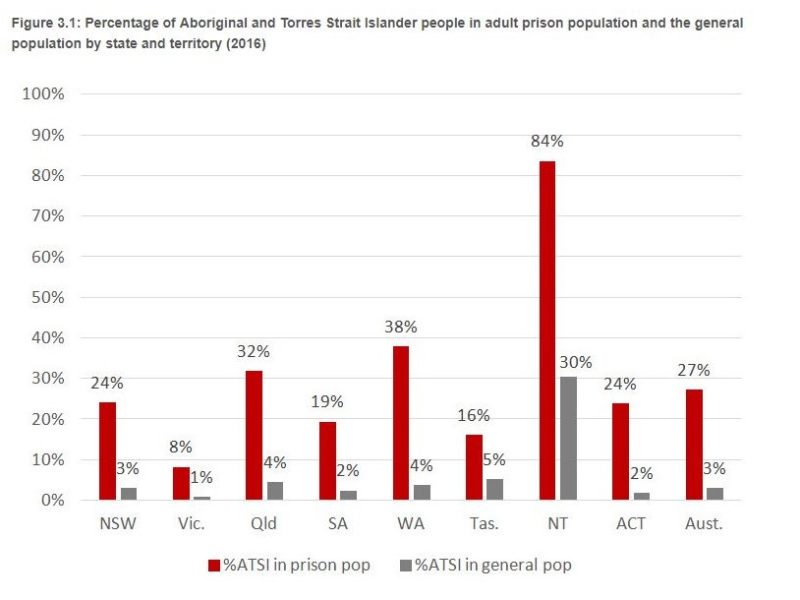

Indigenous Australians are imprisoned at much higher rates than non-Indigenous Australians (Source: Australian Law Reform Commission)

Note: This post was co-authored with Laura Smith-Khan.

Language on the Move mover-and-shaker, Dr Laura Smith-Khan, and I are just back from the 14th biennial conference of the International Association of Forensic Linguists at RMIT University in Melbourne (1-5 July 2019; program and abstracts here). This association, which goes by the acronym IAFL, brings together academics, police, lawyers, judiciary and language professionals, and offers stimulating research from scholars around the world, much of it revealing how legal processes and justice outcomes could be improved by better understanding language practices and mistaken beliefs about language.

The presentations by researchers, translators and interpreters here in Australia working with and on Indigenous languages were especially fascinating, and follows on from last week’s overview of IAFL research about law reform.

For international visitors, conferences in Australia can be an introduction to the customs of acknowledgement and welcome to Country. Attending this conference, we acknowledged that the conference venue sits on the traditional land of the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin Nation.

Amongst the many presentations relating to the International Year of Indigenous Languages, and specifically to Australian Indigenous languages, a highlight was Michael Walsh’s (University of Sydney) keynote. He spoke about his many encounters with the mistaken belief by non-specialists that, if an Indigenous person speaks any variety of English, then their participation in complex legal matters in English will be fair and unproblematic. Drawing on the extensive work on Aboriginal ways of using English by Diana Eades (who also presented at the conference), Michael talked us through a range of Englishes which are often conflated with Standard Australian English and Legal English. He also explained differing English discourses, making the provocative suggestion that sometimes ‘bad English’ can be to the claimant’s advantage and ‘good English’ to their disadvantage.

Also provoking reflection and discussion, Ben Grimes (Charles Darwin University) moderated a panel of speakers from the Aboriginal Interpreter Service, and presented his own ideas for timely advocacy by linguists to the judiciary. Linguistic evidence is highly relevant when assessing whether a defendant’s admissions were made reliably, as the new Uniform Evidence Act section 85 calls upon judges to consider. This could, and should, include greater and more technical consideration of the linguistic challenges faced by many Indigenous people in Australia who do not have Standard Australian English as their dominant language variety.

Aboriginal Ways of Using English, by Diana Eades

Some of those linguistic challenges – which become challenges in equal access to justice – were presented by Alex Bowen (ARDS Aboriginal Corporation). Alex examined transcripts of police giving the “right to silence” caution to Indigenous people (for the broader context of research related to this caution, see here). Police guidelines recognise a potential for miscommunication and therefore require police to give the caution in undefined “simple terms” and to ask people they are arresting to explain back what they have heard so as to check their understanding of the warning. This is important legally because the assumption that the right was understood then means any admissions are taken to have been voluntarily made. However, Alex’s analysis revealed a great variety of apparent mistakes about the caution having been understood. Problems included conversational sequencing affecting how suspects interpreted police language; chains of paraphrases producing confusion, especially relating to the meaning of conditional clauses; failure to add information; and police not providing clear feedback to suspects about whether or not they have demonstrated an accurate understanding of their rights. Alex made the plausible suggestions that it would help if police announced the topic, i.e. explained that what they were about to do was to give a caution and test whether it had been understood, rather than to start an interrogation. His recommendations included:

- That people who lack familiarity with mainstream legal culture and institutions be educated about the legal system outside the interview room

- That police start with a clearer text in plain English if they are going to explain the caution (see CORG 2015 recommendation 1)

- That police develop and evaluate a process for explaining and testing the caution in arrest conversations

Problems with the police caution underpinned years of litigation relating to manslaughter for which Mr Gene Gibson, an Indigenous man from Kiwirrkurra in the Gibson Desert, was arrested in 2010. After years of imprisonment and legal appeals, Mr Gibson was finally released in 2017, when the WA Court of Appeal found there had been a miscarriage of justice. Mr Gibson’s first language is Pintupi and his second language is another Indigenous language, Kukatja. The court found that Mr Gibson’s initial guilty plea had not necessarily been “attributable to a genuine consciousness of guilt” but resulted from mishandled language barriers and mistaken assumptions about language.

