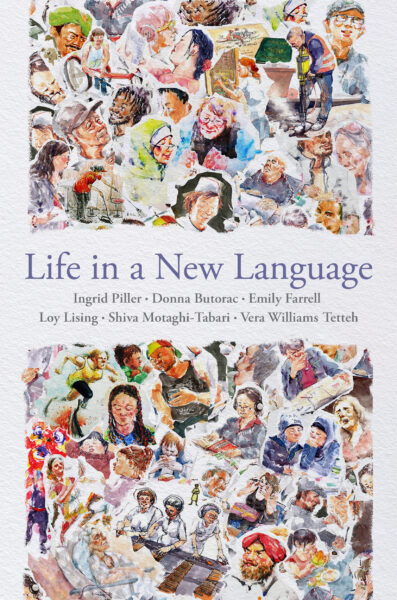

This episode of the Language on the Move Podcast is Part 2 of our new series devoted to Life in a New Language. Life in a New Language is a new book just out from Oxford University Press. It is a project of Language on the Move scholarly sisterhood and has been co-authored by Ingrid Piller, Donna Butorac, Emily Farrell, Loy Lising, Shiva Motaghi Tabari, and Vera Williams Tetteh.

Cover art by Sadami Konchi

International migration is at an all-time high as ever more people move across national borders for work or study, in search of refuge or adventure. Regardless of their motivations and whether they intend their moves to be temporary or permanent, all transnational migrants face the challenge of re-building their lives in a different cultural and linguistic context, far away from family and friends, and the everyday routines of their previous lives. Established populations in destination countries may treat migrants with benign neglect at best and outright hostility at worst.

How then do migrants make a new life?

To answer that question, Life in a New Language examines the language learning and settlement experiences of 130 migrants to Australia from 34 different countries in Africa, Asia, Europe, and Latin America over a period of 20 years. Reusing data shared from six separate sociolinguistic ethnographies, the book illuminates participants’ lived experience of learning and communicating in a new language, finding work, and doing family. Additionally, participants’ experiences with racism and identity making in a new context are explored. The research uncovers significant hardship but also migrants’ courage and resilience. The book has implications for language service provision, migration policy, open science, and social justice movements.

Today, Brynn chats with Ingrid Piller, one of the book’s six co-authors, with a focus on migrants’ challenges with finding work.

Use promo code AAFLYG6 for a discount when you purchase from Oxford University Press.

Advance praise

“This volume breaks new ground by focusing on Doings: a group of diverse researchers collaboratively doing close listening and looking over 20 years, as adult immigrants to Australia engage in doing life, things, words, family, and work in a new language. The result is not only new understandings of the participants’ self-making, but also the making of a new research trajectory that focuses not simply on the learning of a language, but on humanity doing life in language.” (Ofelia García, The Graduate Center, City University of New York)

“This is a moving book that represents the voices of migrants on their challenges and successes across different kinds of boundaries. It embodies impersonal structural and geopolitical pressures as negotiated in the dreams and aspirations of migrants. The authors share findings from decades-long separate research projects to develop richer insights, as a model for data sharing and ethical research.” (Suresh Canagarajah, Pennsylvania State University)

Transcript (by Brynn Quick, added on July 03, 2024)

Brynn:

Welcome to the Language on the Move podcast, a channel on the New Books Network!

My name is Brynn Quick, and I’m a PhD candidate at Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia.

Today’s episode is part of a series devoted to Life in a New Language.

Life in a New Language is a new book just out from Oxford University Press. It’s co-authored by Ingrid Piller, Donna Butorac, Emily Farrell, Loy Lising, Shiva Motaghi Tabari, and Vera Williams Tetteh. In this series, I’ll chat to each of the co-authors about their perspective.

Life in a New Language examines the language learning and settlement experiences of 130 migrants to Australia from 34 different countries in Africa, Asia, Europe, and Latin America over a period of 20 years. Reusing data shared from six separate sociolinguistic ethnographies, the book illuminates participants’ lived experience of learning and communicating in a new language, finding work, and doing family. Additionally, participants’ experiences with racism and identity making in a new context are explored. The research uncovers significant hardship but also migrants’ courage and resilience. The book has implications for language service provision, migration policy, open science, and social justice movements.

My guest today is Ingrid Piller.

Ingrid Piller is Distinguished Professor of Applied Linguistics at Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia. There is so much I could say about her prolific academic work, but for now I’ll introduce her as the driving force behind the research blog Language on the Move and the lead author on Life in a New Language.

Welcome to the show, Ingrid!

Dist Prof Piller: Hi, Brynn.

Brynn: To get us started, can you tell us a bit about yourself and how you got the idea for Life in a New Language?

Dist Prof Piller: Yeah, sure! Look, I’ve been researching linguistic diversity and social justice for like 30 years. So, the key question of my research has been like, what does it mean to learn a new language at the same time that you actually need to do things with that language? So that it’s not just a classroom exercise.

It’s not just something that, you know, you do for fun, but you actually need to find a job through that language. You need to, I don’t know, get health care. You need to rent a house. You need to get a new phone contract. You need to go down to the shops. You need to, you know, make a new life, make new friends.

And so that’s sort of been the key question of my research in various aspects for a really long time. And sort of around in the mid 2010s, I kind of felt like I’ve been doing so many projects in this area. My students have been doing so many projects in this area, and we really should actually pool these resources and these findings and all this research that’s sort of all over the place and bring it together in one coherent systematic exploration of what it actually means to simultaneously learn a new language and have to do things through that language.

And so that’s the story behind the book.

That’s such a big part about starting a new life in a new language. And I think a lot of people don’t necessarily realise that. They sort of separate the idea of language learning and life, and they don’t tend to think of the two together.

Brynn: And something that you’ve just mentioned is about how you had students, other people that you were working with throughout the course of all of these years, who were doing this type of research. And the book, Life in a New Language, is all about the reuse of this ethnographic data. Can you tell us about the original research project that your contribution is based on?

Dist Prof Piller: Okay, so I supervised each and every one of the projects. That is actually the basis. So, in a sense, I’ve had a finger in the pie of each of the research projects that we brought together in Life in a New Language.

But the sort of the one key piece of data that is mine, if you will, came from a research project that I did or that I started in 2000, so 24 years ago. And the interest there was to understand how people achieved really high proficiency. And at the time, I just finished my research with bilingual couples, where, you know, one partner comes from one language background, the other partner from another language background.

And one thing that came out sort of as an incidental finding in that research project, amongst many, particularly of the German participants I had there, is that many of them were sort of often like testing themselves if they could pass. So, they spoke about these passing experiences, like, you know, they, I don’t know, they’ve gone to the shops and someone had asked them like, Oh, are you from some other city down the road in the UK or something? And so hadn’t realized straight away that they had a non-native accent.

This was sort of an incidental finding that people or high-performing second language speakers were really interested in these passing experiences. And so, I kind of thought, Oh, that’s an interesting research project. And let’s do that as a separate research project.

And I got some first internal research funding from the University of Sydney, where I worked at the time, and then later from the ARC to actually investigate high-performing second language speakers. So, people who identified themselves as having been very successful in their second language learning. And so, I conceived that as kind of an individual ethnographic study, mostly an interview study.

