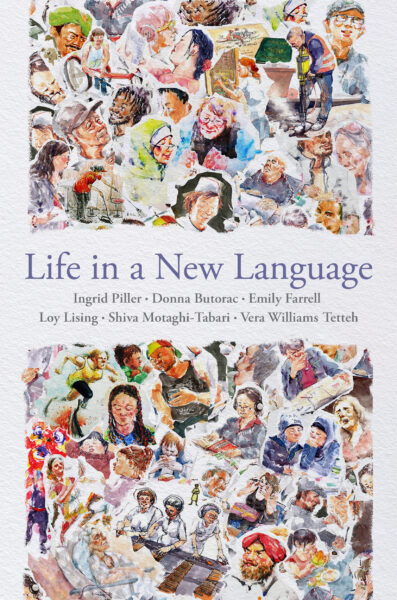

This episode of the Language on the Move Podcast is Part 1 of our new series devoted to Life in a New Language. Life in a New Language is a new book just out from Oxford University Press. It is a project of Language on the Move scholarly sisterhood and has been co-authored by Ingrid Piller, Donna Butorac, Emily Farrell, Loy Lising, Shiva Motaghi Tabari, and Vera Williams Tetteh.

International migration is at an all-time high as ever more people move across national borders for work or study, in search of refuge or adventure. Regardless of their motivations and whether they intend their moves to be temporary or permanent, all transnational migrants face the challenge of re-building their lives in a different cultural and linguistic context, far away from family and friends, and the everyday routines of their previous lives. Established populations in destination countries may treat migrants with benign neglect at best and outright hostility at worst.

How then do migrants make a new life?

To answer that question, Life in a New Language examines the language learning and settlement experiences of 130 migrants to Australia from 34 different countries in Africa, Asia, Europe, and Latin America over a period of 20 years. Reusing data shared from six separate sociolinguistic ethnographies, the book illuminates participants’ lived experience of learning and communicating in a new language, finding work, and doing family. Additionally, participants’ experiences with racism and identity making in a new context are explored. The research uncovers significant hardship but also migrants’ courage and resilience. The book has implications for language service provision, migration policy, open science, and social justice movements.

In this series, Brynn Quick chats with each of the co-authors about their personal insights and research contributions to the book. Today, Brynn chats with Dr. Donna Butorac, one of the book’s six co-authors, with a focus on how identities change in migration.

Use promo code AAFLYG6 for a discount when you purchase from Oxford University Press.

Advance praise

“This volume breaks new ground by focusing on Doings: a group of diverse researchers collaboratively doing close listening and looking over 20 years, as adult immigrants to Australia engage in doing life, things, words, family, and work in a new language. The result is not only new understandings of the participants’ self-making, but also the making of a new research trajectory that focuses not simply on the learning of a language, but on humanity doing life in language.” (Ofelia García, The Graduate Center, City University of New York)

“This is a moving book that represents the voices of migrants on their challenges and successes across different kinds of boundaries. It embodies impersonal structural and geopolitical pressures as negotiated in the dreams and aspirations of migrants. The authors share findings from decades-long separate research projects to develop richer insights, as a model for data sharing and ethical research.” (Suresh Canagarajah, Pennsylvania State University)

Transcript (by Brynn Quick; added 13/06/2024)

Brynn:

Welcome to the Language on the Move podcast, a channel on the New Books Network! My name is Brynn Quick, and I’m a PhD candidate in Linguistics at Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia.

Today’s episode is part of a series devoted to Life in a New Language.

Life in a New Language is a new book just out from Oxford University Press. It’s co-authored by Ingrid Piller, Donna Butorac, Emily Farrell, Loy Lising, Shiva Motaghi Tabari, and Vera Williams Tetteh. In this series, I’ll chat to each of the co-authors about their personal research contributions to the book.

Life in a New Language examines the language learning and settlement experiences of 130 migrants to Australia from 34 different countries in Africa, Asia, Europe, and Latin America over a period of 20 years. Reusing data shared from six separate sociolinguistic ethnographies, the book illuminates participants’ lived experience of learning and communicating in a new language, finding work, and doing family. Additionally, participants’ experiences with racism and identity making in a new context are explored. The research uncovers significant hardship but also migrants’ courage and resilience. The book has implications for language service provision, migration policy, open science, and social justice movements.