It was encouraging to hear at IAFL that the expert evidence of Professor Diana Eades had been considered by the courts and played a key role in Mr Gibson’s eventual release. Diana’s presentation explained language problems which arose in the initial police interview. In this part of Australia (Western Australia), police investigations involving Indigenous suspects must include an “interview friend” to provide support. However, for Mr Gibson, the police misunderstood the difference between an interview friend and an interpreter, deciding not to call an interpreter and instead to rely upon the interview friend to interpret between Indigenous languages and Standard Australian English. Rather than relaying the information that Mr Gibson was free to choose not to answer police questions, and that, if he did, he risked incriminating himself unnecessarily, the interview friend advised Mr Gibson that he must answer the police questions. Not knowing the relevant Indigenous languages, the police officers did not pick up this problem at the time.

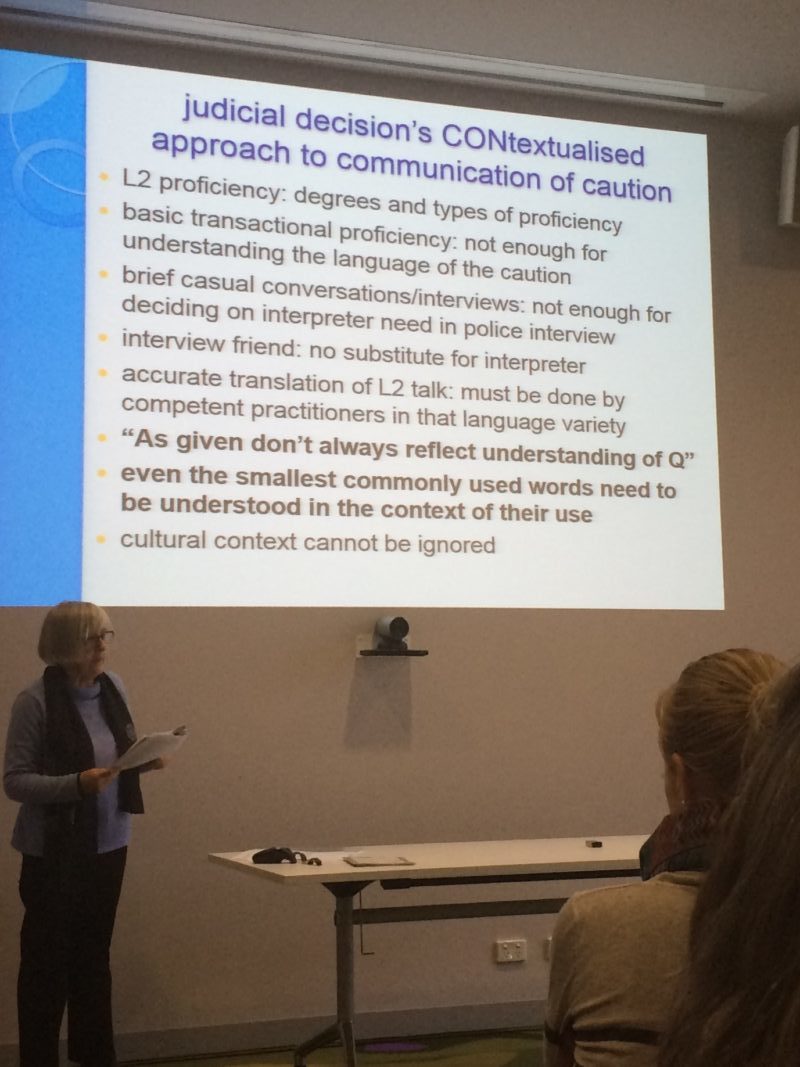

Diana Eades’ recommendations for basic linguistics instruction for police and lawyers

Diana used this case to illustrate two approaches to language: one in which meaning is (mis)understood as independent of context and one in which meaning is contextual. The de-contextualised approach is the source of many language-related injustices in legal processes, from taking simple words like “yes” on face value as consent or affirmation, to misunderstanding the different linguistic demands of an interview compared with a casual chat about the footy and therefore not arranging an interpreter. That Mr Gibson finally won his release was due to certain judges, unlike the police, understanding that meaning is contextual (see e.g. the 2014 judgment). Diana concluded with the recommendation that the points listed on the slide be taught to police and lawyers (see image).

