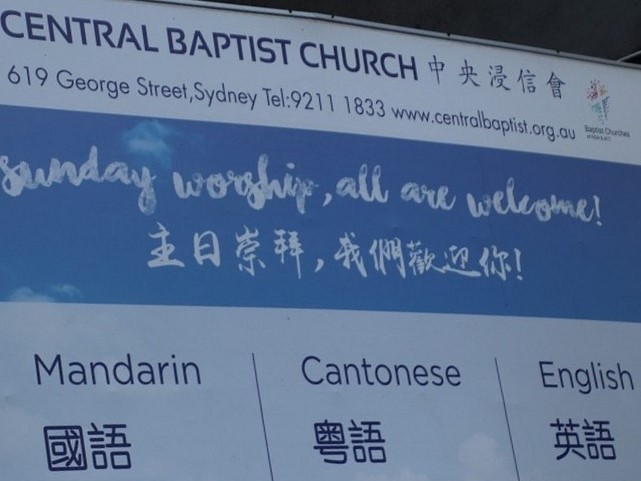

Chinese signage on churches is increasingly prominent in Sydney’s linguistic landscape. These signs are surprising because they are bilingual in a predominantly English monolingual linguistic landscape. They are also surprising because Chinese is not the language of a traditional Christian population. Chinese-English bilingual church signage is evidence of a growing trend towards conversion to Christianity among Australia’s Chinese population.

Chinese signage on churches is increasingly prominent in Sydney’s linguistic landscape. These signs are surprising because they are bilingual in a predominantly English monolingual linguistic landscape. They are also surprising because Chinese is not the language of a traditional Christian population. Chinese-English bilingual church signage is evidence of a growing trend towards conversion to Christianity among Australia’s Chinese population.

In a new book chapter, Yining Wang and I explore the conversion experiences of a group of first-generation migrants from China. Our interest in the intersection between conversion, settlement, and language learning was not only raised by bilingual church signs but also by the fact that many of the Chinese families in Yining’s PhD research about heritage language maintenance were interested in Christianity. Eight of the 31 participating families had converted to Christianity since coming to Australia and others professed an interest and occasionally attended church.

The reason Christianity was such a popular topic among these families was that many participants struggled with parenting in Australia. They did not want to raise their children in the strict and uncompromising Chinese ways they had been raised themselves, but they did not find western parenting appealing, either. They regularly shared horror stories of out-of-control westernized children who failed academically or had slid into drug addiction and promiscuity. Against this background, joining a church was frequently pondered as a middle path that might allow parenting that is both relaxed and emotionally connected yet guiding the next generation on a path to good morals and a fulfilled life.

A call for papers for a book about multilingualism, religion, and spirituality in Australian life provided us with an opportunity to explore the intersection between conversion and settlement further. We interviewed seven first-generation migrants from China about their pre-migration religious beliefs, their post-migration conversion journeys, and the role of Christianity in their language learning, settlement, and parenting experiences.

Arrival crises

The participants are highly educated and hold at least a Bachelors’ degree, which they obtained in China. Prior to migration, all of them had worked in professional roles in academia, engineering, finance, IT, and medicine. After migration, all experienced downward occupational mobility.

The transition from enjoying stable professional careers in China to their inability to find employment at their level in Australia came as a deep shock for the participants. Their economic insecurity was compounded by an attendant loss of status and self-confidence, strongly related to the language barrier, which made them feel incompetent. Their inability to re-establish themselves as highly successful competent adults in public turned into an existential crisis through the ways in which this affected their marriages and their relationships with their children.

One participant summed up the trauma of migration by saying: “We felt broken, both emotionally and physically.” The existential crisis of migration constituted the beginning of their religious seeking. Six of the seven participants used the exact same phrase to describe the situation in which they found themselves during their early time in Australia: “人的尽头” (rén de jìntóu; literally “the end of humans”; “ultimate hopelessness”). And where human capacity ends, the divine begins, as they went on to say: “神的开始” (shén de kāishǐ; “the start of God”).

One participant summed up the trauma of migration by saying: “We felt broken, both emotionally and physically.” The existential crisis of migration constituted the beginning of their religious seeking. Six of the seven participants used the exact same phrase to describe the situation in which they found themselves during their early time in Australia: “人的尽头” (rén de jìntóu; literally “the end of humans”; “ultimate hopelessness”). And where human capacity ends, the divine begins, as they went on to say: “神的开始” (shén de kāishǐ; “the start of God”).

Conversion as turning point

Spiritual seeking was not the primary purpose of turning to church, as the participants freely admitted. What they sought initially was practical support in the crises they experienced by making new friends that could fill in for the networks they had lost through migration.

The practical assistance offered by the church community helped to build up a supportive and trusting relationship that could partly compensate for the loss of family and friendship networks in migration. One participant explicitly framed her church as family: “I don’t go to church to attend activities. The church is my home. And I go home every week to see my family.”

Gaining entry into this new community, of course, involved accepting beliefs that were, initially at least, alien to them – most notably belief in the existence of a transcendental deity. Such a belief constituted a complete break with their strong socialization into atheism and the scientific worldview.

Overall, what started out as a search for practical support to face the existential crisis of migration resulted in a radical transformation of the participants’ social networks and belief systems. In the vocabulary of their new faith, participants repeatedly stressed that their new beliefs had led to “生命的翻转” (shēngmìng de fānzhuăn; “complete life transformation”).

Hybrid identities

At the time of the interviews in 2020, the average time since baptism had been more than ten years This means that not only the crisis of initial settlement but also the period of transformation through conversion was well in the past. Participants had had time to consolidate their new identities, and they had become comfortable in new hybrid identities as Chinese-English bilinguals and Chinese Australians.

Multilingual practices were central to their new faith. Participants had discovered that different languages and styles touched them differently. In the same way that both languages contributed to their spiritual development, their dual identities became fused, too.

For the participants, successful migration was ultimately a fusion of different national, linguistic, and religious identities; an integration of languages, national identities, and belief systems. This integration allowed the participants to find a comfortable space for themselves as first generation migrants in Australia. However, grounding the next generation in such a positive hybrid identity was more complicated.

Migrant parenting

As mentioned above, our study of conversion, settlement, and language learning developed out of a study investigating heritage language maintenance. That study – like many others with many different migrant groups – found that English dominance of the second generation is the most frequent heritage language learning outcome. While oral proficiency may be more variable, Chinese literacy levels were consistently low in the second generation.

These differences in linguistic repertoires between migrant parents and their children may result in discursive gaps between “Chinese parents” and “Australian children.”

Partly due to different linguistic repertoires, participants perceived Australia’s individualistic culture as constituting a formidable threat to their parental authority. They felt that Christianity allowed them to bridge this gap by providing an objective source of moral reference. Ironically, Christianity thus provided the participants with the vocabulary to instill what they considered Chinese values in the second generation.

Partly due to different linguistic repertoires, participants perceived Australia’s individualistic culture as constituting a formidable threat to their parental authority. They felt that Christianity allowed them to bridge this gap by providing an objective source of moral reference. Ironically, Christianity thus provided the participants with the vocabulary to instill what they considered Chinese values in the second generation.

Lessons for secular institutions

Our study holds three key lessons for migrant integration into secular institutions.

First, we noted that the experience of migration triggered an existential crisis for the participants. This crisis arose from a combination of economic insecurity, loss of status, the initial language barrier, marital difficulties, and parenting challenges. These migration traumas were closely connected to the loss of social networks in migration. The absence of family and friendship networks itself was deeply unsettling. Furthermore, it could escalate relatively mundane problems (e.g., who to call in the case of a power outage; how to send a sick note to school) and elevate them to personal crisis level. Church groups provided instrumental support to address these problems. This included a host of practical matters but, most importantly, the creation of new social networks. We would argue that in a secular society practical settlement support and human fellowship through new network building should be accessible to all migrants, irrespective of whether they accept a new belief system or not. To this end the provision of culturally-sensitive migrant support services particularly in the initial settlement phase is of paramount importance.

Second, in the long-term, participants thrived by engaging in English-Chinese bilingual and bicultural practices. Being able to draw on both their languages and cultures, and bringing them together in a holistic hybrid fusion made them feel settled and comfortable. The Christian congregations they attended were pragmatic about the use of bilingual repertoires. They also readily combined Christian and Chinese ways of doing things, as long as core doctrine was not affected. This linguistic and cultural syncretism significantly contributed to participants’ long-term language learning, settlement, and overall integration into Australian society. This constitutes a significant contrast between these Christian churches and secular institutions such as schools, universities, and workplaces. The latter continue to implement exclusive English-only practices ingrained in their monolingual habitus.

Third, all parenting is challenging and migrant parenting maybe even more so. How to guide the next generation to keep them save from harm, to fulfil their potential, and to lead ethical lives contributing to the common good can be an enormous source of anxiety for migrant parents as they navigate not only generational but also linguistic and cultural gaps. The parenting experiences documented here show a clear failure on the part of Australian schools to minimize those gaps. This failure is twofold: first, it relates to the well-documented inability of the Australian school system to support the language learning aspirations of heritage language learners. This means that the second generation, by and large, does not have the capacity to deeply engage with the discourse worlds that shaped their parents’ socialization, world views, and values.

Second, it relates to weaknesses in institutional communication with parents from non-English-speaking backgrounds. This means that parents lack a good understanding of their children’s Australian education. This may give rise to fears of and anxieties about the education their children are receiving. In the interest of social cohesion, it is vital to overcome these barriers by improving heritage language education and home-school communication.

To read the full study, access this open-access preprint:

This lecture – delivered as a keynote at the 2021 Approaches to Migration, Language, and Identity conference – offers another way to learn about the relationship between conversion, settlement, and language learning:

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a

Firstly, as I am an atheist (no offence, just not deeply exposed to the field), I don’t know much about religion so far, but through this article I seem to understand why so many people have their own religion. And I agree that there are language differences between parents and children of migrant, As I have the same experience. I am a Chinese but have lived in Japan since I was little, so I have a little bit of empathy. Since I went to Japan after I had fully acquired Chinese, my first language isn’t too bad, but as I live in Japan for a longer time, I become rusty with Chinese. As I was not in the Chinese community in Japan, I did not have many opportunities to use Chinese. However, it is not possible to forget it completely and it is easy to refresh your memory by using it intentionally and frequently.

But I think it would be different for me if I had been born abroad or had migrated to a foreign country without acquiring a first language. It feels like it’s easy to see English as a first language because you haven’t had deep exposure to the language of your home country.

In the end, I couldn’t agree more with this statement! “Successful migration was ultimately a fusion of different national, linguistic, and religious identities; an integration of languages, national identities, and belief systems. “

Migration to another country is a scary prospect with a host of challenges, the loss of social networks and support systems not least among them. That Chinese migrants might convert to Christianity to restore structure in their lives post-migration is both interesting and understandable.

Most Christian denominations offer a socially conservative moral framework that espouses traditional family values, woven from a cohesive fabric of community identity. This sense of belonging to something greater than oneself and adherence to (comparatively) stricter social norms may prove familiar to like-minded Chinese migrants.

But should religion be a secular person’s first port of call? Multilingual language support in the education system in the form of published materials, seminars, and hired staff would certainly address some of these issues. Having a child in the education system affords L1 English-speaking parents with opportunities to socialize in school-sanctioned activities; can mixing and mingling events that cater specifically to L2 parents not be similarly arranged?

All too often, non-native speakers of English are rendered invisible in Anglo society. It is the responsibility of this society to lower the barriers to entry and make concerted efforts to reach out and welcome L2 speakers into it more fully.

Well said – secular institutions certainly can learn from churches in this regard …

It is true that churches offer migrants and international students a lot of help physically and emotionally at least according to my experience studying in Australia. I believe that Chinese international students have experienced visiting churches even though they were not Christians in China, which might be one of the reasons that the Chinese Christian population is increasing. My friend’s mum who lives in Brisbane does not speak English at all invites her Chinese Christian friend to come over to her place regularly to read the bible together which is a way to prove her social identity and ease her loss of social network feelings in Australian society. But it is limited in English-domain society. As nowadays the Bible has been translated into Mandarin and Cantonese versions which promote the public, Churches can be the bridge to fill the huge gap between Chinese parents and their Australian children in the ways of cultural, age, and language differences.

Brighton Rockdale Anglican Church- a Chinese Christian Church in Sydney.

With the sharp increase in the number of Chinese immigrants in Australia, and a large number of Chinese and other Chinese-speaking areas studying abroad in Australia, in response to this huge evangelistic need, the church established Chinese-language worship in 1992. They believe that God has chosen them for their salvation, and called them to follow Him and become His disciples, in order that they obey the greatest commandment and the greatest mission commanded by the Lord Jesus, namely, to do with all hearts, and with all their souls, and with all strength. Love the Lord and love neighbors, lead them to Jesus Christ, nurture their spiritual growth, train them to serve God, serve people, and preach the gospel to the unheard.

This article hits close to home, especially because when my family went to the United States with my family, my dad’s colleague’s family invited us to a Korean-American church and we began to attend services there. Korean church communities are very active and provide many opportunities for migrant families to get to know each other and build new relationships. Like the Chinese Baptist community in Australia, Korean parents also see Christian values and community as good influence on their children. So even if they are not Christians, many Koreans attend church. Korean churches often hold worship services in Korean for adults and English for the youth. Children learn the Bible in English, which can also mean that Christian values were instilled in the children in English. Although parents learn Christian values in Korean and children learn in English, the family shares the same values and this can be the bridge between migrant parents and children.

This is a very interesting phenomenon. I’ve noticed many Chinese churches in Sydney myself before and found it remarkable. Religion indeed plays a captivating role in acculturation of migrant groups. I recently saw a Ukrainian Catholic Church in Lidcombe.

Christian life in Ukraine itself is quite complex. Ukrainian Catholicism is the religion of the Western Ukrainian region of Galicia. It is theologically Catholic, and affirms the authority of the Pope, yet its rites are Eastern. This is because the church used to be Orthodox, but entered a communion with Rome in the 17th century. The rest of Ukraine still is Eastern Orthodox. Until very recently, Ukrainian Orthodoxy was largely a branch of The Russian Orthodox Church. It was only in 2018 that the independent Orthodox Church of Ukraine was recognised by the Patriarch of Constantinople, which was a culmination of a slow process of many congregations switching allegiance to several then-unrecognised Ukrainian Orthodox Churches.

Considering this, I wonder if many Ukrainian migrants with a non-Catholic background have decided to join the Ukrainian Catholic church once in Australia. Such a phenomenon could be possible both due to the stronger Ukrainian identity of the Catholic Church, and the higher piety of Western Ukraine, and thus more vibrant church life and stronger support networks in the Ukrainian Catholic Church. Catholicism, even with Eastern rites, is also implicitly more “Western” than Orthodoxy, and could act as bridge between a migrant’s native culture and the Australian culture, in a similar way to the golden-middle image of Christian morality for Chinese migrants discussed in the article. This could be aiding integration without the migrant having to abruptly adopt completely alien church identity. Western Ukraine is also the most solidly Ukrainian-speaking part of the country, so interesting linguistic developments could also be happening with such migrants.

This would be an interesting multidisciplinary topic to explore.

Great research topic, Alexander! Maybe an MRes project? ☺️

In my opinion, churches definitely have a significant role in creating an inclusive and save environment for migrants and workers in a foreign country. When I was studying in Japan, I found great loneliness and challenge integrating to the Japanese culture. I guess since Japan is such a homogenous and particular culture, it’s hard for most foreigner to fit in and not stand out. I myself, as a Vietnamese – Japanese translator had witnessed the problems Vietnamese workers faced being discriminated at work and getting in trouble just because they are foreigner. Therefore, the first stages of learning the language and culture are vital for anyone visiting Japan, especially manual workers who are the most vulnerable. Churches in Japan provide a safe environment for migrant manual workers, mostly from Indonesia, Nepal, The Philippines, and Sri Lanka. They offer Japanese lessons, consultation (both in terms of mental health and support on ways to settle in Japan). They provide a communal ground to share and to care. Most migrant factory workers in Japan I know are always in need, so the church often offer lots of charity for them. I could also see the same kind of support coming from other religious organizations such as Buddhist temples or Muslim churches. Having a place to belong is very important migrants’ lives and I think governments should strive to be the pioneers in this matter, not just charitable organizations.

Thank you, Nguyen, for providing another important perspective!

Dear Ingrid,

Thank you for sharing this wonderful article. I learned several reasons why the first generation of Chinese immigrants in Australia believed in Christianity. This phenomenon also occurs in the United States. Many first-generation Chinese immigrants in the United States may face special pressures in adapting to American culture. In order to satisfy their spiritual and psychological needs, many non-religious Chinese become Christians, and some Chinese Buddhists also convert to Christianity after they come to the United States.

Chinese culture attaches great importance to traditional marriage and family life. Immigrant Chinese parents rely on the Christian Church to carry out meaningful and attractive youth activities, aiming to keep immigrant youths away from the potential impacts of American society, which are considered to have an impact on the destruction of traditional marriage and family values. Research found that there is a strong relationship between religious devotion and marital satisfaction. Religious beliefs, common religious rituals and values seem to have a positive impact on marriage and family relationships in Chinese immigrant communities.

Reference:

https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1515&context=gradschool_theses

Thank you, Siyao, for the additional perspective!

Thank you so much for the post, the article and the lecture!

I cannot help but make a connection between this content, the post/podcast interview about multiculturalism with Prof. Pavlenko, and how the linguistic ideology of “one nation, one language” permeates secular practices in regards to lack of support for migrants.

As mentioned in the podcast, the languages of immigrants are often devalued and the use of multicultural resources such as signage obeys practical reasons rather than a truly multicultural perspective. That same foreign language devaluation is reflected in the lack of support for migrants whose English level may be low or even inexistent and even in educational contexts where parents from different cultural backgrounds cannot engage in their children’s academic processes and children do not have the chance to develop their heritage language skills due to English being the only language for communication.

Even if the main reason for churches to use other languages is facilitating conversion, it could be argued that their pragmatic efforts to not only provide religious information in the migrants’ L1 but to also support them in their adaptation journey have a more multiculturally inclined perspective than secular practices that may seem multicultural only on the surface. It is great to know that migrants can access this kind of support from organisations such as churches, given the absence of said support from secular organisations.

As an international student myself, I also have (and continue to) struggle with the absence of support networks in my new environment. I also had the chance to briefly experience the support provided by a church in Sydney (which, by the way, has the word ‘international’ in its name). There, I encountered a very varied group of people from all parts of the world, with varying levels of English proficiency who were all joined by their faith and the accompaniment provided by church members who look out for all attendants, especially for newcomers, irrespective of their background. Although at first not having the same belief system is not that big an issue, it is obvious that eventual engagement and conversion are required to continue belonging to that community.

It would be great, as mentioned in the post and the article, that secular organisations offered similar support services, especially for those of us who may not share the exact same religious beliefs as churches that currently do. After all, whether you are a temporary or permanent migrant, you become part of the target society (even if it is for a while), so adaptation is not only beneficial for you as an individual, but also for the community you are joining.

Thank you, Ness! You are making such an important point that is frequently overlooked: a class of outsiders is not only detrimental to the outsiders but the whole of society!

Thank you for sharing this research blog!

When it comes to the relationship between the Chinese immigrant family and the church, this reminds me of my landlord. They are immigrant families. Because of their Buddhist beliefs and to find a sense of belonging, they often go to the Nantian Temple in Wollongong, which is known as the largest temple in the southern hemisphere, to worship. As a layman who has converted to Buddhism, I naturally go with them. I think this is similar to this research blog. Many Chinese immigrant families did not have religious beliefs before they came to Australia. However, after immigrating to Australia, many families will begin to have religious beliefs and join the church. But for Chinese immigrant families with religious beliefs, they will naturally find religious sites about their beliefs in Australia. For example, churches are places for Christianity and Catholicism, and temples are places for Buddhism.

Thank you for the article. I feel that the influence and power language has over people’s lives is still not discussed enough in current educational systems. In the case of the Chinese immigrants coming to Australia, despite being highly educated, they experienced downward career mobility because of a language barrier, among other things. This is not unique to Australia and is also experienced in other places around the world. For example, an Australian engineer moving to China without Chinese language proficiency would also likely experience downward occupational mobility.

Even though a foreign language class is often required in secondary and post-secondary education, I think the importance of knowing other languages and their connection to future opportunities is not made clear enough. From my experience teaching English in Japanese secondary schools, students typically do not know why learning a second language is important for their future. They see the class as something they must get through in order to graduate. I unfortunately felt the same in my high school required Spanish language class. Now as an adult, I know it was a class I should have taken more seriously. The importance of second language acquisition should be made clear to students as opportunities to live and work in different countries become more commonplace.

Hi Ingrid thanks for sharing the research.

This research was fascinating and at the same time a very familiar topic to me. I have many people around me and my family who have the same experience you mentioned in this post about reaching to churches even though they had no faith before migrating to Australia. I’ve heard personal stories about people actually going to churches because they were struggling to survive in Australia and like you mentioned, thought that going to church will allow them to form networks and connections. And I totally agree with your point about 2nd generation migrants. I’ve seen so many 2nd generation migrants not interested in learning their mother tongue nor the religion their parents converted into and are more focused on climbing the social ladder in the Australian society.

Thank you for your sharing.

In fact, no matter which country in the world, immigrants will be very confused when they first contact the new culture, language and life. Fortunately, the church has a lot to offer in this case. Through churches, people can expand their social circle and blend into a new environment in many ways, chatting together, engaging in entertainment and inviting each other to dinner. It was a sweet home for immigrants.These will be of great help to education and other aspects of life and accumulate a lot of experience.

Hi Ingrid, thanks for sharing this article.

It is interesting to know more about how religion is helping migrant communities to form a place of togetherness. I didn’t know earlier just how important is the Chinese community church to Chinese migrants in Australia. Also, I think it’s true how Chinese families wanted a mix of how to bring up their children; they didn’t want the strictness of Chinese culture, but also didn’t want too much influence from the west. The parents want(ed) their children to be disciplined, but also fair.

There are many examples of migrant communities establishing places of worship, especially in Sydney. For example; the Polish community have a Polish church, pre-school, and aged care facility in Marayong. About one or two decades ago, the church was the central meeting point for all Polish people living in Sydney. It still is a place where many Polish people would share the language, culture etc. The parents usually sent their children to Saturday schools in the morning to learn Polish. The church was more than a place of worship, it was a cultural center and meeting spot for every Polish person in Sydney and to ‘get away’ from Australia from time to time.

Thanks, Ian, for sharing this perspective from the Polish community!

Hi Ingrid,

Thank you for your sharing! I was surprised about the relationship between churches and Chinese immigrants in Australia but I know the church group has strong connection because my uncle is Catholic and he has told me a lot about his church group. E.g. Each month his church group will take turn to organise BBQ party in their houses or they decorate the church on Christmas together. Or my friend, she is Catholic, too and she met her husband when she joined the church group.

However, I don’t agree with point the Christianity can bridge the gap between “Chinese parents” and “Australian children.” The religion only gives us moral standards through the Bible, tenets … which guides us do the right things. But if the parents want to understand their children, they must spend their time to talk and listen to their children, the religion can not force their children listen and do what they want.

It is a relief that Chinese migrants receive some help from their church regarding the issues related to language barriers, parenting, and other existential crises that emerge during their initial settlement in Australia. As I’m a Christian belonging to a fairly big congregation located in Seoul, South Korea, I’ve known that the church provides some practical support to migrants from different language background like Philippines, Vietnam and Thailand. But I never recognized what kind of specific support the migrants have been receiving until I read this intriguing blog. I hope the migrants to my country handle their struggles through the church as Chinese migrants did in Australia, and adapt well so that they accomplish the goals they had set.

Thank you for this intriguing topic. I used to watch a lot of youtube’s videos about people from my country, Vietnam, sharing their migrant experience as well as their integration processes. It is mostly about the way they seek and join Vietnamese community organizations to expand their network. Thus, I was quite surprised to explore how Chinese immigrants develop their participation and integration into Australian society through religious activities. Based on those activities, the migrant churches facilitate members’ integration through the creation of spaces of well-being, fostering interpersonal relationships as well as providing moral and mutual support to educate their children. Therefore, I reckon that migrant churches might be an important key to better understand immigrants’ integration process.

I know how helpful religious groups can be for new arrivals. When I first arrived in Sydney, I was not surrounded by family and friends, and I did not know my classmates well. The language barrier and culture shock were overwhelming. I was inadvertently drawn into a club during orientation week, and the student who introduced me to the club invited me to participate in the activities, and I couldn’t refuse because they seemed very welcoming to a Chinese person who wasn’t fluent in English, which I had never experienced with other Australian locals. I found out that it was a Christian club after I officially joined the event, but the student who was in charge of organizing the event repeatedly emphasized that non-Christians could also join the activities, and that the purpose of the club was to let people expand their social circle and make more friends. It is important to note that most of the people in the club are Christians, so I was a little uncomfortable at first, as I was afraid that what I said would offend the religious beliefs of these students. Interestingly, the activities in the club were divided into casual conversations, games, and discussions about what you thought about a particular chapter in the Bible. Although I still have doubts about religion, I have to admit that the club I unwittingly joined did serve as a psychological cushion for me when I first arrived in Australia, so I didn’t feel alone and helpless for too long.

Thank you for this intriguing blog. I’ve never thought how the church could help migrants this much. I am glad that the Chinese in this blog found their “home, family, brothers and sisters”. I can see how difficult it is for a migrant to build a connection or to make friends in the receiving country. Probably they have tried so hard and in many ways to seek a friend, yet the results came out disappointedly. