This episode of the Language on the Move Podcast is the 6th and final episode of our series devoted to our new book Life in a New Language, which has finally come out!

To read a FREE chapter about participants’ experiences with finding work head over to the Oxford University Press website.

To read a FREE chapter about participants’ experiences with finding work head over to the Oxford University Press website.

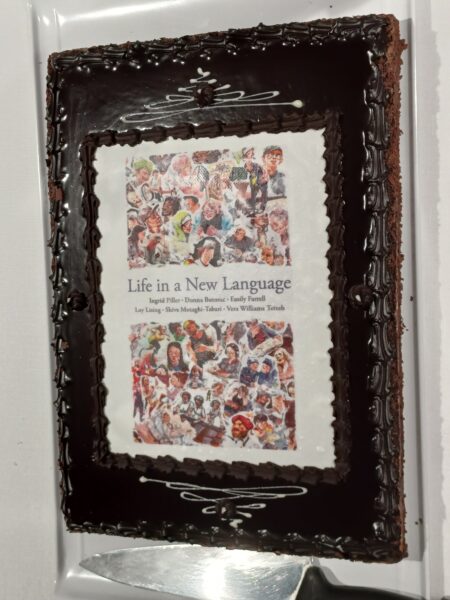

We celebrated with a big launch party last Friday and there are some photos for absent friends to enjoy on the book page. There you can also find additional resources such as a blog post on the OUP website about data-sharing as community building or this one on the Australian Academy of the Humanities site about being treated as a migrant in Australia. Feel free to bookmark the page as we hope to keep track there of the life of the book.

Don’t forget if you order the book directly from Oxford University Press, the discount code is AAFLYG6.

If you are teaching a course related to language and migration, consider adopting the book. It includes a “How to use this book in teaching” section, which will make it easy to adopt. Contact Oxford University Press for an inspection copy. Book review editors can also request a review copy through the same link.

Transcript of Part 6 of the Life in a New Language podcast series (by Brynn Quick, added 05/08/2024)

Brynn:

Welcome to the Language on the Move Podcast, a channel on the New Books Network. My name is Brynn Quick and I’m a PhD candidate in linguistics at Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia. Today’s episode is part of a series devoted to life in a new language.

Life in a New Language is a new book just out from Oxford University Press. It’s co-authored by Ingrid Piller, Donna Butorac, Emily Farrell, Loy Lising, Shiva Motaghi Tabari and Vera Williams Tetteh. In this series, I’ll chat to each of the co-authors about their perspectives on writing the book.

Life in a New Language examines the language learning and settlement experiences of 130 migrants to Australia from 34 different countries in Africa, Asia, Europe and Latin America over a period of 20 years. Reusing data shared from six separate sociolinguistic ethnographies, the book illuminates participants’ lived experiences of learning and communicating in a new language, finding work and doing family. Additionally, participants’ experiences with racism and identity-making in a new context are explored.

The research uncovers significant hardship, but also migrants’ courage and resilience. The book has implications for language service provision, migration policy, open science, and social justice movements. My guest today is Dr. Emily Farrell.

Emily earned her PhD from Macquarie University in 2008 with a thesis entitled Negotiating Identity, Discourses of Migration and Belonging. She completed a DAAD-supported postdoctoral fellowship in 2010, focused on language and the international artist community in Berlin. She began her career in publishing as the acquisitions editor for applied linguistics and sociolinguistics at DeGreuter, and has since worked in sales, business development, and in the commercial side of publishing for the MIT Press, and now as the global commercial director for open research at Taylor & Francis.

She was an early board member at UnLocal, a legal services and educational outreach organization that serves undocumented migrants in the New York City area, and also served on the board of the foundation for the Yonkers Public Library. At Taylor & Francis, she focuses on increasing access to research through support for both open access agreements and open research practices, including data sharing, as well as support for humanities and social sciences in particular.

Welcome to the show, Emily. It’s wonderful to have you with us today.

Dr. Farrell: Thanks so much, Brynn.

Brynn: To get us started, can you tell us a bit about yourself, how you got into linguistics, and how you and your co-authors got the idea for the book, Life in a New Language?

Dr. Farrell: It’s great to think back along the trajectory and also to think about the six of us, and what brought us all together in the end to combine some of our research projects, and to work together, and the work we’ve done together over a lot of years.