My guest today is Dr. Donna Butorac. Donna is Senior Lecturer and Coordinator of Anthropology and Sociology at Curtin University in Australia. She has a background in applied and sociolinguistics and has researched and published in the areas of language learning and migration, and teachers’ professional development.

Welcome to the show, Donna! We’re really excited to talk to you today.

Dr. Butorac: “Hi, Brynn. It’s nice to be here.

Brynn: To get us started, can you tell us a bit about yourself and how you and your co-authors got the idea for Life in a New Language?

Dr. Butorac: Sure. So right now, I teach at a university, but for a lot of years I taught English to adult migrants in the Australian Settlement English Program. And it was actually while I was there that I completed my PhD in applied linguistics.

I had done an undergrad degree in anthropology and linguistics, and then I worked and traveled for a lot of years. And then I did a post-grad diploma in TESOL in Canada, and then later did a master’s in applied linguistics at Macquarie. And so, I had taught a lot of international students, like in Sydney and Vancouver and in Perth as well.

But it was while I was teaching in the Settlement English Program in Perth, I began to wonder while I was working in Perth in the Settlement English Program about what it was like for the students who were sitting in front of me. I’d be standing in front of the classroom looking at them and going, what’s it like to be them right now? What’s it like to be, and they were mostly women a lot of the time, what’s it like to be them developing a voice in English in this place, in this time?

And so that kind of thinking shaped the PhD that I subsequently undertook, and I was actually really fortunate to have Ingrid Piller and Kimie Takahashi as my supervisors for most of that degree. So, I completed that in 2011 and I pretty soon went into full-time university work, but initially for three years I was working in a leadership role in learning and teaching, and then I went straight into anthropology and sociology in 2015. And because I was involved in work that wasn’t closely related to what I’d done my PhD, and because I was trying to focus on being a mum as well, to be honest, I didn’t do much publishing on my research.

And then I think it was probably in about 2018 Ingrid approached me and four other women to ask if we’d be interested in writing a publication that was based on our combined research projects. And because they’d all been on language learning and post-migration settlement in Australia, and we were all really keen, I was certainly keen, I know the other women were too. So, we met at Macquarie in 2019, I think, to workshop the ideas and to plan the book.

Brynn: I’m sure nothing then happened in 2020, did it (laughs)?

Dr. Butorac: Yeah, of course. Yeah, it kind of went slow. I mean, we were still in touch, you know, obviously, over Zoom and so on.

But I can’t remember, yeah, it’s a bit of a blur, actually, the whole COVID period. It’s like, it’s like life stopped for a while. And I think, was that before COVID or after COVID?

You know, you kind of have these phases in your life. So, yes, it was a slow project to get going. But we’ve gradually kind of pulled it all together over the last few years.

Brynn: You really have. And you just said so many things that speak directly to me. Being a mum who is trying to do academic work. I also am a mum trying to get my Ph.D.

And I also feel like so many of us that go into the teaching English space, we also maybe kind of also want to major in anthropology. I know I went through a phase where I actually was an anthropology minor in undergrad for a while. And I really think that those two areas go well together, because like you said, we do as teachers, especially of adults, kind of get up there in front of the class and you do, you look out at all of these people that you’re teaching and you think, where did you come from? What is your story?

Dr. Butorac: What’s your story? What’s it like to be you. Yeah, I haven’t thought about it like that, but it’s true.

You always take that because my undergrad was anthropology. And even though I did, like, for my honors, I challenged myself to do what I was probably least naturally leading towards, which was the really pointy headed stuff. And I did it on the adverb, you know.

But what I was really interested in was people who speak and people. And so, I feel like I’ve come full circle and that sort of culminated in the PhD, which I think is really sociology of language rather than linguistics. And so now teaching anthropology and sociology, I feel very much at home in these disciplines.

I feel like I’ve had these different elements all come together in actually being a teacher in this field.

Brynn: What an awesome combination. I love that. And I love that idea of the sociology of language rather than what I think a lot of people think of when they think of linguistics is that we’re all grammar pedants, you know, and that’s not it. A lot of us do this more sociolinguistic work.

And speaking of that work, Life in a New Language, the book that we’re talking about today, is all about the reuse of ethnographic data, which is really interesting and it’s quite novel for this book. Can you tell us about the original research project that your contribution to this book is based on?

