Celeste Rodriguez Louro and Glenys Collard, University of Western Australia

***

The histories and everyday experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia are etched in the landscape, the waterways and the voices of those who can speak and understand ancestral Aboriginal languages. They also thrive in post-invasion contact varieties such as Kriol and Aboriginal English.

Researching Aboriginal English through yarning

When our sociolinguistic project into Aboriginal English in Nyungar country (southwest Western Australia) started in early 2019 little did we know how much our fieldwork would enrich us. The premise was simple: head out into metropolitan Perth, set up the cameras and talk to people. Then use those recordings to figure out how Aboriginal English is changing. But there were so many questions. What model of research would be favoured and why? How should we collect our data? Who should we approach? What would people talk about?

It would have been reasonable to follow existing practice in sociolinguistics. But the canonical methods of the field are mostly based on industrialised, Western cultures and societies. How could we ensure that different ways of knowing would be incorporated into the project? How could we move beyond the Eurocentric mainstream to “hear the voices” of people historically pushed to the margins?

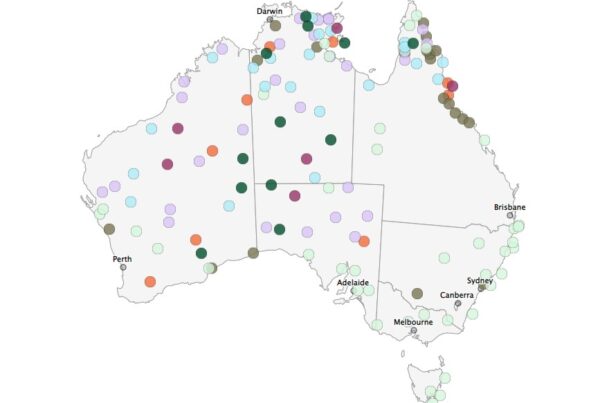

Data collection in a Perth city park (Photo reproduced with permission)

To the rescue comes Glenys Collard, a Nyungar woman, a native speaker of Aboriginal English and an experienced language worker whose input into the project changed the research forever.

Instead of a sociolinguistic interview, our data collection tool of choice was “yarning” – an Indigenous cultural form of storytelling and conversation. This type of conversation and storytelling is highly dramatic, using much gesture, facial expression and variation in tone and volume. The lack of pre-defined questions in the “yarning” format allowed speakers to remain in control of what they wanted to share while the cameras were on.

Recruiting research participants through listening

Instead of institutions, we headed out to meet people in their homes. But there was a catch. A significant number of Aboriginal people are homeless. In 2016, for example, Aboriginal people made up 3.7% of the total population of Western Australia but accounted for a staggering 29.1% of the homeless population in the state.

Glenys Collard was adamant these people’s stories should be heard, too. She led us into the streets and parks they call home. She reached out to them, she explained what we were doing and why. The photo shows Glenys Collard and the four women we spoke to at a Perth City Park in mid-2019. Glenys explains what was special about yarning with these women:

These yorgas [women] were too deadly [great], they could spin a few good yarns and they took after yarnin flat out about who they was, what they been doin. It was deadly. Celeste talked to them and they already looked at me so I gave them the ok with my eyes and closed mouth. The four of them were Aboriginal English speakers. I don’t think another researcher would have chosen them to speak with because of the area and the other people who were there. They all had a yarn and they wanted to share so we stay an listen.

They wanted to speak to us because of Glenys. She made the research safe for them. At the end of the session, Celeste asked Glenys why people – both in the park and elsewhere – had been so keen to speak to us. Glenys replied: No one has ever listened to them before.

These feelings are echoed by Dr Chelsea Bond, a Munanjahli and South Sea Islander woman and University of Queensland academic. Dr Bond explains that Australian society is founded on the non-existence of Indigenous people. She frames a lack of listening around police aggression. “Blackfellas are always speaking about police brutality – why aren’t people listening?”