Widening out to look across multiple cases of unreliable admissions of guilt, David Moore (University of Western Australia) reaffirmed that there are high-stakes linguistic “false friends” between Central Australian Englishes and Standard Australian English, e.g. “kill” and “rape”, which can lead to false confessions from Aboriginal defendants.

Natalie Stroud (Monash University) focused on another type of court, the Koori Court of Victoria, which is designed to provide a culturally sensitive forum for Indigenous offenders and give them a voice in the criminal justice system, including by integrating community Elders into “interactive sentencing conversations”. She highlighted that the introduction of video conferencing is impacting on their inclusion, narrowing the conversation back to a Magistrate-defendant dialogue.

These presentations about legal processes were complemented by research on phonetics. For example, Deborah Loakes (University of Melbourne) has been building up the technical description of the phonetics of two Victorian varieties of Aboriginal English, and the variations within them, which could better assist decision-makers in the legal system to identify speakers of these varieties and specific inter-lingual communication issues such as mistaken identification of a speakers’ background.

Attendees also heard from experts from beyond linguistics, for example lawyers from the North Australian Aboriginal Justice Agency presented the case for using cultural brokers instead of legal interpreters in Government service delivery to remote Indigenous communities. Similarly, Dima Rusho (Monash University) described the innovative collaborations of legal professionals and Indigenous community members in the Northern Territory to develop translations that draw on Indigenous conceptualizations to improve the understanding of key terms in legal processes.

In this International Year of Indigenous Languages, these researchers are helping us all think through the links between the minoritisation of Indigenous languages and the systematic inequalities faced by Indigenous people in Australia’s (and other nations’) legal systems, providing ideas and impetus for reform.

References

Bowen, A. (2019). ‘You Don’t Have to Say Anything’: Modality and Consequences in Conversations About the Right to Silence in the Northern Territory. Australian Journal of Linguistics, 39(3), 347-374. doi:10.1080/07268602.2019.1620682

Eades, D. (2013). Aboriginal ways of using English. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press.

Eades, D. (2018). Communicating the Right to Silence to Aboriginal Suspects: Lessons from Western Australia v Gibson. Journal of Judicial Administration, 28(1), 4-21.

Smith-Khan, L. & A. Grey (2019). Lawyers need to know more about language. Language on the Move.

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a

I am glad that I encountered this reading since this dilemma is also prevalent in my country, which is the Philippines. With these situations, it is just apparent that the English language is being weaponized against the indigenous and poor people who couldn’t afford to study the language. English may be considered the lingua franca however, it is undeniable that there is an English-centrism that can divide the masses.

When the stakes are high in the context of legal matters, it becomes increasingly evident how big a role communication and understanding legal language plays in one’s outcome. It is not safe to assume that someone with functioning proficiency would understand legal proceedings or police warnings. It is important that those working in law enforcement take contextual meaning into account for fair social justice.

This post has discussed the effects of cultural and linguistic differences that affect legal procedures in a country. Translation can often be hard when it comes to legal discourse as well as other discourses like food. Experts need to be aware of the consequences of misinterpretation of information. In the case of indigenous individuals authorities should follow the procedures to ensure no injustice is done towards the accused. Linguistic competence is only one aspect. Just because an individual is proficient in a language doesn’t mean they will understand everything in the context of legal discourse.

Thank you for your sharing from the concert. This post is really full of factual information. In my opinion, legal issues and terminology are a problem facing language learners as well as indigenous people because of the English language, the government should try to integrate indigenous people into society in order to alleviate the problem. As for language learners، vocabularies are very difficult because they are not used outside the courts and police stations. Therefore, the presence of interpreters is very important.

Thank you for this report. It is truly inevitable that second language learners at any level of proficiency all face certain particular linguistic difficulties. It reminds me of my teacher’s popular term “native-like accent” back then when I was a sophomore student. My teacher’s belief shows that a foreign language learner can fluently and beautifully perform their speaking skill to some certain extent but never can sound like a native speaker due to some constraints, especially, the mother tongue influence.

I used to be a translator of English to Bahasa Indonesia and I always found legal discourse is the hardest to understand. And I agree with the idea of familiarizing the mainstream legal culture especially the language to those who are likely to be in contact with the interpretation of the language. As in my case, it might be highly recommended to the company to provide some kinds of workshops and training from the expert of law to educate their translators and interpreters as this can also improve the quality of the final translated text.

Compared with English, indigenous languages are not popular and do not have many benefits than English. However, not all the indigenous language speakers have good English skills, so indigenous languages exist and actions should be taken to help indigenous language speakers to use their rights.

Hi Alexandra,

Thanks for sharing this interesting article about the language disadvantages of the indigenous people in achieving equal access to justice. This is a surprise to me as I used to believe that law is fair and scrupulous. However, the challenges to people speak the indigenous language in understanding the legal language are likely to be neglected. Even with an interpreter, the information would still be misunderstood with a high chance, if the interpreter does not have a comprehensive understanding of the language differences between the indigenous language and English.