Dr. Butorac: Sure. So, what I did was I explored language learning and identity, because I was really interested in what’s it like to be them and how do they see themselves. And so, I worked with nine women who had recently migrated to Australia.

And they were all, when they started, they were all studying in the Migrant Settlement English program. So, it was a longitudinal ethnography and it followed those women over a 22 month period. And it was based on in-depth personal interviews.

And I did those at the beginning. I planned to do them at the beginning, in the end, I ended up doing another set in the middle, but I also did group discussions. So, the group discussions were on a single broad topic.

Being a woman was one of them. Society, what it was like for them being in the world, in Australia. That’s where things around their experience of racism or their mixing with other people came in.

Also learning what it was like to be learning and their experiences with that. Their sense of who they were, their self. And then relationships was another one.

And then I kind of threw open the topics for them to include others as well. I also got them to do an essay writing task. I wanted to know what their plans and aspirations were for the future, for their life in Australia.

And I got them to write that at the beginning and then at the end, because I was interested in, okay, what’s going to be the impact of learning English on them as women, how they see themselves and how they understand their desires for the future. Would that change as in theory, as they got better with learning English and had more confidence in their voice and their use of English? Because yes, so I wanted to see how my broad goal was, how does learning English in Australia impact their sense of self and their feelings about who they could be as a woman?

Brynn: I’m so interested in that because I also remember a few years ago when I was teaching, I think maybe in the same program or at least a similar program to adults. I would see so many of these women and we had this thing in common about we have kids at school, we need to leave right at 2:45, we need to go pick them up from school. To me, that is such an additional element to language learning, is having to parent while you’re doing that and all of the hopes and aspirations that go into your own language learning, but then also what that means for your children.

But also, your brain is exhausted at the end of a language learning day and you’ve still got to go home and parent.

Dr. Butorac: Yeah, it’s true. And in fact, one of the women in the project, she had a really interesting experience with that because she and her husband had migrated from Brazil to Japan and they lived there for five years because he had a job there and he spoke Japanese because he was Japanese Brazilian. He was from that community in Brazil.

She was from the Chinese Brazilian community and their daughter. So, they all spoke Portuguese together, but living in Japan during that time, she had a very young daughter. The daughter really bonded with Japan, everything Japanese.

And so, she started speaking Japanese. Her mum never really learned it and the daughter stopped speaking Portuguese. By the time they came to Australia, she said, oh, it’s really interesting. My daughter refuses to learn English. She doesn’t want to be here. She wants to be back in Japan.

And so, the daughter and father could speak Japanese together, but the daughter couldn’t speak to the mum very much. She would talk to her and she would understand bits or she would say, oh wait till Papa comes home and get him to mediate. But she was the main caregiver because he was working full time.

So, these sort of things happened through migration and through people identifying or having aspirations towards one language or one culture, but it’s out of sync with where their parent is at, perhaps. In this case, it was out of sync with where the mum was at. She was so invested in being in Australia because she thought this would be a better life for all of them.

Brynn: Did the daughter ever learn English?

Dr. Butorac: No, she did eventually. At first, she refused and so her mom was great. She put her into the Japanese school, there’s the Japanese Immersion Programme.

And for the first, I want to say it was like more than a year, it could have been two years, but let’s say a year at least, she attended that school. Eventually, she agreed to go across to the English, the Australian school. And so, she did end up learning English.

So it was just in that initial sediment period where she was kind of digging her heels in about, no, we’re not staying here, we’re going back to Japan.

Brynn: And that idea about a person’s identity is so interesting. And a big topic in the idea of migrant settlement is this idea of creating a new home, achieving belonging. You’ve spoken about this particular person’s trajectory in achieving this linguistic belonging, especially with her own daughter.

Can you tell us more about what you found about other participants’ identity trajectories?

Dr. Butorac: One of the things that I always come back to, because I found it so fascinating at the time, was the way that a couple of the women found that even early on when they were at best intermediate level English proficiency, they found that they were a much more confident person when they spoke English than when they spoke their primary language, which turned my thinking on its head because I thought, well, surely confidence is about proficiency. And why would you feel more confident in English, which is not your best language? And it wasn’t really about proficiency.