For me personally, I, now long ago, left Australia for the US study, and when I came back to Australia after a few years in the US, after an undergraduate degree, I was more in English Literature and Music. I had the experience of living elsewhere, in some ways growing into a young adult in a different country, even though America, obviously the US, is an English speaking nation predominantly, that experience of going there at age 18, growing there, seeing myself in a different light, and in ways creating a new space for myself and identity, and then coming home and sort of drawing all those pieces together.

I’d become interested in language through that, and particularly that idea of how do you kind of create belonging for yourself in a new place as you grow across your lifespan. And when I got back to Australia, I actually started a master’s degree at Sydney with Ingrid Piller. She had not been at Sydney for a long time at that point.

I was teaching courses with a linguistic grounding in cross-cultural communication, and I was completely hooked once I started because it drew together all these things that had sort of been percolating, you know, the idea of identity creation, how language fits into that picture, how people assess each other and the biases people have based on the way that people sound, whether that accent’s within a, you know, whether it’s a Southern US accent versus a, you know, received pronunciation in the US, and all that kind of groundwork in closely linguistics. I think once you start to read all of that literature, really, I found it so captivating. And it sort of started to answer lots of questions for me about all these things that you get a hunch about, but it’s also, in what’s a way, so implicit, right?

Because it’s language, and you sort of take it for granted. And so being able to dive into that sociolinguistics and applied linguistics literature and starting to understand all that from a new perspective was just so captivating. And so, from there, it was at the time that Ingrid had just secured an ARC grant to look at people that had migrated to Australia and become highly proficient in English.

And so, I started on a research assistant with Ingrid and started my PhD on a related topic to that. So particularly looking at the cohort of highly proficient speakers and how they were navigating this sense of belonging and identity and how that connected to language.

Brynn: It’s so true, I think, that nothing radicalises us more than when we have to kind of leave what we know in our home country and, like you said, even if we go to another country where technically we speak the same language, all of a sudden you realise, oh, wait a minute, there is so much more to establishing a home for myself in this new place and to establishing this sense of belonging than just being able to speak the language.

You’re an Australian living in the US., I’m an American living in Australia, and I think we probably have both experienced that, and even before we started this recording, we were talking about how interesting it is that, you know, technically, yeah, we speak the same language, but we’ve both experienced having those cultural moments where just because we can technically understand each other, that doesn’t mean that it’s easy, and I love that that kind of was this through line for you because then when you were looking at this research where you were a research assistant, you were looking at these people who had high levels of proficiency in English.

So, technically, they can speak the language here, and yet there was still this sense of, but I’m not able to establish this sense of belonging maybe in the same way as someone who sounds like someone from this area.

Dr. Farrell: Yeah, and I think that, you know, you do have all this privileging, obviously, depending on the sort of accent you have and obviously how audible you are, how visible you are as other in a place, and we were talking about this a little bit earlier as well, just seeing that again with my son, who’s six, and has a very strong American accent, bringing him back to Australia where he has an Australian passport and an American passport, and, you know, I am audibly Australian or, well, not all Americans, can I identify the accent to be honest?

Brynn: I’m sure many think you are British, yes.\

Dr. Farrell: That’s fine, I forgive them. But it’s also another point that was of interest to me in my research, which is our national boundaries and citizenship also sort of create these categories where people do and don’t fit. So just because you have a passport, does that make you feel like you’re able to sort of create an identity of belonging or how do you find these sort of in-between spaces?

So, you know, so often the people in my research were sort of, they talked quite a lot about accentedness, how they had been in Australia for, you know, 30 years were master’s degree holders, were incredibly accomplished, people who could sort of suddenly have this experience of being other just because someone would say to them, Oh, where do you come from? Because they would hear their accent. And it’s tricky because, you know, there is that weird power in such a banal question.

And you know, sometimes that felt really frustrating for people. But sometimes that also was, you know, I got to hear some of these amazing stories from people who were then able to kind of mobilise a much more powerful in-betweenness or transnational feeling, where they sort of felt, well, yes, you can hear I come from somewhere else, and I do come from somewhere else, but I also come from here. And that it doesn’t necessarily have to be either or in that way.

And that there is a lot more, you sort of can create a bigger space for yourself. But it’s sort of not always quite so easy, because there is kind of that, again, it’s that banal sort of everyday othering that might not seem so consequential for someone else because they’re asking a question that’s just, that seems simple. But for someone that’s asked that, oh, where do you come from?

