In this episode of the Language on the Move Podcast, Brynn Quick speaks with Dr. Hannah White, a Postdoc researcher at Macquarie University in the Department of Linguistics. She completed her doctoral research in 2023 with a thesis entitled “Creaky Voice in Australian English”.

Brynn speaks to Dr. White about this research along with a 2023 paper that she co-authored entitled “Convergence of Creaky Voice Use in Australian English.” This paper and the entirety of Hannah’s thesis examines the use of creaky voice, or vocal fry, in speech.

This episode also contains excerpts from a Wired YouTube video by dialect coaches Erik Singer and Eliza Simpson called Accent Expert Breaks Down Language Pet Peeves.

If you liked this episode, also check out Lingthusiasm’s episode about creaky voice called “Various vocal fold vibes”, Dr. Cate Madill’s piece in The Conversation entitled Keep an eye on vocal fry – it’s all about power, and the Multicultural Australian English project that Dr. White references (Multicultural Australian English: The New Voice of Sydney).

If you enjoy the show, support us by subscribing to the Language on the Move Podcast on your podcast app of choice, leaving a 5-star review, and recommending the Language on the Move Podcast and our partner the New Books Network to your students, colleagues, and friends.

Transcript (added 19/12/2024)

Transcript (added 19/12/2024)

Brynn:

Welcome to the Language on the Move Podcast, a channel on the New Books Network. My name is Brynn Quick, and I’m a PhD candidate in linguistics at Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia. My guest today is Dr. Hannah White.

Hannah is a postdoc researcher at Macquarie University in the Department of Linguistics. She completed her doctoral research last year in 2023 with a thesis entitled Creaky Voice in Australian English. Today we’re going to be discussing this research along with a 2023 paper that she co-authored entitled Convergence of Creaky Voice Use in Australian English.

This paper is also Chapter 5 of her thesis. The paper and the entirety of Hannah’s thesis examines the use of creaky voice or vocal fry in speech. Hannah, welcome to the show and thank you so much for joining us today.

I’m so excited to talk to you.

Dr White: Thank you so much for having me. I’m also excited.

Brynn: To get us started, can you tell us a bit about yourself and what made you decide to pursue a PhD in Linguistics?

Dr White: You might be able to tell from my accent that I am a Kiwi, a Kiwi linguist working here in Australia. I actually kind of fell into linguistics by accident. So I was doing my undergrad in French and German, and I went to Germany on exchange, and I took just on a whim, I took an undergraduate beginner English Linguistics course, and I realized this is what I want to do forever.

I fell in love immediately and came back and added a whole other major to my degree. So yeah, it was kind of by chance that I found linguistics. And in terms of doing a PhD, I just, I love research.

I love the idea of coming up with a hypothesis, designing an experiment to test it and finding like results that might kind of challenge. Ideas that you’ve like preconceptions that you have or yeah, just finding something new. So yeah, that’s kind of what drew me into doing the PhD and in linguistics.

Brynn: Did you go straight from undergrad into a PhD?

Dr White: No, I didn’t. I had a master’s step in between. So, I did that in Wellington.

Brynn: I was going to say, that is quite a leap if you did that!

Dr White: Absolutely not. I did my master’s looking at creaky voice as well. So, I looked at perceptions of creak and uptalk in New Zealand English.

Brynn: Well, let’s go ahead and start talking about that because I’m so excited to talk about creak and vocal fry and uptalk. So, your doctoral research investigated this thing called creaky voice. So, whether we realize it or not, we’ve all heard creaky voice, or as I said, is it sometimes called vocal fry.

So, tell us, what exactly is creaky voice? Why do people study it? And why did you decide to study it?

Dr White: Okay, so creaky voice is a very common kind of voice quality. Technically, if we want to get a little bit phonetics, it’s generally produced with quite a constricted glottis and vocal folds that are slack and compressed. They vibrate slowly and irregularly.

And this results in a very low-pitched, rough or pulse-like sound. You can think of it, often it’s described as kind of sounding like popcorn, like popping corn or a stick being dragged along a railing. They’re quite common analogies for the sound of creaky voice.