It was about perhaps the affordances of the culture that they were using English in and that this was tied up with using English and speaking it. So, in both cases, those women were Japanese and and they spoke about the stress of navigating norms of respect in social interactions in Japanese and also the ways that they felt restricted by the gender subjectivities for women in Japanese society. And one of these women talked about having many masks in the drawer and having to decide which one to put on each day.

And so, these women felt that to speak English meant they could be a different kind of woman and more socially confident woman. And they quite liked this. So that was that was really interesting to me.

But that was something specific to those women. And I think the other woman who had spent time living in Japan could relate to some of that thinking. But the women who came from European backgrounds didn’t feel that kind of shift at all.

They weren’t able to perceive that their identity was shifting from learning English. What they felt was in the beginning, they said, I’m still the same person. I just can’t express myself very well in English during those early stages.

But what they did experience over the course of the project was that their development of a voice in English. So, they got better at speaking English. And by the end, they could see they could hear themselves that it had begun to impact how they spoke their primary language.

So, they’d be telling me about, well, I was back in Russia, I was back in Bulgaria and I’m talking to people and they particularly noticed it in transactional encounters. So, they go to the shops or something and they said, oh my God, I’m finding that I’m saying, please and thank you a lot more. And you don’t do that in my language.

People look at me funny, like, why are you saying please? So, they’re using this English sensibility that they develop from being here in this kind of culture. And by the way, they all would say, oh, it’s so much more polite here. And I’m like, really, you’re serious? I don’t see it that way. But anyway, but they found themselves being that kind of person in their language, which was odd.

I mean, one of the Japanese women, it wasn’t so much about politeness. That was really what the European women spoke about. But one of the Japanese women said, I feel like I’m becoming this weird kind of Japanese person because I go back there and my sister’s looking at me funny because I’m saying things like pigs don’t fly, which we don’t say things like that in Japanese.

But I’m saying it in Japanese, but it’s something I developed from being in Australia. And so, I’m becoming a strange Japanese person. One of the things that I did also find interesting because I think they all felt that being a woman in Australia was a good move.

It was good because of the rights and affordances. You know, there’s equality, gender equality and all that kind of thing, which was great. So, I know one of them in particular had all sorts of aspirations about what she was going to be and what she was going to do.

But what I found interesting over the course of speaking to them all was that, yes, they all had the sense that women in Australia are quite liberated and quite independent et cetera. But they couldn’t necessarily kind of appreciate all those affordances of those rights because of things that get in the way of that. So, one of them was the monolingual mindset in the labour market, which privileges just the use of English.

And so that meant, you know, success in the labour market was going to be impacted by proficiency in English. Also, the kind of qualifications, gatekeeping that goes on in the labour market. So, it means that their prior qualifications and lots of years of work experience weren’t going to be recognised and would mean that they’d have to go back and do all sorts of new qualifications in order to work here.

And the other factor that limited some of the women was prejudice in the labour market that can make it harder for people from outside the Anglosphere and from Western Europe to be able to achieve success in the job market. And in my study, that was felt by women from the woman from China. There’s another Chinese Brazilian woman and also the women from Japan.

They felt often quite despondent about their, you know, their chances of actually being able to get meaningful work or advance within a job in Australia.

Brynn: And that is such a powerful theme in the book throughout many of the author’s studies. When you read the book, you can see that there is this huge overarching theme of difficulty in entering the workforce, the labor force in Australia.

If you’re coming from a different country with a different language background (and you don’t have to achieve world peace in your answer to this question) – But just kind of for you, how do you think we could improve things to make it easier for these new migrants? Whether it is being mothers, whether it is being language learners, or if it’s entering the labor force, what should we as English speakers be doing in Australia?

Dr. Butorac: I feel like the society in general, one of the big things that has to shift, but it’s a societal wide shift, is that monolingualism, that idea that you’re only judging someone’s English capacity. You’re not seeing the full person. And I feel like if we recognized a person’s full language capital, then that would make us judge them differently in terms of going for jobs.

That’s one thing. And also, the qualifications recognition. I mean, that thing that needs to be loosened up.

Even like me coming from Canada with my post-grad TESOL from Canada, it wasn’t recognized in Australia.

Brynn: The same thing happened to me. I had a CELTA certification from Europe. And when I came over here to teach English in Australia, I had to re-certify.

