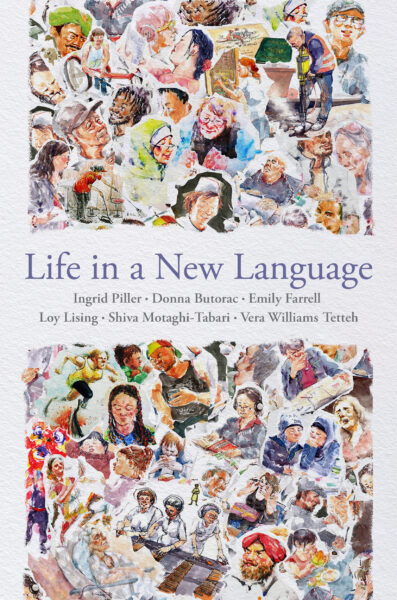

This episode of the Language on the Move Podcast is Part 3 of our new series devoted to Life in a New Language. Life in a New Language is a new book just out from Oxford University Press. It is a project of Language on the Move scholarly sisterhood and has been co-authored by Ingrid Piller, Donna Butorac, Emily Farrell, Loy Lising, Shiva Motaghi Tabari, and Vera Williams Tetteh.

Cover art by Sadami Konchi

International migration is at an all-time high as ever more people move across national borders for work or study, in search of refuge or adventure. Regardless of their motivations and whether they intend their moves to be temporary or permanent, all transnational migrants face the challenge of re-building their lives in a different cultural and linguistic context, far away from family and friends, and the everyday routines of their previous lives. Established populations in destination countries may treat migrants with benign neglect at best and outright hostility at worst.

How then do migrants make a new life?

To answer that question, Life in a New Language examines the language learning and settlement experiences of 130 migrants to Australia from 34 different countries in Africa, Asia, Europe, and Latin America over a period of 20 years. Reusing data shared from six separate sociolinguistic ethnographies, the book illuminates participants’ lived experience of learning and communicating in a new language, finding work, and doing family. Additionally, participants’ experiences with racism and identity making in a new context are explored. The research uncovers significant hardship but also migrants’ courage and resilience. The book has implications for language service provision, migration policy, open science, and social justice movements.

Today, Brynn chats with Dr. Vera Williams Tetteh, with a focus on the experiences of African migrants.

Use promo code AAFLYG6 for a discount when you purchase from Oxford University Press.

Advance praise

“This volume breaks new ground by focusing on Doings: a group of diverse researchers collaboratively doing close listening and looking over 20 years, as adult immigrants to Australia engage in doing life, things, words, family, and work in a new language. The result is not only new understandings of the participants’ self-making, but also the making of a new research trajectory that focuses not simply on the learning of a language, but on humanity doing life in language.” (Ofelia García, The Graduate Center, City University of New York)

“This is a moving book that represents the voices of migrants on their challenges and successes across different kinds of boundaries. It embodies impersonal structural and geopolitical pressures as negotiated in the dreams and aspirations of migrants. The authors share findings from decades-long separate research projects to develop richer insights, as a model for data sharing and ethical research.” (Suresh Canagarajah, Pennsylvania State University)

Transcript (by Brynn Quick, added 04/07/2024)

Brynn:

Welcome to the Language on the Move podcast, a channel on the New Books Network!

My name is Brynn Quick, and I’m a PhD candidate at Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia.

Today’s episode is part of a series devoted to Life in a New Language.

Life in a New Language is a new book just out from Oxford University Press. It’s co-authored by Ingrid Piller, Donna Butorac, Emily Farrell, Loy Lising, Shiva Motaghi Tabari, and Vera Williams Tetteh. In this series, I’ll chat to each of the co-authors about their perspective.