Why do people study it? I think that it’s something that people think that they know a lot about. And it’s talked about a lot.

But it’s actually kind of, there has been research on creak for a very long time, since the 60s. It’s gaining popularity at the moment. So, I think it’s a relatively new area of research that’s gaining a lot of popularity right now.

This could be to do with the fact that there’s a lot of media coverage around creaky voice or vocal fry.

Brynn: Because we should say that the probably most common example that we’ve all heard is Kim Kardashian, Paris Hilton, saying things like, that’s hot, like that, that like, uh, sound voice, yeah.

Dr White: The Valley Girl.

Brynn: Valley Girl, yes.

Dr White: My go-to examples, Britney Spears as well.

Brynn: Oh, absolutely.

Dr White: Yeah. So, a lot of this media coverage, it’s associated with women, right? But it’s also super negative.

So often it’s associated even in linguistic studies, perception studies, it’s associated with vapidness, uneducated, like stuck up, vain sort of persona. So, I think it’s really interesting to kind of, that’s what drew me into study, wanting to study it. I do it all the time.

I’m a real chronic creaker and I love the sound of it personally. So, I kind of just wanted to work out why people hate it so much and see if I can challenge that view of creak.

Brynn: Yeah, and it is true that we tend to associate it with, as you said, with vapidness. Do we have any idea of where that perception came from? Or was it just because it’s more these people that are in the limelight, younger women, the Kim Kardashians of the world, is it because we associate them with being vapid and that’s their type of speech, or do we know where that came from?

Dr White: I don’t know if there’s any research that’s kind of looked at where that association came from originally, but I would say, like just from my own perception, it probably is that association with these celebrities.

Brynn: And these celebrities that we are talking about are generally American, right? But in your thesis, you discuss creaky voice use in multicultural Sydney, Australia. And you write about how social meanings are expressed through the use of creaky voice.

So, can you tell us about that? Where you’re seeing creak come up in Australia? Maybe why you’re seeing it come up and what you saw during your research?

Dr White: I mean, creaky voice is used by everyone. It’s a really common feature. It’s used across the world in different languages.

It can even be used to change the meaning of words in some languages. So, it’s got this kind of phonemic use.

Brynn: Let’s hear what dialect coach Eric Singer has to say about creak changing meanings in other languages. This is from a video posted to YouTube from Wired and it’s called Accent Expert Breaks Down Language Pet Peeves. And we’ll hear more from Eric later in this episode.

Singer: So creaky voice actually has a linguistic function in some languages. In Danish, for example, the word un without any creak in your voice means she, but the word un means dog. So, you have to actually put that creak in and you can change the meaning of a word.

In Burmese, ka means shake and ka means attend on. You have to add creaky voice and it means something totally different. Otherwise, the syllable is exactly the same.

The Mexican language, Xalapa Mazatec, actually has a three-way contrast between modal voice, creaky voice and breathy voice. So, we can take the same syllable, ya, which with that tone means tree. But if I do it with breathy voice, ya, it means it carries.

And if I do it with creaky voice, ya, it means he wears. Same syllable.

Dr White: So, it’s not just this thing that is used by these celebrities in California. So, we know that it’s used by people in Australia, but no one’s really looked at it before. So, there are very, very few studies in Australian English on creaky voice.

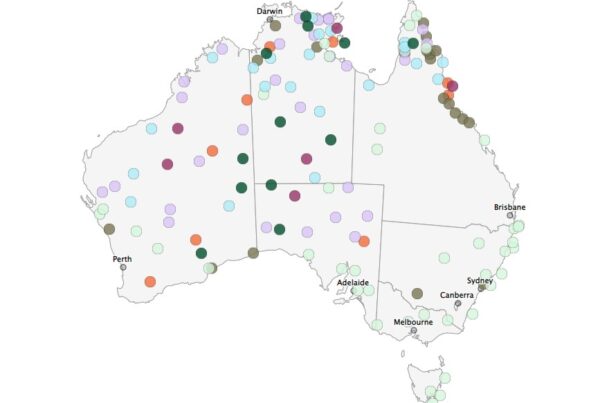

So that’s kind of where I started from. The data we used in my thesis was from the Multicultural Australian English Project. So that was led by Professor Felicity Cox at Macquarie University.