Dr. Butorac: Yes. The only person I struck, like colleague I ever struck, who didn’t have that problem, came from the UK. There seemed to be full recognition of her prior qualifications.

And I was a bit surprised at them not recognizing my TESOL diploma because I thought it’s from Canada, a very similar education system to here. How does that not even appeal to you? But no, it had to be it had to be assessed.

They did a bad job of that first. I had to challenge that. They had to go back and then do a very lengthy – It took months, which really surprised me. So, yes, that is a problem for many people.

The other thing I think we could do within the Settlement English program, and this is just based on, I guess, responding to the findings from my own study, is help new migrants navigate some of the more challenging aspects of getting a job.

And so, I’m thinking, we should be using what we’ve learned from research to inform students about what to expect. So, for example, we know from previous audits of the labour market that there is prejudice that favors hiring people from within the Anglosphere. So, some people are more likely to get an interview call back from a job application than others.

And this is a function of their ethnicity. But we never tell students this. We just pivot a lot of their English language development towards being able to get a job on the assumption that all they have to do is develop their English.

So, they have better English proficiency. So, when students aren’t successful, they assume that it must be them, must be their English. When in reality, it is quite likely that their life of success is about the prejudice of the company that they’re, you know, trying to hire into.

And I feel that if we could first be open about having an honest discussion about racism in the labour market, this could pave the way to being able to advise students on strategies for dealing with this. And I think back to that study from 2009, I think, that Booth, Leigh and Varganova did an audit of the labour market by applying for over 5,000 jobs and so on. And one of their main findings that stuck with me was if you’ve got a Chinese last name, you have to apply for twice as many jobs as if you’ve got an Anglo last name in order to get an interview call back.

And I thought, why are we not telling students this? And it’s like, OK, so then they can at least strategise. All right, so I have to just keep applying because I’ll have to apply for twice as many.

You know, I know that’s a really simplistic way of looking at. But I feel like, why not pass on this kind of information that we know from research, pass it on to the new migrants in the settlement program so they can figure out how to manage that reality? Because this assumption that it’s just about your English is not good enough.

And it makes them blame themselves. And I’ve seen that time and again, you know, they go, it must be me, you know, there’s something wrong with me.

It does. And that kind of goes back to what you were saying about how your participants had sort of this idea of an Australian woman or maybe Australians in general or Australian society and what the society is and the freedoms that it affords. And this kind of puts that into sharp relief, you know, it’s quite a contrasting idea.

But you’re right. I think it’s important that we’re at least honest about it.

Dr. Butorac: Yes. Yeah. But I think and so maybe that’s just a question of within the practical front, you know, the coalface of teaching language.

We should be connecting more with the research that lies behind some of the thinking and what we know about, you know, society from applied studies, you know, from the sociolinguistic studies that have been done, particularly in migration and settlement experiences and trajectories and so on.

Brynn: I agree. I really love that answer. Let’s shift a little bit to the actual co-authoring of this monograph.

So you and five other people co-authored this book and that to me, and I have done group projects before, that sounds really hard. What were the ups and downs of the writing process for you? How do six of you do this, especially during a global pandemic?

Dr. Butorac: Yeah, the pandemic was probably a bit challenging. But, you know, to be honest, it was really more up than down. And I think this is a great way of doing academic work for me.

I really enjoyed it. And this is not just for the ability to work with the larger sets of ethnographic data, which obviously it enabled us to do, but also for the joys of collaborating with colleagues. You know, it’s really nice.

And it does, of course, rely on, you know, people being able to work well together. But I think our team is really wonderful. So, for me, it was always a joy to meet with my colleagues.

And I think we’re all quite different. But I feel like we complement each other really well. You know, academically, we’re not all at the same stage in our careers.

Of course, Ingrid is in a much more senior role to all of the other co-authors. But that has felt more like an opportunity than a problem. And I think we also see each other as social equals.

And so, we’re able to have a good laugh together as well as work together. So, yeah, I really loved it. I think the only downside for me was the physical distance, which was worse during COVID when we couldn’t travel, especially in and out of Western Australia.

But we still connected online. It was that physical distance because most of the colleagues, and it’s the same for Emily. Both of us live outside Sydney.

We’ve taken every opportunity we could to gather in person. And I always feel such a personal and professional boost when I meet these women. And I remember thinking back in that first workshop, I remember thinking professionally, these are my people.

