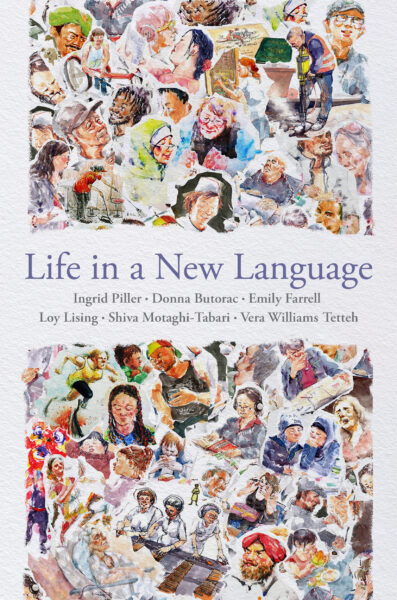

This episode of the Language on the Move Podcast is Part 4 of our new series devoted to Life in a New Language. Life in a New Language is a new book just out from Oxford University Press. It is a project of Language on the Move scholarly sisterhood and has been co-authored by Ingrid Piller, Donna Butorac, Emily Farrell, Loy Lising, Shiva Motaghi Tabari, and Vera Williams Tetteh.

Cover art by Sadami Konchi

International migration is at an all-time high as ever more people move across national borders for work or study, in search of refuge or adventure. Regardless of their motivations and whether they intend their moves to be temporary or permanent, all transnational migrants face the challenge of re-building their lives in a different cultural and linguistic context, far away from family and friends, and the everyday routines of their previous lives. Established populations in destination countries may treat migrants with benign neglect at best and outright hostility at worst.

How then do migrants make a new life?

To answer that question, Life in a New Language examines the language learning and settlement experiences of 130 migrants to Australia from 34 different countries in Africa, Asia, Europe, and Latin America over a period of 20 years. Reusing data shared from six separate sociolinguistic ethnographies, the book illuminates participants’ lived experience of learning and communicating in a new language, finding work, and doing family. Additionally, participants’ experiences with racism and identity making in a new context are explored. The research uncovers significant hardship but also migrants’ courage and resilience. The book has implications for language service provision, migration policy, open science, and social justice movements.

Today, Brynn chats with Dr. Shiva Motaghi Tabari, with a focus on parenting in migration.

Use promo code AAFLYG6 for a discount when you purchase from Oxford University Press.

Advance praise

“This volume breaks new ground by focusing on Doings: a group of diverse researchers collaboratively doing close listening and looking over 20 years, as adult immigrants to Australia engage in doing life, things, words, family, and work in a new language. The result is not only new understandings of the participants’ self-making, but also the making of a new research trajectory that focuses not simply on the learning of a language, but on humanity doing life in language.” (Ofelia García, The Graduate Center, City University of New York)

“This is a moving book that represents the voices of migrants on their challenges and successes across different kinds of boundaries. It embodies impersonal structural and geopolitical pressures as negotiated in the dreams and aspirations of migrants. The authors share findings from decades-long separate research projects to develop richer insights, as a model for data sharing and ethical research.” (Suresh Canagarajah, Pennsylvania State University)

Transcript (by Brynn Quick, added 05/07/2024)

Brynn:

Welcome to the Language on the Move podcast, a channel on the New Books Network!

My name is Brynn Quick, and I’m a PhD candidate at Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia.

Today’s episode is part of a series devoted to Life in a New Language.

Life in a New Language is a new book just out from Oxford University Press. It’s co-authored by Ingrid Piller, Donna Butorac, Emily Farrell, Loy Lising, Shiva Motaghi Tabari, and Vera Williams Tetteh. In this series, I’ll chat to each of the co-authors about their perspective.

Life in a New Language examines the language learning and settlement experiences of 130 migrants to Australia from 34 different countries in Africa, Asia, Europe, and Latin America over a period of 20 years. Reusing data shared from six separate sociolinguistic ethnographies, the book illuminates participants’ lived experience of learning and communicating in a new language, finding work, and doing family. Additionally, participants’ experiences with racism and identity making in a new context are explored. The research uncovers significant hardship but also migrants’ courage and resilience. The book has implications for language service provision, migration policy, open science, and social justice movements.

My guest today is Shiva Motaghi Tabari.

Shiva is a Post-Doctoral Research Fellow in the Department of Linguistics and a fellow member of the Language on the Move research team. Her research interests lie in second language learning and teaching, intercultural communication, language and migration, and family language policy and home language maintenance in migration contexts.

Shiva completed her PhD in Linguistics at Macquarie University on the topic of Bidirectional Language Learning in Migrant Families. The thesis examined the intersection of parental language learning with child language learning in Iranian migrants to Australia. The thesis won the Australian Linguistic Society’s 2017 Michael Clyne Award.

Shiva, welcome to the show and thank you so much for being here today.

Dr Motaghi Tabari: Thanks, Brynn. It’s great to be here.

Brynn: To get us started, can you tell us a bit about yourself and how you and your colleagues got the idea for Life in a New Language?

Dr Motaghi Tabari: Actually, my journey into the realm of applied linguistics and sociolinguistics began during my doctoral studies at Macquarie University. My research interests have always revolved around the intricate dynamics of language learning, multilingualism and intercultural communication, particularly in the context of migration. The idea for Life in a New Language actually emerged from a kind of deep-seated curiosity about the experiences of adult transnational migrants as they navigate the complexities of settling into a new linguistic and cultural environment.

The concept originated during our discussions on how language plays a critical role in the integration process for migrants. We as a group realised that there was a need for a deeper understanding of how learning a new language impacts migrants’ daily lives, their identities and their overall settlement experiences. And for my part, drawing from my background as an academic and a research fellow, coupled with the rich ethnographic data collected by myself and my esteemed colleagues, we embarked on a mission to shed light on these often-overlooked narratives, aiming to provide a comprehensive understanding of the challenges and the triumphs faced by migrants in their linguistic journeys.

And this book, in fact, is sequel to Ingrid Piller’s acclaimed Linguistic Diversity and Social Justice. It builds on years of ethnographic research with over 100 migrants from diverse backgrounds. And each of us brought unique insights from our respective fields.

And together we aim to present a holistic view of the language experiences of migrants.

Brynn: All of the co-authors came together with all of their different data and their different participants. And like you said, many of this happened over the course of many, many years. And so Life in a New Language, the book, is all about the reuse of this ethnographic data. Can you tell us about the original research project that your contribution is based on?

Dr Motaghi Tabari: My contribution is based on my PhD research, which focused on bi-directional language learning in migrant families. This research involved in-depth ethnographic work with migrant families in Australia, where I examined how both parents and children navigate the language learning process and the impact this has on their identities and daily interactions. The original research provided rich, nuanced insights into the complexities of language and migration.

In fact, I spent a good amount of time with these families, observing their everyday lives, conducting interviews and participating in their community activities. And this kind of approach allowed me to capture the multifaceted ways in which language learning intersects with their social and cultural integration. So, the insights from this research actually formed the foundation for my contributions to the book and particularly in highlighting the dynamic and reciprocal nature of language learning within migrant families.

Yeah, so it’s actually the foundation and my contribution and the contribution of other group members, my colleagues, spans over a decade of in-depth exploration of the language learning and settlement experiences of migrants to Australia.

Brynn: Your particular research, it had to do with Persian-speaking Iranian migrants. Is that correct?

Dr Motaghi Tabari: That’s correct.

Brynn: And that’s where you are originally from. So, what did that feel like for you to be talking to these migrants in this context? What did you bring from your own background that you found reflected in these migrants’ experiences?

Dr Motaghi Tabari: Oh, yes. So there are so numerous commonalities among the migrants from diverse backgrounds, including Persians, actually. This kind of research revealed fascinating insights into the ways in which migration reshapes family dynamics and relationships.

And this is something that I experienced myself when I immigrated to Australia around two decades ago. And how, kind of like many participants, the experience of settling into a new country means renegotiation of familial roles and responsibilities in light of the new social and cultural context. So, we as a group, I mean, those of us who focus on familial relationships in our research, we observed a spectrum of experiences from participants who found strength and resilience through familial bonds to those who grappled with the challenges of maintaining cohesion in the face of, you know, linguistic and cultural barriers.

Brynn: That’s so interesting because in the book that really comes through. It’s really evident that so many migrants and not just from any one particular language background, but from many language backgrounds and many different countries face that shift in family dynamics when they migrate here to Australia.

So, one of the big themes that came up in your particular contribution to the research was the role that language plays in mediating family interactions. Can you tell us more about that and what you found with your participants?

Dr Motaghi Tabari: Absolutely. So, one theme that was repeatedly coming up in the research was the pivotal role of language in mediating family interactions, as you mentioned, with language learning serving as both a catalyst for connection and a barrier to communication. That was really interesting.

And another finding related to transforming parent-child in relationships and how parents need to make language choices and how these choices may change family dynamics, like as we may know, children’s oral proficiency in everyday language can quickly become indistinguishable from that of their native-born peers. So, while children make progress in terms of fluency, parents continue to struggle with everyday language and their formal and academic English may well have been far ahead that of their children. But their oral displays were lacking as it was revealed in my research, for example.

So, this discrepancy began to undermine parent-child relationships as children began to feel linguistically superior to their parents. And the key point is that the family transformations as we were talking about and as we’ve discussed in our research do not take place in a vacuum. They are deeply shaped by the exclusions and inclusions migrant families experience in their new society.

So overall, the findings show the complex interplay between language identity and family life in the context of migration in Australia as I did my research.

Brynn: That would be so frustrating. I’m thinking as a parent myself, if I was having this almost battle in my own mind about how I communicate with my child, and those would be really complex feelings of feeling like I wasn’t good enough or I wasn’t speaking my new language well enough, and like you said, but then seeing my child become more and more and more fluent. Did any of your participants talk about their feelings related to that?

Dr Motaghi Tabari: Oh, yes, heaps actually, it was a very kind of common answer to this question, particularly for Persians who come from a background that parental authority is a thing for them, and they were worried about the upbringing of their kids on how to make language choices, because on the one hand, they wanted to advance their own language, I mean, conversational language in the new society, and on the other hand, they were worried about using the language of the society, which is English, obviously, at home as a way of practicing their own linguistic skills at home will affect their kids’ home language.

But at the same time, at some point when the kids were advancing in their conversational language, as I mentioned, they felt kind of superior to their parents. And this kind of feeling was very common among the parents who said, we really want to maintain our heritage language because we are feeling that if, for example, one of the parents said, you know, the kid keeps correcting me when I’m speaking, and I have a feeling that if she keeps doing that, then she will think that I’m a weak kind of parent and in other fields as well, in other areas as well, and I will lose my credit as a parent.

And so, it’s better to keep our heritage language as the means of communication with our kids to avoid this kind of relationship or reversal kind of roles in the family.

Brynn: That would be such a hard power dynamic to have to negotiate because, like I said, it is hard enough to be a parent and negotiate power dynamics between you and your kids, but then to throw in language, and especially if these parents also want their kids to develop English because they realize that it is important for living in Australia. I myself, when I used to teach English as a second language to adults, I would often get my adult students say to me, I won’t speak English with my kids because of that exact point that you just made, because my kids correct me, and I understand that they speak English, quote, better than I do, but I just don’t want to be corrected by my own kids, and I completely understand that.

Dr Motaghi Tabari: Absolutely, absolutely. And something that came up as well, in addition to this kind of fear, was the mixed messages or mixed advice, kind of, that the parents got from the society. Some educators would recommend them to use the home language only, and some said, oh no, just use English, because your kid needs to improve their English skills and this was something that parents seemed a bit confused in the beginning, once they arrived and once they just wanted to make language choices, what to do, what not to do.

And this was something very common as well, that it shows that there is something in the educational system that lacks probably, that needs to be worked on to support migrant families on how to deal with these kind of choices and how to maintain that kind of familial bonds at the same time have the linguistic support that they need.

Brynn: Yeah, and that makes sense that they would be getting those mixed messages because I don’t think that we, as a society, have agreed upon what is the, quote, best way to do bilingualism or multilingualism within a family. In your personal opinion, what do you think that we in Australia could do to make that transition easier for these parents, to make it easier for them to make these language choices for their own families?

Dr Motaghi Tabari: As we all know, the journey of migration is full of challenges and improving the situation for new migrants and new families actually requires a kind of multifaceted approach. Of course, there are undoubtedly avenues for improvement to facilitate smoother transition for new migrants, specifically parents and children. Well, I think one key aspect is the kind of provision of comprehensive language support services that cater to the diverse linguistic needs of migrants, which includes not only language instruction, but also access to resources for language maintenance and development within familial and community settings.

It’s really important to encourage families regarding their heritage language maintenance and providing resources. And also fostering inclusive and welcoming environments is really important. The kind of welcoming environments that celebrate linguistic and cultural diversity that can mitigate the feelings of isolation and promote social integration, both for adults and children.

So, some sort of policy initiatives that aim at addressing systemic barriers to employment, to education, to social participation. These are all crucial for creating equitable opportunities for migrants to thrive in their new homes. I believe that one key avenue for improvement, I think, goes through the education system and how our kids, our children, feel safe and secure and happy and proud to have come from a background that has provided them with kind of additional worldviews, additional culture and linguistic skills, in addition to the societal language and the dominant culture.

So that’s the way that I think the education system should have some policy strategies in place for our kids to make them feel secure and happy about this kind of, you know, linguistic skills that they bring from their home countries.

Brynn: That’s a great point that we can kind of as community members do everything that we can to make people feel included, to encourage linguistic diversity and to encourage family languages. But you’re right that there needs to be something that’s a bit more top down in the governmental policies in education because that’s such a huge part of any child’s life and they spend so much time there. So that’s a really great answer. Thank you.

Shifting gears a little bit, I’d love to ask you about your actual experience in writing this book, Life in a New Language. Co-authoring this monograph with five other people, six of you total, had to have been complicated, especially because it was largely written during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Can you tell me what were the ups and downs of the writing process? What was that like to co-author with so many people?

Dr Motaghi Tabari: Actually, for me, this kind of, this collaboration was wonderful. So, collaborating with diverse team of authors certainly to me was an immensely rewarding experience. And one of the kind of major upsides I could say was the wealth of perspectives and expertise that each member brought to the table.

Clearly, like every other project, there are some challenges, particularly our research fell during the period of COVID, as you mentioned. And there were some challenges, if you want to call it challenge actually. So, it was just like coordinating schedules or, I don’t know, like navigating different opinions.

So we wanted to make sure that there is a good kind of, I mean, coherence across multiple chapters, how we could achieve that. But nonetheless, our shared commitment to producing a comprehensive and impactful kind of work kept us motivated and focused throughout the writing process, I would say. So ultimately, I would say this kind of collaboration and the collaborative nature of our work allowed us to produce this book that I think reflects by itself the collective insights and contributions of my amazing colleagues.

Brynn: And that’s what I think is so interesting about this particular book, is that it brings so many different types of people together in the stories, because you really feel as a reader that you’re getting a deep insight into migrant perspectives from all different cultures, all different language backgrounds, so you can see what’s different for certain people, but also the themes that keep coming up for migrants of all kinds. And I agree that the co-authorship is a really interesting and unique aspect to this book.

Before we wrap up, can you tell me what’s next for you? What are you working on now? What’s your next project? What are you up to?

Dr Motaghi Tabari: Currently, apart from my academic roles, I’m cooperating with some not-for-profit organizations as well, actually working on new projects. The projects that explore the language needs and challenges faced by kind of more vulnerable group of people in our community from coming from linguistically and culturally diverse backgrounds in health sector. You know, overall, my goal is to continue contributing to the ongoing dialogue about multilingualism and diversity.

And I would love to put theories into practice in real life. I love to see tangible results and if I can have any kind of positive impacts on the lives of people. And I would love to focus on promoting equity, understanding and social change as much as I can.

Brynn: Well, you’ve certainly started to do that with this book. That is very evident in Life in a New Language, so thank you to you. Thank you to your co-authors. And thank you so much for talking to me today, Shiva. I appreciate it.

Dr Motaghi Tabari: It was great to be here. And thank you for having me here. Thanks for it.

Brynn: And thank you for listening, everyone. If you enjoyed the show, please subscribe to our channel. Leave a five-star review on your podcast app of choice and recommend the Language on the Move Podcast and our partner, The New Books Network, to your students, colleagues and friends. Until next time.

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a

Join the discussion One Comment