And the data was collected from different schools and different areas of Sydney that are kind of highly populated by different kind of ethnic groups. So, we collected data that was conversational speech between these teenagers. And I looked at the creak.

So, we’ve been looking at lots and lots of different linguistic, phonetic aspects of the speech. But I specifically looked at the creak between these teenagers. And I think the really interesting thing that I found was that overall, the creak levels were really quite similar between the boys and the girls.

It wasn’t, I didn’t find an exceptional mass of creak in the girls’ speech compared to the boys.

Brynn: Which is fascinating, because we, honestly, until I started looking into this for this episode, or talking to you, I just assumed that women, girls would have more creak in their voice than men. And then I was reading your data and reading the paper, and I was blown away to find out, wait a minute, no, there’s actually not that much difference in the prevalence of it. So, what’s going on there?

Why do we assume that it’s girls and women?

Dr White: There’s a lot of research in this specific area at the moment. Part of my thesis, I actually did a perception study about, so looking at how people perceive creak in different voices. So, it was a creak identification task, and they heard creak in low-pitched male and female voices, and high-pitched male and female voices.

And it could be something to do with the low pitch of male speech, generally. Post-creak is such a low-pitched feature. It might be that it’s less noticeable in a male voice because it’s already at this baseline low, so there’s less of a contrast when the speaker goes into creak.

Whereas if you’ve got a female speaker with a relatively high-pitched voice, you might notice it a lot more when they go down into the low-pitched creak. So that could be something that’s influencing this perception of creak as a female feature.

Brynn: Let’s give our audience an example of that now. This is from a YouTube video posted by Wired and dialect coach Eric Singer, as well as fellow dialect coach Eliza Simpson. We’ll link to this in the show notes.

Singer: One thing it’s hard not to notice is that most of the time when people are complaining about vocal fry and uptalk, they’re complaining about women’s voices, and especially young women. And it’s not just women who do this. Let’s try our own experiment, shall we?

Let’s take one sentence, the first sentence from the Gettysburg Address. I’m going to do it with some creak in my voice. Four score and seven years ago, our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Eliza, would you do the same?

Simpson: Four score and seven years ago, our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Singer: What did you think? Do you have different associations when you hear it from a male voice? Four score and seven years ago, than when you hear it from a female voice?

Simpson: Four score and seven years ago.

Brynn: We hear this creak in men’s voices, and we hear it in women’s voices. You mentioned that you were looking at multilingual Sydney. What did you discover about creak in multilingual populations?

Dr White: Yeah, so we, it was more, so the speakers that we were working with are all first language Australian English speakers. A lot of them had different kind of heritage languages, so either their parents spoke other languages at home, or they spoke other languages at home in addition to English. My research was more focused on the areas that the speakers lived in, so rather than their language backgrounds.

I think the most interesting thing we found was that the girls, so I said that there weren’t that many differences between gender, but the girls in Cabramatta or Fairfield area, so this is a largely Vietnamese background population, they actually crept significantly less than the boys in that area. So that was kind of an interesting finding.

And when we, like obviously we want to work out why that might be, so we had a look into the conversations of those girls, and we found that they were talking a lot about kind of cultural identity and cultural pride, and pride in the area as well.

So, talking about how they’re really proud of like how Asian the area is. And that they don’t want it to be whitewashed. So, we wondered whether for those girls, creak might be associated with some kind of white woman identity, and they were distancing themselves from that by not using as much creaky voice.

Brynn: Fascinating! Did you find out anything to do with the boys and why they, this more Vietnamese heritage language population, why they did use creak?

Did it have anything to do with ethnicity or cultural heritage or not? Or we don’t know yet?