Life in a New Language examines the language learning and settlement experiences of 130 migrants to Australia from 34 different countries in Africa, Asia, Europe, and Latin America over a period of 20 years. Reusing data shared from six separate sociolinguistic ethnographies, the book illuminates participants’ lived experience of learning and communicating in a new language, finding work, and doing family. Additionally, participants’ experiences with racism and identity making in a new context are explored. The research uncovers significant hardship but also migrants’ courage and resilience. The book has implications for language service provision, migration policy, open science, and social justice movements.

My guest today is Dr. Vera Williams Tetteh.

Vera is an Honorary Research Fellow in the Department of Linguistics and a fellow member of the Language on the Move research team. Her research interests are in second language learning and teaching, intercultural communication, World Englishes, language and migration, and adult migrant language experiences.

Vera completed her PhD with a thesis exploring the language learning and settlement experiences of African migrants in Australia. The thesis examined the interplay between pre-migration language learning and education experiences, and post-migration settlement outcomes in Australia, and the thesis was shortlisted for the 2018 Joshua A. Fishman Award for an outstanding dissertation in the sociology of language and was the runner up for the 2016 Michael Clyne Award from the Australian Linguistic Society.

In 2018, Vera received the Department of Linguistics’ Chitra Fernando Fellowship for Early Career researchers, and she is now working on a collaborative study focusing on oracy-based multilingualism in sub-Saharan African communities in Australia. She also engages in interdisciplinary research with colleagues in Sociology, Business, and Marketing.

Welcome to the show, Vera. We’re really excited to talk to you today.

Dr Williams Tetteh: Thank you, Brynn, for that introduction, and good to be here.

Brynn: To get us started, can you tell us a bit about yourself and how you and your colleagues got the idea for Life in a New Language?

Dr Williams Tetteh: So I’m Vera Nah of Osua Williams Tetteh, an African-Australian woman born and raised in Ghana. I’m from the Ga-Adangbe ethnic group in Ghana. My mother tongue is Ga, and growing up, my family moved from my hometown in Accra to Koforidua where Twi, or Akan, is spoken. So that’s where I learned to speak Twi. And Twi is spelled T-W-I, not T-W-E, as I found in a library recently. I completed my university education in Australia at Macquarie University from a foundation that goes way back to Ghana.

I attended a Aburi Girls Secondary School in the Akuapem Mountains of Ghana. This is the boarding school where I studied for my O-level and A-level exams, and where for seven years, my classmates and I were nurtured, and we blossomed into skilled women that we are today and were spread across our various parts of the global world. Most of my classmates after school went to university straight away.

My trajectory took a different and not so linear direction. I didn’t make the grades for a straight entry to university, so I had to get a job, which I did. I was working at the State Insurance Corporation of Ghana. That is where one of my colleagues introduced me to Benjamin, my husband, who was living in Australia. So, I joined him on the Family Reunion Visa. All this happened in the early 1990s.

In Australia, while juggling a new family life in a new country, I also found my first job as a shop assistant in Franklins. And I worked there in different locations for 10 years. And in the latter part of that 10-year period, I was also studying at Macquarie University, completing my honors degree with Dr. Verna Rieschild as my supervisor.

Verna identified that it would be good to go and shift directions into academia rather than working in the supermarket after my studies. So, Verna gave me my first tutoring role in the Department of Linguistics at Macquarie University. And with my honours degree, I earned a first-class honours.

And with Verna’s encouragement, once again, I applied for the scholarship to do the PhD in Linguistics, which I did and completed under the supervision of Distinguished Professor Ingrid Piller and Dr. Kimie Takahashi.

Now to the second part of the question, how did I get the idea for Life in a New Language, or rather, how did I come to be a co-author of Life in a New Language? After my PhD, I was fortunate to be one of the two postdocs working with Ingrid on her ARC-funded project, looking at everyday intercultural communication.

So, we defined everyday intercultural communication as interaction between people from different linguistic backgrounds and with different levels of proficiency in English in interaction. And such interactions obviously happen a lot in Sydney. And we were hoping with that study to improve institutional communication through findings from our research.

So that’s what we were working on with Ingrid. So, the interesting thing is that my colleague Shiva, Dr. Shiva Motaghi Tabari and I had completed PhDs working with migrants within Persian and African communities respectively under Ingrid’s supervision. And we had gathered our rich data, which was specific to our communities.

And we were focusing also on their settlements and their communications. So, we already had the rich data waiting to be used. And given the current, you know, climate of data sharing and the natural progression under Ingrid’s expert direction, of course we were able to pull all our ethnographic data together, analyse them and get them all into one volume.

Brynn: That’s what’s so interesting about Life in a New Language, is this reuse of ethnographic data. Can you tell us about your particular research that was then incorporated into this reuse of all of this ethnographic data? What did your particular research look at?

Dr Williams Tetteh: So, my research was with African migrants and their settlement experiences in Australia. So, I looked at their pre-migration language learning experiences, opportunities as well, and the post-migration experiences. I realised in the beginning when I first started researching, doing background reading for my work that not much was understood about African migrants, and we were all pulled together under one deficit lens that saw us as not able to settle or finding difficulties.

And so, my study comes with looking and sharing how different people with different experiences of having English or not having English, do life in a new place with English. In my study, I used four typologies to look at this situation. The first group was migrants from Anglophone African backgrounds who have completed secondary school or above, and English would have been their language of education.

And group two was people from non-Anglophone African countries who would have completed secondary school or education or above in a different language like French or Arabic. And then group three, migrants from Anglophone African countries who have had no schooling but have street English or have learned and used English. And then the last group was people from non-Anglophone African backgrounds who have had no schooling, did not have English as well.

Because remember, in Africa, most of us study in a language other than our mother tongue, the formal language is English or Arabic or the language of the former colonial country that colonised our states. So having those four groups made it easier to see some of their experiences and bring out all these things that would otherwise would have been hidden if we put everything, everyone together. So, looking at people from group one who already had skills and studied in English, they expected that, you know, they would be able to use their English, their skills.

And after all, Australia is an English-speaking country and they’ll be able to slot in. But that didn’t happen for them that week at all. So, there were some challenges.

And what was interesting is that the people were prepared to continue with their studies. They got more Masters and other studies at tertiary level to skill themselves and still they were struggling to get jobs. With group two, people who studied in a different language, a language other than English, they felt that they needed to learn English to be able to use their skills as well.

The people in my study at that time were still learning English and hoping that afterwards they will be able to get jobs and work in Australia. The next group is group three. So, group three was mainly people who did not have schooling and had some English as well.

And you find that most of the people in this group were women. These people were in classes to learn, and sometimes there was a mismatch with the English language. These people are multilingual. Some of them have five, six languages that they have learned already. The only thing is that these languages are oral based languages, so that made it a bit difficult when you sat in front of the classroom and a computer. So, there’s a lot of assumption there.

And so, they struggled as well. One of the participants said that, you know, they put us, because we’re speaking, you know, because they’re oral beings, they speak English, you put in class with people who have degrees and so on and so forth. And then in there you’re shown that, you know, you do not have what is required.

So that was challenging for them. And then we have people from the last group who were learning English as well as doing things in English for the first time. And that was in itself quite, quite difficult as they found.

Language learning experiences and settlement for the participants were quite different for the four groups. And I think that’s what my research shows so clearly and interestingly that hasn’t been seen previously. And that’s what it brings to Life in a New Language.

Brynn: It sounds like because you were able to distinguish these four very different groups, you probably saw their employment trajectories or sort of what they hoped to be able to do in Australia in terms of employment as quite different. That would be my guess, but maybe not. Can you tell us a bit more about what the four groups wanted to do with employment and sort of the realities that they faced in Australia in terms of employment?

Dr Williams Tetteh: So in terms of employment, most of the participants in group one, when I found them, most of them were still studying, looking for skilled jobs. Some of them, their certificates were not recognised. Some of them had started work in low skill areas.

Some of them were doing process work while studying and trying to get better grades or better qualifications so that they can get better jobs. So yes, most people were in that situation doing that, to qualify and to be able to find a good job. So that’s group one.

People are aspiring to go better and do jobs because some have skills and they work in the countries of origin and they have English skills and they believe that they should be able to get jobs, but it didn’t pan out like that for them. Those from French and Arabic, people who had studied in French and in Arabic, well, some of them were studying English knowing that when they finished their English, they will be able to get jobs. Some were in university, some were doing nursing, and they believed.

So, the difference is that they believe that they will be able to get a job and it’s the language that is hindering them from going forward to get jobs. Group three was quite interesting because some of the women turned to ethnic jobs. Women in particular had all the ethnic businesses that they had started hair-braiding.

One in particular had gone to TAFE to get her certification so that she started a hair-braiding business with her husband. People have started big shops because there’s the need for that in the community. For some of the participants, their hairdressing shop or hair-braiding shop or African shop also doubled as a community place where people who newly arrived in the country would go to find things and go informally to be pointed to where to go, in which direction to get help, that kind of thing.

So, it’s interesting. Group 3 brought skills and expertise in business into Australia and they’re thriving in that aspect. And then Group 4 were still looking for jobs and still, some of them were still learning the language.

And it was quite challenging for Group 4, having no English and also having no education and trying to make sense of it all was quite challenging. Most of them were women as well. They were doing as much as they could, juggling things at home, going to classes, learning from their children and having hope for some that even if they don’t make it, the investment in their children will make a difference for their lives.

So, it was quite interesting, all these different ways people approached life in the different groups. One interesting thing to note though, it was normal, well not normal I’d say, it was quite common to have a man in Group 1 and his wife in Group 3 or Group 1 and the wife in Group 4 because of pre-migration gender expectations. Mostly men had gone to school and were higher in the older cohort. So then in Australia, you’d find that when the dynamics change and the men are struggling to get jobs and the women are able to get some process work and things, you find that the home is changing, and women become the breadwinner and the man is still doing his certification and going through. So that kind of changed things a bit for some of the participants.

Brynn: That’s such a fascinating dynamic. And I really thought that that particular part of the book, because that does come up in several parts in Life in a New Language, especially with your research, that part is so fascinating because I feel like that’s not something that we generally think that much about are sort of the ways that family dynamics change or relationship dynamics change when people do have to do this move to a new place. And then you throw in the language difference on top of it.

And that makes for a really different settlement experience for people. And it sounds like these are some really difficult processes that people went through. In your opinion, based on what you saw in your research, what is something that we in Australia could do to make this settlement experience easier for new migrants?

Dr Williams Tetteh: That’s a tough question and a good one too. I think I’ll go back to what we do at Language on the Move. Our everyday experiences and bringing this book together is because we embrace people that come in.

So, you have a team of people. Some people have been there already. I’ve worked with Ingrid since 2007. So, we have, let’s say, senior team members, and then we have junior team members, people coming in. And we see us as a team. So, when you come in, we embrace you and we help you and we show you what to do.

So, on that micro scale, that’s what we do. I think if we open that up to the broader macro domain, this is a country where people are coming in. There are people here already. So, what do we do? We embrace them, we buddy with them, we show them around. And it’s not a one direction way of doing things.

We also learn from the newcomers because they’re not coming as a blank person that came with nothing. They have already brought things with them that we don’t know anything about. So, I think we need a deeper understanding of the push and the pull factors that make people come here. What are they here for? What brings them here? Like they venture into the unknown, even hostile places to begin life.

And for some, it’s going to be a life in a language that they’ve never heard before, never spoken before. But they’re here and they’re human beings. And we’re all migrants. I mean, this place belongs to the indigenous custodians and owners of the land, past, present and future. We all happen to be – our origin is from somewhere else. And so, some people have taken the lead and come here.