And so, we started by just distributing ads and asking for people who thought they’d been really successful in their English language learning here in Sydney. And, you know, lots of people put their hands up in interesting ways, actually. And some of them then when we actually spoke to them, we usually started the conversation with like, you’ve put your hand, been highly successful in second language.

And then they go like, now you tell me whether I’m highly successful. So, it was kind of, you know, really, really interesting. And then the data that we collected from that project over a couple of years also became part of life in a new language.

Brynn: That’s so cool because I feel like we very rarely have those research opportunities with people who feel like they have been successful in the language. I feel like so often, I mean, rightly so, we do a lot of research with people who might feel like they’re struggling with the language.

What did you find with them just out of curiosity? Was there any sort of through line?

Dist Prof Piller: One of the most interesting people on that study, and someone I sort of went from participant to friend, was a guy who’d signed up. And when we interviewed him, the first interview we did, I did that together with the research assistant, Sheila Pham. And we had this conversation.

We were chatting about all kinds of things, like, you know, his language learning stories. He was from Shanghai. He was really like extrovert and kind of talking a lot about how Shanghai is so great and Sydney is so boring and provincial by comparison.

And anyways, after we’d done that interview, Sheila and I, we looked at each other and it was like, we found the Holy Grail. We found a second language speaker who started to learn English actually in his early 20s and, you know, who’s indistinguishable from a native Australian speaker. Doesn’t have an accent.

And it was like, oh, wow. So, you know, so this is going to be like our focal case. And we’re so excited.

Next thing we did, we transcribed the interview and looked at it on paper. It was actually, I mean, it wasn’t good at all. Like, I mean, there was so many like grammatical errors.

You know, if you look at it like in terms of grammar, in terms of syntax, anyway, it wasn’t high level actually. So, there was a complete mismatch in a sense between the performance, the oral performance of this person, which was like, you know, as I said, indistinguishable. We both agreed and we then, you know, got other people to kind of assess him as well.

Everyone sort of agrees, you know, no, wouldn’t have realized that he hasn’t grown up in Australia. If you actually sort of look at it from like a grammar perspective, no, that is really, really fascinating. And in many ways, I didn’t do enough with that case study because I went on to do other things.

But the kind of embodied performance, the way you behave, the things you talk about that is really, really important. And as language teachers or in, you know, in TESOL, we often think so much about accuracy. But in many ways, accuracy isn’t really so important in language.

And so, language is never only about language. I guess that’s one of the key messages of this book and also of my research. I mean, language is OK, we’re linguists, but language is never just about language itself is not interesting.

What is interesting is what people do with it and how they become different persons in a different language or how people react to them and how we kind of organize our society as a linguistically diverse society. So, it’s really the sideways looking, the social aspect that interests me as opposed to like what’s going on with the grammar.

Brynn: Yeah, and I think that’s so important to keep in mind, especially when we think about people who are doing all of these things with language in maybe a new place, especially in this participant’s case, being in their early 20s, starting to learn English and something that you have to face in your early 20s is the idea of work. And that’s something that is a big topic in the book, Life in a New Language is the idea of settling in a new place and finding work. So, can you tell us about what you found about the participant’s employment trajectories in the book?

Dist Prof Piller: Yeah, so that was a really, really big topic and employment work came up really across the data, even if the initial focus of data collection or of the study had not been about employment. Like, I mean, as I told you, the focus of the data I brought to it had been high performance and high-level proficiency. Employment came up for everyone is really, really big topic.

And that, of course, relates to some. I mean, it’s not entirely surprising. It relates to something we know from the statistics that amongst migrants, there are much higher levels of unemployment and underemployment than there are amongst the native born.

And underemployment means you have work at a lower level than for which you’re qualified or you work fewer hours than you want to work. And both unemployment and underemployment are really high. We know that in the typical explanation that is given for that is that we find like in the business literature, the migration literature is, you know, migrants.

English isn’t good enough, so they’re struggling with language. That’s a barrier to their employment. Their qualifications aren’t good enough.

You know, they’re not as strong or as high as qualifications of people trained in Australia. So essentially, the explanation is migrants have a human resource deficit. To me or to us as the authors of the book, this has never been entirely convincing.

And the reason I don’t find that convincing is that in Australia in particular, the migrants have a particular, bring relative high human resources to Australia. And to understand that I need to say a few things about Australia’s migration program, because Australia’s migration program is essentially organized in re-streams. And that’s a real simplification because at any one time during the 20 years we did this study, there were like close to 200 different visa types on the books.

But all these different visa types essentially fall into three categories. One category is related to skills. So, you get a visa to Australia because you bring something to Australia.

So usually that’s your professional skills, work skills. You can apply as an individual migrant, like many of our participants came from Iran. So, let’s say you are an IT engineer in Iran.

You are like in your late 20s or early 30s. You have a bit of professional experience. You’re interested in migrating to Australia.

You put in an application and you get points for your qualification and also for your English. So, in order to come in under the skills program, most of the skilled migrants need English. And the skilled migration program takes up, and that can be temporary or permanent, so lots of variations.

But essentially everyone in that program needs English. There are a couple of exceptions. Like if you bring a lot of money, you do not necessarily have such great English.

But overall, we can say like around 80% of our migration program are people who come in for their skills. And part of that skills is actually they need to show they have high levels of English language proficiency. Then the other two groups and they are much smaller are family reunion migrants and humanitarian entrants.

So, these people get their visa because for family reasons, so because they are the spouse of an Australian citizen or the parents of an Australian citizen, or for humanitarian reasons because they deserve our protection and chief refuge in Australia. Now for these two groups, they don’t need to demonstrate English language skills because they are assessed on something else. But that doesn’t mean that they don’t speak English necessarily, right?

I mean, so it’s true that, you know, many family reunion migrants do not speak English, but at the same time, they may have learned English already, right? And the same for refugees. I mean, one thing that we found amongst the refugees in particular was that many of them were really, really highly qualified, spoke English, had been educated through English, particularly from various African nations, post-colonial nations.

And still they were always seen like they’re refugees. They haven’t got any qualifications. They don’t speak English.

So that’s not the truth at all. Now, to go back to the original point that I was making is that we have these people who come in under these different visa categories. For most of them, they need to demonstrate English to even get into Australia.

So why then, once they’re here, they don’t actually find jobs because their English isn’t good enough. Something doesn’t add up there. And so, what we found was that English actually becomes like this global criterion on the basis of which you read people are excluded from the job market just because you don’t want them or it becomes like every employer, every person who has anything to say takes it upon themselves to pass judgment on the English language proficiency of newcomers, regardless whatever their qualifications are. I mean, they usually have no qualifications whatsoever, but still they go, Oh, your English isn’t good enough.

And so, we found things like, I mean, one participant, for instance, from Kenya, she was applying for like receptionist jobs. And so, she was having an interview with a small business and small business owner goes, Look, I love you. You’re fantastically qualified, but I can’t really have you as a receptionist because my customers won’t understand your English. Now her, I mean, she’s been educated through the medium of English. Her English is like Queen’s English, British English, very, very standard, very easy to understand.