Dr White: We don’t know yet. That’s something that needs to be looked into, but I did notice that they didn’t talk about the area in the same way. So it could be, yeah, it could just be the conversation didn’t come up, the topic didn’t come up, but it could also be like that relation to the area and their cultural identity is particularly linked to creaky voice for those girls.

Brynn: That’s absolutely fascinating. Did you find the opposite anywhere? Did you find that certain places had the girls creaking more than the boys?

Dr White: We did find that in Bankstown and in Parramatta, but we don’t know exactly why that is yet.

Brynn: It feels like there’s so much to do potentially with culture and the way that people want to be perceived, the way that they want to be seen. And I guess that could happen with choosing to adopt more creak or choosing not to adopt more creak.

Dr White: Yeah absolutely. It’s like a feature that’s available to them to express their identity for sure.

Brynn: And that brings us to something that you discuss in the 2023 paper that you co-authored called Communication Accommodation Theory and its relation to creaky voice. So, tell us what Communication Accommodation Theory is and how you and your co-authors saw it show up with creaky voice in this study about Australian teenagers.

Dr White: Communication Accommodation Theory is basically this idea that speakers express their attitudes towards one another by either changing their speech to become more similar to each other. So, if the attitudes towards each other are positive or diverging or becoming more different from each other, if these attitudes are potentially negative. So, this has been found with a lot of phonetic features such as the pronunciation of vowels or pitch.

So, speakers are being shown to converge or diverge from each other based on their attitudes or feelings towards each other. So, we wanted to look at this with creak because we had the conversational data there. Like it wasn’t, the data wasn’t collected with this in mind, but we thought it would be really interesting.

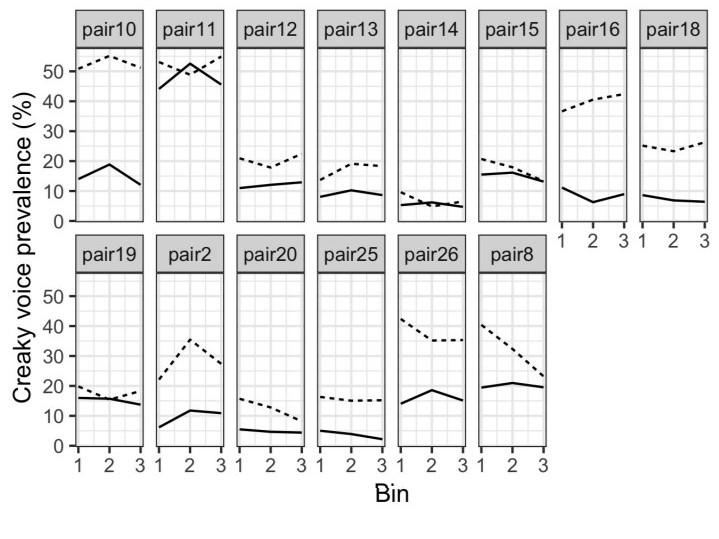

And we did find evidence that our Australian teenagers were converging in the use of creaky voice. So, over the course of the conversation, their levels of creak were becoming more similar to each other. We also found that overall, so we didn’t find an interaction between like convergence and gender, but we did find an overall finding of gender.

So that overall girls were more similar to each other in the use of creak than boys were. So, we think this might be some sort of social motivation based on research that’s shown that girls prefer to have a preference for fellow girls more than boys have a preference for solo boys. So, kind of a social motivation to converge.

Brynn: I’ve definitely seen that in research as well. And sometimes you’ll see sort of conflicting things. Sometimes studies will say, you know, oh yeah, girls and women, they always want to try to have that more like accommodative communication. They will socially converge more.

Other studies will say like, oh, we can’t really tell. But it is a fascinating area of research and trying to find out why, if it’s true, that girls and women do converge more.

Why is that? Do you have any personal thoughts on that?

Dr White: I wonder whether it’s like a social conditioning kind of thing. Yeah. That would be my gut instinct towards it.

Brynn: Tell me more about that. What do you mean by social conditioning?