Or, you know, what accent do I hear? You know, hearing that over and over again can feel really frustrating in your own sort of personal project of, you know, making a life for yourself somewhere else.

Brynn: And I’m sure both you and I have heard that question. I literally had that question asked of me last night. I had an Australian man say to me, and what accent do I detect?

And I wanted to say to him, I hear yours. I hear your Australian accent, you know?

Dr. Farrell: Yeah.

Brynn: You’ve gotten that in America too.

Dr. Farrell: For sure. And I do think you get that much more in English-dominant monolingual environments where people aren’t used to switching between languages. There’s just certain, you know, assumptions about what it is to sound a certain way, what counts as an accent.

That’s quite fascinating. I mean, it also, part of that kind of international, interesting kind of international basis is what drew me to the post-doctoral work that I did in Berlin, because you have this fascinating environment where, at least when I was there in 2009, for three years, it was still a pretty affordable place to live. And it was really, by that stage, you know, the wall had come down quite some time beforehand, I suppose, you know, 20 years before, but there was still this kind of sense of this emerging city and a real kind of very vibrant artistic community that was starting to sort of, people were talking about, like, people in New York, everybody kind of knows about New York or Berlin and sort of another hub for artists.

And so, there’s sort of a real international community there. But English still, there’s a real dominance of English in that environment. And a lot of people that have kind of moved, they’re not thinking about moving to Germany, but thinking about moving to this kind of international art city.

And just the way that language circulates and how people learn languages and which languages they’re speaking, which bits of what in different ways, in different spaces was so interesting to me, because a lot of the ways that people there were doing this sort of identity work and belonging work was much more about being able to be in a space where you could define yourself as an artist, whereas in New York, it’s really hard to balance paying the rent and also work on your artistic practice.

So these sorts of, all of that sort of the way, you know, all these pieces to me connect to this idea of you’re doing all this work of how do you find a job, how do you raise a family, but also how do you do this sort of your own work to feel like this is where you belong and, you know, how do you find your people and how do you make that space for yourself?

Brynn: Yeah, and that is a very central part of the research that you brought into this book, Life in a New Language. Can you tell us a little bit about your participants in the research that you did? You said that they had high levels of English proficiency, which is a little bit different from some of the other participants that we’ve discussed in this series that some of the other authors worked with.

What was that like? What did you see in your participants in having that high level of English, but maybe still seeking to build belonging and build a home?

Dr. Farrell: Yeah, so the people that I spoke with during my research were all, they’d all migrated to Australia as adults. They had a mix of different amounts of English education before arriving in Australia. Most of them had migrated from Europe or South America and were already reasonably highly educated and then a good number of them got higher degrees once they got to Australia.

They were going through that process of learning English but were, and a good number of them were already reasonably proficient once they arrived in Australia. And it was a mix of reasons for migrating, a good number being sort of economic migration or a lot of actually there were a couple that had moved for a partner, they’d met an Australian and moved to see where that would go. And a lot of the people that had been in Australia the longest, I think, had already been here 30 years, I think it was the maximum.

Some had only been in Australia for a few years. But all of them were sort of in that process of setting their lives up or raising their families and were much more in that space of sort of how is it that you continue to kind of find community and belonging in a new language. And also how, you know, where you find ways to use the languages that you arrived with.

So, one of my favourite set of participants or a couple, I really felt very privileged speaking to this couple who had both, they had these fantastic stories of the way that they had met and the romantic story and their language use in Australia and their community building here, where they had both left Poland separately. I think, you know, we did in the space of a year or two of each other. And the man had left first and they’d both ended up in Denmark.

And I don’t think either of them had had much Danish before leaving Poland. She had moved with a daughter, very young daughter. They met because he was visiting a friend that was also in one of these living spaces.

They’d put people up, like early migrant housing. And he tells this fabulous, they sort of tell this story together, where he talks about how he sees her for the first time and he immediately thinks that she’s this incredible woman. And she, at the same time, is sort of telling their meeting story, sort of saying, oh, I thought he was crazy.

He was like, this guy just seen me and he’s trying to give me his phone number. And I was like, what’s this about? Some crazy man’s shown up and he’s just giving me his phone number.

He doesn’t even know. He probably does this for every girl. But then, you know, they sort of go on and then they went on a date and then, you know, end up married with another daughter.