I mean, maybe a bit of an East African little, that’s it. You know, this is fairly clearly a pretence for something else, right? And she was actually offered then kind of back-end work in the same company where she didn’t have, where she didn’t need that good English, but in reality, I think where she wasn’t in a customer facing role.

So that’s one thing you can, it’s illegal in Australia to discriminate against anyone on the basis of their national origin, their ethnicity, their race, but it’s not illegal to discriminate on the basis of language. And there really is no recourse. I mean, I can always tell you your English isn’t good enough, right?

And what can you do? I mean, that’s one issue there. Another issue around English language proficiency as this exclusionary criterion is that it’s simply applied holus bolus regardless of the job you’re applying for.

And so, we had a couple of fairly low educated people in our study who objectively didn’t speak a whole lot of English. And they weren’t aspiring to like, you know, language work. They were looking for like cleaning work and couldn’t get cleaning work because people told them or employers told them your English isn’t good enough.

And so, what was going on there essentially is in order to… And they were going like, you know, I’m like one participant, she was from South Sudan and had sort of a complicated migration story, had lived in transit in Egypt for like a decade. And she was saying, look, I mean, in Egypt, I lived like the Egyptians. I was cleaning houses. I was looking after children and it wasn’t difficult. I can do that. And that’s all I want to do here. I want to clean people’s houses. I want to be a cleaner. I want to maybe look after children. But really, she was aspiring to cleaning. But wherever I go, they tell me, your English isn’t good enough.

And she was like, part of that is that you actually in Australia, you need certification, right? Like if you’re cleaning, you need some certificate that you’re not going to mix up the various cleaning products so that you know how to do that hygienically. And that’s really difficult to do if you have low levels of literacy.

And so there were these like really artificial barriers where English kind of becomes an intermediary artificial barrier to doing work you’re perfectly qualified for and you have the right language for. And so, I mean, I’ve spoken a bit about cleaning now, but we sort of also have that at the other end of the spectrum, like another of our participants. She was really, really highly proficient.

She had studied English all her life, had an English language teaching degree from Chile, then had been on Australia for quite a while. And she was retraining as a TESOL teacher and trying to get an MA in TESOL to become an English language teacher. And that was like 20 years ago.

So, it may have changed now. But anyways, she needed to do an internship as part of her degree. And she just couldn’t get a practicum place.

And she tells the story that, you know, she was calling up one. I mean, it’s just like, I called up every TESOL and every ELICOS and every language school in Sydney. And they’d always say things like, oh, yeah, we don’t have a place at the moment.

Or, you know, can you call back again like next year or whatever? And she had this one story where she said, on a Monday, I called this particular school and, you know, I asked, can I do my practicum there? And the person in charge told her, no, we are full for this term or whatever. Call back again next year, next term. And on Wednesday, she spoke to a classmate and the classmate said, look, I’ve just called this particular school this morning and I’m going to do my practicum there. And so, it was like two days later, there was this space.

And the only difference between these two people was that, you know, our participant was from Chile, spoke with a bit of a Spanish accent. And the other participant was, she called it Australian. And when our participant said Australian, it was always native-born Anglo-Australian.

So really the absence of this accent was the, and so that’s the only explanation. So she gave up on the TESOL degree because she kind of said, look, if I can’t even get an internship to graduate, how am I ever going to find a job, right? And so, yeah, language is this really, so in a sense, we, it’s not migrants who have an English language deficit.

It’s actually that we create artificial barriers through making language proficiency, this kind of global construct that is this big barrier, and then apply it whenever we sort of have any kinds of concerns or prejudices or just don’t need that person, whatever. It becomes the explanation for everything, but that really doesn’t do anyone any favours. And I think that’s where one of the important lessons of the book is we actually need to unpack what it means to speak English well, to speak English so that you can do a particular job you’re aspiring to, because that is beneficial, it’s beneficial for the economy. It’s beneficial for everyone, right?

Brynn: And that’s what is so interesting to me is when you talk about “we” in that context, you know, we need to remove this artificial barrier. And a lot of times I think about that in two different ways.

One is sort of the more policy driven. So, like, people in the government, you know, things that we can do policy-wise that would remove those barriers. But then another thing that I think about is just kind of your average person, especially your monolingual English speaking, in this case, Australian, all of these things that these participants have had to go through sounds so difficult. How can we, and this could be, you know, either or, the policymakers or sort of your average Joe on the street, how can we improve things to make it easier for migrants to come to Australia, whether they have this high level of English or not, but to find work and to begin to settle?

Dist Prof Piller: Look, that’s a good question and it’s of course a difficult question and one that our society has been struggling with for years and decades. And overall, I guess we also need to say that Australia is actually doing things pretty well in international comparison. I think that’s always important to keep in mind.

I think it’s a lot harder in North America, a lot harder in Europe, but in different ways, I guess. And so, what’s the lesson for us here? I guess in terms of policy lessons, one thing would be that we need a better alignment across different decision makers, because one thing that we found is particularly with those independent, skilled migrants, once they received their visa to Australia, because they’d gone through that process, you know, they put in their application, they demonstrated their qualifications, they’d done their IELTS test and sometimes, you know, a number of times and kind of should I’ve got the right IELTS score.

So, they’ve done all these things and then they received the visa and they kind of felt like, you know, the Australian government is now telling me I’m ready, I’m good to go, I’m welcome, I can make a contribution to this society. And then they arrive and it’s nothing like that, because all of a sudden there are different bodies that make decisions over their qualifications. And so, for instance, like with all the medical professionals we spoke to, that’s a huge barrier.

So, they get their visa and then they come here and then they need to be re-accredited. And the re-accreditation process is independent from the government visa process. And so all of a sudden, it’s actually not so straightforward.

So, one of our participants, it’s a really interesting story. So, she was a midwife from Romania and she had like 30 years of experience delivering babies. And so, she had the qualification from Bulgaria.

I think it was actually Bulgaria, but it doesn’t matter. So, she had like, you know, this four years training qualification. But in Europe, most of continental Europe, midwives are actually not trained at universities.

Like they’re here, they’re sort of hospital trained, but it’s also a four-year process. And, you know, they do a lot of theory at the same time. And so, she had that training and then she had experience for like 30 years working not only in her native country, but also overseas through the medium of English in the Gulf, somewhere in the UAE.

And there she met her husband an Australian, and they together moved to Australia when she was in her 50s. And she was totally optimistic that, you know, she would go on to deliver babies for another 10, 20 years until her retirement. And before they moved, she had looked up like job ads and seen, you know, there was a real midwife – I mean there is a midwife shortage and has been a midwife shortage in Australia for quite a while. They were moving somewhere regional in Western Australia. It was like, should be easy, very straightforward, and benefit both for the personal career of this woman, but also for Australia’s society. I mean, for our health care system, right? But that’s not how it turned out.

So, she arrives and they go like, I know your four years of hospital training, they’re not equivalent to what we do here. So, you need to do, and the 30 years practice experience, they don’t count. And so, you need to redo your midwife training. And that’s three years.

But because in Western Australia, every midwife is also a registered nurse, you first need to do your nursing degree. And so that’s like six years. And she was like, I’m in my mid-fifties.

I’m not going to study for six years also. My English is good enough to work, but it’s not the kind of English that I can write a big essay. I can’t necessarily go and study and be successful at university.