Dr White: That girls, since we’re tiny children, we’re socially conditioned to be nice and to want to please people. It could be that that is coming through and the convergence.

Brynn: Yeah, and trying to show almost like in group, trying to say, hey, I’m one of you, let me into the group, sort of a thing. Yeah, which is so interesting.

What do you think the takeaway message is from your research into creaky voice?

What do the findings tell us about language, social groups, and especially in this case, the Australian English of teenagers? Because like we said before, I think a lot of times, creak is associated with the Americanisation of English, of language, sort of that West Coast Valley girl idea. So, what do we think that this all says about Australian English?

Dr White: I think it’s really hard to sum up a key takeaway from such an enormous part of my life.

Brynn: It’s like someone saying, like, tell me about the last five years in two sentences.

Dr White: Yeah, exactly. But I think my key takeaway from this is that creak is a super complicated linguistic feature. It’s more than just this thing that women do in America.

And the relationship between creak and gender is way more complicated than just, yeah, women do this thing, men don’t do it, or they do it less. So, it’s really important to consider like these other factors, other social factors, such as like language background or where the, like specifically in Sydney, where the speaker is, their identity as a speaker when we are looking at creak prevalence.

Brynn: I think that that’s the part of this research of yours and your co-authors that I found so interesting was this idea of creak being used or not used to show identity and not just gender identity, but also cultural identity, potentially heritage language identity, identity around where you live. So, I think that you’re right, it is more complicated than just saying, oh, don’t talk like that, you sound like a valley girl, you know?

Dr White: Exactly.

Brynn: There’s more about what it means to be a human in a social group in terms of creak than maybe we previously thought.

So, with that, what’s next for you? What are you working on now?

Are you continuing to study creak or are you onto something different? What’s next for you?

Dr White: I can’t stop studying creak. I’m obsessed.

Brynn: That’s fabulous!

Dr White: So, I’m actually currently working on an Apparent Time Study of creak.

Brynn: What does that mean?

Dr White: That is looking at, so we have this historical data that was collected from the Northern Beaches. So, kids, teenagers in the 90s interviews. And we have part of the Multicultural Australian English Project.

We collected data from the Northern Beaches. So, we’ve got these two groups from the same area, 30 years apart. And so, I’m looking at whether there’s been a shift in creak prevalence over that time, because people always say, you know, creak is becoming more popular, but we don’t have like that much firm empirical evidence that that’s the case.

So yeah, I thought it would be really interesting to see.

Brynn: Have you just started or do you have any findings that you can tell us about?

Dr White: I’ve just started. I’m coding the data currently. So yeah, watch the space.

Brynn: Watch the space because when you’re done and when you have some findings, I want to talk to you again, because to think that that’s what’s so interesting is examining it through time because you’re right, there’s so much that is in the media that goes around, especially talking about the export of American English and American ways of speaking.

I’ve talked in this podcast before about how even I as an American have been approached by Australians and they’ll talk about, you know, oh, we sound so American now. It’s because of all of the media and everything like that.

So, to actually be able to have some data to back that up would be incredible.

Dr White: Yeah, that’s really exciting stuff. I’m also going to Munich next year as part of the Humboldt Fellowship. So, I’ll be working with Professor Jonathan Harrington over there and looking at creak in German. That’s something that we don’t know very much about at all.

Brynn: Do we have many studies about Creek in languages other than English where it doesn’t denote another word?

Dr White: There are some, yeah, but it’s definitely, the field is definitely English-centric. So, it’ll be really interesting to see.

Brynn: That’s going to be so fun. I can’t wait to talk to you again. Well, Hannah, thank you so much for coming on today, and thank you to everyone for listening.

Dr White: Thank you so much for having me. It’s been a lot of fun.

Brynn: And if you liked listening to our chat today, please subscribe to the Language on the Move Podcast. Leave a five-star review on your podcast app of choice, and recommend the Language on the Move Podcast and our partner, the New Books Network, to your students, colleagues, and friends. Till next time.

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a