I really enjoy your report about the conference from your post. I do believe that although L2 English speakers possess a certain level of proficiency in English, they still encounter various problems related to the legal cases. Firstly, there would be many legal terms which are complicated to the readers who are L2 speakers of English. Secondly, some participants from the court still have issues with listening and speaking in English in the court. Therefore, I think the interpreters are very important in those cases. To protect the language diversity, the interpreters also play a key role in encouraging the indigenous people to maintain their language, and accordingly their culture.

I really enjoy your report of the conference from your post. I do believe that although L2 English speakers possess a certain level of proficiency in English, they still encounter various problems related to the legal cases. Firstly, there would be many legal terms which are complicated to the readers who are L2 speakers of English. Secondly, some participants from the court still have issues with listening and speaking in English in the court. Therefore, I think the interpreters are important in those cases. To protect the language diversity, the interpreters also play a key role in encouraging the indigenous people to maintain their language, and accordingly their culture.

Thank you for sharing this article. I had worked as an interpreter in the telecommunications company, so I understand the importance of accuracy in interpreting. It is really not professional to incorporate a personal position or not to convey the exact meaning when interpreting, not to mention interpreting for interrogation in criminal cases. Such cases of unreliable admissions of guilt reflect the difficulty that indigenous people may have been experiencing when engaged in social and cultural activities.

English as a dominant language is used as the official language in many countries and regions such as Australia and New Zealand. However, in these countries and regions, indigenous languages are also widely used by local residents in their daily lives. As the article says, indigenous languages are at a disadvantage compared to English. At the same time, not all speakers of indigenous languages have good English skills, which leads to the difficulties of indigenous language speakers who are not good at English in many contexts. Therefore, I agree with the author’s point of this article. Considering the difficulties of these speakers and their rights, the necessary measures should be taken.

Whenever I heard the name “Aboriginal”, I tend to link this to disadvantages or inequality in life. It upsets me a lot. Living under the same sky, Aboriginal people speak a different language and get in a lot of troubles when communicating with other Australians and raising their voice. In this post, an Aboriginal person was arrested due to his lack of standard English, his mishandling language barriers and his inability to communicate his message with the police force. It is a scary story that I’ve never wanted to get involved in. If only Aboriginal people also learned Standard Australian English and Legal English, they would not get involved in such injustice and suffer inequalities in life.

In Australia, most Indigenous people identify strongly with a traditional language identity. The tribe with which they identify is a language group and in the great majority of cases, the tribal name is the language name. It is important to emphasize that Australia is not a monolingual society. Since British settlement, English has been the main language in Australia. The importance of learning and speaking English competently for all Australians is not disputed. However, it is equally important for all Australians to recognize the several hundred unique Indigenous languages that were spoken for tens of thousands of years in Australia. These languages have not always received due recognition in the past.

Thanks for sharing this interesting article about the indigenous people and problem they have been facing due to no access to English language. This story make me sad because indigenous people are deprived from the getting justice in Australia. Nowadays English language became a dominant language all over the world and indigenous languages are overwhelmed by English language. This article reminded me the case of Nepal, in Nepal there are many indigenous community, among them Raute is an indigenous community who cannot speak even Nepali language and many time they became victim of justice in Nepali justice system. Indigenous people are facing injustice because of language in Nepal as well.

It is quite scary to think that a lack of opportunity to communicate the exact message clearly can bring one into gaol. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples have the disadvantage of (often) not speaking Standard Australian English (SAE); however, this may happen to many other groups (think immigrants or some ethnic groups) too. I feel like the system is set up in a way that makes it difficult to understand what authorities wish to communicate so one’s responses cannot be so precise. While I believe I have a very good command of English, I have found myself in a situation when I had to think really hard in order to understand the message. It is usually the result of complicated language that is used instead of plain English. It was in one of our lectures on communication and accessibility when we learned that important messages should be written in the language that can be understood by a person having a reading age of a Year 3 student (around 8 years old).

I found that this article is very interesting, and it lights me up. To be fair, I think the language, using in the legal process, is already difficult by itself. And that can be very hard for indigenous people who do not share the same language. Since the language is very sensitive in this matter, it is very challenging to make both languages be equal when it comes to the legal process. In order to improve cross-language in the legal process, we still need more researches to support this, not particularly in aboriginal languages, but in other languages as well.

Thank you for your sharing. Before reading this article, i never consider that language barriers can affect justice. The IAFL conference claims that language barriers can make a misunderstanding in legal practices between Australian police and Indigenous people. It is difficult for a person whose first language is not English to be familiar legal system in a new country, especially at courts. It is detrimental for Indigenous people, because they do not know how to protect themselves and stand up for their rights in limited English. In my opinion, constitutions need to consider the difference of culture and linguistics in Indigenous people, and they can provide interpreters for police interviews. However, Indigenous people also need to study more about language differences to avoid misunderstanding.