I can perfectly do the work. I have all the experience, but she ended up doing a phlebotomy course and now in a blood collection unit somewhere. And I’m just sort of happy that she’s still back in the hospital.

But of course, it’s a huge demotion. It’s extremely frustrating for her personally and such a loss for our society. And so that’s really where policy can do something, where you can actually create a pathway that you align the visa decision processes with the various professional qualification processes and also simplify professional qualification processes to the degree that you actually identify, like, what is the gap here?

I’m not saying, you know, everyone can work in whatever, not everything is equivalent. I mean, there’s no doubt about that. But like, what is the gap?

So, you’ve got this kind of level of training, you’ve got this kind of experience. So, maybe you need to learn something, something that is specific to Australia or that is specific to the way this role works here or, you know, whatever. But we really need to create those pathways.

And it’s not very difficult to map these things. But it shouldn’t be that we’re saying, like, you need to do all of your midwife training again and then on top of that, you need to become a registered nurse. And that’s just not feasible for people who are in middle age and, you know, who’ve done all their studies and all their qualifications.

Most people also needed to, you know, support their families and make a living and, you know, life is short. So, you just can’t redo something that you’ve already done. So, we really need to be much smarter about identifying the gaps and aligning decision-making processes.

So that’s one thing. You also asked about, like, what can individual people do? And I think, I mean, that’s where our book comes in, in a sense.

I mean, what we’re trying to create, I guess, is empathy for the challenge and the extreme courage it takes to actually make a new life in a new country at a time when, you know, your socialization, if you will, has already been largely completed in another place. So, to pivot to another world, it really takes a lot of courage, a lot of resilience. These are very bright people.

And so, yeah, empathy for this dual challenge. And just because someone doesn’t speak English all that well, that doesn’t mean they are stupid, right? I think that’s one of the things that we often see.

You just sort of feel, going back to this thing that we said earlier, people don’t necessarily understand what it means to learn a new language. If you have an adult who doesn’t speak English or your language well, you just see them as this deficit person, and you just see what they can’t do in English. You don’t think, well, they’re actually a whole other person in their other language, and they’ve got skills and knowledge, and they’re funny and interesting and whatever.

It may just be that they need a bit of help to express that in English as well. And so, we really need to treat people with a bit more compassion and empathy, I think.

Brynn: And I think that’s what this book does so well, is in pulling together all of these different participants from across so many different years, it really paints this picture of what we, as the English speakers in a dominant English-speaking country, what we need to keep in mind when we are interacting with these migrants. And on that idea, I think that this is a good time to mention that you co-authored this with five other people. So, there were six people total that did this, and you all brought your own studies and your own participants and your own research to kind of paint that picture.

But what I want to know is what was that like to work as a group of six? What were the ups and downs of the writing process? How did you even go about doing that?

Dist Prof Piller: Look, I mean, one thing, in addition to everything else we brought, in addition to our research, we also brought our lived experience. So, four of us actually have this experience of moving to Australia as adults. And so, I think that’s another dimension that we brought to it as people who had also been on that journey and rebuilding our lives here.

So, what was it like to co-author? It was a lot of fun. It was also a lot of work.

So, I guess these are the two things. So, one thing people might think like, you know, you have six people to author a book. So that’s like, you know, a sixth of the work.

And so, it should have been really quick. That’s not true at all, I would say. And I mean, I’ve written a couple of books as a sole author.

I would say this was more work. On me as an individual, I contributed more and that’s true for all the other five authors. So, it’s hugely inefficient in a sense.

But at the same time, it’s not at all because, you know, none of us individually would have been able to write this thing. So it really needed the collaboration. And that’s another that’s a reason I’m really proud of that book, because I think it does something that we don’t do often enough in our field, where you sort of have this collaboration and joined.

You know, you share your data, obviously, but do your analysis together. You do your writing together. And that really is much more than the sum of its parts.

And I mean, one decision that we made, like right at the beginning of this is we don’t want this to be like an edited book or we don’t want this to be just, you know, each of us writes a chapter and then we kind of all go over it and adapt it a bit. We made a decision that we wanted this to be our combined voice, if you will, that we write in a particular voice. But we do this really together as, you know, you couldn’t say like, oh, this part is written by Ingrid and this part is written by Vera or something like that.

So that’s not how it works. And what we’ve achieved in the process is something that, you know, I think is a real advance or a real innovation in qualitative research, that we’ve actually been able to kind of add generalizability to ethnographic research, because, you know, usually you don’t expect ethnographic research to be generalizable. And that’s how it works.

But by actually pooling all these resources and redoing the analysis, based on new codes and new research questions, we’ve been able to paint a much broader picture. And I think that’s, you know, that’s actually quite fantastic. And I’m really, really happy with that.

And in terms of fun, it really, I mean, it took a long time. It was hard work. But it’s also great, actually, to work on something together.

Like if you have the Sisyphus Project where you always feel like, you know, you need to push and push. If you do this together and celebrate things together and kind of be able to laugh about things and kind of end the day on a little WhatsApp chat about like, what have we achieved? What haven’t we achieved? Where have we gone backwards? That’s actually good. So, it really keeps you motivated and it kept us going and was actually, I mean, it took longer than expected. And I think that’s fair enough.

Brynn: And I really do too. I think it’s so important in our field of academia to encourage that collaboration and to celebrate that collaboration, because it’s not something that tends to get done that much in academia. And it’s just so nice to see that sort of positive collaboration happening because then that could happen more.

That could happen more between more authors, more researchers to give us these more generalizable ethnographic studies, which I think are really important, like you said, to paint that picture for people. And this book is really readable. You don’t have to be a linguist to enjoy this book or to learn something from this book.

And I think it’s important to say that because it is something that even monolingual English speakers can really learn from through all of these stories that come together. And just before we wrap up, can you talk to us about your next project? What are you working on now?

Are there going to be more books? What are you up to?

Dist Prof Piller: I’ve always got too many things on the boil. But one thing I really want to keep going is this kind of collaboration, I guess, and doing things together. And one more, one more harking back to your previous question, like, what was this like?

I think academia can be quite hard on people, particularly on early career researchers. And there’s always this pressure to perform. And, you know, how many articles have you published?

And how often have you been cited and whatnot? And by actually building a community. And I think, you know, we’ve built an author community and a community of practice with this book.

But Life in a New Language is also part of this broader community that we’ve built with Language on the Move and the various PhD projects and research projects and collaborations and all kinds of directions that are going on there. And so that really is important for me to keep going, to continue all these various joint projects that we are doing. And, you know, this podcast is, of course, another one of these projects that I’m very excited about that, you know, you are taking forward in such wonderful ways and that we’ve only just started quite recently.

In terms of my individual writing, the next thing I’m working on is actually the third edition of Intercultural Communication. So that’s this textbook that I originally wrote in 2011, and that’s been doing really well. And so, the third edition is almost ready, and it will include a new chapter on health communication and sort of the lessons that we’ve learned for intercultural communication from the pandemic.

Brynn: That’s very exciting to me, particularly, because as you know, as my supervisor, that is what I’m working on on my PhD. So, I’m very much excited to hear that. That’s awesome.

Ingrid, thank you so much for chatting. Really, really appreciate you taking that time and talking to us about the book today.

