and recognised measures of how many speakers of a language are there, and is the language still being learned by children as a first language? These are not the only ways of measuring language strength, and we really wanted to make sure that we kind of redefined language strength in the survey based off Indigenous worldviews. So, language is independent [interdependent] with things like community, identity, country, ceremony, and self-determination.

How do we incorporate that into the survey? So we’re still going to be asking questions, like, how many speakers of the language are there? What age are the people who are speaking the language, but we’re also going to be asking questions on how many people understand the language, because people may not be able to speak a language due to disability, cultural protocol reasons, or due to revitalisation, for example. But they can still understand the language, and that can still be an indication of language strength. We’re also asking questions about how and where it’s used. So, do people use the language while practicing cultural activities, in ceremony, in storytelling, in writing, just to name a few? We know that Indigenous languages are so strongly entangled with culture and country, and it’s difficult to measure the strength of culture and country. But we can acknowledge the interdependencies of language, culture, and country, and by asking these kinds of questions, we can get some culturally appropriate and community-led ways of defining language strength.

Alex: And that’s just going to be so useful for, then, the raft of policies that one hopes will follow not just the survey, but follow the Target 16, and even once we get to 2031, will continue in the wake of, you know, supporting that revitalisation.

Zoe: Yeah, absolutely, and I think that, another thing that we heard from co-design, but just also from Indigenous people, in research and advocacy, that language is such a huge part of culture and identity, that by, you know, developing these programs and policies to help address, language strength, all the other Closing the Gap targets, like health and justice and education, those outcomes will all be improved as well.

Alex: Yeah, I guess that’s why, in the policy speak, language is part of one of the priority response areas for the Closing the Gap. And I noticed this round of the survey in particular is different from what I’ve seen in the earlier NILS in the way it asks questions, which also appears to reflect the co-design. So, for example, these questions about language strength, they start with the phrase, ‘we heard that’ and then a particular kind of way of thinking about strength. And then another way of thinking about strength might be presented in the next question: ‘We also heard that…’. So on, so on. So, is this so people trust the survey more, or are you conscious of phrasing the survey questions really differently compared to, say, the 2019 version of the survey?

Zoe: Yeah, absolutely we want people to trust the survey, and understand that we respect each individual response. Like, as much as it’s true, we’re a government agency, and we’ve been asked to do this to get data for Closing the Gap, we want language communities to also be able to use this data for their own self-determination, and we want to try and break down these barriers for communities and reduce the burden as much as possible. So, making sure that the survey was phrased in accessible language, and the questions were as consistent as possible.

But yeah, we wanted to make sure that we were implementing insights from co-design, but making it clear in the survey that we didn’t just kind of come up with these questions out of nowhere, that these were co-designed with community and represent the different priorities of different language organisations, workers, and communities across Australia. So, we want the community to know why we’re asking these questions. And also, why they should answer the questions. Because ultimately, that’s why we’re asking the survey questions, because we want people to answer the questions.

Alex: Yeah, yeah, and I think that also comes through in the next part of the survey as well, which is about how languages can be better supported, which again gives a lot of, sort of co-designed ideas of different ways of support that people can then talk to and expand on, so that what comes through in your data, hopefully, is really community-led ideas of what government support or community support would look like, rather than top-down approaches.

So, for example, the survey asks about forms of government funding, reform to government infrastructure, access to what the survey calls ‘spaces for languages’. I really like this idea as a sociolinguist, I really get that. Access to language materials through community support. The survey also mentions legislation about languages as a possible form of support. So this should encourage policymakers not to intuit or impose solutions, but rather to listen to the survey language respondents and what they say they need.

What I especially noticed in this part of the survey was the question about racism affecting the strength of language. Or, if you like, reducing racism as a way of supporting language renewal. I don’t think this question was asked in previous versions of the survey, right? Can you tell us what led your team to include this one?

Zoe: Yeah, so, this idea of a supported language, as I measured… as I explained before, is one of the measures in, Outcome 16 of Closing the Gap, and that we want policymakers to listen to what the language communities want and need in regards of support, because, you know, in Australia, there’s so much language diversity, it’s not a one-size-fits-all approach. Funding was something that all language communities had in common, whether it was language revitalisation they needed funding for, resources and language workers, but also languages that, one could say are in maintenance, so languages considered strong languages, that have a lot of speakers, they also need funding to make sure that their language, isn’t at risk of being lost, and that, it can stay a strong language.

So, there are other kinds of ways that a language can be supported, and if we’re talking about, kind of racism and discrimination as a way that a language isn’t supported. It was important for us to kind of ask that question, because in co-design it was clear that racism and discrimination are still massively impacting language revitalisation and strengthening efforts. The unfortunate reality of the situation of Australian languages, Indigenous languages, is that due to colonisation, Indigenous languages have been actively suppressed.

We want to make sure that respondents of the survey have the opportunity to, kind of, participate in this truth-telling. It is an optional question. We understand it can be somewhat distressing to talk about language loss and the impacts of racism and things like that, but if respondents feel comfortable to answer this question, it does give communities the opportunity to share their stories about how their language has been impacted by racism. So, yeah.

