I have always been fascinated by the human voice. When you speak on the phone with a stranger, it can reveal so much about them. You can often tell whether it’s a man or a woman, estimate their age, and sense their attitudes and emotional state — whether they sound polite, distant, nervous, happy, or sad.

And, importantly, you can almost immediately recognize whether the person speaking has a foreign accent or not. Pronunciation is never just about sounds: it reflects the social meanings attached to language.

A different kind of accent training

In my phonetics and phonology classes, I usually deal with a familiar scenario: students ask me how they can improve their pronunciation in their L2 Italian or L2 Spanish and sound more “natural”. How to avoid a foreign accent — or at least minimize it.

Of course, there is nothing wrong with having a foreign accent. It simply shows that you grew up speaking another language. But many students want to refine their pronunciation, and I am a happy companion on that journey.

This time, however, it was different. A friend asked me to do a favor for one of her friends — an actress. In her new movie production, she had to play a German woman speaking Spanish with a strong German accent.

She told me: “Well, I know I have to do the German R sound, which is very different from Spanish. But I feel there’s more.”

Exactly. There are even native Spanish speakers who have difficulty pronouncing the rolled R — this phenomenon has a name: «rhotacism» or «the French R» (la erre francesa). But even speakers who don’t “roll” the R can still sound perfectly native-like.

(Image credit: Andrea Pešková)

So, what is it all about?

What makes Spanish sound German

Let’s take a closer look at some of the most distinctive features of “German” Spanish.

German speakers don’t only struggle with R sounds. One of the most noticeable characteristics is the aspiration of the voiceless stops /p t k/: pala ‘shovel’ may sound like [ˈphala], tono ‘tone’ like [ˈthono], and cosa ‘thing’ like [ˈkhosa]. The aspiration should remain subtle and light — otherwise it may begin to sound more “English” than “German”.

Another typical feature is that the final [o] may sound overly close, almost like [u], turning perro ‘dog’ or loco ‘crazy’ into perru or locu in Spanish ears.

German speakers also tend to pronounce the Spanish approximants [β ð ɣ] between vowels as full stops, so la bodega ‘the wine cellar’ [laβoˈðeɣa] becomes something like [laboˈdeɡa] rather than the softer Spanish version.

They also often insert a glottal stop before vowel-initial syllables or words. El auto ‘the car’ becomes [elˈʔawto], and otra ‘other’ turns into [ˈʔotɾa]. This gives Spanish a slightly “choppy”, segmented rhythm.

Orthographic influence plays its role too. Speakers may pronounce the normally silent h, voice the s between vowels as z (casa ‘house’ [ˈkaza]), or mispronounce <eu> as [ɔɪ̯] instead of [ew]. And the infinitive ending -er may shift towards something like -a in the word comer [komˈea] ‘to eat’.

Prosody contributes as well. Stressed open syllables may sound unusually long, unstressed vowels may be reduced, stress placement may shift, and intonation patterns often diverge. For example, the end of neutral statements may sound exaggeratedly emphasized, lacking the subtle falling contour typical of Spanish.

Making the accent sound real

We worked on all these phonetic features, and my student did an excellent job. We wanted the accent to sound authentic and recognizable, but never exaggerated or comical.

While we focused mainly on pronunciation, I also pointed out that in real-life speech, grammatical transfer phenomena often accompany a foreign accent. In many movies, accented speech is portrayed with perfect grammar but an overdone pronunciation, which feels unnatural.

In reality, small deviations are common in second-language speech — for instance, occasional omission of articles (Me gusta pizza ‘I like pizza’ instead of Me gusta la pizza ‘I like the pizza’), overuse of subject pronouns that are usually dropped in Spanish, or transfer of verbal tense and aspect.

These subtle grammatical influences, combined with pronunciation, shape the overall impression of an accent and make speech sound more believable.

From correction to creation

What we both found most fascinating in this experience was the shift in perspective: instead of trying to eliminate a foreign accent, we tried to recreate one. It was a playful reminder that accents are not errors but expressions of our identity, multilingual experience and authenticity.

We often see how accent becomes a marker of belonging — or of difference.

But when we learn to listen closely, every accent tells a fascinating story about who we are, where we come from, and the paths our languages have taken.

Additional resources

If you want to explore more accents in Spanish, visit this page that my students in Osnabrück (Germany) created: https://andrea-peskova.com/archivo-de-los-acentos-l2/. There you will find examples of Czech, Italian, Slovak, Greek, and American English accents in Spanish.

]]>Have you ever listened to a language you don’t know and thought you recognized a word—only to realize later that you were completely mistaken? Our ears play tricks on us.

A while ago, I ran a small experiment with my German students. I played them two short sentences in Czech, my native language, and asked them to transcribe what they heard. The results were fascinating.

For example, about 90% of the forty students wrote down the Czech word malí [maliː] ‘small’ as mani [maniː]. To me, this seems puzzling—there is no n in the word! But for my students, the Czech l-sound somehow resembled the German n-sound. None of the Czech speakers I consulted ever had this impression.

This little classroom experiment shows something important: we don’t all hear sounds the same way. Our ears—or better said, our brains—are tuned by the language(s) we grow up with.

Why do we hear differently?

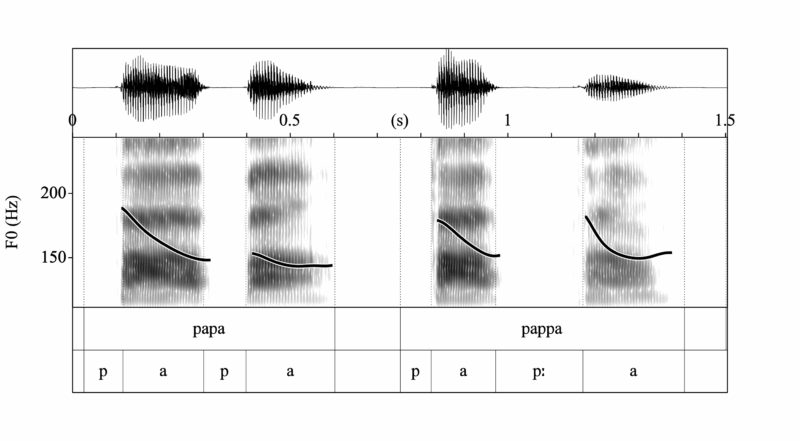

Image 1: Oscillogram and spectrogram of the Italian words papa ‘Pope’ and pappa ‘porridge’

Long before we speak, we are already great language users. Research shows that newborn babies can already distinguish speech sounds from noises. Even more surprisingly, they are able to recognize the rhythm of their native language from a non-native one before birth.

After birth, infants are surrounded daily by an enormous amount of speech input. Step by step, they build categories for the sounds of their native language. Up until around 8 to 12 months they can distinguish nearly all of the world’s speech sounds, even those that never appear in their environment.

A Japanese baby, for example, can hear the difference between r and l just as well as American or German babies can. But this ability does not last. As children grow, their brains focus on the categories that matter in their own language and ignore the rest—like the difference between r and l. This is why many Japanese adults often find it notoriously difficult to distinguish the two consonants in languages like English. What was once easy for the baby can become very challenging for the adult.

We perceive foreign languages through native filters

Learning the sound system of a language doesn’t stop with vowels and consonants. It also includes rhythm and intonation. And even for individual sounds like a or o, it’s not only about how you articulate them but also how long you hold them. This brings us to segmental quantity, or length. It refers to the use of duration (short vs. long) of vowels or consonants to distinguish lexical meaning. Quantity shows remarkable cross-linguistic variation.

The case of long consonants in Italian

Image 2: Soundproof cabins at the Free University of Berlin (left) and University of Helsinki (right)

What feels natural in one language may not exist in another. Take Italian. It belongs to just 3.3% of the world’s languages that distinguish short from long consonants (Ladefoged & Maddieson 1996).