This report helped me understand how indigenous people with language barriers can be at a huge disadvantage in the face of justice.This surprises me. In my mind, I always believe that justice should be the most fair and impartial place to judge by evidence and facts. However, the experience of indigenous people has made me rethink the relationship between language barriers and fairness.Inferior English may lead to misunderstanding and may affect the administration of justice, but it can also be avoided by other means such as having a professional interpreter to translate.

Thank you for the post, it gave me a different perspective of linguistic justice. It is heart-breaking that seeing indigenous people in Australia face such a linguistic challenge. The challenge influences not only in their communication but also on their innocence. I agree with Alex’s suggestion that the police officers should explain the laws with plain English and test if they truly understand rather than interrogate directly. Many people argued that a language is a tool for travelling or communicating, I am convinced that a language also plays an important role to support underprivileged groups after reading this article.

Thank you, Alex, for a great post. I have learnt about Gene Gibson’s case previously in a conference I have attended, and it made a big impact on me. It is quite sad that still in 2019 the rights of minority groups (such as Aboriginal Australians) are not fully recognized. What I mean by “rights”, is the prerogative to be recognized as speakers of other varieties of English. Legal English can be quite arduous to understand for anyone, even for speakers of Standard varieties. Expecting Aboriginal Australians who speak a creole variety of English, for instance, to be able to comprehended complicated legal language in situations such as an arrest without any further support seems quite unfair. I believe that scholarly advocacy plays a crucial role in bringing awareness about linguistic differences among people, thus posts such as this are extremely helpful to spread said awareness.

This post discloses a distressing fact that Aboriginal Australians who are not standard English speakers are most likely to get disadvantages when involving in legal processes. It is also a fact that suspects who are non native English speakers have great challenges in full comprehension of Miranda rights due to lack of sufficient English proficiency, which often leads to self-incrimination and negative consequences. As Miranda warnings includes many infrequent terms/vocabulary words and some complex sentence structures, it is difficult for defendants with limited English proficiency(non native speakers ) to completely appreciate the exact meanings of these warnings/rights. To make it worse, unprofessional interpreters without sufficient legal knowledge often fail to consider the pragmatic factors of legal context, resulting in inaccurate translation. Those negative factors cause the suspects not understand their legal rights and tend to make confessions that could be used against them in court. To guarantee non native English speaking suspects’ legal rights, forensic linguists and professional interpreters with sufficient legal knowledge should be included in case processes such as interrogation or in court in order to protect defendant’s legal rights.

Thanks for sharing the cases and the ideas you gained from the conference. From the your blog post, it can be seen that due to the linguistic barriers, indigenous people in Australia do not have equal justice status as people who can speak standard English. Alex Bowen’s police language impressed me a lot. If police can not use simple English to investigate and fully understand suspect’s answers, the investigation process has no sense. As Alex suggested, police should clarify the basic principles that will be used in investigation to indigenous suspects to ensure their justice rights. Besides, Mr. Gene Gibson’s case is impressive as well. He was arrested because his guilty plea did not meet the requirements of effective plea. The main reason is that he is an indigenous person who cannot use standard English to clarify. As many suggestions listed above, it is extremely necessary for Australia police, lawyers to face the inequality justice status of indigenous people. Interview friends and special translators should be introduced into Australia justice system to make a change.

Thank you for your sharing of the IAFL conference content, especially how language barrier has resulted in numerous misunderstandings in legal practices between Indigenous groups and the Australian police. Misinterpretation of speakers’ ideas causes much trouble in our daily lives, and definitely this could produce even more serious consequences in legal situations such as at courts or police interviews. It is essential that agency leaders should develop a systematic procedures of acts in dealing with Indigenous people which address closely linguistic and cultural differences between two sides. Besides, assistance from a third party which is translators should be sought as to minimise the mismatch in oral or written communication for the rights of Indigenous community.

Hi everyone,

I think that the government should look in to this process as an opportunity for improvement as I can see that Australia is slowly integrating the Aboriginals and Indigenous tribes in to the modern society. The judiciary system should work with the Aboriginals and subject matter experts in communications to develop a program where the “interview friends” would be able to translate the human rights effectively to the Aboriginals so that they are aware of all their rights and that everything that they say or do can be used against them. Mr Gibson’s example should serve as a starting point in developing and rolling out this program.

This article provides an interesting overview of the issues that many Indigenous people in Australia face in seeking equal access to justice in Australia’s legal system. Even for people with a good grasp of standard Australian English, for those not familiar with Australian legal culture and language, it can be very difficult to understand what’s going on. Without professional legal support for Indigenous people that includes interpreters who can understand the relevant Indigenous culture and language, its no surprise that there has been misunderstandings. Mr Gibson’s incorrect conviction in particular is an unfortunate one that could have easily been avoided had the police and legal system better recognized the link between language and context, and ensured that he had sufficient interpreting support. At the very least, its encouraging to see the work done by language researchers at the biennial IAFL conference to raise awareness of these matters and involve police and lawyers to ensure the link between language and context is better understood and respected moving forward.