Alex: I really think that’s important, not just to inform future policy, but the act of responding itself, as you say, is a form of truth-telling, and the act of asking, and having an institute that will then combine all those responses and tell other people. That’s an act of what we might call truth-listening, which is really important in confronting the social setting of language use and renewal. This goes back then, I guess, to strength. It’s not just how many people learn a language, or how many children exist who grow up in households speaking a language. There has to be a social world in which that language is not discriminated against, and those people don’t feel discriminated against for wanting to learn that language or wanting to use it.

Now, people may get the impression that language renewal is all hardship and bad news because of a focus on ‘language loss’, in quotes, or language ‘death’, or oppression. This pervades so much of the academic and media commentary. But you and I, Zoe, we met recently in person at a fabulous Indigenous-led conference in Darwin called PULiiMA and there, there were delegates from 196 Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander languages participating. So, that’s just one indication of the enormous effort and progress in this space around Australia, and mainly progress and effort initiated by language communities themselves, rather than governments.

So in that context, it’s important, I think, that this survey also has a section about languages flourishing, the positive focus. Languages are being learnt and taught and used and revived and loved. Tell us more about the design and purpose of the ‘flourishing’ sections of the survey.

Zoe: Yeah, I just want to say that how awesome PULiiMA was, and to see all the different communities all there, and there was so much language and love and support in the room, and everyone had a story to tell about how their language was flourishing, which was so awesome to hear. A flourishing language in terms of designing a survey and asking questions about, is a language flourishing, is a tricky thing to unpack, because in co-design, we kind of heard that a flourishing language can be put down to two things, and that’s visibility and growth of a language. And so growth of a language is something that you can understand, based off the questions that we’ve already asked, in kind of the strength of a language, how many speakers, is this number more or less compared to last time, the last survey? We’re also asking questions about, ‘has this number grown?’ in case it kind of sits within the same bracket as it did in the last survey.

And visibility is, kind of the other factor, which can be misleading sometimes as well. We’re asking questions about you know, is it being used in place names, public signage, films and media. Just to name a few. But a language that is highly visible in public maybe assumed to be strong, but isn’t strong where it matters, so, being used within families and communities. So, this section is a little bit smaller, because it kind of builds on the questions in previous sections.

It will be interesting to see, kind of, the idea of a flourishing language, and we do have the opportunity for people to kind of expand on their, responses in, kind of, long form answers, so people can explain, in their own words, in detail, if they choose to, kind of, how they see their language as being flourishing,

But, yeah, for a language to be strong and flourishing, it needs to be supported, and that’s something that was very clear in co-design, and people wanting things like language legislation, and funding, and how these things can be used to support the language strength, and to allow it to flourish. So in this section, we also have, kind of, an opportunity for people to give us their top 3 language goals. So whether that’s, they want to increase the number of speakers, or they want to improve community well-being. All sorts of different language goals and the opportunity for people to put their own language goals and the supports needed to achieve those language goals. So, the people who would benefit from the data from this survey, the government, policy makers, communities, they can see what community has actually said are their priorities for their language, and what they believe is the best way to address those language goals. So, encouraging self-determination, within this survey.

Alex: And following on from that point, I have a question in a second about, sort of, how you report the information, and also data sovereignty, how communities have access to, in a self-determined way, use this resource. But I just wanted to ask one more procedural question first. So, you shared a complete draft with me, and we’ve spoken about the redrafting process, so I know the survey’s close to ready, but where are you at the team at AIATIS is up to now – and now, actually, for those listening in the future, is October 2025. Do you have an idea of when it will be released for people to answer, and who will you be asking to answer this survey?

[brief muted interruption]Zoe: Yeah, so we’ve just hit a huge milestone in the research project where we’re in the middle of our ethics application. So, we’ve kind of finished drafting the survey, and it’s getting ready for review from the Ethics Committee at AIATSIS. And hopefully, if all goes well, we’ll be able to start rolling out the survey in November [2025].

So yes, it’s been a long time coming. This survey’s been in the works for many years. I’ve only personally been working on this project for a little under 12 months, but there have been many people before me working towards this milestone.

And the people that we want to be completing this survey are what we’re calling language respondents. So we don’t necessarily want every Indigenous person in Australia to talk about their language, but rather have one response per language by a language respondent who can kind of speak on the whole situation and status of their language, and can answer questions like how many speakers speak the language. So that could be anyone from an elder to a language centre staff member, maybe a teacher or staff member at a bilingual school. We’re not defining language respondent and who can be a language respondent because we understand that that’s different, depending on the language community, and if there are thousands of speakers of a language, or very few speakers of a language. We also understand that there could be multiple people within one language group that are considered language respondents, so we’re not limiting the survey to one response per language, but that’s kind of the underlying goal that we can get as many responses from the different languages in Australia, but at least one per language.

Alex: That makes sense. So, it’s sort of at least one per speaker group, or one per language community.

