***

Anna Dillon and Sarah Hopkyns

***

Figure 1: Sarah (in black) and Anna (in purple) at Abrahamic Family House

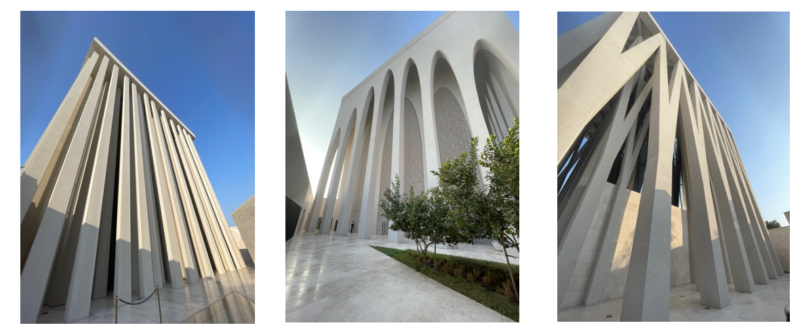

As friends and fellow sociolinguists, we, Anna and Sarah, have discussed almost every topic under the sun (literally!) on our balmy afternoon walks in our home/second home of Abu Dhabi. However, one topic we hadn’t discussed until recently was languages used within religions. Our visit to the Abrahamic Family House on Abu Dhabi’s Saadiyat Island changed this (Figure 1).

Linguistic and semiotic harmony across religions

It’s not often that you see Arabic, Hebrew and English represented together in the same space, but that’s exactly what the Abrahamic Family House does. This cultural and religious centre contains a mosque, synagogue and church as places of worship, linked together by ‘the Forum’, a secular and yet multi-faith connecting space or third space. One of the first features you are drawn towards is the Forum’s water fountain, which highlights the importance of water as a symbol of purity and ablution in Islam, Christianity and Judaism.

Figure 2: Trilingual signage at Abrahamic Family House (picture taken by authors)

All the top-down permanent signage in the Abrahamic Family House is trilingual (Arabic, English, Hebrew), and produced in such a way that the languages are equal in size and are represented on an even footing (Figure 2), with order of languages being alphabetical. This ethos mirrors the design of the mosque, church and synagogue themselves, which are represented equitably – with each building being a 30m x 30m square (Figure 3).

The numerological landscape also holds meaning in this space, with the number seven being significant in all three religions, and therefore represented in the architecture. The gardens add another dimension to the semiotic landscape, within serene courtyards dotted throughout as well as the central raised garden which links all three houses of worship. Here, olive trees are significant in all three religions and are planted throughout, again symbolizing the collective and shared history of the faiths, and with regional trees and plants also indicating the shared regional origin of all three religions.

Language choices for religious signs

Figure 3: The church, mosque and synagogue at the Abrahamic Family House (pictures taken by authors)

As we headed back to the Forum from the gardens, we witnessed an interesting lingua-cultural turn in relation to the signage in one of the darkened rooms. Each corner of the room was lit up in turn by a gobo, with a crescent representing Islam, a cross for Christianity, and a menorah symbolizing Judaism (Figure 4).

Where the crescent was, a verse from the Holy Quran was printed in English and Hebrew only (not Arabic), while where the cross was, a verse from the New Testament in the Bible was printed in Hebrew and Arabic. By the menorah, a verse from the Holy Torah was printed in Arabic and English, and not Hebrew. Some very interesting linguistic choices were made in this room. Here, the emphasis is on sharing values across linguistic groups. Multilingual linguistic landscapes here serve as a pedagogical tool for learning not only about languages, but in this case, religions too.

Abandonment of trilingual values on bottom-up and temporary signage

Figure 4: Religious gobos in the Forum (pictures taken by authors)

When looking at the temporary and bottom-up signage in the space, however, trilingual patterns wavered. For example, if you wanted to attend a sign language course which was being offered as part of the community outreach program, the story told was in Arabic and English, and not Hebrew. In the gift shop, while the main signage was in all three languages, the descriptions of the items were given in English only. Similarly, if you wanted to borrow an abaya to follow the dress code, the directions were given in English only. This reminds us of similar patterns found in Covid-scapes in Abu Dhabi, where bottom-up temporary signage tended to be in English only, in an otherwise bilingual linguistic landscape. Furthermore, the digital linguistic landscape seen via the website of the Abrahamic Family House, is bilingual (English and Arabic), with Hebrew not being a language option. Here, we see, as in other multilingual global contexts such as Canada, trilingual efforts are imbalanced across spaces.