And newcomers come in, we can embrace them, we can look at what they bring, the positives, not just the challenges and we don’t want them. And especially when they look a certain way, then we find ways and means of putting barriers instead of helping them to move along. People who come with multiple languages maybe have oral-based knowledge in these languages and may not have the literacy skills, but we can tap into what they have and then help them rather than seeing them as deficits in English.

When a monolingual English person is teaching someone who is multilingual and has learned so many languages, what can we learn from how they learn their languages and do it their way rather than fitting them into what we feel they should go and do and then erase all the positives they bring in linguistic resources and see them as deficits because they cannot have English. And in doing so, then we equate English with knowledge and wisdom, and then we perpetuate that kind of myth, which is not the case. It’s really a challenge.

And at this time, the one persistent issue for my community is with this English test, language test, especially when people have done their degrees here. And recently we had to write to MPs to say they have to have another look at this criteria, because people have studied in English, have done their degrees in English. And then before you register as a nurse, you need to be able to pass your IELTS test so that you are registered.

These people, before they even go into nursing as registered nurses, are working as ARNs, so they are working as nursing aides and assistants in nursing homes and doing all sorts of shifts to be able to live here and help, helping our system, helping our disabled, helping our aged. And so, for them to better themselves and go to university, some of them work full time and also put all these things together. And then they have to do this test.

People have done this test and then they will tell me that, you know, the test, I don’t think it’s about English. They tell me it’s just not about English. I’ve done this test five times. I give up. So, I’ll just work in the nursing home. I’m not saying working in the nursing home is not a good job. When people have identified that they want to further their career, and this is what we want in Australia, then of course, we need to not put barriers in there like that. Yes.

And one of them said to me, this is just making us into second class citizens because they don’t want us to be registered nurses, which is unfortunate. So, if you haven’t done your second reschooling in here, then you have to do the test to prove. And the test to them is not about English, it’s more computing.

Brynn: Yeah, there is so much we could say about the IELTS test and about English language testing. And we have so much at Language on the Move about that. And I’m sure that that will be, we’ll have more podcast episodes devoted to just that, because that’s such a huge part of the migrant settlement experience in English.

And that’s something that, you’re right, I think that we as a society need to devote more thought to and we need to rethink what we’re doing there.

Shifting gears a bit, let’s talk about how you co-authored this book, Life in a New Language, with five other people. So, there were six of you working on this book. And I want to know how complicated was that and what were the ups and the downs of the writing process? And what did you learn from writing with so many people at once?

Dr Williams Tetteh: That’s a good question. So, I have also heard about some of the challenges and interesting dynamics with co-authoring. I think for us, it was pretty straightforward.

It was straightforward because we had Ingrid in the center who knows all our work. So, Ingrid was our supervisor, my supervisor, Donna’s supervisor, Emily’s supervisor and Shiva’s supervisor. So, as I said previously, we have this data that is sitting there that Ingrid has supervised.

And also, Ingrid was Loy’s supervisor and mentor in her staff grant project. So pretty much, it’s just like this was the natural progression of the data. Ingrid has worked with all of us with our PhDs and all the ideas coming together.

So, it was good in a sense that you had the uniting factor and the supervisor, mentor, who knew our strengths and our differences as well, our challenges as well. So, putting it all together, it was just a fun thing to do. And I’d like to say that for individually, our strengths come from within our academic excellence, by the nurturing and the healthy relationship that we had.

And for us, it was not just about write your bit and that’s it. We had this lovely relationship and I think that’s very, very important. So, it was not just the writing, but it’s outside of the writing. What do we do? The unspoken characteristic is just that we do things together. Extracurricular activities, asking how each other is going, you know.

That hand holding, that pastoral care, that knowing that it’s not just about work. There’s life outside of work, some of the challenges. And having Language on the Move also as a platform, that family, you know, that nurturing place, there was no, you didn’t feel scared or worried or threatened or anything. We were just a pool of people eager and willing to learn under Ingrid’s supervision and to work together and let our strengths shine through.

For me, one of the challenges, I’d say, was working online on a shared document. I’m very old school. That is not my style at all. And so, in the beginning, I like to think through my writing, and I like to change things backwards and forwards. So, when I log in, I know that people know I’ve logged in, but I’ll download the file and I’ll work on it my way and then I’ll put the changes in.

And I think at a point Ingrid said, Vera, I saw you online, but I didn’t see what you were doing. And I said, yes, Ingrid, I’m kind of quite old school, but as we went on, I was able to be able to work a bit more online than I used to do in the beginning. So that was something I learned while writing together.

Brynn: Oh, the old shared document folder. I know what you mean. It can be really hard.

But I love that answer about making it more of a community of people who are truly working together in a non-threatening way because, you know, academia can feel scary, it can feel threatening. It is such a good example for those of us who are the more junior academics in the group. You know, I’ve got my own group chat going with some of the more junior members and I feel like we’ve been able to take what you’ve all done and learn from that.

And we’re also helping each other now, you know, like we’ll text each other and say, do you know how to format a citation in this way? You know, things like that so that you don’t feel alone and you don’t feel like you’re doing everything on your own. And then we also talk about non-academic, non-work things. And you’re right, I think it leads to a much more healthy and productive academic life that is nicer than a lot of other corners of academia.

And so, before we wrap up, can you talk to me about what you have going on with your work now? Do you have a project you’re working on? What’s next for you?

Dr Williams Tetteh: So, what’s next? I’m currently working with Dr. Thembi Dube on our Hidden Oracies Project. The project is an offshoot from my PhD research. It also stems from our advocacy work within the African community and also our collective desire, Thembi and I, as linguistics scholars in Australia, of African descent, to make visible the sideline and invisible African languages, which mostly are oral-based languages. And so naturally, they are viewed as tied to the home and to the community in their usage. But in reality, they do contribute to building social cohesiveness and healthy and resilient communities.

And these go a long way to promote economic stability for our society. So, you have people with different languages that are working in various places that, you know, broker some of the situations that are going on through their language. So, we call these languages hidden oracies because they are shared and spoken languages and their function mostly behind the scenes.

So that’s what we’re doing to promote them because they’re very important. So yeah, we’ve done a lot with that. From this project, we have contributed a chapter, Decolonizing African Migrant Languages in the Australian Market Economy. And it’s coming out next month in the edited book, Language and Decolonization, An Interdisciplinary Approach, published by Routledge.

I also have an article in preparation for inclusion in the special issue, Epistemic Disobedience for Centric Theorizing of Anti-Blackness in Australia. And this will be in the Australian Journal of Social Issues. And my paper is titled, Epistemic Disobedience, Reflections on Teaching and Researching on With and for Africans in Australia. So that’s it on the academic front. That’s my project.

My advocacy case work in Australia is ongoing with the African Youth Initiative that I work with. And also, I’m currently acting in the role of Global Director for Welfare and Mentorship for my old school, Aburi Girls, Old Girls Association. And I’m working with a team of dedicated women to give back to our alma mater and make meaningful contributions to the development of the girls in the school as they move out of school into the global world.

And I would like to end in the words of Dr. Kwegyir Aggrey of Ghana. He wrote the book titled The Eagle That Would Not Fly. He said that if you educate a man, you educate an individual. But if you educate a woman, you educate a nation. So here we are. Thank you for this interesting conversation.

Brynn: Oh, Vera, that’s such a beautiful way to end. Thank you so much for that.

And thank you to everyone for listening. If you enjoyed the show, please subscribe to our channel. Leave a five-star review on your podcast app of choice and recommend the Language on the Move Podcast and our partner, The New Books Network, to your students, colleagues and friends. Until next time.

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a