Zoe: Yeah.

Alex: Yep. Yeah. Yep. And then… so the questions I foreshadowed just before, one is about the reporting. So, I noticed last time around the National Indigenous Languages Report, which came out after the last survey – so the report came out in 2020 – that incorporated this really important idea of language ecologies, and that was one of the biggest innovations of that round of the survey. And that was, I think, directed at presenting the results in a way that better contextualized what support actually looks like on the ground, rather than this very abstracted notion of each language being very distinct and sort of just recorded in government metrics, but [rather] embedding it in a sense of lots of dynamic language practices, from people who use more than one variety.

So do you want to tell us a little bit more about how you’ve understood that language ecologies idea? Because I see that comes up in a question as well, this time around in the survey, and is it in the survey because you’re hoping to use that in the framing of the report as well?

Zoe: Yeah, so the third NILS, which produced the National Indigenous Languages Report in 2020, contributed massively to increasing awareness of language ecologies, and this idea that a language doesn’t exist within a bubble. It has contextual influences, particularly when it comes to multilingualism and other languages that incorporate, are incorporated into the community. So NILS4 aims to build on this work, in collecting interconnected data about what languages are being used. Who are they being used by? In what ways? Where are they being used at schools? At the shops, in the home. Different languages, as you mentioned before, different varieties of English, so that could be Aboriginal English, for example, or Standard Australian English. It could be other Indigenous, traditional Indigenous languages, so some communities are highly multilingual and can speak many different traditional languages. Some communities may use sign languages, whether that’s traditional sign languages or new sign languages, like Black Auslan. And kind of knowing how communities use not only the language that the survey is being responded to about, but also other languages, which will help with things like interpreting and translating services, education services, all sorts of different, things that, by understanding the language ecology better and the environment that the language exists in, yeah —

Alex: That makes sense, and there you’ve mentioned a few things that I didn’t really ask you about, but I’ll just flag they’re there in the survey too, translation and interpreting services, education, government services, and more broadly, workforce participation through a particular Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander language. That’s important data to collect. But the last sort of pressing question I have for you in this podcast is not about language work but about data sovereignty. This is a really big issue in Australia, not just for this survey, but for all research, by and with Indigenous peoples, and particularly looking at older research that was done without the involvement of Indigenous people, where there’s been problems with who controls and accesses data. So, what happens to the data that AIATSIS collects through this survey?

Zoe: Yeah, so data sovereignty is obviously one of our priorities and communities fundamentally will own the data that they input into the survey. And there will be different ways that, this information will be shared or published, depending on what the respondent consents to. So, part of the survey includes this consent form, where they basically, can decide how their data will be used and shared. And so the kind of three primary ways that the data will be used is: it will be sent to the Productivity Commission for Closing the Gap data, as I mentioned before, we have been funded in order to produce data for Closing the Gap Target 16, and so the data that’s sent to the Productivity Commission will be all de-identified. And this will be all the, kind of, quantitative responses, so nothing that can kind of be identified will be sent to the Productivity Commission. And this kind of data is kind of the baseline of what people are consenting to by participating in the survey. If they don’t consent to this, then, they don’t have to do the survey, their response won’t be recorded.

And then the other kind of two ways that AIATSIS will be reporting on the data is through the NILS4 report that will be published next year [2026], and also this kind of interactive dashboard on our website. So people will be able to kind of look at some of the responses. And communities will have the option on whether this data is identified or de-identified, so some communities may wish to have their responses identifiable, and people will be able to search through and see kind of data that relates to their communities, or communities of interest, or they might choose to kind of remain anonymous and de-identified, and so these are going to be mostly quantitative responses as well.

However, we are interested in, kind of publishing these case studies in the NILS report, which will be opportunities for communities to tell their language journey in their own words. And so this is a co-opt, sorry, an opt-in co-authored chapter in the NILS report, that, yeah, language communities can not just have data, or their responses, but have the context provided, the story of their language and their data. And that was something that was really evident in co-design, that the qualitative data needs to exist alongside the quantitative data, and that’s a huge part of data sovereignty as well, like, how communities want to be able to share their data. So, we’re really excited about this kind of, co-authored case study chapter in the report, because community are excited about it as well. They want to be able to tell their story in, in their own words.

And so, that’s kind of how the data will be used and published, but, there are other ways that the community will be able to kind of access their data that they provide in the survey. So, that’s also really important to us, and we’re following the kind of definitions of Indigenous data sovereignty from the Maiam Nayri Wingara data sovereignty principles. So, making sure that, yeah, community have ownership of their data, and they can have access to it, are able to interpret it, analyse it. And this is kind of being done from the beginning of co-design all the way up to the reporting, and that, yeah, community have control over their data at all points of this process.

Alex: It sounded like just such a thoughtfully managed and thoughtfully designed survey, so thanks again, Zoe, for talking us through it, and all the best for a successful rollout. The next phase should be really interesting for you to actually get people reading and responding, and I’ll be looking out for the survey results when you publish them later in 2026. Is there anything else about the survey that you’d like to tell our listeners?