Dist Prof Piller: Thanks a lot, Brynn. It’s been a lot of fun. Thank you.

Brynn: And thanks for listening, everyone! If you enjoyed the show, please subscribe to our channel, leave a 5-star review on your podcast app of choice, and recommend the Language on the Move podcast and our partner the New Books Network to your students, colleagues, and friends.

Till next time!

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a

I completely sympathize with Franklin having undergone such emotional turmoil of being erroneously directed to enroll in English – language study when he was competent English language user. In addition to that There are two clear problems seen in Franklin’s scenario: the first is the non-recognition of his prior academic qualification and secondly his experience. Although those experiences and qualifications were attained in another country, it is totally unfair to totally dismiss them, in fact it is referred to as “unassessed” deficit. If they are to be measured, what standard are they being measured against? These problems snowballed for Franklin resulting in him not been able to secure employment or rather employment that was equivalent to his qualification. I find this a major problem for migrants here in Australia. The system in place is prejudiced against migrants especially those who come from non-native English-speaking countries. I feel that those who develop these rules for migrants such as English language proficiency and assessment of prior knowledge (qualifications) and experiences should be professionals in this field for they will know best the standard one must be at or the best assessment, if any, that migrants should be given. I personally had this experience of the requirement to sit for IELTS test to be able to be granted a student visa. English is the main language of communication, formal language, and the language of instructions in all schools in Fiji. I had been an English teacher for 20 plus years and for the past 8 years until now, I am an English language curriculum developer, yet I had to sit for IELTS to be able to be get a student visa. That of course cost me AUD$335.00 which is expensive. Migrants will continue to encounter problems such as Franklin encountered unless there is a change in the system where prior knowledge (qualification) and experiences are recognized and accepted as is the system here at Macquarie University. I am a lucky recipient of that system here at Macquarie University as my prior knowledge and experience were recognized and considered hence I am only doing the 1 year version of the Masters in Applied Linguistics and TESOL.

Thanks! The cost to individual migrants and the profits for testing providers are substantial… glad your prior knowledge got recognised here at MQ.

After reading Franklin’s story, I became very emotional and felt a deep connection, as I am also a migrant and work casually here. I truly respect and admire his determination to overcome such difficult times. His story is filled with challenges—no English proficiency, no skills, and no qualifications—despite having all of these back in his home country.

I understand that this took place about 20 years ago, so regulations and policies were probably different from what they are today. Nowadays, English proficiency can be assessed through tests like IELTS or PTE. However, it would be hard for a refugee to take those tests as it costs about 450 AUD. Therefore, it would be helpful if the relevant authorities could provide the test for the refugees. In terms of skills and qualification, it might have been beneficial for him to take a TESOL course and obtain TESOL certification, which would have aligned with the experience he already had. Although, ELP might not have been as well-known back then, but still I think it’s a better choice than sacrificing 4 years for a bachelor degree.

Lastly, his story could be called ‘unfortunate’ but it would not have any relevance to a fortune if the policy changed and provided skill/career support to migrants/refugees.

Franklin’s story, sadly, is not unusual, and not restricted to his person or his time, as you point out.

Regarding job finding in Australia, immigrants and foreigners face many obstacles, namely language proficiency and the non-recognition of qualifications from domestic countries. I personally encountered the same problem when applying for jobs in Sydney, given that my language ability is adequate for basic communication as well as professional settings.

In my opinion, several intervention points can be implemented to tackle this issue. The government of Australia needs to conduct suitable evaluations for new arrivals to assess their proficiency in English before guiding them on their suitable path of careers. It is important to note that language proficiency has been demonstrated in the immigrants’ visa applications (via international language tests such as IELTS or PTE). Therefore, a better alignment across different decision-makers should be prioritized to avoid the situation of newcomers with qualified (on-paper) language ability getting rejected. Moreover, there should be more projects and programs on career consulting for immigrants. They will be given adequate information to be aware of the necessary qualifications for the jobs and prepare in advance instead of wasting time and money on the domestic qualifications without being recognised.

While reading Franklin’s story, I felt a deep sorrow and remembered I have heard other stories about getting dead end jobs in Australia. However, my Latin culture tends to romanticise suffering and many Colombians call this “a fresh start”. So getting these jobs is not considered bad but what it takes to be a migrant. Not complaining about losing your professional identity is a number one recommendation when Colombians speak about migration. They often say that you need to forget who you were in your country because one cannot compare a first-country education, experience or qualifications to a non-developed country. We normalise feeling inferior and we assume we are not as worthy. I did not even believe that I could teach English because I am not a native speaker. I have arrived in better times. I feel I can easily find a job in my field. However, this information is not easy to find. I was fortunately well connected and received help. Franklin did not have that fortune and here it is when the policies and governamental support come in handy. If Franklin had been given a a proficiency assessment he would not have wasted time and energy in attending a course he did not need. Also, a skills assessment could have taken place for him to know how relevant he is in this country and whether his qualifications allow him to teach. And I also believe a change of perceptions is equally relevant. We migrants are not inferior and neither is our education. Our experience is real therefore we should not ignore what we have learnt and can share. We are worth everywhere we go and on it relies the importance of diversity.

Thank you DaniG! I feel like underlining every word you have written!

I’ve often heard stories about people obtaining visas in Australia based on the skills they need for their development and many migrants often end up having a hard time to achieve a high level of English proficiency or underemployed due to a lack of English proficiency. However, Franklin’s story offers a different perspective on the real challenges refugees face when they arrive in Australia. I feel sorry for him because, despite his high level of English proficiency, he was not given a proper English assessment upon arrival. Instead, the case manager placed him in the AMEP. If there were a system or individuals dedicated to truly listening to and helping refugees adjust to their new environment and find employment relevant to their backgrounds without a deficit assumption, he could have found his own way to get a decent job that he wanted for himself and his family.

Reading about Franklin’s five-year struggle to secure meaningful employment in Australia really hit home for me. Franklin’s situation illustrates how misjudgments at crucial intervention points can lead to prolonged hardship.

The first and perhaps most crucial intervention point should have been right at the beginning, when Franklin’s case manager assumed he lacked English proficiency and directed him to enroll in English courses. This was a critical error. Instead, the case manager should have thoroughly assessed Franklin’s English skills and professional qualifications. Given his experience as an English teacher and interpreter, a more appropriate course of action would have been to guide him toward pathways that recognized his skills, such as a qualification bridging program or direct entry into the workforce.

On a broader level, there is a clear need for policy interventions to address these systemic issues. I believe the Australian government should develop policies that streamline the recognition of foreign qualifications, particularly for skilled migrants like Franklin. This would prevent the unnecessary repetition of qualifications and help migrants integrate more effectively into the labor market. By tackling these issues at both the individual and policy levels, many talented individuals like Franklin could avoid years of frustration and instead contribute fully to their new communities. Accounts from migrants like Franklin and others in this research highlight the need for us, as a society, to do better in ensuring that people in similar situations can thrive, not just survive.

Franklin’s trajectory during his time from fleeing South Sudan to now is a whole combination of things that he didn’t need to do if the country was more accepting and acknowledged of his qualifications and English status. When he arrives in Australia, he’s tasked to apply for English Language courses, his case manager assumes that his English proficiency is not up to par for employment. Franklin doesn’t last long in the class due to his teacher advised him to withdraw because his English is too advanced for the course. But Franklin still needs an assessment of his experiences; his qualifications. He enrolls in a computer course, but this also doesn’t help with his career. When Franklin goes to start working in teaching again, an ode to what he did in South Sudan with years of experience, his qualifications are not acknowledged in Australia and he has to gain an Australian degree to teach.

There are a lot of things that could have been done to change what happened to Franklin. What if his previous teaching experiences and qualifications were accepted in Australia, and Franklin was able to teach immediately after he came to Australia? What if his experience and evidence of English proficiency was not assumed to be ‘poor’, and he didn’t have to enroll in a computing course just to have some sort of experience assessment through the AMEP? What if there were paid volunteering opportunities through the church for Franklin to use while he was working toward his Australian degrees?

It’s of course pointless to speculate what might have been but you are asking the right questions. One of the real frustrations is that these problems are not new, as one of the speakers during our book launch pointed out. Professor Lucy Taksa reminded us that migrant un- and underemployment has been a feature of Australian society since the beginning of non-British migration in the middle of the 20th century.

Franklin’s story is both insightful and frustrating to read at the same time. Frustrating in a sense that despite his drive, exerience, prior knowledge, and qualifications from abroad, he must still jump through hoops to be compliant and/or qualified to pursue his dreams of becoming a teacher in Australia. In regards to points of intervention, some key events come to mind:

1. At the beginning, a request to be reevaluated on his strong English proficiency rather than being enrolled into an AMEP college without good pathway choices could have helped with his career trajectory. A more thorough evaluation and interview, and perhaps some pathway counselling, could have gone a long way with starting Franklin on the right foot.

2. A better system of overseas qualification recognition would also get Franklin onto the right pathway faster instead of having to study the same course from stratch in Australia.

3. Better financial support or scholarships to assist migrants in pursuing new qualifications (required by point 2 above) to avoid a vicious cycle of being underemployed/unemployed and needing funds to meet basic needs for an individual and family.

I am sure the points above have their own challenges and limitations from an institutional and governmental perspective.

Thanks, Chris! These are 3 excellent points. The frustration with Franklin’s story really lies in the fact that, once the beginning was derailed, a certain path dependency set in …

I have a deep empathy with Franklin regarding finding work in Australia, especially teaching jobs. As far as I know, English was not an official language in South Sudan before 2011, which suggests that, when he came to Australia, he could be recognized as a migrant from a non English-speaking country. Therefore, people like him were assumed to lack English language proficiency to become an English teacher there. I can tell that I experience the same situation as Franklin where all of my qualifications and previous experiences gained in Vietnam tend to be denied when applying for a teaching position in Australia.

When I went over his trajectory again, I noticed something that could have been done differently, irrespective of political and historical context. If only Franklin had received transition support from the government or agencies who had selected him for resettlement. There should have been more career orientations so that he could prepare himself with a better understanding of the Australian labor market, particularly the English teaching sector. Speaking of the three main barriers to finding a job identified in the required reading, I believe that the linguistic proficiency could have been proven more strongly via some English standardised tests. If so, his English proficiency had not been underestimated by his case manager. Besides, if his teaching qualification was one of the internationally recognised ones such as TESOL or CELTA, it could pave the way for him to seek more opportunities in the Australian job market.

Good point about seeking standardized certification!

There is a lot I wish to say about Franklin’s trajectory but there was one possible intervention point that stood out the most. It was the beginning, how it all started. In my opinion, assigning someone to an English course just for not being a native English speaker without any assessment to back it up is very unreasonable and a little rude. I think the first thing that should have been done, not just for Franklin but for everyone else in his shoes, is to organize an assessment to judge the English proficiency level.

I myself am not a native English speaker, English is my second language. And, in my generation we have a lot of opportunities to communicate with people all around the world without seeing each other. I also communicated with a lot of people from various countries on numerous platforms through the internet. Surprisingly, many native and non-native English speakers alike thought I am a native English speaker and were stunned when they found that English is actually my second language and not my first.

Since I can relate with Franklin to a certain extent, I can see what he could have done for himself. Since the case manager misunderstood, he could have tried to communicate with him again to clear up the misunderstanding. I know it is not as easy as it sounds like, but that is what I would have done. If the case manager said there is nothing he could do, then I would have requested arranging a formal examination of the highest level of language proficiency. As sad as it is, the truth is this world runs on certificates. A English proficiency certificate would have made his life so much easier. It would not have solved everything but it would have been a positive step towards his ultimate goal.

Thanks, Tasnim! Good that you can advocate for yourself – a very important skill in today’s world. Unfortunately, particularly in early settlement, migrants often can feel reluctant to question authority.

Franklin’s story exposes the incompetency of the migrant settling initiatives of the government. The assumed English-deficit; discounted degrees and professional experience; lack of accurate guidance and career counselling to bridge the vocational gap; financial handicap- divided between pursuing a career and supporting his family, where clearly supporting one’s family wins. He’s a victim of the humanitarian crisis existent in the world today and has not truly experienced freedom despite living in a country free of war and conflicts. In Franklin’s words, this is essentially an experience of being ‘handcuffed’.

Franklin could have escaped this experience of frustration and self-doubt if some feasible and commonsensical measures were in place. For instance, the case manager could have conducted a professional English proficiency/placement test and not blindly assign him to an AMEP program. Secondly, the English language centre could have given him proper course counselling and guided him in the direction of a teaching career considering his qualifications instead of leaving him to figure it all out on his own. This whole process of migrant assessment and evaluation could use a career counsellor and along with rejection or demotion, a suggested career pathway and ways of facilitating this should be clearly suggested to the candidate. Thirdly, considerable financial support for his family would have helped immensely so he could completely focus on his studies and be successful in building a meaningful career.

As a migrant, I did not face similar struggles as Franklin, but the authors’ work has truly enlightened me by showing that absence of valuable social capital and perception-induced linguistic and human capital deficit can prove to be an unsurmountable setback for a settling migrant.

Thanks for the clear, readable and engaged summary!

The Franklin’s trajectory in Australia makes me overwhelmed with anxiety of finding jobs and settlement here as an international student. Although he had proper credentials and professional teaching experience in his country Sudan and Egypt, he couldn’t get a decent job due to the assumption of migrants’ human resource deficits, such as low English-language proficiency, inferior qualifications. In this regard, in my view, this stereotype is a common phenomenon and kind of discrimination, especially for humanitarian migrants.

In terms of some key intervention points for him, I would say that at first, it was misevaluation of his English proficiency by his refugee case manager. Secondly, there was lack of the guidance and support to bridge the gap between his previous credentials and new requirements under the Australian system. Finally, Franklin’s financial burden and family responsibilities as a breadwinner.

However, by sorting out these barriers step by step, he could get closer to get the meaningful work and successful settlement in Australia.

Sorry to hear that Franklin’s story has caused you anxiety. Fortunately, you are good at identifying intervention points and hopefully can get help before anything spirals out of control and develops into a major crisis, as happened to Franklin.