It is obvious that culture and context shape the meaning of language. As the law enforcers are mainly equipped by their professional knowledge but the language proficiency, the role of interpreters and cultural breakers are essential in such situations. The information and message that ones’ want to deliver should be translated depending on both indigenous language and their culture to fully achieve their meaning. Furthermore, enacting a law should also use general language combines with language for specific discourses for non-indigenous people to understand.

It’s quite a surprise to me that there was such a serious legal case but the importance of interpretation was overlooked. Besides from the carelessness of the police, the ambiguous wording like “interview friend” in legal documents would need to be considered. I agree with the suggestions of Professor Eades that meanings need to be understood in context and variations of English need be taken in account when presenting linguistic evidence.

Hello, Alexandra. Thanks for your post about how language barriers lead to indigenous disadvantage. I agree that language barriers can cause misunderstanding and even let people under worse situations, especially regard to legal process. Mr. Gibson was arrested and this guilty proceeding occurred resulted from mishandled language barriers and mistaken assumptions about language. Because this person cannot speak Standard Australian English to clearly express facts to police and lawyers. To avoid misunderstanding, it is important to offer professional interpreters who can understand indigenous language to explain terminologies to the Aboriginal people and communicate with them during the legal process.

Thank you for an interesting post. It is always sad to know about these indigenous people’s unfair treatment in life. It is unfair that different cultural values that one associates his or her action being guilty in court. However, I am not saying that there should be cultural exception when it comes to serious crimes. I am not a professional in legal law but I think something needs to be done when there are different members of people in a society. Japan will need to consider something to be done with their law suit when there will be more and more immigrants in the near future.

I have seen up-close the struggles of someone who tried to comprehend the legal system. My uncle speaks English as a second language and is not highly proficient in it. One time, he was charged with speeding and sent to a court hearing. He had to rely on a lawyer who was not proficient in my uncle’s mother tongue, so there was a broken link between the two people. Nevertheless, my uncle placed his faith in his lawyer even though he did not understand any of the court proceedings. I cannot even begin to imagine how many families have experienced this and the struggle to find someone who can understand their side of the story. Especially with the Aboriginal people, they watched this land grow to the society it is today. And yet even they are susceptible to disadvantages such as language barriers. The vulnerable communities deserve to feel they are in safe hands, and to have professional legal staff who comprehend the minority’s first languages.

This article speaks on the deep cultural and racial bias that is unfortunately embedded in western societies. Even native speakers who are highly-educated, even in an adjoining discipline similar to law, have difficulty discerning and comprehending the linguistic complexities and density of legal language. How can anyone expect a second language learner or anyone with very little experience in the standard language and who were socialized in a very different culture, to accurately comprehend the nuances of the justice system? This is a global issue for many minorities and multilingual and bilingual citizens who are unfamiliar with such linguistic complexities of the standard language in which crime is persecuted. The injustices that these individuals encounter is heavily compounded by cultural and racial bias in accordance with lower socioeconomic status, educational inequities, and social injustices.

I believe a lot of aboriginal people in many countries face the same problem, not just in Australia. In Vietnam, aboriginal people used to never wear a helmet while driving a motorbike which is totally against the government traffic laws. However, it is impossible to fine them because they may not have money to pay for their mistake, and on top of that they are not willing to pay that money because in their perspective, they have no idea the definition of laws or government is or why they have to wear the helmet when they don’t need to and don’t want to. To tackle the situation, policemen instead of strictly fining ones who violate the law, have pay a visit to the aboriginal area, making friends with these people and explain for them why wearing a helmet is a good thing that they should do.

Before reading this blog post, it had never occurred to me that a halfway decent level of English competence could in certain cases be actually worse than poor English competence. Indeed, in such fields as legality, the abounding jargon might cause comprehension difficulty for someone whose first language is not English, putting them at risk of accidentally forfeiting their legal rights and in turn leading to more serious implications. Therefore, efforts to ensure better communication between suspects and police officers, lawyers, etc. are crucial to the administration of justice.

The article mentioned in this article is very interesting. I have had such a personal experience. Before I first came to Australia, I heard about the story of many Chinese people being investigated and even repatriated at customs because of their poor English. So when I first came to Australia, I was very nervous. At that time, I brought three boxes, and then the customs staff asked me to open the box for inspection. I brought some specialties from our hometown, some of the materials used to make hot pot. But at the time, it was difficult for me to explain to the staff what the materials were made of, and whether they contained animal fats and so on. My ambiguous expression attracted the attention of the customs officers, and eventually my materials were taken away by the customs. Although this example does not represent the impact of “inferior” English on judicial justice, it also reflects that low English proficiency can easily lead to misunderstanding. When these misunderstandings occur in more serious situations, it is easy to cause huge problems.

I have read many comments and it is said that language barriers can lead to misunderstanding and further wrong decision and it can be even worse when this is related to legal activity (namely personal fate). I personally find this conference is very fruitful because it covers very specific topic and it is discussed in many facet by a variety of scholars, professionals pertain to this field. In my view, English terms related to laws and legal system are so rich and there are words can be puzzled because they have very slight difference in meaning. The suggestion that the interpreters specialized in legal system should work in the sensitive situations. Fortunately, Mr Gene Gibson was released after it was revealed that there had been a misunderstanding and ambiguity related to investigation. Nevertheless, this case has presented that there likely have been many cases similar to Gibson and weren’t revealed the truth.

It can be said that language barriers can trigger an array of drawbacks for people in any circumstances, especially the circumstance happens in the legal context. In this article, Mr. Gibson was arrested because of lawsuit concerning manslaughter; however, the guilty proceeding occurred due to linguistic hurdles and misinterpret assumptions related to language. I think although people communicate the similar language, there are different terms in each field. Besides, obtaining a wrong comprehension about a word may lead to negative misunderstanding; hence, people should contextualize what one another expresses orally.

It is so serious if language is misunderstood and becomes barriers, especially with regard to legal. As can be seen from the article, Mr. Gibson – an indigenous person – was arrested due to the litigation relating to manslaughter, but this guilty plea resulted from mishandled language barriers and mistaken assumptions about language. Because he is an indigenous person and he does not have Standard Australian English, and the police did not invite an interpreter, hence, they misunderstood each other. Therefore, it seems that to make equal and balance, for example, in legal processes, it is important to enhance the understanding key terms by developing translations that draw on Indigenous conceptualizations. Moreover, cultural context is said not to be ignored when considering an issue.

Language barriers can put a person at his disadvantage in any case, and that could be even worse if the situation is related to legislation. Let just imagine someone, as a new immigrant, even if he can be fluent in that country’s language, it is still difficult and takes time for him to get familiar with the new legal system. Then how Indigenous people, or Aborigines with limited English proficiency and different culture could defend themselves when needed. However, recently more and more researchers have given much effort on these cases to shed light on language disadvantage in law system by providing several recommendations.

Hi Alexandra, thank you for your post!

It is interesting for me to know what happened at the conference from your detailed report.

I think that the indigenous people’s difficulties in communication with outsiders such as police, lawyers, authorities stem from their education. in other words, what kind of English they learned, how often they used English to communicate with the outsiders, or how effective it is in those contexts is worth critically examining. However, education policies are closely connected with the political process, so the task here is handed to the government. My suggestion is that the policies should be specialized and specific with the case of the indigenous people because of differences in culture and tradition.

Dee

The sad reality of indigenous cultures once again being forced to the rule of the occupiers. Why should the indigenous peoples even have to learn English at all? Secondly, I don’t think simplifying the English language will do much and it’s almost patronising even though I do understand the intention. It is the communities themselves that ultimately need to facilitate the handling of such cases and that would require time and training among other things.

This article helps more gain more insights into challenges Indigenous people have to face in the society, especially Australia in which they have to both maintain their own cultural identity, language and values and immerse into the modern society. This issue is genuinely sad and moving in the way that a person’s life can be ruined due to linguistic barriers and misunderstanding. It is relieved that a number of people including professors and experts mentioned in this article made great efforts to fights for the rights of the Indigenous so that they may not feel inferior to other people of majority.

How moving and informative this article is!

It is a tough place to be when your heritage and language background work against you in a legal sense. As an interpreter, I understand the importance of empowering a person with expression when at a disadvantage. Impartiality is a major ethical aspect of interpreting and forbids us to give advice. We are there to bridge the language barrier and in my opinion, would not continue interpreting if confusion and miscommunication prevailed in an interview. In this case, the interpreter would bring to light the accused is not of understanding of the situation and would ring alarm bells. This says to me that interpreters as useful as may be, are not the answer to a more just system. It must go beyond, linguistics is an avenue to keep exploring and educating front line police on the contextualization of language is paramount.

I’ve learned so much from this post about legal discourse, especially the legal rights of Indigenous people. I can’t agree more that context plays a significant role in communication and sometimes it is the deciding factor to the meaning of words. I have seen many legal cases, especially in my home country Vietnam, where contextual meanings are blatantly ignored which results in people being incriminated and jailed for the wrong reasons. When arrested by the police, most of the time they are stripped of their own rights to understand and to confirm their understanding. It is impressive how many representatives of the government and the law (like the judge you mentioned) today understand how a person’s words must be understood in context. This way, social justice can little by little be regained for those who are legally weaker.

Thank you for sharing such an interesting post!

I have always had a great interest in the relationship between language and the legal system. I found the case of Mr Gene Gibson one of unimaginable injustice. It seems almost unbelievable that such a mistake can be made in the legal system, especially the reliance of an ‘interview friend’, and not a competent, trained professional, for relaying crucial legal information to Mr Gibson.

Knowing that there are ‘high-stake linguistic false friends’ between different varieties of English that could potentially lead to false confessions in crimes such as rape and murder, is downright frightening. I believe that simply having this awareness of the current linguistic inequalities between the Australian Indigenous population and the Australian legal system, including police, should be enough to warrant change and reform in order to prevent the next injustice.

Personally, I think even though people speak the same language, they should contextualise what one another says. The reason is, each person coming to the interaction has his/her own background of language and of using the language. Let’s take the context of doctor-patient interaction as an example. Even though they are both native speakers, the fact that the doctor’s familiarity with technical terms and likewise, the patient’s unfamiliarity with clinical jargons calls for the need to contextualise the language. Like in the legal field, the wrong use/understanding of a word to describe the health condition may result in inappropriate treatments. Therefore, I don’t think that language should be independent of the context.

The story of miscarriage of justice sounds extremely sad and unacceptable. Indigenous people, who had originally lived in the land are forced to follow rules that are made by non-indigenous people and these rules might not necessarily suit their convention, culture or values. I feel more things than speaking English plainly and slowly in arrest conversation etc should be done for indigenous people. Not to say changing laws so that they can be accepted by indigenous people, I think efforts to make the rules understood by everyone should be made.

I have to admit that language is inherently larger than just meaning, but also contextualization in which language contains potential meanings. Obviously, when we solve a math exercises, we just need the conclusion of rightness, a specific figure. But in a legal case where there is existence of more than a common language, more is necessarily needed, especially in legal linguistic performance. Perhaps because English have countless relatives such as English varieties and World Englishes, etc. or English originated from the Latin alphabet so legal English became a nightmare to some people who does not belong to legal English like me. I totally satisfy that law symbolizes justice in human beings’ society. However, law is not right or wrong; so is language. All of them depend on contexts. When legal aspects need remedies from linguistics, there is a necessity for lawyers to have deeper insight into linguistic aspects and vice versa. Therefore, we cannot deny the crucial role of cultural brokers as well as legal interpreters. By this way, there is no one that can insist that there is just a demand in intelligibility in conversations, but we also have to thoroughly consider avoiding misinterpreting because of lack of cultural knowledge about a civilization which can lead to a miscarriage of justice, which in turn opposes to human equality.

*I thoroughly enjoyed reading your blog – thank you very much for the poignant insights!

Overcoming Indigenous Australian language barriers calls for an overhaul of police training that entails cross-cultural communication, cultural awareness and disability awareness.

Although the right to an interpreter is an Australian legal obligation for police who will conduct questioning or for a court procedure or the criminal justice system as a whole, the instances where police are aware and understand that 90% of Indigenous suffer from deafness and cannot possibly understand what is being communicated to them is often overlooked.

The well known High Court case of Ebatarinja v Deland [1998] HCA; (1998) 194 CLR 444, illustrates that deaf, mute and illiterate defendants cannot have a fair hearing or fair police questioning when they cannot understand nor follow legal proceedings. Since 1998 the Northern Territory Government has pursued the incorporation of the police having a manual that sets out the Anunga rules derived from the R v Anunga (1976) 11 ALR 412 case that an interpreter is a requirement for police questioning.

The Northern Territory Government has also commissioned AIS to produce an app which translates the police caution into eighteen most commonly spoken Aboriginal languages. The app is available on all police iPads.

However, interpreters remain essential for Indigenous Australians to gain better communication and justice in an already challenging legal system for them. Recently, the international Commission of Jurists Victoria suggested that interpreters standards should be based on the Canadian case R v Tran 2010 SCC 58, [2010] 3 S.C.R 350. In R v Tran, the decision of continuity, precision, impartiality, competence and contemporaneousness shows the urgency in which interpreters with legal training who can capably interpret legal contexts is of ongoing importance for Indigenous Australians.

Here is it obvious that linguistics is extremely important to bring to the foreground of the Australian legal system. Linguistics has been undervalued thus far, but it is a solution for miscommunication as is professional interpreters being proficient in both Aboriginal languages and the language of the Australian law and its legal context.

Australian Government, Australian Law Reform Commission: Pathway to Justice Inquiry Into the Incarceration Rate of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples (ALRC Report 133) – Access to Interpreters (11.01.2018)

Campbell, L. (2018). Interpreters, AUSTLII Communities – http://ntlawhandbook.org/foswiki/NTLawHbk/Interpreters

Pether, P. (1999). ‘We say the Law is too important Just to Get One Kid’ – Refusing the challenge of Ebataringja v Deland and Ors [1999] Sydney Law Reform 4

Thanks, Christina, for your insightful comments. I was wondering where you got the statistic regarding deafness? I have heard that there are higher rates of hearing impairment reported in some Indigenous communities, but 90% deafness is quite a surprisingly high figure and am wondering how it could be generalized/calculated across all Indigenous people. Also, I’m not sure whether “suffer” is the best word choice to describe someone who is deaf or who has a disability, but that is a separate discussion.

More generally though, you touch on an important point that was raised by a conference participant in our discussions in between presentations: that not only are Indigenous people highly overrepresented in Australian prisons, disability prevalence amongst prisoners is also really high, including a range of disabilities that may impact communication or understanding unless they are properly accommodated. This was a consideration that did not feature particularly heavily in the conference – at least in the presentations I was able to attend – and merits greater acknowledgement, given its potential implications for access to justice.