Zoe: I think that we’ve had a really, productive conversation about our survey. We’re really excited to start rolling it out, and we’re really excited for people to look out for the results as they start to be published and shared next year. So, yeah, if anybody has any questions, or would like more information, I encourage everyone to kind of check out our website and send us an email. But yeah, thank you for having me, and for letting me chat about this project. It’s been a huge part of my life for the past few months, and excited for the rest of the world to get to experience this data, which is hopefully going to have such a big impact on communities having this accurate, reliable, comprehensive national database, that can be used for, yeah, major strides in Indigenous languages in Australia.

Alex: Well, we’ll definitely put the AIATSIS website, which is AIATSIS.gov.au, in the show notes, and then when the particular survey is out for people to respond to, we’ll put that in the notes on the Language on the Move blog that embeds this interview as well. And then people will be able to, as I understand it, respond online to the survey, or over the phone, or in person, and in a written form as well. So, as that information is available, we’ll share that with this interview.

So, for now, thanks so much again, Zoe, for talking me through this survey, and thanks everyone for listening. If you enjoyed the show, please subscribe to our channel, leave a 5-star review on your podcast app of choice, and of course, please recommend the Language on the Move podcast and our partner, The New Books Network, to your students, your colleagues, your friends. Speak to you next time!

Zoe: Thank you.

]]>In this episode, Brynn and Leah discuss a 2024 paper that Leah co-authored entitled “Language Access Systems Improvement initiative: impact on professional interpreter utilisation, a natural experiment”. The paper details a study that investigated two ways of improving the quality of clinical care for limited English proficiency (LEP) patients in English-dominant healthcare contexts, by:

- Certifying bilingual clinicians to use their non-English language skills directly with patients; and

- Simultaneously increasing easy access to professional interpreters by instituting on-demand remote video interpretation.

Brynn and Leah talk about the results of this study and what they mean for improved communication with LEP patients in healthcare.

If you liked this episode, be sure to say hello to Brynn and Language on the Move on Bluesky! Also support us by subscribing to the Language on the Move Podcast on your podcast app of choice, leaving a 5-star review, and recommending the Language on the Move Podcast and our partner the New Books Network to your students, colleagues, and friends.

References

A discussion about the terms “limited English proficiency” (LEP) and “non-English language preference” (NELP) in healthcare, which is also laid out nicely in Ortega et al.’s (2021) Rethinking the Term “Limited English Proficiency” to Improve Language-Appropriate Healthcare for All

Leung et al.’s (2025) paper entitled Partial language concordance in primary care communication: What is lost, what is gained, and how to optimize

And for more Language on the Move resources about the intersection between language and healthcare:

- Reducing Barriers to Language Assistance in Hospital

- Language policy at an abortion clinic

- Mismatched public health communication costs lives in Pakistan

- Why it’s important to use Indigenous languages in health communication

- Linguistic diversity in a time of crisis: Language challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic

Transcript (coming soon)

]]>To help our readers make sense of it all, we bring you a new occasional series devoted to the politics of language and migration.

Following on from Rosemary Salomone’s essay providing the historical and legal background, political anthropologist Gerald Roche today shows how the axing of language access service provision is an exercise in necropolitics – a use of power that leads to the suffering and death of certain groups of people.

***

On March 1st, 2025, President Donald Trump signed an executive order designating English as the official language of the United States of America. As a result, people are going to be harmed, and some will die.

There are direct and indirect reasons why this order will get people killed. Most directly, people will die as a result of this order because it will deny language access services to the more than 25 million people in the USA who need them. Apart from declaring English the USA’s official language, this order revokes Executive Order 13166 (August 11, 2000), which obliged US government agencies to provide language access services to people who need them.

Government agencies didn’t necessarily always fulfill their obligations under this order. But now, any motive they had to respect people’s language rights has been removed. Access to critical services will have life-threatening consequences in at least three arenas.

First, during natural disasters, such as fires, earthquakes, hurricanes, and floods, people require timely access to accurate information to have the best chance of survival. However, linguistic exclusion and discrimination are reproduced in how this information is provided to the public, resulting in what Shinya Uekusa calls ‘disaster linguicism’. Research during the recent LA wildfires by Melany De La Cruz-Viesca, showed that thousands of Asian Americans were denied access to disaster alerts and other information in their preferred language

Secondly, healthcare is another setting where language access is vital. When people’s language rights are respected in healthcare, they are more likely to use healthcare services, which are also more likely to be effective. When people’s language rights are violated, they are more likely to die in mass health incidents, such as pandemics. The individual consequences of linguistic exclusion can be seen in the case of Arquimedes Diaz, who called 911 after being shot, but was denied interpretation services for 10 minutes. Those crucial minutes were enough to leave him paralyzed. Any longer and he could have died.