Dear Ingrid, I am interested in this story; thank you for allowing me to read it. Based on what I understand, in Franklin’s case, there were crucial times when early help could have made a big difference in his future. Having complete language support at work might have helped him get through the complex parts of his job. He could have communicated better and fit in better with others if he had gotten personalized language lessons and guidance from coworkers who knew how hard it is to work in a second language.

Also, early on in settling in, job counselling could have helped him find skills that could be used in other situations and paths that would have fit his qualifications. Community groups and employment services could have been beneficial in giving him individualized help, making him less reliant on unofficial networks that led to less safe job possibilities. Focusing on these measures could have made Franklin’s trip one of excellent security and growth, showing the power of focused help at the right time.

“Focused help at the right time” is key, as you say.

Reflecting on Franklins experience reveals a number of important area that enhanced his chances of finding work as well as settling in Australia.

Firstly, before making nay kind of assumptions about his language skills, it’s better to perform individual assessment of his qualification. This evaluation has better connected to his educational and personal needs with the right resources. A personalised counselling program might have been very helpful for Franklin’s in terms of current skills. Career counsellors with experience in migrant could offer guidance on procedures for recognising qualification.

Rather than enrolling Franklins’s in general English classes schools ought to have provided focused courses that link international qualification with Australian requirements. Strong support networks, social services and program may have also linked Franklin’s to important resources, helped with his job, provided financial aid for his studies. Lastly, receiving therapy that really affects the mental health of unemployment. It essential to controlling the stress and this kind of stress he was experiencing in his job.

At which point exactly do you think mental health support might have been useful?

I believe every foreigner coming to Australia, whether for study or work, can relate to Franklin’s story and the issues highlighted in the article. As a newcomer in Sydney, I understand the challenges of adapting to a new language and culture. Despite having extensive international experience and familiarity with English in various settings, it is still disheartening to see my previous qualifications and work experience overlooked and considered irrelevant and I need to start over from the beginning. Fortunately, I still have chances to find a job where employers value my actual skills and experiences.

The current standard process in Australia often places migrants into AMEP courses regardless of their English proficiency. This one-size-fits-all approach fails to recognize those who are already fluent or whose roles do not require advanced language skills. Instead, a more tailored assessment could evaluate whether migrants’ previous work experience and qualifications can be directly applied in the Australian job market. This would better align with their career goals and help address Australia’s skill shortages more effectively.

Overall, I do understand every policy is public based on thoughtful decisions of the authorities. However, it would be better if Australia could focus on recognizing and valuing overseas qualifications and professional experiences to better support migrants and make full use of their skills in the workforce.

Not sure I share your optimism that every public policy is based on thoughtful decisions …

The story of Franklin, as many other experiences in the articles, reflects a troubling reality for many immigrants in Australia today. It’s a well-known issue that to work in Australia, immigrants often need specific certifications, regardless of their existing degrees or experience from abroad. Franklin’s frustration is completely understandable. Despite his qualifications and experience, he struggled to find a job simply because he did not have any Australian certification. What makes his story even more heartbreaking is the personal cost he faced with his family and his loss.

Government and community organizations are great options for seeking orientation, some employers (as in my case) can give some good advice, networking building, or even expats who have experienced the same difficulties so they could guide you in the process.

I’ve faced similar challenges myself. When I started job hunting in Australia, I encountered barriers due to the lack of local qualifications. For example, many international schools require additional certifications beyond a bachelor’s degree. To meet these requirements, I had to complete a CELTA course. Thankfully, this qualification has now enabled me to teach here, but the experience underscores the significant obstacles immigrants face in their professional journeys.

Glad you’ve been able to establish yourself!

After reading relatable life journey of Franklin from Sudan to Australia for better life opportunity, several intervention points are emerged which can be considered systemic barriers faced by maximum immigrants from starting journey to settled down phase.Firstly,English assessments test that is required from Australia government has misleads him towards AMEP and even if having a capability to speak prompt English he has to take English proficiency test hoping to find and better job and language barriers which is relatable to many migrants as we have to go through English proficiency test in every stage to prove ourselves that we can speak English as Australian.

additionally,Franklin’s Sudanese qualification weren’t recognised, which significantly hinders his career prospects and lack of proper guidance over job opportunities in Australia creates sadness and dilemmas in his life like maximum workers having now , so basically enhanced career counselling and support system to migrants needs could have provided clearer pathways for career development. Similarly, Franklin’s low financial status and family situation have forced him to get into low skills employment jobs which has wested his time and energy .Heavy university fees and high living expenses are the barriers which result low performance and mental himderances among the students and to deal which them they basically try the horrible pathways that mislead them from their goal of life. To tackle the all the problems I think programs that offers financial assistance,part time study options and skills related training could help migrants and refugees to balance their education and financial needs effectively. People should understand language is not only about speaking , Australian culture believes if you can’t speak standard English you are uneducated and belong to low skilled job, which should be changed s that there will be better working culture for all the immigrants from the world.

Franklin’s experience made me realize that if there is external help, his situation may have many opportunities for change. Although Franklin has academic qualifications and work experience in his own country, it is difficult for him to continue his original job in Australia. I believe that experienced teachers like him do not need to spend a lot of time retraining but only need to provide relevant training guidance and evaluation to help them find a suitable job. This will not only help Franklin but also alleviate the problem of vacancies in teaching positions in Australian schools. Therefore, I think the key to solving this problem is that education and vocational certification agencies need to establish a more complete system to help immigrants convert their international qualifications and provide clear guidance to help them fill the qualification gap.

Thanks for mentioning the teacher shortage – which makes Franklin’s experience even more damaging, as you point out.

As an international student who is considering migration, Franklin’s story really hits home for me. It underscores the difficulties that even highly educated migrants can face when trying to find employment, especially when their language proficiency is unfairly judged. Franklin’s experience highlights how crucial it is to have timely and effective support throughout the entire settlement process. If a comprehensive orientation program had been provided to Franklin before his arrival, it could have made a significant difference. Such a program should have included professional and specific language training, and detailed information about the Australian job market. Upon his arrival, a targeted support system could have accurately assessed his English skills and qualifications, ensuring he was placed in a language or job training program. Additionally, settlement support agencies need to play a more active role in helping migrants like Franklin get their foreign qualifications recognized and guide them through the process of obtaining local credentials. Employment support services should be expanded to offer practical help with resume writing, interview preparation, and job applications. Furthermore, even after securing employment, ongoing mental health support and professional networking opportunities would have significantly contributed to the long-term success in integrating into Australian society.

Good suggestions and good luck with your migration plans!

Upon reading Franklin’s story, I realised that the refugees and other migrants often have to face so many challenges to rebuild their lives in a new country. Despite Franklin’s substantial qualifications and experience, he encountered systemic barriers that were rooted in assumptions about his English proficiency, a lack of recognition for his foreign qualifications, and an absence of meaningful career guidance.