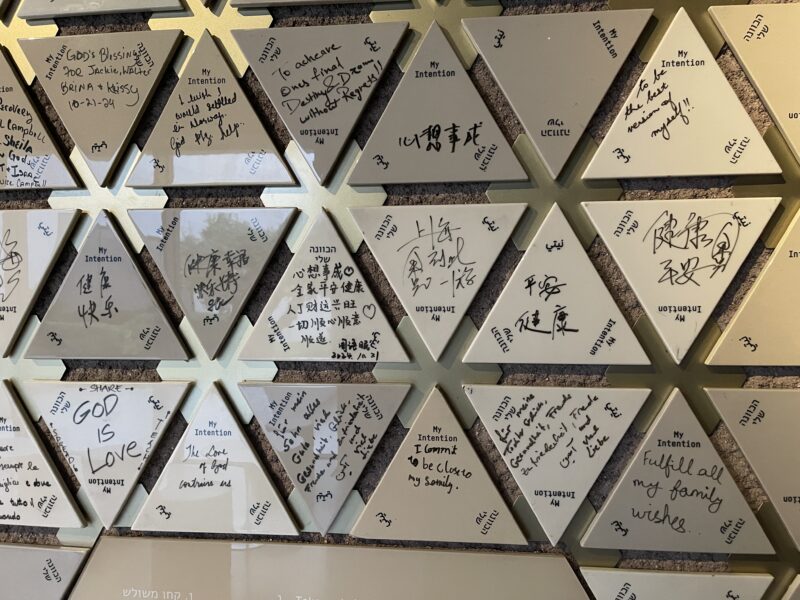

The wall of intentions

Figure 5: Multilingual wall of intentions (picture taken by authors)

Having explored the three places of worship and experienced the immersive light show (Figure 4), we came across a wall of tessellating triangles, again speaking to the significance of the number three: three languages, three religions, and echoing the shape of the simple triangular fountains found throughout the complex. We quickly realized that the purpose of this ‘wall of intentions’ was for visitors to write their own messages of intention. From 120 messages on the wall, we could understand the 60 messages written in English, eight in French, five in German, four in Spanish and one in Italian. A further six were written in Arabic, 25 in East Asian languages, and 18 others which we have yet to fully translate. Pictures appeared on 24 of the messages in addition to text, with only one intention including a picture without words, which was three people holding hands together, symbolizing togetherness.

Of the 78 intentions we could understand, 11 of them referred to God and only one indicated a prayer of any kind. Love was mentioned in 24 intentions, sometimes more than once to emphasize it. Peace was mentioned in 22 intentions. Other sentiments expressed included luck (five times) and happiness (seven times). Intentions were sometimes made in general, other times for oneself, for example ‘to be stress-free’, while sometimes they were made for the world (ten times), and for family in general or specific family members (12 times) (Figure 5).

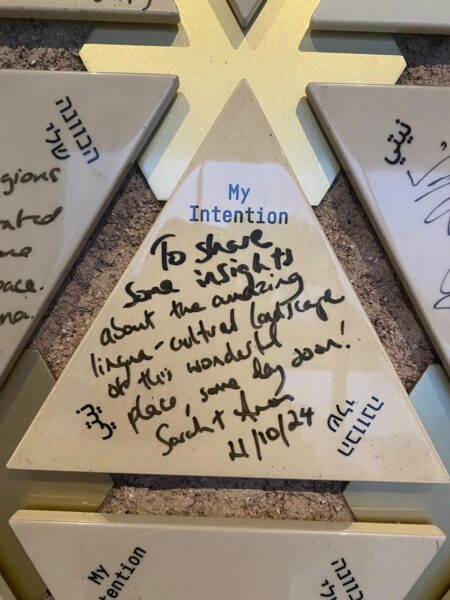

Figure 6: Our intention for further research (picture taken by authors)

Although the wall of intentions is temporary with today’s intentions being different from tomorrow’s, a major takeaway on the day we visited, October 21, 2024, was the focus on love, peace, the world, and family, rather than on religion itself. There is no doubt that further analysis which includes specific and detailed translations will reveal more nuanced truths, but that’s for another day. Suffice to say that there is a lot to get excited about in this multi-faith, multilingual and interculturally rich space. As our hand-written intention states (Figure 6), we plan to delve deeper into this rich landscape and add to the growing research on religious linguistic landscapes and semiotic religious landscapes in the Arab Gulf States and beyond.

Author bios:

Anna Dillon is an Associate Professor at Emirates College for Advanced Education in Abu Dhabi. She is a teacher educator in the UAE, and has research interests in early childhood education, teacher education, language and literacy education, multilingualism and translingualism in education and within families.

Sarah Hopkyns is a Lecturer at the University of St Andrews and a visiting research fellow at the Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies. Her research interests include language and identity, language policy and linguistic landscapes. Sarah is author of The Impact of Global English on Cultural Identities in the UAE (Routledge, 2020) and co-editor of Linguistic Identities in the Arab Gulf States (Routledge, 2022).

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a

Thank you, Sara! Your point about the longstanding trilingual linguistic landscape of the Old City of Jerusalem is very interesting. This combination of languages (Arbic, English and Hebrew) in one space is a recent development in Abu Dhabi and quite unusual in the Gulf overall. The inter-faith space was really well thought out and beautiful to explore. Yes, the language choices around the religious gobos were very interesting indeed! We are planning to do more research on this topic. Will keep you updated!

Ach, Paul, while a universal language would be epic in some ways it doesn’t seem to be how us humans work in society. For the time being, let’s language together, qu’est-ce on dit? Stimmt?

Too true. Anna, but some civilizations did get their act together if only for a century or two. A little issue, if I may: The notion of a ‘universal’ language understandably puts lots of people off but an auxiliary language (auxlang) for every school kid in the world (in addition to their mother tongue) as was proffered officially in favor of Esperanto at the League of Nations in 1919, and looked like a shoo-in after the carnage of WW1 until the French delegate vetoed it, is a different kettle of fish. Wikipedia’s article * alludes to the role of Henri Bergson and Albert Einstein in the International Committee on Intellectual Cooperation (UNESCO’s forerunner) and how they corruptly, if not venally, ensured the Resolution’s demise. * Top photos of those two stars just as they became really famous feature therein. I’ve chronicled gratis the whole unsavory saga bilingually under the rubric:

DIPLOMACY IS IMPOTENT

WHAT WENT SO WRONG AT THE LEAGUE OF NATIONS IN THE EARLY 1920’S

MIRRORS WHAT IS STILL GOING WRONG AT THE UNITED NATIONS TODAY!

LANGUAGE IS THE KEY!

While it might be difficult to separate linguistic issues from political issues – and it is – I don’t believe that the creation of a new language would necessarily solve those issues. It might just create a whole other set of political issues. Mind you, I understand the effort in making a neutral language. But, for whom would the language(s) be neutral or even inclusive? How privileged would one need to be in order to learn it (or them)? We would all face the same situation. We try to understand each other in one way or another. In fairness, we even get that misaligned when we speak the apparent same language. I speak English, which English? In which version of world Englishes would any of us be best understood? I speak school German and French, and so on… but no one is going to entertain me in Les Grisons, really, are they. A common language is a lingua franca. I think the point we were trying to make here was a point about common understanding, given all the languages involved (and we’ve only hit the tip of the iceberg). Isn’t it fabulous that these languages can exist together?

Very interesting read about such a unique and debated site in the Gulf! It feels like they tried to bring a touch of the Old City of Jerusalem—where trilingual signage in Hebrew, Arabic, and English is common, and mosques, synagogues, and churches exist side by side—to Abu Dhabi. The part about displaying verses from the Torah in Arabic and English (but not Hebrew) or the Quran in Hebrew and English (but not Arabic) really stood out to me. Definitely a bold choice!

My dear old mother long deceased, Brigid Conlan, taught me how the English in charge go about things. ‘Tanks mum’, as they used to say in Eire. I’m still saying my prayers, I promise. Rest easy! Hell, with French heritage in the male line, albeit from seven generations ago, this old Aussie recognizes Anglophilia. Too many notes in Mozart’s music becomes too many questions in an academic’s modus operandi when a hot potato appears. Keep ya hair shirt on, Brits. Just kidding! Question time is good for early risers Anna, but answer time is better for everyone. Wisely, your many questions start with ‘create’, and close with ‘belief’.

To ‘create a whole other set of political issues’ is exactly what is required as the Donald takes over leadership of the free world – tomorrow. OMG! A skeptic’s “I’ll believe it when I see it” becomes a religionist’s “You’ll see it when you believe.” BUT, by religion is meant that which is ascertained by investigation and not that which is based on mere imitation.

The road, or in this case the wall to perdition, is said to be paved with the best of intentions. I was climbing the bloody wall on bringing to mind how diversified the Babel story-myth-legend-teaching became when the leaders of the Abrahamic traditions instructed their writers what to record. (Wikipedia provides a mind-boggling and polished account of their three different interpretations and throws in a few more back to Gilgamesh.) Self-evidently, what’s required is for the UN or its next iteration or the parliaments of the world to SELECT A UNIVERSAL AUXLANG for every school kid in the world (or at a minimum to start agitating for one!) before the Middle East goes up in smoke and sees billions of victims elsewhere evaporate in the same vortex. Esperanto would be the fairest choice but the language of Shakespeare or Ogden’s Basic English are all fine by me, as long as something, anything, is done instead of the hand wringing and highfalutin belly aching and impotent (not useless!) diplomacy that goes on ad infinitum today. I don’t see anyone on this site objecting to either variant of that imperial, colonial, racist & grossly sexist alternative we all call the English language, what?