A third area where people will be exposed to increased risk of death due to this executive order is the justice system. Sociolinguists such as Diana Eades, John Baugh, and many others have demonstrated that failures to account for linguistic differences lead to miscarriages of justice in police encounters, courtrooms, and elsewhere. This has life and death consequences particularly in the 27 states of the USA that still have the death penalty. However, we also need to take into account the fact that incarceration reduces life expectancy by 4 to 5 years, and that after incarceration, people experience twice the risk of death by suicide. Any miscarriage of justice on linguistic grounds that leads to imprisonment therefore has life and death consequences.

So, in disaster management, healthcare, and the justice system, the reduction or removal of language access services will directly expose people to harm and increased risk of death. There are also two additional, less direct ways that this order could lead to death.

First, we can look at the complex link between Trump’s official English order and death that particularly threatens Indigenous people. Trump’s order is almost certainly inspired by a law previously drafted by his vice-president, JD Vance: the English Language Unit Act of 2023. That proposed law included a clause stating that it could not limit Native Alaskan or Native American peoples’ use or preservation of their languages. The new order contains no such clause.

To understand why this is a problem and how it relates to death, we need to look more broadly at Trump’s record on Indigenous policy. During his first term, Trump carried out ‘continuous attacks’ on Indigenous communities, starting with a memo that reinstated construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline. Starting his second term, Trump signalled his hostility to Indigenous languages by using one of his first executive orders to wipe an Indigenous place name (Mount Denali) from the map. This prior hostility towards Indigenous communities, and Trump’s general austerity agenda, mean that Indigenous languages are likely to be underfunded during his second term. This will have life and death consequences, because decades of research has shown that language revitalization has health benefits, improves wellbeing, and reduces suicide rates.

Finally, Trump’s promotion of English and his hostility towards Indigenous peoples and languages should be viewed as part of a broader white supremacist agenda that has life and death implications for people of color. The push to make English the official language of the USA has always involved opposition to bilingualism, and often to specific languages: Jane Hill has noted how English-only movements often go hand-in-hand with efforts to limit the use and legitimacy of Spanish. These movements have gathered steam since the 1980s, and have consistently been associated with the right, and its more xenophobic, white-supremacist fringes: the linguistic fascists, as Geoffrey Pullum once memorably dubbed them.

Trump’s executive order effectively mainstreams the far-right linking of whiteness, English, and belonging in the USA. Asao Inoue has argued that the life-and-death consequences of this linkage start with the discursive circuits and communicative practices that shape judgments about whose language and life are considered valuable. But more directly, this order will legitimize the white supremacist practice of using perceived proficiency in English to target people for violence. We saw this in December 2024 in New York City when one person was killed, and another injured, after their attacker asked them if they spoke English. In another incident in July 2024, a man shot seven members of a family after telling them to “speak English” and “go back where they came from.” Trump’s official English order risks inciting similar acts of violence.

Taking all of this together, we can see that Trump’s executive order making English the official language of the USA will almost certainly harm people, and is also likely to lead to deaths. That’s why I think we need to take what I call a necropolitical approach to language – one that examines how language, death, and power intersect. A necropolitical approach demonstrates that designating English as the USA’s official language is not just a symbolic declaration, it is also, for some people, a death sentence.

Related content

In this episode of the Language-on-the-Move Podcast, Gerald Roche talks with Tazin Abdullah about his new book The Politics of Language Oppression in Tibet. Gerald is also a regular contributor to Language on the Move and you can read more of his work here.

For more content related to multilingualism in crisis communication, head over to the Language-on-the-Move Covid-19 Archives.

]]>

The White House (Image credit: Zach Rudisin, Wikipedia)

Editor’s note: The Trump administration has recently declared English the official language of the USA while simultaneously cutting the provision of English language education services. This politicization of language and migration in the USA is being felt around the world.

To help our readers make sense of it all, we bring you a new occasional series devoted to the politics of language and migration.

We start with an essay by Professor Rosemary Salomone, the Kenneth Wang Professor of Law at St. John’s University in New York City. Professor Salomone, an expert in Constitutional and Administrative Law, shows that longstanding efforts to make English the official language of the USA have always been “a solution in search of a problem.”

***

English in the Crossfire of US Immigration: A Solution in Search of a Problem

Rosemary Salomone

Making English the official language of the US has once again reared its head, as it does periodically. This time it has gained legal footing in a novel and troubling way. It also bears more serious implications for American identity, democracy and justice than the unaware eye might see and that the country should not ignore.

Trump Executive Order

Amid a barrage of mandates, the Trump Administration has issued an executive order that unilaterally declares English the “official language” of the United States. It does not stop there. It also revokes a Clinton Administration executive order, operating for the past 25 years, that required language services for individuals who were not proficient in English.

The order briefly caught the attention of the media in a fast-paced news cycle. Yet its potentially wide-sweeping scope demands more thorough scrutiny and reflection for what it says and what it suggests about national identity, shared values, the democratic process and the role of language in a country with long immigrant roots. It also calls for vigilance that this is not a harbinger of more direct assaults to come on language rights. Subsequent reports of closing Department of Education offices in charge of bilingual education programs and foreign language studies clearly signal a move in that direction.

English and National Identity

English has been the de facto official language of the United States for the past 250 years despite successive waves of immigration. Though the nation’s Founders were familiar with the worldview taking hold in Europe equating language and national identity, they also understood that they were embarking on a unique nation-building project grounded in a set of democratic ideals. As a “settler country” those shared ideals and not the English language have defined the US as a nation unlike France, for example, where the French language became intertwined with being a “citoyen” of the Republic.

In the early days of the American republic, the national government issued many official texts in French and German to accommodate new immigrants. Languages were also woven less officially into political life. Within days of the adoption of the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, a newspaper in Pennsylvania published a German translation to engage the large German speaking population in support of the independence movement. As John Marshall, the fourth chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, noted in a letter to Noah Webster in 1831, geographic and social mobility, rather than public laws, would create “an identity of language through[out] the United States.” And so it has been.

The executive order distinguishes between a “national” and an “official” language. English has functioned well as the national language in government, the courts, schooling, the media and business. It has evolved that way through a maze of customs, institutions and policies that legitimize English throughout public life. It is the language spoken by most Americans. Over three-quarters (78.6 percent) of the population age five and older speaks English at home while only 8.3 percent speaks English “less than very well.” And so, by reasonable accounts, formally declaring it the official language after 250 years seems to be a solution without a problem unless the problem is immigration itself and unwarranted fears over national identity.

While benign on its face, at best the Trump order veers toward nationalism cloaked in the language of unity and efficiency. At worst it’s a thinly veiled expression of racism and xenophobia, narrowly shaping the collective sense of what it means to be American. Though less extreme in scope, its spirit conjures up uniform language laws in past autocratic regimes where language was weaponized against minority language speakers. Think of Spain under Franco and Italy under Mussolini where regional languages were outlawed.

Context and Timing

Context and timing matter. The order comes on the heels of the Trump Administration’s shutting down, within an eye-blink of the inauguration, the Spanish-language version of the White House website along with presidential accounts on social media. Reinstated throughout the Biden years, the website had first been removed in 2017 during the first Trump Administration.

During the 2016 presidential campaign, Trump blasted former Florida governor Jeb Bush, who is married to a Mexican-American, for speaking Spanish on the campaign trail. “He should really set the example by speaking English while in the United States,” Trump remarked, projecting what became an administration openly hostile to “foreigners” and the languages they speak. Against that history, the official English order now signals rejection of the nation’s large Spanish-speaking population and the anti-immigrant feelings their growing numbers have engendered.

The irony is that Trump, not unlike other politicians, has courted that population with Spanish language ads. With 58 million people in the United States speaking Spanish, political operatives understand that Spanish is the “language of politics.” But the “politics of language” is far more complicated. The 2024 Trump campaign ad repeating the words, “Que mala Kamala eres” (“How bad Kamala you are’) to the tune of a famous salsa song with the image of Trump dancing on the screen is hard to reconcile with his prior and subsequent actions as president.

The current shutdown of the Spanish-language website did not go unnoticed among public dignitaries in Spain. King Felipe VI described it as “striking.” The president of the Instituto Cervantes, poet Luis Garcia Montero, called it a “humiliating” decision and took exception to Trump’s “arrogance” towards the Hispanic community. On the domestic front, the executive order raised even more pointed concerns among immigrant and Hispanic groups in the United States.

Issued at a time of mass deportations, hyperbolic charges of immigrant criminality, attacks on “sanctuary” cities and states, and rising opposition to immigration in general, the new executive order will further divide rather than unite an already fractured nation. Fanning the flames of hostility toward anyone with a hint of foreignness, it can incite lasting feelings of inclusion and exclusion that cannot easily be undone.

Official Language Movement

The Trump order did not come from out of the blue. It is the product of years of advocacy at the federal and state levels promoting English to the exclusion of other languages. Proposals to make English the nation’s official language have been floating through Congress since 1981 when the late Senator Samuel I. Hayakawa (R. CA), a Canadian-born semanticist and former college president, introduced the English Language Amendment. Though the joint resolution died, it set a pattern for congressional proposals, some less draconian, all of which have stalled. The most recent attempt was in 2023 when then Senator J.D. Vance (R. Ohio) introduced the English Language Unity Act.

Hayakawa went on to form “U.S. English” in 1983. It calls itself the “largest non-partisan action group dedicated to preserving the unifying role of the English language in the United States.” It currently counts two million members nationwide. In 1986, its then executive director Gerda Bikales tellingly warned, “If anyone has to feel strange, it’s got to be the immigrant, until he learns English.”

The group’s website now celebrates the Trump order as “a tremendous step in the right direction,” a supposed antidote to the 350 languages spoken in the United States. Obviously that level of diversity can also be viewed as a positive unless “diversity” is totally ruled out of even the lexicon. Two other advocacy groups with similar missions subsequently joined the movement: English First and Pro English.