Critical intervention points stand out throughout his journey. To begin with, upon Franklin’s arrival, it was crucial to have conducted a thorough evaluation of his English proficiency and qualifications. This evaluation would have prevented his placement in the AMEP program and guided him toward opportunities that aligned with his skills and career goals. Franklin’s case manager missed an essential chance to offer personalized career guidance that matched his aspirations and existing abilities. Therefore, I believe that career counselling could have connected Franklin with relevant training or mentorship opportunities in the education sector or related fields, thereby preventing him from drifting into unrelated, low-skilled jobs. Secondly, the recognition of Franklin’s teaching qualifications from Sudan should have been systematically addressed early in the resettlement process. If his credentials were not directly transferable to the Australian context, he should have been given clear guidance on obtaining local certification, whether through bridging courses or examinations. In conclusion, the story of Franklin emphasizes the importance of implementing more personalized and supportive integration processes that acknowledge the skills and qualifications that migrants possess.

Reflecting on Franklin’s trajectory, it’s evident that systemic barriers and qualification mismatches significantly hindered his career advancement. Despite his impressive background, Franklin faced a challenging and prolonged adjustment period due to the undervaluation of his qualifications and a rigid job market. His situation underscores the broader issue of underemployment among migrants, where their skills and experience are often overlooked or unrecognized.

To achieve a better outcome, several interventions could have been beneficial. Firstly, immediate support from migration agencies and employers in recognizing foreign qualifications would have provided Franklin with a clearer path to suitable employment. Streamlining qualification recognition processes, as advocated by Ingrid, would have prevented the mismatch between Franklin’s credentials and available job roles. Implementing a more integrated approach between visa and professional qualification processes could have lessened some of these barriers.

Additionally, fostering more empathetic and inclusive attitudes from employers and colleagues could have eased Franklin’s transition. Understanding and support from these key stakeholders, combined with effective social networking opportunities, might have helped Franklin find a role that better matched his skills and aspirations sooner. Integrating these strategies could create a more equitable labor market for migrants, ensuring that their talents are fully utilized and valued.

Although migration is common, there are still some challenges for immigrants. For example, the immigration process in Australia has to assess language proficiency and qualifications carefully and fairly. However, this was not the case of Franklin.

The most tragic point about Franklin’s migration was that his refugee coordinator misunderstood his English proficiency. Even though he has a teaching license in English in his country and enough experience, he was assigned to English course as a refugee program at first. I think this incident negatively affected his future career as “Life in a new language” pointed out it. Furthermore, the fact that assessment process is different between states and territories is so uneven and confusing. I think it is necessary that the structure is revised in order to assess immigrants’ abilities appropriately when they arrive in Australia.

In summary, the government should revise the way to evaluate immigrants’ abilities, knowledge and qualifications as soon as possible. If their skills are recognized correctly in the immigration process, their talent would enrich not only their lives but also Australian society, which was as the author mentioned.

Thanks, MI. “The government” is of course a very big and abstract entity – can you think of more concrete actors who might have helped Franklin?

Sorry for my unclear comment.

I am not very familiar with its procedure, but I think the staff who directly talk to immigrants like Franklin’s refugee coordinator have to pay attention to assess immigrants’ abilities because the assessment has a huge impact on their new life in Australia. In order to do that, clear and fair criteria should be established by immigration authorities.

In addition to that, in the case that immigrants struggle to get their ideal job after settling in, I hope local government and community service organizations help them access effective information and gain opportunities.

Franklin had completed high school and teacher training in South Sudan in English. But when he arrived in Australia, his qualifications weren’t accepted, and no one properly checked his English skills—they just assumed that they were not too good. He followed the advice given by his case manager and teachers but ended up in a course that didn’t match his skills and this didn’t help him understand how to find a job.

Because his qualifications weren’t recognized, he couldn’t get a job in his field. He also couldn’t afford to study full-time for another four years to get a recognized qualification. So, he ended up working in an abattoir, which was not fulfilling but was necessary to support his family. He was given a low-skilled job because his qualifications were misunderstood and he didn’t get enough career advice.

To help migrants like Franklin, it would be helpful to have better ways to recognize foreign qualifications, provide targeted career counseling, and language skills, language training, and offer access to professional networks. These steps could have greatly improved their job prospects and helped them better integrate into the new community.

Thanks for the summary, Liz! Can you identify concrete intervention points? Who could have done what when?

Before talking about Franklin, I want to mention how listening to the podcasts makes me think of the White Australia Policy of much of the twentieth century and how it casts a long shadow. This policy was designed to prevent immigration by non-whites (especially Asians), The final nail on this policy only occurred in 1975 with the introduction of the Racial Discrimination Act. When combined with other immigration policies that favoured English speaking (British) migrants much of Australia was mono-cultural, mono-lingual and white. Most of the exceptions to this were inner city communities in Melbourne and Sydney.

As a consequence I can imagine many managers would either no or limited experience working in a multicultural and/or multi-racial environment could put the employment of non-whites in the too hard basket at best or refuse to hire on a racist basis at worst.

Now because Franklin and his compatriots are arriving on a humanitarian visa, I assume they were directed to this particular location by the government. In this case the groundwork for incorporating this cohort should have been laid before/as they arrived. This should have included meeting with the major employers in the region. They should have been provided the opportunity for support and training in working with and employing people with CALD and refugee backgrounds. There should have also been outreach by/ provision of AMEP and SEE (Skills for Education and Employment) programs. Also, in Australia, there are a variety of programs to subsidise the wages of marginalised groups for those that employ them. There was the opportunity to promote and/or provide such programs. Even if these programs were only provided to major employers it would have provided momentum for employment in the wider community.

There is also the issue of recognition of prior learning/experience to those wishing to follow a profession or skilled trade. This can often be a fraught process for a native speaker/native Australian, let alone a refugee who may have had to relocate without access to documentation to support their claim. Not only this but a number of private programs will charge an upfront and non-refundable fee for the assessment process. These fees can be in the order of thousands of dollars and beyond the reach of those on a tight budget. These processes should be made more accessible and affordable and better publicised to refugee and migrant communities .

Thanks for connecting macro and micro migration policies so well! Like the idea of the job fair with employers in the region.

Reflecting on the case study of Franklin in chapter 3 of the book Language on the Move, I believe it would’ve been much better if the Australian government intercepted the process during his arrival to Australia and when he was struggling to maintain his studies.

There is a social barrier that prevented Franklin from achieving a successful migration, causing a human capital deficit. The Australian government could have assessed Franklin’s English and employment skills more accurately by using existing systems in other immigration programs (such as skill assessments in the skilled migration streams). There’s also a disconnect between different government levels in refugee employment, as there seems to be no assistance from the local government to help Franklin obtain a job.

As humanitarian visa holders have permanent resident status in Australia, I am wondering if Franklin could have had access to welfare programs like Centrelink and HECS-HELP when he struggled to pay his bills and maintain his studies – or had the knowledge to apply for them at all. Again, the local government, and by extension the local community, could have helped him assimilate better and let him know about these programs and benefits that a permanent resident can access.

Franklin did have access to welfare but that is of course very little money for someone in the prime of his life with many commitments; also, the point for Franklin was that he wanted to work and be independent

The book is called Life in a New Language, btw 🙂

Sorry about the confusion about the book title!

From my experience, getting a job in Australia does require a lot of effort to make yourself employable, find new connections, and grow your network. This is really hard for anyone with a ‘language barrier’ (that was socially established), let alone in a regional town! It seems that the local governments simply ‘forget’ about his existence and let Franklin figure it out himself – a bit of local help could have made so much difference!