This contrast appears in more than 1,800 Italian words, such as papa /ˈpapa/ ‘Pope’ versus pappa /ˈpapːa/ ‘porridge’ (Image 1). To be understood and to speak well, learners must get long consonants (called geminates) right—although it can be very challenging (e.g., Altmann et al. 2012).

Cross-linguistic differences in learners

In our project “Production and perception of geminate consonants in Italian as a foreign language”, we examine how Czech, Finnish, German, and Spanish learners acquire this feature.

The selection of these languages is not random. They all handle consonant length differently. German, for example, has no consonant length but contrasts short and long vowels in stressed syllables (e.g., Stadt [ʃtat] ‘city’ vs. Staat [ʃtaːt] ‘state’). Czech, like German, distinguishes vowel length, but unlike German, it does so in both stressed and unstressed syllables (e.g., nosí [ˈnosiː] ‘(s/he) carries’ vs. nosy [ˈnosɪ] ‘noses’). Finnish is the most similar to Italian, since it has both vowel and consonant length (e.g., muta [ˈmutɑ] ‘mud’ vs. mutta [ˈmutːɑ] ‘but’). And finally, Spanish has no length contrasts at all.

This diversity allows us to test how a learner’s native language shapes the way they hear and produce length in Italian.

How good are learners at perceiving length in Italian?

In a laboratory setting (Image 2) and by means of a perception experiment, we tested and compared 20 Czech, 20 Finnish, 20 German, and 20 Spanish learners of Italian.

We used 45 short nonsense words that followed Italian spelling and sound rules but had no meaning. Each word had two versions, differing only in whether a consonant was short or long (e.g., sàpolo vs. sàppolo; milèta vs. millèta).

The words covered different consonants and stress positions and were recorded by a native Italian speaker. In every trial, participants had to answer the question: “Does the audio pair you hear belong to the same or different word?”

What we found

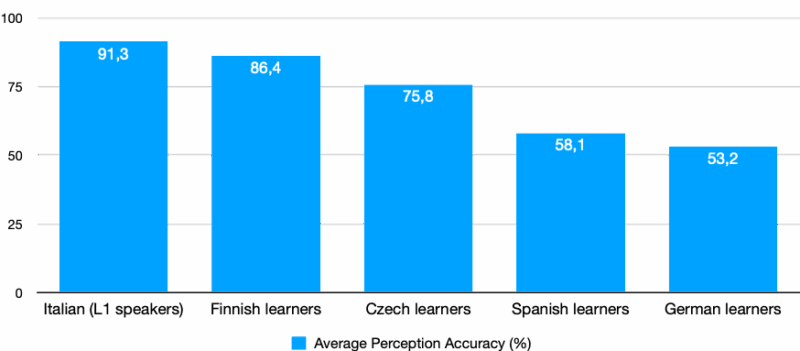

Image 3: Learner accuracy in perceiving Italian consonant length in comparison to native listeners

First language has great impact! Finnish learners, whose native system is closest to Italian, were the most accurate in hearing the difference between short and long consonants.

Czech learners followed, while German and Spanish learners struggled more (Image 3). Other factors also played a role. Learners heard contrasts more easily when the crucial sound appeared in stressed syllables, and some consonants were easier to notice than others.

Proficiency helped too—advanced learners did much better than beginners.

However, it is unexpected that the German group scored lower than the Spanish group—sometimes research simply surprises us!

Many factors could explain this, since every learner has their own story. Things like previous language experience, weekly study time, exposure to Italian, time spent in Italy, Italian friends, motivation, and personal talent can all play a role.

In our case, German learners had spent fewer hours per week learning Italian and had less experience studying or staying in Italy. Immersion—the experience of being surrounded by a language in real-life settings—seems a plausible factor behind their performance.

Why perception matters in language learning?

Why does pappa sometimes turn into papa in the ears of Italian learners? Because we all hear foreign languages through the features we are familiar with.

Our experiment showed that perception is difficult—but it can be improved. The key is to notice what is different and to train your ears. This means: Pronunciation training must start with perception (e.g., Colantoni et al. 2021).

In the end, learning a language is not just about new words—it’s about learning to hear differently.

References

Altmann, H.; Berger, I., & B. Braun (2012). Asymmetries in the perception of non-native consonantal and vocalic contrasts. Second Language Research 28(4), 387–413.

Colantoni, L., Escudero, P., Marrero-Aguiar, V., & J. Steele (2021). Evidence-based design principles for Spanish pronunciation teaching. Frontiers in Communication, 6, 639889.

Ladefoged, P., & I. Maddieson (1996). The sounds of the world’s languages. Oxford: Blackwell.

Acknowledgement

This blog post was written as part of the DFG-project “Production and perception of geminate consonants in Italian as a foreign language: Czech, Finnish, German and Spanish learners in contrast”, funded by the German Research Foundation (Project number 521229214) and executed at the Free University of Berlin. Project website: https://italiangeminates-project.com/

]]>

The White House (Image credit: Zach Rudisin, Wikipedia)

Editor’s note: The Trump administration has recently declared English the official language of the USA while simultaneously cutting the provision of English language education services. This politicization of language and migration in the USA is being felt around the world.

To help our readers make sense of it all, we bring you a new occasional series devoted to the politics of language and migration.

We start with an essay by Professor Rosemary Salomone, the Kenneth Wang Professor of Law at St. John’s University in New York City. Professor Salomone, an expert in Constitutional and Administrative Law, shows that longstanding efforts to make English the official language of the USA have always been “a solution in search of a problem.”

***

English in the Crossfire of US Immigration: A Solution in Search of a Problem

Rosemary Salomone

Making English the official language of the US has once again reared its head, as it does periodically. This time it has gained legal footing in a novel and troubling way. It also bears more serious implications for American identity, democracy and justice than the unaware eye might see and that the country should not ignore.

Trump Executive Order

Amid a barrage of mandates, the Trump Administration has issued an executive order that unilaterally declares English the “official language” of the United States. It does not stop there. It also revokes a Clinton Administration executive order, operating for the past 25 years, that required language services for individuals who were not proficient in English.

The order briefly caught the attention of the media in a fast-paced news cycle. Yet its potentially wide-sweeping scope demands more thorough scrutiny and reflection for what it says and what it suggests about national identity, shared values, the democratic process and the role of language in a country with long immigrant roots. It also calls for vigilance that this is not a harbinger of more direct assaults to come on language rights. Subsequent reports of closing Department of Education offices in charge of bilingual education programs and foreign language studies clearly signal a move in that direction.

English and National Identity

English has been the de facto official language of the United States for the past 250 years despite successive waves of immigration. Though the nation’s Founders were familiar with the worldview taking hold in Europe equating language and national identity, they also understood that they were embarking on a unique nation-building project grounded in a set of democratic ideals. As a “settler country” those shared ideals and not the English language have defined the US as a nation unlike France, for example, where the French language became intertwined with being a “citoyen” of the Republic.

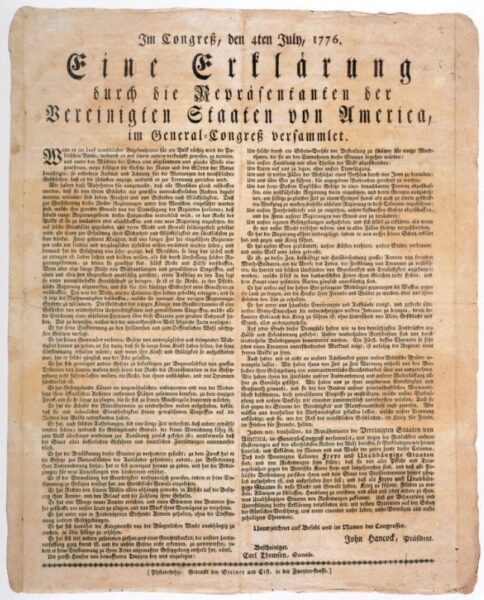

In the early days of the American republic, the national government issued many official texts in French and German to accommodate new immigrants. Languages were also woven less officially into political life. Within days of the adoption of the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, a newspaper in Pennsylvania published a German translation to engage the large German speaking population in support of the independence movement. As John Marshall, the fourth chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, noted in a letter to Noah Webster in 1831, geographic and social mobility, rather than public laws, would create “an identity of language through[out] the United States.” And so it has been.

The executive order distinguishes between a “national” and an “official” language. English has functioned well as the national language in government, the courts, schooling, the media and business. It has evolved that way through a maze of customs, institutions and policies that legitimize English throughout public life. It is the language spoken by most Americans. Over three-quarters (78.6 percent) of the population age five and older speaks English at home while only 8.3 percent speaks English “less than very well.” And so, by reasonable accounts, formally declaring it the official language after 250 years seems to be a solution without a problem unless the problem is immigration itself and unwarranted fears over national identity.

While benign on its face, at best the Trump order veers toward nationalism cloaked in the language of unity and efficiency. At worst it’s a thinly veiled expression of racism and xenophobia, narrowly shaping the collective sense of what it means to be American. Though less extreme in scope, its spirit conjures up uniform language laws in past autocratic regimes where language was weaponized against minority language speakers. Think of Spain under Franco and Italy under Mussolini where regional languages were outlawed.

Context and Timing

Context and timing matter. The order comes on the heels of the Trump Administration’s shutting down, within an eye-blink of the inauguration, the Spanish-language version of the White House website along with presidential accounts on social media. Reinstated throughout the Biden years, the website had first been removed in 2017 during the first Trump Administration.

During the 2016 presidential campaign, Trump blasted former Florida governor Jeb Bush, who is married to a Mexican-American, for speaking Spanish on the campaign trail. “He should really set the example by speaking English while in the United States,” Trump remarked, projecting what became an administration openly hostile to “foreigners” and the languages they speak. Against that history, the official English order now signals rejection of the nation’s large Spanish-speaking population and the anti-immigrant feelings their growing numbers have engendered.

The irony is that Trump, not unlike other politicians, has courted that population with Spanish language ads. With 58 million people in the United States speaking Spanish, political operatives understand that Spanish is the “language of politics.” But the “politics of language” is far more complicated. The 2024 Trump campaign ad repeating the words, “Que mala Kamala eres” (“How bad Kamala you are’) to the tune of a famous salsa song with the image of Trump dancing on the screen is hard to reconcile with his prior and subsequent actions as president.

The current shutdown of the Spanish-language website did not go unnoticed among public dignitaries in Spain. King Felipe VI described it as “striking.” The president of the Instituto Cervantes, poet Luis Garcia Montero, called it a “humiliating” decision and took exception to Trump’s “arrogance” towards the Hispanic community. On the domestic front, the executive order raised even more pointed concerns among immigrant and Hispanic groups in the United States.

Issued at a time of mass deportations, hyperbolic charges of immigrant criminality, attacks on “sanctuary” cities and states, and rising opposition to immigration in general, the new executive order will further divide rather than unite an already fractured nation. Fanning the flames of hostility toward anyone with a hint of foreignness, it can incite lasting feelings of inclusion and exclusion that cannot easily be undone.

Official Language Movement

The Trump order did not come from out of the blue. It is the product of years of advocacy at the federal and state levels promoting English to the exclusion of other languages. Proposals to make English the nation’s official language have been floating through Congress since 1981 when the late Senator Samuel I. Hayakawa (R. CA), a Canadian-born semanticist and former college president, introduced the English Language Amendment. Though the joint resolution died, it set a pattern for congressional proposals, some less draconian, all of which have stalled. The most recent attempt was in 2023 when then Senator J.D. Vance (R. Ohio) introduced the English Language Unity Act.

Hayakawa went on to form “U.S. English” in 1983. It calls itself the “largest non-partisan action group dedicated to preserving the unifying role of the English language in the United States.” It currently counts two million members nationwide. In 1986, its then executive director Gerda Bikales tellingly warned, “If anyone has to feel strange, it’s got to be the immigrant, until he learns English.”

The group’s website now celebrates the Trump order as “a tremendous step in the right direction,” a supposed antidote to the 350 languages spoken in the United States. Obviously that level of diversity can also be viewed as a positive unless “diversity” is totally ruled out of even the lexicon. Two other advocacy groups with similar missions subsequently joined the movement: English First and Pro English.

Defying Democratic Norms

The fruits of those efforts can be found in official English measures in 32 states. The earliest, from Nebraska, dates from 1920 in the wake of World War I when suspicion of foreigners and their languages reached unprecedented heights. By 1923, 23 states had passed laws mandating English as the sole language of instruction in public schools, some in private schools as well. With immigration quotas of the 1920s (lifted in the mid-1960s) diluting the “immigrant threat,” the official English movement didn’t seriously pick up again until the 1980s as the Spanish-speaking population grew more visible. The remaining Official English laws were largely adopted through the 2000s, the last in 2016 in West Virginia. Some of them, as in California and Arizona, were tied to popular backlash against public school bilingual programs serving Spanish-speaking children.

Some of these state laws were passed by a voter approved ballot measure, others by the state legislature. Some reside in the state constitution, others in state statutory law. Unlike the Trump order mandated by executive fiat, they all underwent wide discussion by the people or their elected representatives, which a measure of such high importance, especially with national reach, demands. And they can only be removed using a similar process, unlike an executive order subject to change by the mere stroke of a future presidential pen. This is not like naming the official state flower or bird, a mere gesture. The consequences are far more serious.

As official English supporters are quick to point out, upwards of 180 countries also have official languages, some more than one. Standing alone, that argument sounds convincing. In well-functioning democracies, however, those pronouncements are carved into the nation’s constitution from the beginning or by subsequent amendment, or they’ve been adopted by the national legislature, again through democratic deliberation. At times they’ve been triggered by a particular event. France added the French language to its constitution in 1992 for fear that English would threaten French national identity with the signing of the Maastricht Treaty creating the European Union. Exactly what is triggering the current move in the United States? The answer is quite transparent. It’s immigration.

As official English supporters are quick to point out, upwards of 180 countries also have official languages, some more than one. Standing alone, that argument sounds convincing. In well-functioning democracies, however, those pronouncements are carved into the nation’s constitution from the beginning or by subsequent amendment, or they’ve been adopted by the national legislature, again through democratic deliberation. At times they’ve been triggered by a particular event. France added the French language to its constitution in 1992 for fear that English would threaten French national identity with the signing of the Maastricht Treaty creating the European Union. Exactly what is triggering the current move in the United States? The answer is quite transparent. It’s immigration.

Some countries, like Brazil and the Philippines, allow for regional languages. Other approaches are less formalized. In the Netherlands and Germany, the official language operates through the country’s administrative law. In Italy, though the Italian language is not officially recognized in the constitution, the courts have inferred constitutional status from protections expressly afforded linguistic minorities. Other countries, including the United Kingdom, Mexico, Australia and Argentina, the latter two also “settler countries,” recognize a de facto official language as the United States has done since its beginning.

Clinton Order Protections

While the official English declaration might mistakenly pass for mere symbolism, the revocation of the Clinton order quickly turns that notion on its head. Rather than “reinforce shared national values,” as the Trump order claims, revoking the Clinton order protections undermines a fundamental commitment to equal opportunity and dignity grounded in the Constitution and in Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. From that Act and its regulations prohibiting discrimination on the basis of national origin, the Clinton Administration drew its authority, including using national origin as a proxy for language, to protect language rights. In an insidious twist, the Trump executive order uses language as a proxy for national origin, i.e. immigrant status, to pull back on those same protections.

The Clinton order, together with guidance documents issued by the Department of Justice, required federal agencies and other programs that receive federal funds to take “reasonable steps” to provide “meaningful access” to “information and services” for individuals who are not proficient in English. As advocates argue, removing those requirements opens the door for federal agencies and recipients of federal funds, including state and local governments, to deny critical language supports that assure access to medical treatment, social welfare services, education, voting rights, disaster relief, legal representation and even citizenship. In a virtual world of rampant disinformation, it is all the more essential that governments provide non-English speakers with information in emergencies, whether it’s the availability of vaccines during a flu pandemic or the need to evacuate during a flood or wildfire, as well as the facts they ordinarily need to participate in civil life.

With current cutbacks in federal agency funding and staff, rising hostility toward immigrants, and the erosion of civil rights enforcement, one can reasonably foresee backsliding on any of those counts. One need only look at the current state of voting and reproductive rights to figure out where language supports may be heading when left to state discretion with no federal ropes to rein it in.

Multilingualism for All

The Trump order overlooks mounting evidence on the value of multilingualism for individuals and for the national economy. Language skills enhance employment opportunities and mobility for workers. Multilingual workers permit businesses to compete both locally and internationally for goods and services in an expanding global market

It takes us back to a time not so long ago when speaking a language other than English, except for the elite, was considered a deficit and not a personal asset and national resource. It belies both the multilingual richness of the United States and the fact that today’s immigrants are eager to learn English but with sufficient time, opportunity and support. They well understand its importance for upward mobility for themselves and for their children. That fact is self-evident. With English fast becoming the dominant lingua franca globally, parents worldwide are clamoring for schools to add English to their children’s language repertoire and even paying out-of-pocket for private lessons.

Rather than issuing a flawed pronouncement on “official English,” the federal government would better spend its resources on adopting a comprehensive language policy that includes funding English language programs for all newcomers, along with trained translators and interpreters for critical services and civic participation, while supporting schools in developing bilingual literacy in their children. Today’s “American dream” should not preclude dreaming in more than one language. In fact, it should affirmatively encourage it for all.

In the meantime, the Trump order promises to provoke yet more litigation challenging denials in services under Title VI and the Constitution, burdening the overtaxed resources of immigrant advocacy groups and of the courts. Worst of all, it threatens to inflict irreparable harm on thousands of individuals and families struggling to build a new life while maintaining an important piece of the old.

It’s not the English language or national identity that need to be saved. It’s the democratic process, sense of justice and clear-eyed understanding of public policy now threatened by government acts like the official English executive order.

Related content

In this episode of the Language on the Move Podcast, Rosemary Salomone chats with Ingrid Piller about her book The Rise of English.

]]>Migration separates families

I am a second generation migrant from my mother’s side. When my grandfather migrated from the former Czechoslovakia to Australia after World War 2, only one member of his immediate family was a fellow survivor, his older brother. The brothers were desperate to get out of war-torn Europe and start a new life, but there was a catch. They weren’t able to go to the same place. While my grandfather received permission to emigrate with his young family to Sydney, his brother received the same from the United States. Despite already losing their parents, grandparents, aunts, uncles and cousins in the war, the brothers were unable to prevent losing each other. After they emigrated, although they wrote letters, and spoke on the phone very rarely, they never saw each other again.

Today in Australia where I live and work, cross-border communication is likely to be by phone, not letter and for the majority of migrants the greatest barrier to seeing family is likely to be economic. Many of the participants I spoke to for my research into mixed language couples living in Sydney frequently spoke to family members by phone, sometimes even daily. This is significantly more affordable now than it was fifty years ago. However, migrant families continue to be separated for many years and often permanently. The border closures during the pandemic were a very difficult period for migrants unable to travel to spend time with family, particularly aging parents and relatives. So how does communication maintain family ties across borders? And how can we as scholars engage with this topic, theoretically, methodologically and ethically?

A theory of communicative care

I was recently lucky enough to speak to Dr Lynnette Arnold about her new book on this topic, Living together across borders: communicative care in transnational Salvadorean families. In the book she describes how communicative care both sustains and resists dominating geo-political forces which maintain continued migration from El Salvador to the United States across multiple generations as solution to meeting the economic needs of the nation.

In the book Arnold details an analytical approach based on the concept of communicative care. By this she means that the everyday communication which families engage in is an enactment of care, and that this care is “the most fundamental way that transnational families maintain collective intergenerational life in the face of continued, and seemingly endless, separation.” (p.6) She uses the term convivencia or living together, to describe the culturally specific practices she observed in her data collection with transnational Salvadoran families.

I found communicative care a particularly useful lens for examining the links between what are sometimes referred to as local or micro practices and processes and their connection to larger macro processes such as the economic and political systems governing nations. An example of this is the role of communication in maintaining the flow of global remittances which support the Salvadorean economy as well as the individual families. In this sense the book is a powerful tool for researchers who are interested in both a nuanced exploration of language practices in context and in the transformational power of research to speak back to hegemonic forces such as borders, global capitalism and neoliberalism.

Participants as researchers: researchers as participants

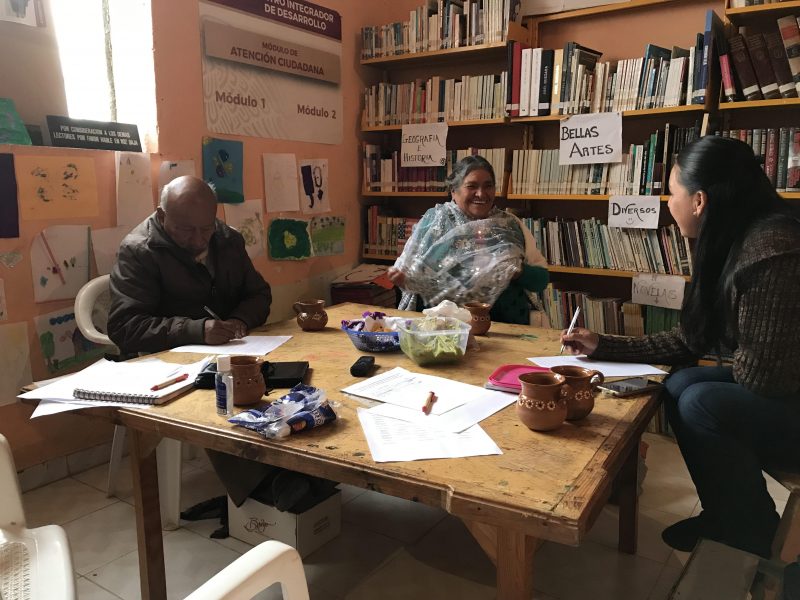

This study took a two stage approach to collecting the data. Starting with a lengthy ethnographic study of a village in El Salvador where she lived and worked as a young women, Arnold built up relationships with two transnational families. These families then formed the research participants for the second stage of the study, where four months worth of telephone conversations between migrant and non-migrant family members were recorded.

This stage centred the agency of the participants themselves by training them as data collectors of the recorded phone calls between transnational family members. In the interview, Dr Arnold discusses how she also employed research assistants from El Salvador who recognised the social identities – as well as the language varieties – of the research participants. This facilitated their contributions, both as accurate transcribers of the audio data but also as cultural informants in the data analysis process.

The ethics of working with migrants and language issues

For those of us working in the field of migration and language, how can we behave ethically in a space where there are profoundly unequal power relations, the stakes are high and global tensions continue to bubble around issues of migration, borders and citizenship? This is especially true for scholars like me, who are not first generation migrants themselves and thus speak from a relatively privileged position.

According to Arnold, we can start by asking what is language doing? How does it connect with the relational aspect of people’s lives and the geopolitical contexts they exist in? Thinking critically about the role of language in creating social reality allows us to become informed advocates for linguistic diversity. It enables us to think about issues of access, inclusion and ultimately social justice.

I’ll leave you with one example from the book’s conclusion which I found particularly compelling due to my own research interests into the links between language maintenance in migrant families and second language education. Arnold makes the point that one way we can support transnational families to maintain networks of communicative care is to change existing educational language policy “which all too often functions as a tool of state-sponsored family separation by pushing the children of migrants towards monolingualism in dominant languages like English” (p. 171). Instead of turning bilinguals into monolingual, language in education policy must be guided by what migrant families themselves need, which is the communicative resources to maintain ties across borders. This includes a recognition of the linguistic variety in migrant repertoires, which extend way beyond standard languages.

Reference

Arnold, L. (2024). Living Together Across Borders: Communicative Care in Transnational Salvadoran Families. Oxford University Press.

Related content

Piller, I. (2018). Globalization between crime and piety. Language on the Move. https://languageonthemove.com/globalization-crime-piety/

Weiss, F. (2012). Christmas in Nicaragua. Language on the Move. https://languageonthemove.com/christmas-in-nicaragua/

Transcript

Hanna Torsh: Welcome to the Language on the move podcast, a channel on the new books network, my name is Hannah Torsh, and I’m a lecturer in linguistics and applied linguistics at Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia. My guest today is Dr. Lynette Arnold, Dr. Lynette Arnold is an assistant Professor of Anthropology at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and we’re going to talk about her new monograph living together across borders, communicative care in Transnational Salvadorian Families published by Oxford University Press. Welcome to the show. Lynette.

Lynnette Arnold: Thank you so much. Hi, everybody! Ola.

Hanna Torsh: Can you start us off by telling us a bit about yourself, and how you got interested in the topic of your book?

Lynnette Arnold: Sure! So my book, Living together across borders, explores how members of transnational families find ways to live together despite being separated across borders. The families I work with are from a small rural village in El Salvador, with migrant relatives living in urban locations across the United States. I am not Salvadoran. I do not have Salvadoran family members. So you might wonder, what is it? How did I get involved in this? And my interest in this topic really emerged from 2 different but interrelated personal experiences.

I spent 5 years living in El Salvador from 2,000 to 2,005 during the years when most people are in college. I was living in El Salvador, and this is a really eye opening experience, because I got to know many young people, my age, who had grown up during the Salvadoran Civil War that happened in the 19 eighties, and in getting to know them I learned a lot about the involvement of the Us. Government in perpetuating this 12 year conflict through immense financial support of the Salvadoran military and training Salvadoran soldiers in brutal, scorched Earth tactics. All of these, the ways that us support had really caused a lot of harm in El Salvador, and that was an eye opening experience for me to realize that this big gaping hole in my education as a Us. Citizen not understanding something so vital about my country’s history and involvement in the world.

So that was one inspiration was really to help my fellow citizens better understand the human impact of us foreign policy. Our involvement in the Salvadoran Civil War was a direct cause of the widespread emigration that El Salvador shows still today. And so that was kind of one piece was recognizing that I hadn’t learned these things and wanting to share them with my fellow citizens.

The second experience was sort of more deeply relational, and it has to do with the ways that the relationships I made in El Salvador continued. When I moved back to the United States to go to college. When I moved to the US. I stayed in contact with people in El Salvador through phone calls, and I suddenly found myself part of this transnational network of folks in El Salvador, their relatives here in the United States, who I had met in El Salvador, but who had since migrated, and I started to get really interested in what was happening in those phone calls and all the kinds of complicated things that people were working out on the phone across borders. At the same time, at that moment in my life I was navigating a kind of growing realization or separation from my own family of origin. I had left at that point permanently left the Christian Commune where I was raised, and where my family still lives, so I have a very different reason for separation. But I was navigating in my own life how to be family with people that I wasn’t living together with. And so, though I juxtaposing those 2 experiences, got me really interested in how people do family at a distance and the role of language? So that was really what brought me then to the topic of the book.

Hanna: That’s so fascinating. And just a quick follow up question. You know you talk about living there, living in this rural village at a time when sort of other people were at college. How was that experience of language learning for you at that age, in this very remote community, especially when we consider today how almost how difficult that experience is to have with the new affordances that we have in terms of technology and the reach of technology.

Lynnette Arnold: That’s such a great question. Yeah. So I went to El Salvador, knowing very little Spanish. I had been raised in a kind of bilingual culture with German. So I had German as kind of a heritage language, not for my family, but from my community growing up and understood a lot of German, but went to El Salvador, so I knew how to be bilingual. I didn’t know Spanish. I took 2 weeks of intensive one-on-one Spanish courses in the capital.

And I told the guy, the instructor like this is what’s going to happen. I’m going out to this rural village by myself for the next 4 months like I need to be able to survive in Spanish, and I had a dictionary, and I had a grammar workbook and then I went out into the village. I knew one other person in the country who spoke English, who I saw maybe twice the entire time that I was there. So it was really immersion. I was living with a family. I was trying to figure out how to, you know, support the English teacher who didn’t really speak English, you know, like all of these things while also learning the language. So I think obviously, having already been bilingual, helped me like my brain, knew how to learn language, knew that, like learning, the grammar was helpful, and that then I could be like, oh, that person just used the subjunctive! That’s what it sounds like in real life, you know. I remember having experiences like that.

I think the other thing that came out of that experience for me was that I was really learning the language and the culture at the same time. So it wasn’t that I was learning these abstract grammatical forms, but I was learning how to communicate in the language as a young woman, so that was the other, like the gendered, and age the fact that I was, you know, a Us. Citizen, a foreigner. All of those things I had to learn how to use Spanish in that very kind of accurate, contextual way. And still to this day, when I speak Spanish, I find myself realizing how much that has influenced the way that I speak Spanish today. People are not familiar with my accent. I have a very Salvadoran accent. The vocabulary that I’m most comfortable with is like about farms, and, you know, growing food and animals and raising children and not, you know, academic things. And I think that experience was certainly also influential in shaping my research trajectory and the project of this book, because it made me think a lot about the really close connection between language and culture and the sort of social work that language does.

Hanna Torsh: Yeah, wonderful. I think a lot of our audience can resonate with that experience of finding their voice in another language, and having to learn how to be an identity in that language, and then perhaps shifting to another space, and having to then relearn how to be in that language.

So moving on to your book in your book, you talk about two really important concepts, and I’m interested in hearing what these mean. I think our audience would like to hear about them, too. So the 1st one is this idea of convivencia, or living together, and the other one is the idea of communicative care. Can you explain what these 2 concepts mean, and how you use them in your research and in the book.

Lynnette Arnold: Sure I’ll start with convivencia, because it’s the title of the book. So convivencia is two words; con together, and vivencia, live, so live together, made into one word in Spanish convivence as a noun form. It can be all these different things. It’s really a flexible word. People use it a lot when talking about social life. In El Salvador in general, it’s just a very high frequency word. Convivio is another related noun, that is a word for a gathering. Many different kinds of gatherings can be called convivios.

So, in addition to using the word convivencia a lot. People also spend a lot of time carving out opportunities for convivencia or living together what we might call at least an American lingo hanging out just spending time. So it’s a very common thing in rural Salvador culture to see people sitting around on the patio, kind of intermittently talking. Maybe somebody is doing some husking of corn or some other kind of work is happening. Children are in or out, in or out but that sort of spending time together, talking, hanging out, not doing a whole lot of anything is a really important part of the culture. Sometimes convivencia happens in more formal ways, like big gatherings for birthdays, or, you know, religious celebrations or things like that. But they can also be much more informal.

So when I this really sort of caught my attention in the context of the book project, because when I talk to members of transnational families both in El Salvador and in the United States. Many of them mentioned that they missed the ways that they used to convier with loved ones. So they missed that kind of living together when they were separated across borders. So I heard that truth coming out over and over in the interviews, but at the same time from my research perspective, I was seeing these families still doing a whole heck of a lot of conviviando. Even if they weren’t in the same place, they were still finding ways to live together. So I knew that from participating in the transnational networks that from sort of a research perspective, convivencia was still happening, but families were telling me that it looked different than it did when they lived together.

And so, as part of the kind of participating in these transnational phone conversations. I really started to realize that my intuition about where a lot of this living together was happening was that it was happening in these phone calls and these transnational conversations were a really crucial way that families were still able to live together when they couldn’t be in the same place. So that’s what really got me into thinking about what’s happening with this communication and communication away as a way of being together, living together when you’re separate.

So that seems like, if we want to put a label on it, we could call that the more Emic framing right the more the way that people in the community would understand what’s happening here. Convivencia is probably the label they would put on it. Communicative care is really my term and is kind of more informed by my theoretical considerations. I’m a scholar of language and communication, and I’m very interested in how language acts in the world and what language does. And at that time I had been thinking a lot about and reading a lot about feminist scholarship around care and feminist scholars, writing about care often describe it and define care as the labor or the work that we do to keep ourselves alive as a species. So it’s the work that allows individual and collective well-being and survival.

And I came to feel that what was happening in the conversations was families doing precisely that work through language? So I decided to come up with this idea of communicative care as a theoretical frame to capture what I what I thought the work was that was happening in the Conversations. I also wanted to label for the fact that I saw that care and communication were entangled in some very complex ways, and so I wanted a framework that could capture all of those different ways of entanglement. So I decided the communicative care would be a capacious way to talk about that.

Hanna: So just for our audience to understand, you have talked about those transnational phone calls. So maybe we could just take a step back and you could just describe the actual data that you work with in this book, so that so that we have a context for that.

Lynnette Arnold: The data that I’m working within the book primarily are recordings of transnational phone calls. So they are dyadic, mostly dyadic conversations between a person in the United States and a person in the El Salvador who are related to one another in some way. I have interviews and other kinds of ethnographic data that I use to sort of triangulate. These were conversations that were recorded over a 4 month period. So in many cases I could track how something developed over time. The conversations involved, although they were dyadic, many different dyads within the family. So I could track how different dyads talked about different issues.

So that’s when I’m saying that the families are doing a lot of this conivencia, this living together through conversations, I was able to see that in recording, these phone calls and paying really close attention to what exactly they were doing when they were talking to each other on the phone and why they spent all of this, you know, effort, money and time to have these regular phone calls with one another.

So I felt the need for a framework, because I wanted something to capture the different ways that language and care were connected. So it was very clear to me that language is something that makes other kinds of care possible. So think about many kinds of care that we all engage in on, you know, part of our everyday lives. Language is absolutely central to those for these families. The money that immigrants send home is probably the form of care that most people associate with transnational families. That is not possible without communication. There’s a lot of communicative work that goes into making those remittances, those economic transfers happen. But beyond that I wanted to show. And I show in the in the book that language enacts care. Language is something that does itself do care work. It’s a way of maintaining and forging the kind of relational bedrock that is the foundation of all other kinds of care. So that was really important to me to draw that out. That language is not just facilitating other care, but that it is itself a kind of care. And then also, as we know, scholars of language know, language is always making meaning. So as it’s facilitating remittances. And as it’s enacting relational care, language is also a way that people. I used to create meetings about like what kinds of actions, when carried out, by which people count as care and which things don’t count? So all those things are sort of entangled and happening at the same time. So with a communicative care perspective, I was really trying to come up with a theoretical and analytical way to approach that and fully grapple with what was happening with this communication. And the book demonstrates ultimately that communicative care.

This approach really sheds light on how transnational families are able to forge convivencia and live together across borders, through language when they can’t be at the same place for many years at a time.

Hanna Torsh: One of the things that I found really fantastic about reading your work is that the approach you took to data collection, this very inclusive, very participant centered approach to data collection. Could you tell us a bit about how you approached the methodology in your work, and why?

Lynnette Arnold: Sure. And I want to answer this question in a way that will be helpful to emerging scholars who are maybe formulating their first research project or anybody embarking on a new research project. Because, as we know, things often don’t go to plan when we’re doing research. In fact, they often tend not to go to plan but really, if my research had gone to plan, I would not have the book that I have.

So that’s the kind of message here that things can go differently than you imagine, and still be great. So my project started off as a very traditional ethnographic. Sort of like an ethnography of communication. In that tradition I did a lot of participant observation in El Salvador and in the United States with family members, spending time in their homes, eating meals with them, hanging out on the weekends, trying to go to their workplaces, going to their schools. Just kind of spending time understanding what was happening in their lives. And then I conducted interviews with members of families in both countries. And I had that, you know, interview data that I recorded and started to analyze, and, you know, have some other work about narratives that were told in those interviews, for instance.

And then I was planning to do a longer stint in El Salvador of sort of more intensive ethnographic research, and really tracking what was happening. Over an intensive period of time in El Salvador. But then things beyond my control happened. Things got very dangerous in El Salvador. So this was in 2,014 which was a time when there was an intense spike in organized crime and gang violence, especially targeting young people. And there was a whole crisis of unaccompanied minors coming across the Us. Mexico border in relation to this and the area where I do. My research is kind of on a line between the territory of two gangs and got incredibly dangerous.

So my advisor felt like it was really unsafe for me to go back and spend a long time in El Salvador, and she was probably right. So I had to pivot and I decided to pivot to a project that was much more focused on the transnational communication.

So I ended up focusing on the phone calls and deciding to work with two extended families that I had. I knew the most members of and had the deepest relationships to. And I worked with them to record phone calls that they made across borders over a period of 4 months. I based on the interviews I had a sense of from the interviews how much people spent on phone calls per month, and I gave families this kind of stipend per month to cover the costs of the communication during the time that the recording was happening, and then I also hired research assistants in in each family. These were in both cases young people living in the United States because I was able to get to them and train them. So these were young people who were more tech savvy, who were literate and who crucially didn’t have tons of family obligations like they weren’t parents yet and so I was able to go visit them and train them in how to use the recording technology. I used a very, very simple earpiece recorder that you just held the phone up to. I had a little carrying thing for the recorder, so people could still walk around on their cell phones. These were all cell phone calls while having a little MP. 3 recorder on the kind of in their holster

And the family decided amongst themselves which calls to record. And then they didn’t necessarily have to pass all the recordings on to me. They could delete data if they wanted to. I still did delete some things that were passed on to me that I felt, especially when they were pertaining to people’s immigration situation. That I felt like legally, I didn’t want to be responsible for having that information. So I just deleted those recordings.

So that was the sample that I got was the things that families, you know felt okay about me having. And I was still surprised. You know they still felt very from my experience, participating in these networks, very authentic conversations. And there’s conflict. And there’s, you know, disagreements. There are things that happen in these calls. So I I would definitely say it’s not a entirely representative sample in that. Maybe, like the most extreme cases of conflict were not recorded, or whatever but I didn’t get the sense, either, that people were like consistently, always on their best behavior on these phone calls, for instance, it felt like they had. You know they were kind of in the habit of doing this.

Hanna: What did you then do with the with the recordings that you had. How did you go about analyzing that data?

Lynnette Arnold: Yeah. So this is another thing that many of us who do language research, you know, end up with hours and hours of recorded data, and we want to look at it closely, and it gets really overwhelming. So one thing I did that I learned from my undergraduate advisor, Mary Bucholz, was, instead of transcribing all my data. First, st I did a 1st pass of doing what’s called an in what she calls an index, which I think, is a good term. So you’re making a time stamped kind of account of what is happening every minute or so. 30 seconds, depending on how fast moving. The data is in the call, and that is a good way to listen through your data. And just what is in there, what’s happening. Get it in your head right in a way that maybe transcribing especially. This was obviously in the time before AI. But I know now lots of people are using AI to do a 1st pass on transcription. It’s not getting the data in your head in the same way. So working through an index is really good because it makes you start to see the patterns so indexing allowed me to do some qualitative sort of coding of what were some communicative patterns that I started to see what were. Think, what were things that people were doing over and over and over and over again? And decided to focus on transcribing, then, examples of those things that were happening a lot, and you’ll see if you read the book that there’s a chapter about greetings. That’s a thing that happens a lot in these phone calls. And by an example of greetings. There is a chapter about negotiating remittances which is also a thing that’s probably the thing that happens for most of the time.

And then there’s a chapter about remembering in conversations kind of reminiscing in conversations, which was one that I hadn’t, you know. It wasn’t 1 that I went in looking for necessarily but jumped out at me as something really powerful that was happening in these conversations. I was really fortunate.

During my graduate time, when I was collecting and preparing the data to be able to work with undergraduate research assistants. All of whom were Salvador of Salvadoran descent, which meant that they had the linguistic capability to understand this variety of Spanish I think at one time I tried to work with a Mexican descent student, and they were just like this. Spanish is so different from the Spanish that I’m familiar with. I don’t think I can transcribe this accurately. So it was a lovely, lovely opportunity to also extend mentoring towards you know, 1st generation largely Salvadoran American students who were an amazing help for me as well in doing the transcription, and they are all named in my acknowledgements.

Hanna Torsh: Excellent. Yeah, that’s that’s a real challenge for us here in Australia, because we are so linguistically diverse. Having that match with research support in terms of linguistic repertoire.

Lynnette Arnold: And I think even in doing the transcriptions we would meet to talk about the transcriptions. But our conversations would diverge just from the actual transcript. And they would say things like, Oh, my mom. Salvi, mom, this is a thing my mom does all the time. Or, you know, topics of conversations. They were all parts of, you know, transnational families as well. So it was really enriching, not just in the transcriptions, but also in helping me to recognize that what I had in my data was something that was broader than just the two families I was working with.

Hanna Torsh: In your book, you talk about the contradictory ways that digital communication has impacted on the families that you worked with, but also on transnational and cross border family communication generally. So could you tell us a bit about what you found out about these contradictions for your research participants, and any examples that you had would be also fascinating to hear.

Lynnette Arnold: I think there’s kind of a couple of possible answers here. And I think I’ll go with. There’s like a technology answer. And then there’s like a social life answer. And I think we maybe can do both. The technology answers that we often assume that like newer technology, more inclusive, like video technology is better and that people will default to using technologies that are more complete. So if families have access to video calling, they will use video calling, for instance, research with transnational families beyond mine. But just within the field of transnational family research has found that video calling can actually be very emotionally challenging and costly for people to engage in, and that sometimes people dis prefer, even if they have access to videos, that they prefer other forms of communication. So I argue in my work that for these families, phone calls are a real sweet spot. Because they don’t require as mo as much emotional investment. I mean, imagine yourself as a parent or as a family member separated from your loved one for years at a time. You see them on screen, and you see in real time that they’re different than they were when you were there with them. So it’s a real physical visceral reminder of the passing of time that you’re not together. On the phone that is a little bit more held at bay. But you still have the intimacy of somebody’s voice, and you can really hear all of those cues of emotion and all of those things that are so important, especially in the sort of delicate communication that families are doing often on the phone.

Phone calls are also very accessible. So I think that’s another thing to think about in terms of technology is like, and the family is who within the family can use a given technology and phone calls for the families I worked with were maximally inclusive because preliterate children can still talk on the phone and also in the families I worked with elders, and the families were often not literate or had very low literacy levels, and certainly did not have technological literacy to know how to navigate something more complex than a phone call. So phone calls were really a sweet spot, both kind of relationally and what they allowed but also because of their accessibility to everybody within the family. So talk a little bit about that in the book. Why, phone calls in this era of all polymedia. I felt the need to talk about that. It also had to do with the fact that smartphone technology hadn’t really entered El Salvador quite yet. Now it has but I still talk on the phone to my comrade. The mother of my goddaughter in the El Salvador we sell each other voice memos on Whatsapp. So you know again, you see that kind of preference for the voice communication over over video, even though it’s now more possible than it used to be.

And then there’s another answer that has to do with what digital communication affords for these families in terms of their relationships. So as I’ve been talking already, on the one hand, communication is absolutely vital. It’s the way that families are able to live together and sustain their relationships across border. It’s a means of emotional support. It forges the groundwork for this ongoing economic support like remittances. So it’s really positive things for families. But we also know from transnational family scholarship in general that digital communication for families can be really charged. It can lead to people feeling surveilled or micromanaged, especially children and women in families.

In my book, I found that kind of the the negative consequences or effects of digital communication were the ways that it perpetuated divides between migrants and non migrants within families. So if you think about a transnational family, you’ve got this big division of people living in different countries, and the migrants are perceived as those with access to more resources, and the non migrants as those with less access to resources who need help from their migrant. This is kind of a pretty broad generalization that holds for most transnational families, I think.

And what I found in my research was that this divide played out in communication, so that in family conversations there were very different communicative expectations placed on people depending on if they were migrants or non migrants. So, for instance, non migrants needed to learn that when they needed remittances they shouldn’t just ask. They shouldn’t just say, Hey, can you send me 100 bucks?

But they should tell these elaborate stories about family life in El Salvador, in which they would embed conversations of somebody else complaining to somebody else about needing money. So this very like indirect, layered way that people learned a very specific way of doing like a remittance request right?

And then, if you zoom out to think at the kind of macro level. This kind of communication is sustaining and shoring up migration right? It sustains the transnational family form. It keeps the remittances flowing so from a nation perspective, it makes migration succeed as an escape valve, as a means of generating revenue through migrant migrant remittances. Right? So in that those ways, we can see that the communication is really shoring up some inequalities right at the interpersonal and kind of the global level.

Even as it’s a lifeline for these families. So both of those things are true at the same time. And I just want to kind of end by saying it isn’t the case that communication only re in reinscribes inequalities. There are. There are ways in which communication also opens up space for people to resist and create, create new ways of doing things.

Hanna Torsh: Yeah, I’m I’m really keen to hear if you could tell us about some of the participants that you talk about in the book, and some examples of those ways of maybe either kind of perpetuating those inequalities or resisting those inequalities.

Lynnette Arnold: Yeah, I think I’ll go with the resisting examples, because they’re more interesting to me.

Hanna Torsh: Sure.

Lynnette Arnold: So one thing that’s really interesting about digital communication is that it opens up ways for young people to participate in family communication. So some transnational family research shows that young people are actually really get involved in family communication because they have to be the tech. And they’re let the tech help, you know, and then they’re there helping grandma with the laptop or whatever, and then they participate in the conversation. In my families, I found that the kind of a polymedia kind of situation where there were phone calls, but also other kinds of technology happening. Between family members opened up some conflict. So in this one case, some young men were being raised by their grandparents in El Salvador, and their dad was in the United States. He sent them a laptop. They opened Facebook accounts. They started messaging their dad on Facebook. Their grandparents are not literate. Their grandparents are not tech literate. They have no idea like what’s happening when their sons are on the laptop and so the sons use this kind of private channel of communication to complain to their dad about some stuff like teenagers do right.

Hanna Torsh: Yes, I do. Yes.

Lynnette Arnold: As they do and the dad was just hearing from them about this, and so then he called his parents, and, you know, kind of scolded them, taking his son’s word as like you know the truth rather than realizing that it was just kind of one perspective on what was happening. And this resulted in a lot of conflict within the family that then got resolved by multiple phone calls from multiple people, in which people then navigated and kind of smooth things over, and he eventually called and apologized to his mother for not understanding the situation more clearly. But so there there was a case where young people were using technology to kind of have more agency right in what’s going on in the family and try to pressure, you know, put some weight on the scales in terms of things coming out in the way that they wanted it to come out. The other example that I I like to talk about and think about is about gender. So we haven’t talked about gender yet, but it is a theme throughout the book. We know from feminist work that women around the world do the lion’s share of care in pretty much every context you can think of, and that is also true in communication.

I do have cases of men doing amazing communicative care work, a lot of like really touching emotional communication between men. So this is not to say that men are not doing the work. But one thing that I find is that women get asked to do kind of the most onerous tasks. So if a report about oh, the migrants sent money for the cornfield, and there was a flood, and all the corn seedlings died, and we need more money so that we can replant women get asked to have that conversation, even though agriculture isn’t traditionally feminine domain. But they get asked to kind of communicate that information and take on that less pleasant communicative burden. But what I found in some cases was that sometimes women were then using that that they were put in this kind of conduit position to migrants. They were using that to kind of carve out more space for themselves within family decision making. So in one instance, the father in El Salvador had sold one of the family’s cows. He had not consulted with his daughter, his eldest daughter, who lived with him in El Salvador about this decision, and she was kind of mad that he hadn’t consulted with him. But then he this was the same corn example. He needed her to talk to her brother in the United States, his son, and, you know, get some money for the corn so he came over at one night and asked her to do that the next time her brother called to ask him for more money so that they could replant I happened to be there when the brother called, and she didn’t say anything, but instead she told all about the cow, and how her brother had, how her dad had sold the cow without consulting with her, and how it was a poor decision and a waste of the family’s resources and blah blah, and that she should be consulted. So really getting a kind of word into the migrants. And then, when her Dad came back the next day to see what had happened. And what if the money was coming? She was like? Well, I didn’t tell him about it, because, you know, if I’m not consulted on things, I I can’t. You know I can’t communicate. So she really kind of used her. She was in this pivot Lynch kind of PIN position communicatively, and she used that to try to press for a like more decision, making power within the family in these kind of agricultural domains that traditionally, in traditional kind of salvadorange roles would not have been within her purview. So those are the kinds of things, and I think there were more of those things happening than I saw where people were using women especially. We’re using communication to do this kind of torquing in the mechanical sense of gender roles and kind of incrementally shifting things a little bit. So all that’s to say, I think that there are.

There were other ways to in which people were using communication to resist. So I in my, in my account, I wanted to kind of resist. One size fits all characterization of what was happening here, and really capture the complexity of communication as a wonderful lifeline for these families, but also as reproducing inequalities, and also maybe sometimes allowing for resistance, especially to gender them, and generational hierarchies within families.

Hanna Torsh: That’s wonderful. It’s a great example it kind of reminds me of also the the kind of dual role of women in households where they have to do the bulk of the domestic labor, but that also affords them a certain amount of power over some decisions. And so it’s often hard to for them to give it up, because that is then their only power traditionally, in the in those sorts of family situations. So I think that’s a yeah. And it’s really interesting, the way that intersects them with the digital world. And how the same sort of negotiations are taking place. So like, Okay, well, if this is my job, then I am going to try and carve out more agency for myself in a system where I have less agency, you know a patriarchal system. So yeah. Oh, look I I would love to talk more with you, but I am have to jump to my last question. And and and make it really open for you. I I think one of the one of the things that you talk about in your book is how you’re essentially interested in, in, as you say, providing a much more contradictory and nuanced picture of particularly transnational migrants when they have been traditionally particularly, you know, in in public discourse, cast as victims and and and really there’s been a lot of focus on the negative. So I guess I would like to ask you, you know, what? What did you? What are the key? Things that you would really like? The key findings. You would like emerging and established researchers in linguistic diversity and in transnational migrants, to take away from your wonderful book.

Lynnette Arnold: Thank you. I’ll start with a linguistic diversity piece. And I just the I cannot say strongly enough that we cannot. We can’t study linguistic diversity without also be thinking, thinking about what language is doing. So linguistic diversity cannot be separated from the function of language. What people are doing with their communication and the context in which they’re doing those things really shape what linguistic diversity does and what it’s made of. So it’s really vital to think about. One of the main things that people are doing with their communication always is relational. They’re doing relational work of all kinds, with family members, with bosses, with everybody. Right? We’re constantly managing relationships through our language. And so we need to think about that. And also the kind of geopolitical context within which those relationships are playing out. So this may get to your question about language maintenance. Actually, because I wanted to talk here for a little bit about the children of migrants in the United States. So I noticed in my research that the children of migrants in the Us. Were largely excluded from transnational communication.

This was not the case for children in El Salvador, who participated quite actively in and were trained actively trained to participate in the transnational communication, as I show in my chapter on Greetings. That shows how kids learn even before they’re verbal. They’re taught how to do these greetings.

So why does that happen? Well? Linguistic diversity is part of an answer to the question. Relatives in El Salvador tended to perceive the children of migrants in the US as not being Spanish speakers, and therefore they perceived the language barrier that kept them from communicating with grandchildren, nieces, nephews.

Whatever the relationship was, there are, of course, language barrier issues here. There are educational issues at play. Many of the children in the United States did not have access to bilingual education in Spanish and English, and obviously the social dominance of English, certainly reduced Spanish fluency for some, at least, some of the children, but many of the children who were perceived in El Salvador as monolingual English speakers would actually be characterized as bilingual. They just didn’t speak Salvadoran Spanish. They spoke US Spanish, which is a variety of Spanish that has large has been in contact with English right for a long period of time. And so it’s grammar. Its vocabulary is shaped by English and so I think that the unfamiliarity of the children Spanish was perceived by some relatives in El Salvador and this dialect difference was perceived as a as a full on language, barrier, and led to to children being excluded.

So the linguistic causes of children’s kind of exclusion from family communication were really complicated. But it’s also important to recognize that their exclusion from this communication was also influenced by non linguistic, relational and structural issues. So when families envision their future generations down. You know they envision the future of continued emigration, of continuing. So today’s children in El Salvador are tomorrow’s future immigrants. And so it was really essential for children in El Salvador to be heavily socialized into being members of transnational and families to being committed to these cross border relationships, because they would then be the ones to carry those seeds with them. When they traveled the children of migrants are seen as kind of less predictable sustainers of transnational families like well, they just really weren’t sure what was going to happen with these kids.

They weren’t sure they were going to stay committed to the family, so they were less pro. Those relationships were less prioritized in the kind of communicative care work that families were sustaining across borders. The relationship with children in the in the Us. Just wasn’t a priority. Because of this way of thinking about right and this way of understanding their future makes a lot of sense from a geopolitical perspective. It’s heartbreaking.

But I think, unfortunately, realistic reading of the inequitable global distribution of resources, and that for families to get access to those resources. People are gonna have to keep migrating right? So what this example shows us is that the kind of linguistic, the relational, the geopolitical, are all like really tightly entwined with each other. So I just want this example to sort of be a call for us as researchers of linguistic diversity, to be able to think on all of these scales at once, and to think about their interconnections.

And for me, thinking about what language is doing in the world for people. What people are doing with their language is a way to get at that and the lens of care has been a really for me a very capacious lens that has allowed me to think about the relational and interpersonal and the geopolitical kind of within the same framework and their interrelationships. So that’s really my big takeaway for kind of language researchers. Is to think about what language is doing?