And then ultimately, you know, many years later, they migrated to Australia with both daughters and raised a family here. And the way that they sort of tell that story with lots of humour, sort of teasing each other, like much love, but just kind of how language can weave through that narrative. And that once they got to Australia, you know, they have the elder daughter who is most comfortable in Danish but speaks highly proficient Polish and now English.

The younger daughter who grew up mostly in Danish. So, it’s sort of the way that the family then talks to each other. You know, you have the parents still speak to each other in Polish.

You know, the elder daughter often speaks in Danish. You know, so they have all these different languages that they’re using sort of over the dinner table, you know, in the ways that they kind of craft what it is to be a family in Australia, and then how they’re sort of finding their own seat and sort of continuing to live out their own practices that fit their family in Australia. And it’s just really amazing to hear just how complex, but also how people are able to sort of craft these spaces for themselves and to find ways to use and continue their own language repertoire when they’re here.

Brynn: And that’s something that we’ve heard from some of the other authors, too, is about this negotiation of family over the dinner table. You know, like these languages that get used in just the ways that the family as a unit interacts with each other. And it can be really broad with meaning, the different choices that are made for the languages.

And that’s just in your own house. That’s not even thinking about then what did the parents do when they leave the house to go to work? You know, what language choices are they making then?

Or what do the kids then do now that they’re in Australia and presumably going to an Australian school? What are those language choices? So, it’s really interesting that it can be as small as that nuclear family.

And then you think about the way that language choices branch out from there.

Dr. Farrell: Yeah, absolutely. What’s so beneficial about, I mean, what we’ve done with this book in drawing together these six different studies and covering a large period of time, 20 years, and also a large group of people, 130 people, we get all that really beautiful, sort of rich granularity of the stories you hear from people that do defy the sorts of stereotypes and assumptions that you have about what people actually do in their lives because so often, you know, even those of us who’ve spent a lot of time, you know, thinking critically and studying this specifically, you know, you’re taking in so much media, politics. It’s easy, I think, to sort of get detached from what it is to understand the real detail of lived experience.

And then it’s also incredibly challenging, I think, again, even for those of us who have our heads in this sort of work, to think about how you take that detail and try to bring it out to that more sort of policy level, to that more, the public space where these sorts of issues are politicised and flattened out and simplified in such ways that are really quite detrimental to the actual lives of people. And I think that when Ingrid was discussing the idea of drawing this study together into one book, what was so appealing to me was the fact that so often, when you think about ethnographic work, it is about that detail and that’s the importance of it, right? Is that you are able to sort of take a context for what it is, really listen to the people, the community that you’re working with and in.

But then I think all of us who have done this sort of work get to that point where it’s difficult to know how to try to have a greater impact. And I think that when you think about the real sort of applied part of applied linguistics, I think all of us want to see more of an influence on the broader discourse around language and migration or other sort of language use topics. And I think it’s really quite difficult to see how you make that impact and how you try to connect what you’re doing in that sort of granular way to the broader sort of ways of speaking across society.

And I think, you know, you sort of have things like census data which really just doesn’t give you that qualitative or detailed view. And in bringing together these six different studies, we have the hope that we make a bit of a step towards the ability to be able to say, look, this isn’t just one person’s or this small community’s experience. We can look across these different communities of people or different individual migrant experiences and draw from them together from this group of 130 people, very common threads that show us, I think, some direction for how we could shape policy, how we could shape education, how we could shape even individual interaction with people when you don’t ask where somebody comes from.

You know, there are certain things you can start to think about your own ways of approaching someone as a human in interaction that I think can have both on a small scale and then on a societal level a really big impact for positive change.

Brynn: And that’s why I think Life in a New Language is just such a groundbreaking book because as I’ve said in previous episodes, you do not have to be a linguist to read this book, to understand this book, to get a lot of meaning out of this book because it does show this really human experience that we all have when we are the new kid in a place, you know. And like we said earlier in this episode, it doesn’t even matter if you already speak the language of the place that you’re going to or in the case of your participants, you have a high level of proficiency. There is still so much that goes into being a migrant, and there’s still so much that you have to build into your life as a migrant that doesn’t necessarily come easily.

And that’s why I think bringing these six studies together, just like you said, so well, shows what we can do as individuals on an individual level is just have that human empathy for each other and then also can say, well, hey, look, we’re noticing these trends in finding work, in getting an education for kids. We’re seeing this through line in how we do family and how we negotiate language and family. And I think, like you said, that’s something that could be taken to that policy level so easily.