I had a real sense of being at home then. And I think that’s because I’d been feeling a bit isolated at work. Perhaps because anthropology and sociology, I had moved into teaching in the faculty.

It’s quite a small program at Curtin. And so, to be in the room with these women, and most of them I’d met while I was doing my PhD at Macquarie, and being able to continue working with Ingrid. And we’d all done research in a similar broad field.

It was really affirming for me. It’s always been a really positive thing. I love it.

Brynn: That’s really lovely. I love that answer. And I feel the same way with the Language on the Move research group at Macquarie University.

I love gathering with those people. I love the camaraderie that we have, not just as fellow academics, but many of us as women, several of us as mums who are also doing all this academic work. And it really does feel like an opportunity to network with those people, but also develop friendships and relationships, which I think is really important in academia, which can be a difficult sphere to work in.

Dr. Butorac: Oh, it can.

And I think a lot of that is to do with Ingrid’s personality and her desire to create this kind of sociality, because you don’t always see this with academics. And I feel like I’ve learned a lot from being supervised by Ingrid and from watching the way she does bring people together, her students, her former students, and create a social world around it. And that creates opportunities for people.

And I think that’s really wonderful. And you don’t see enough of that. But I think this collaborating idea is so great.

And to be able to combine your different research projects in that kind of collaboration to create this bigger data set is really exciting, actually. It’s a new way of looking at ethnography.

Brynn: And honestly, it makes for a really good book. I read it and it’s great. So, I applaud that.

And before we wrap up, can you tell us what you’re up to these days, kind of post-authorship life? I know you’re a senior lecturer. Can you talk to us about what you’re currently teaching?

Dr. Butorac: Yeah, sure. Well, I’m in a teaching-focused position. So mostly what I do is teaching and supervision for about six years.

This is the first year actually I’ve returned to just teaching and supervision because I was also doing leadership roles at the school level for about six years. But it’s really been nice to sort of be immersing myself back more fully in the delivery of the programs and having more direct contact with students. But one of the things I did soon after I joined the faculty, and which I’m quite proud of, is I created a new unit that explored the sociology of language, because this was an area that was quite missing from the major, and the unit’s called Language and Social Life.

And it explores theory and research in a range of topics from the sociology of language, as well as skills development in doing research. So doing qualitative research that focuses on language ideology and use, so looking at frameworks for doing discourse analysis and things like that, working with datasets. And so, in the sociology of language, there’s topics on gender and language and language ideology, race and power and language and culture and things.

There’s also topics from my collaboration with Ingrid, and also other scholars that I’ve met through the Macquarie University connection. So, for example, there’s one topic on linguistic diversity and social justice, and that draws heavily from Ingrid’s publication on that topic. And then another topic that I brought in a couple of years after I’d started teaching it was the result of going to a symposium at Sydney University that was organised by Laura Smith-Kahn and Alex Grey.

And that really opened my mind to some of the fantastic research that’s been done in things like forensic linguistics and in understanding how language ideologies mediate criminal justice and asylum claims hearings. And so that topic is called Language and the Law. So we just look at a whole range of things in there.

So yeah, it’s been this collaboration and the connections with people that I met through Macquarie has influenced that unit and inspired some of the work that goes on there. But I love that unit, I love teaching it.

Brynn: That unit sounds awesome. I might have to show up there as a student because it sounds really good. And I agree, I love teaching as well.

I get to be a tutor in undergrad courses every other semester. And I just really, really like it. I feel like I go back to my roots in that way because I feel like that’s how I was trained was to be a teacher. And I really love doing it. So, I agree, I think it’s a really important part of what we do.

Dr. Butorac: Well, it is and it’s quite impactful. I thought years ago when I was sort of going, oh, I should be publishing more. And then I thought, you know what, I could publish something that 10 people might read if I’m lucky.

But I’ve got 80 people standing in front of me right now and I can speak directly to them. And that’s meaningful.

Brynn: That is meaningful. And that’s a beautiful way to end. Thank you for chatting with me today, Donna. I really appreciate it.

And thank you to everyone for listening. If you enjoyed the show, please subscribe to our channel. Leave a five-star review on your podcast app of choice and recommend the Language on the Move Podcast and our partner, The New Books Network, to your students, colleagues and friends. Until next time!

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a