Defying Democratic Norms

The fruits of those efforts can be found in official English measures in 32 states. The earliest, from Nebraska, dates from 1920 in the wake of World War I when suspicion of foreigners and their languages reached unprecedented heights. By 1923, 23 states had passed laws mandating English as the sole language of instruction in public schools, some in private schools as well. With immigration quotas of the 1920s (lifted in the mid-1960s) diluting the “immigrant threat,” the official English movement didn’t seriously pick up again until the 1980s as the Spanish-speaking population grew more visible. The remaining Official English laws were largely adopted through the 2000s, the last in 2016 in West Virginia. Some of them, as in California and Arizona, were tied to popular backlash against public school bilingual programs serving Spanish-speaking children.

Some of these state laws were passed by a voter approved ballot measure, others by the state legislature. Some reside in the state constitution, others in state statutory law. Unlike the Trump order mandated by executive fiat, they all underwent wide discussion by the people or their elected representatives, which a measure of such high importance, especially with national reach, demands. And they can only be removed using a similar process, unlike an executive order subject to change by the mere stroke of a future presidential pen. This is not like naming the official state flower or bird, a mere gesture. The consequences are far more serious.

As official English supporters are quick to point out, upwards of 180 countries also have official languages, some more than one. Standing alone, that argument sounds convincing. In well-functioning democracies, however, those pronouncements are carved into the nation’s constitution from the beginning or by subsequent amendment, or they’ve been adopted by the national legislature, again through democratic deliberation. At times they’ve been triggered by a particular event. France added the French language to its constitution in 1992 for fear that English would threaten French national identity with the signing of the Maastricht Treaty creating the European Union. Exactly what is triggering the current move in the United States? The answer is quite transparent. It’s immigration.

As official English supporters are quick to point out, upwards of 180 countries also have official languages, some more than one. Standing alone, that argument sounds convincing. In well-functioning democracies, however, those pronouncements are carved into the nation’s constitution from the beginning or by subsequent amendment, or they’ve been adopted by the national legislature, again through democratic deliberation. At times they’ve been triggered by a particular event. France added the French language to its constitution in 1992 for fear that English would threaten French national identity with the signing of the Maastricht Treaty creating the European Union. Exactly what is triggering the current move in the United States? The answer is quite transparent. It’s immigration.

Some countries, like Brazil and the Philippines, allow for regional languages. Other approaches are less formalized. In the Netherlands and Germany, the official language operates through the country’s administrative law. In Italy, though the Italian language is not officially recognized in the constitution, the courts have inferred constitutional status from protections expressly afforded linguistic minorities. Other countries, including the United Kingdom, Mexico, Australia and Argentina, the latter two also “settler countries,” recognize a de facto official language as the United States has done since its beginning.

Clinton Order Protections

While the official English declaration might mistakenly pass for mere symbolism, the revocation of the Clinton order quickly turns that notion on its head. Rather than “reinforce shared national values,” as the Trump order claims, revoking the Clinton order protections undermines a fundamental commitment to equal opportunity and dignity grounded in the Constitution and in Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. From that Act and its regulations prohibiting discrimination on the basis of national origin, the Clinton Administration drew its authority, including using national origin as a proxy for language, to protect language rights. In an insidious twist, the Trump executive order uses language as a proxy for national origin, i.e. immigrant status, to pull back on those same protections.

The Clinton order, together with guidance documents issued by the Department of Justice, required federal agencies and other programs that receive federal funds to take “reasonable steps” to provide “meaningful access” to “information and services” for individuals who are not proficient in English. As advocates argue, removing those requirements opens the door for federal agencies and recipients of federal funds, including state and local governments, to deny critical language supports that assure access to medical treatment, social welfare services, education, voting rights, disaster relief, legal representation and even citizenship. In a virtual world of rampant disinformation, it is all the more essential that governments provide non-English speakers with information in emergencies, whether it’s the availability of vaccines during a flu pandemic or the need to evacuate during a flood or wildfire, as well as the facts they ordinarily need to participate in civil life.

With current cutbacks in federal agency funding and staff, rising hostility toward immigrants, and the erosion of civil rights enforcement, one can reasonably foresee backsliding on any of those counts. One need only look at the current state of voting and reproductive rights to figure out where language supports may be heading when left to state discretion with no federal ropes to rein it in.

Multilingualism for All

The Trump order overlooks mounting evidence on the value of multilingualism for individuals and for the national economy. Language skills enhance employment opportunities and mobility for workers. Multilingual workers permit businesses to compete both locally and internationally for goods and services in an expanding global market

It takes us back to a time not so long ago when speaking a language other than English, except for the elite, was considered a deficit and not a personal asset and national resource. It belies both the multilingual richness of the United States and the fact that today’s immigrants are eager to learn English but with sufficient time, opportunity and support. They well understand its importance for upward mobility for themselves and for their children. That fact is self-evident. With English fast becoming the dominant lingua franca globally, parents worldwide are clamoring for schools to add English to their children’s language repertoire and even paying out-of-pocket for private lessons.

Rather than issuing a flawed pronouncement on “official English,” the federal government would better spend its resources on adopting a comprehensive language policy that includes funding English language programs for all newcomers, along with trained translators and interpreters for critical services and civic participation, while supporting schools in developing bilingual literacy in their children. Today’s “American dream” should not preclude dreaming in more than one language. In fact, it should affirmatively encourage it for all.

In the meantime, the Trump order promises to provoke yet more litigation challenging denials in services under Title VI and the Constitution, burdening the overtaxed resources of immigrant advocacy groups and of the courts. Worst of all, it threatens to inflict irreparable harm on thousands of individuals and families struggling to build a new life while maintaining an important piece of the old.

It’s not the English language or national identity that need to be saved. It’s the democratic process, sense of justice and clear-eyed understanding of public policy now threatened by government acts like the official English executive order.

Related content

In this episode of the Language on the Move Podcast, Rosemary Salomone chats with Ingrid Piller about her book The Rise of English.

]]>Tazin and Jia discuss crisis communication in a linguistically diverse world and a new book co-edited by Dr. Jia Li and Dr. Jie Zhang called Multilingual Crisis Communication that gives us insights into the lived experiences of linguistic minorities affected during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Multilingual Crisis Communication is the first book to explore the lived experiences of linguistic minorities in crisis-affected settings in the Global South, particularly during the Covid-19 pandemic. China has been selected as a case of inquiry for multilingual crisis communication because of its high level of linguistic diversity. Taking up critical sociopolitical approaches, this book conceptualizes multilingual crisis communication from three dimensions: identifying communication barriers, engaging communication repertoires, and empowering communication justice.

Comprising eight main chapters, along with an introduction and an epilogue, this edited book is divided into three parts in terms of the demographic and social conditions of linguistic minorities, as indigenous, migrant, and those with communicative disabilities. This book brings together a range of critical perspectives of sociolinguistic scholars, language teachers, and public health workers. Each team of authors includes at least one member of the research community with many years of field work experience, and some of them belong to ethnic minorities. These studies can generate new insights for enhancing the accessibility and effectiveness of multilingual crisis communication.

This book will be of interest to academics and postgraduate students in the fields of multilingualism, intercultural communication, translation and interpreting studies, and public health policy.

This volume brings together 23 contributors and covers a range contexts in which crisis communication during the COVID19 pandemic has been investigated. Focusing on China owing to a high level of linguistic diversity, this book uses critical sociopolitical approaches, to identifying communication barriers, engaging communication repertoires, and empowering communication justice.

This volume brings together 23 contributors and covers a range contexts in which crisis communication during the COVID19 pandemic has been investigated. Focusing on China owing to a high level of linguistic diversity, this book uses critical sociopolitical approaches, to identifying communication barriers, engaging communication repertoires, and empowering communication justice.

Advance praise for the book

‘Setting a milestone in critical sociolinguistic and applied linguistic studies, this volume offers critical insights into overcoming communication barriers for linguistic minorities during crises, promoting social justice, and enhancing public health responses through inclusive, multimodal, and multilingual strategies. It also serves as testimonies of resilience, courage and kindness during the turbulent time’ (Professor Zhu Hua, Fellow of Academy of Social Sciences and Director of International Centre for Intercultural Studies, UCL, UK)

‘The global pandemic has brought to the fore the key role of multilingual communication in disasters and emergencies. This volume contains cutting edge ethnographic studies that address this seriously from the perspective of Chinese scholars and minoritized populations in China. A decisive contribution to the burgeoning field of multilingualism and critical sociolinguistics in times of crisis.’ (Professor Virginia Zavala, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, Perú)

Related content

For related content, visit the Language on the Move Covid-19 Archives.

Transcript (coming soon)

]]>

NSW Police (Image credit: Edwina Pickles, SMH)

Editor’s note: The Language on the Move team closely collaborates with the Law and Linguistics Interdisciplinary Researchers’ Network (LLIRN). To raise awareness of LLIRN and feature the research of its members, we are starting a new series about exciting new research in specific areas of language and law.

In this first post in the series, LLIRN founders and conveners Dr Alex Grey and Dr Laura Smith-Khan introduce the research of three early career researchers working on language, policing, and criminal justice.

***

Alex Grey and Laura Smith-Khan

***

The Law and Linguistics Interdisciplinary Researchers’ Network (LLIRN) came into being in 2019, after an initial symposium involving a group of academics and students, mainly from Australian universities, whose research is interested in the various intersections of language and law. One of our key goals of the symposium was to learn more about each other’s work and create new opportunities to collaborate.

Since then, LLIRN has grown and we have organized and run a number of different initiatives, including multiple panels at conferences across both linguistics and law, a special issue that showcased the work of several of our (mainly early career) members, and a lively and growing mailing list.

Fast forward to 2024, our Listserv now includes members from at least 37 different countries, at diverse stages of their careers, working as academics, as language or legal professionals, and/or in policy or decision-making roles. However, as LLIRN convenors, we have felt that we still have much to learn about the members who make up the network, the expertise they have and their goals. This new blog series intends to address this gap: we want to learn (or “LLIRN”) more about each other, and to make our learning public so that others too can learn more about us.