Recording stories about police brutality and racism

Indeed, accounts of police brutality feature prominently in our collection. The corpus is replete with stories of racism and abuse.

Nita’s story stands out. We were outside a popular medical centre in downtown Perth when we saw her. Nita (a pseudonym) seemed upset, but she was keen to have a yarn so we set up the cameras. The microphones are on. Her twenty-something-year-old nephew is dead. Found dead at one of Perth’s private prisons. The police tells her and her family that her nephew killed himself. She and her family disagree: the bruises on his body indicate otherwise. She is sure her nephew was killed.

In another example, a prominent Aboriginal Perth leader spontaneously told us the story of a Nyungar woman who was evicted from her home in metropolitan Perth. When he arrived to try and stop the eviction, the woman’s heels were dug into the framework of the door, her little grannies (grandchildren) everywhere, police “by the mass”. He recalls seeing the police dragging the woman by the hair as her grannies looked on. He saw the Department of Child Protection officers take the woman’s grandchildren away.

Why aren’t people listening?

A young Aboriginal student we yarned with sums it up perfectly: “Someone who has grown up privileged cannot even fathom the idea of how we [Aboriginal people] might have grown up. It’s like a bad dream to them, like a nightmare. But that’s what we’ve lived, you know?”.

More than sociolinguistic samples

The voices in the stories we collected for our research are much more than high-quality linguistic samples of Aboriginal English. They are raw and real accounts of the community’s histories and everyday experiences. Our cross-cultural fieldwork allowed us to record the community’s voices using a culturally appropriate genre (yarning) and placing a community member, Glenys Collard, at the core. Her presence, experience and wisdom allowed us to move a step closer towards decolonising research into Aboriginal English. Importantly, her expertise allowed us to “hear the voices” of those rarely featured in sociolinguistic research.

Acknowledgement

This research is funded through a Discovery Early Career Researcher Award (DECRA) (DE DE170100493) and a 2019 Australian Linguistic Society Research Grant.

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a

Is there any chance of seeing the videos of the interviews you did as part of your research? I’d be really keen to see them.

I am ill when I see that things and I think this system first or after dead as patriarcal family. It is too much without of really modern life and don’t go up but return at old scheme. States, multinational holdings and big societies will destroy yourfelf because the difference are better for the life especial into the time of crisis.

Moorditjupiny nitja

very important research

Thank you, Miriam.

Very interesting to read about your research and the way you chose to carry it out, very inspiring, I will share with my students. All the best with the next stages, I look forward to reading more about your research.

Christine

Thank you, Christine. It is comments like these that make us want to do more, and more, and more. Tell your students we say hi, and to never stop fighting for social justice and inclusion. Every bit counts.

This account has given me goosebumps – for the sadness of wasted lives in custody and for not being heard, to the point people believe their lives and their stories are not worth being accounted for; but also for the joy that now their stories are being recorded in research and for the respect researchers have shown these people.

A couple of years ago I took a course in local language through the Sydney Festival. My teachers were Prof Jakie Troy and Auntie Jacinta Tobin; it was amazing to watch and listen to their ‘yarning’ while explaining language! Moreover, during classes, my mind would make so many connections with my own country, Italy, and its culture and with the Italian elders that have populated my life: the same love for story-telling, the same closeness to the land.

Thank you, Emanuela. I, too, feel connected to the storytelling I witnessed many times in my home country of Argentina. The yarning sessions were that and more though. As an outsider, it’s generally assumed that one cannot really fit in, that people might not trust you but this wasn’t the case at all. Glenys’ presence made all the difference of course, and it was an honour and a pleasure to be able to listen and take so much in. Thank you for your comments.

Thank you for this description! I was very inspired. Important work you do!

Thank you, Martha!

Thanks so much for sharing this. It’s amazing what you hear when you listen! Looking forward to reading more about what comes out of this project.

Thank you, Laura. We also look forward to our work together in the coming years (decades?). Thank you for your interest and support.