So that’s why I think the book is so fantastic. And speaking of that coming together with all of those six stories, I would love to hear about your experience in co-authoring with five other people and bringing those things together. And what I think is so interesting about your particular experience is that you were doing all of this from the other side of the world.

You were living in New York. I think it was four of the authors were living in New South Wales and then one was living on the other side of Australia. But you were the furthest away and you had a little baby at the time.

So, what was all of that like for you?

Dr. Farrell: Yeah, so I was the spanner in the time zone works. For me, I had moved into publishing quite a number of years beforehand. So, we, I think, started discussing this book in 2018 when my son was six months old, I think, and around then, six, eight months old.

And so, I’d already been working in publishing for around eight, seven or eight years by then. It was really quite a joyous experience to be able to rejoin and revisit this research that I hadn’t really been working, I hadn’t worked with for quite a long time and to feel like there was still so much in there to draw out and draw together and, you know, and have the opportunity to work with five incredible other women who have done such brilliant work and to sort of see how we could fit our different projects together. Obviously, you know, we had Ingrid as the consistent, you know, the supervisor across all these projects, which I think gave us a huge benefit in already having a certain shared framework and viewpoint.

But even then, I mean, there was still so much to do for all of us to sort of go back to the research we’ve done, you know, some more recent and some older, and sort of go back right from the beginning, back to the transcripts, really read back through, you know, and I haven’t done that in quite a long time, and to really kind of view it again from this perspective of how are we drawing these together, what are the shared, you know, themes that we can bring out, how can we sort of make this most powerful and also most accessible, I would say, so to a broader readership. And, you know, I mean, certainly with six people, everybody works at a different pace, everybody’s juggling different commitments. No, I think that were it to have just been a single author, the book probably would have moved at a different pace, but we also managed to do it through a number of years of a pandemic and, you know, where I wasn’t able to come home, I hadn’t been able to get back to Australia for about three years.

So, you know, there was certainly not the same as sort of working on something on your own, but I think the benefits that you gain from bringing these projects together and the things that you can learn from, you know, the viewpoint of different co-authors, it’s been an incredible experience, at least from my perspective. I feel very lucky to have been part of it. And I think that what we have at the other end of these years of drawing it together is, you know, something greater than the separate parts, which is really, truly fabulous.

Brynn: And I think what’s very cool is that because your son was, you said, six, eight months old, at the time that you started, he’s now six years old, right? So, we have like this child that grew with the book, which is so cool. And also, you know, many of us in the research group that we have, Language on the Move, many of us are mums, and many of us are doing the juggle of the academic work and the raising of the family and trying to figure all of that out.

What was that like for you, especially being in that other time zone and juggling this new motherhood as well?

Dr. Farrell: You know, I think what’s so eye-opening about it is that you just sort of are able to, there’s obviously a lot to juggle, but at the same time, I think it helps you prioritize, it helps you sort of see what’s important. And for me, where I was often kind of working late into the evening and you have to turn the laptop off or at least shut it, shut it down, close the lid, you have to go and help with your nod, do your story time. You know, I think that that’s, it’s a really important kind of chance to look at what matters and also see that you can get a tremendous amount done, you just have to work out the ways to get the schedule right, I suppose.

And I mean, that’s all, again, saying that from a point where I have a very supportive partner and also that working with five other incredible authors who are also juggling their lives and incredible, the huge amount of work that everybody has on their plate, both family commitments and professionally, I think it’s a real, it’s a really good way to see how much you, it’s not a vulnerability to rely on a group and to have a network of support and that it’s so, so important to have that. And I think being able to see that strength in others and look at what people are managing and sort of how everybody supports each other and cheers everyone on. You know, I think it’s been, for me, having seen, I mean, I think we all see this in different ways, the sort of very competitive environment of academia.

I mean, I stepped outside of it, you know, working in publishing, but I’m certainly still very adjacent to it, very much adjacent to it. So, I see how difficult the job market is and, you know, I experienced that to some degree in sort of initially trying to apply for academic jobs, and that hasn’t gotten me better since I left academia. And I think that making sure that you’re able to find a really supportive network, just for mental health, honestly, and also for those moments where you lose belief in your own work or you get a job rejection or you maybe lose direction a little bit to have a supportive group that can remind you that, you know, what you can do and what you can achieve, I think can’t overstate the importance of that.

Brynn: And that really comes through in the book, in reading the book and knowing that the six of you did this together. It’s one of my favourite things about the book is that collaboration and that camaraderie. And as I’ve said to some of the other authors, it sets a great example for the rest of us in the Language on the Move research group who are kind of just starting this process because we have learned how to support each other in this academic field that can be really hard and it can be emotionally hard to get rejected, you know, in papers or publications or things like that.

But I love being able to work with each other. And I think that makes our research better when we’re able to collaborate like this as well. And you mentioned that you stepped outside of academia and went into publishing.

I would be really interested to hear what that’s like and sort of what you do now and what you’re up to these days and sort of the decision that led you into publishing and what it’s like. Because those of us in the beginning of this process, we’re on the other side. We’re trying to get our papers published.

We don’t know what it’s like to work on your side. So, I’d love to hear about it.

Dr. Farrell: Yeah, I mean, that’s one of many fascinating parts that I still remember how much fear and worry I had about publishing as a PhD student. And then, you know, you get a very different perspective of it when you get on to the other side when you work for a publisher. And, you know, I used to do more frequently when I was an editor, I would do how to turn your dissertation into a book workshop and things like that and constantly sort of trying to encourage students or early career researchers.

So really, when you’re at a conference making an effort to talk to publishers, go up and talk to editors, hear what they’re looking for, ask them about what they expect in a book proposal or, you know, what their journals are like and get as much information as you can. Don’t be afraid. I mean, they’re there to try to, especially books acquisitions editors, you know, they’re looking for new projects.

They want to work with people. And so, you know, the more you can kind of mine out of people that work for publishers, the better. I think there’s a lot to learn there, especially because you do find at a lot of academic pressures that you have a lot of former PhDs or people with PhDs working in their field, acquiring books in their field.

So, yeah, I mean, I was drawn into publishing because I finished in 2008, 2009, right, as the job market crashed. And I had sort of been on the fence about a standard academic career. I adore teaching, but I wasn’t entirely sure that I was cut out for a really focused academic career in the ways that I sort of– when I looked around at the people that were really excelling and were really dedicated to their academic careers, I wasn’t entirely sure that I was sort of willing to give up.

It felt like to me when I looked at it, and I know that this isn’t the case for everybody, but I sort of looked and it felt like there were things I would have had to give up. I wasn’t willing to give up. The other thing was, frankly, from a personal point of view, and I know that people think about this, but I don’t know that people sort of voice it very often.

I had a partner who could only really work in a few cities, frankly. He works in the art world. I didn’t want to move to the middle of nowhere just for a job.

And I didn’t want to drag a partner who wouldn’t have any job prospects to a small town somewhere. And I didn’t feel that I was really competitive enough to get a job in a big city where so many people would be competing for jobs. And so I’d considered that maybe publishing might be a path.

And as luck would have it, when I was living in Berlin, I saw this job ad for an acquisition editor in books for applied linguistics and sociolinguistics. And I sort of felt, well, if that’s not my job, I don’t know what is. And was lucky enough to get it and that sort of started my career in publishing.

The other thing that I think is worth keeping in mind, and I have spoken to people that are sort of looking for perhaps non-academic careers after their PhD, is that a lot of people look only at editorial work in publishing. I started out as an editor and it was incredibly rewarding. It ended up that I got the chance to sort of stay connected to the field.

I got to go to a lot of conferences that I couldn’t afford to go to as a student. I got to meet lots of amazing people and speak to academics who I was sort of in awe of, because they’re, you know, knowing their research. But ultimately, I started to get more interested in kind of the bigger picture of publishing and, you know, the scholarly communication ecosystem and knowledge sharing and distribution.

What does that mean? How does it work? And at the core of that too is how does the business side of it work?

I mean, I think when you’re inside the sort of academic space, you can seem a bit, I don’t know, less appealing to sort of think about those sort of more commercial aspects. But I started to get drawn in trying to understand those parts and have moved from editorial into the commercial side and now working particularly with sort of open access business models. And it’s been a really interesting journey to sort of be able to take all of that academic knowledge and the experience in the research side and kind of consider, well, what does that mean for ultimately a sustainable knowledge distribution sharing landscape?

And how do we do as much good in that as we can? How do we make sure information scholarship is accessible to the broadest amount and broadest group of people? You know, what does that mean and how do you do it and all of that?

What does it mean infrastructurally? What does it mean, you know, what are all the gory details of that has become, you know, very interesting? So, I think, you know, I guess all of that to say, you know, it’s worth keeping an open mind and kind of looking across publishing.

That’s something that should be just outside of an academic career. And, you know, I’m always happy to talk to people about it, especially early career or students, early career researchers and students that are considering other pathways.

Brynn: Well, and I’m glad to know that people like you are out there doing that work because I think wanting to bring the research that we do and the knowledge that we in the academic world have to the broader public. That’s something that I feel really passionate about. I’m always advocating putting things into language that lay people can understand.

And I think that that’s really, really important. So, I’m really glad that that’s something that you’re doing.

Dr. Farrell: What was so lovely about ultimately sort of getting to the conclusion of the book was that, no, we knew it from the beginning, but once we’d sort of written the book and we were kind of concluding and thinking about what it meant to have drawn all these studies together, we sort of ended up coming back to this notion of data sharing. And that’s become such a big topic in open access and sort of increasing open research practices. And it’s been such a big topic in hard sciences, where there’s been the sort of crisis of reproducibility and replicability in some of the more quantitative social sciences.

You know, there’s been a lot of discussion about that sort of thing and issues around research fraud and research transparency. It’s really only more recently where there’s been more of a discussion about, well, what does that mean for the humanities and social, more qualitative social scientists? And should we be sharing data?

How on earth can we share data? Do researchers in humanities even call what they have data? Should we be sort of forcing these frameworks on researchers from the outside, either as publishers or, you know, the sorts of mandates from funders to share data?

Obviously, you have funders like the Gates Foundation that have a data sharing policy, and others, you know, more and more of these mandates for sharing research. But, you know, have we done enough of the work in thinking about what that means for ethnographers in particular? Because especially if you haven’t built sharing into what you’ve done from the beginning, there are so many ways that it can feel very complex, not just personally from the point of view of, oh, I don’t know that I feel comfortable sharing all these, you know, field notes and so forth with other people, but also that they’re sort of not written to be read by anyone else, but also that there’s just so much context that’s not there just in the transcript or even in your field notes.

And so, part of what we ended up being able to explore a little bit is that we see the benefit of drawing these studies together, but we also saw the challenge of, you know, how on earth you do that. So, you know, how do you provide the context? How do you make sure that your notes and your transcriptions are read in the right ways and not taken without all of that extra detail?

So, you know, I think in some ways it’s something of a beginning of a journey to think about what data sharing truly means for ethnography and how we can really best draw on the huge benefits, I think, that we all saw this sharing, but also do it with the right amount of caution in kind of considering how we connect these pieces together and what it would mean for somebody else coming from the outside to use it. I mean, I think that’s also come up more and more in the last year with the explosion of large language models and AI and knowing that if we’re making this data available publicly, what does it mean if a ChatGPT, et cetera, is using that data to feed modelling without any broader context? How do we consider what that means and how we’re feeding that?

So I think it’s very topical and I think at least for me being so involved in open research from the publisher side of working very closely with libraries and some funders, considering what it means to actually be part of the research side of it, digging in and understanding in more detail what are the benefits but also the real challenges here and I think there’s a lot more thinking to be done there. So, I’m really hoping that out of this book, you know, we can continue to think about and work on ways that we can buffer and care for our data in the right way and care for the people that are that data when we’re talking about ethnographic work. So yeah, for me, I really hope in my professional life to continue to expand on what that means, even in things like how we talk about our own open data sharing policies for humanities and social sciences at Taylor and Francis. So, there’s so much more that can come out of this.

Brynn: And you’re right, it’s such a huge topic right now – data sharing, doing collaborative work, making sure that your data is available for reuse and reproducibility. And that’s what I think Life in a New Language does so well and is such a good ground breaker for that. Thank you for giving us that food for thought.

And on that note, thank you for being here today. We really appreciate it.

Dr. Farrell: Likewise, thanks Brynn. Thanks for all the fabulous questions and great conversation and yeah, looking forward to talking more.

Brynn: And thank you to everyone for listening. If you enjoyed the show, please subscribe to our channel, leave a five-star review on your podcast app of choice, and recommend the Language on the Move Podcast and our partner, the New Books Network to your students, colleagues and friends. Until next time!

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a

Congratulations once again to you all in this incredible achievement! I was so sad to miss the celebrations but will continue to celebrate this from afar!

Thanks, Laura, maybe we’ll get to UNE on the book tour 🙂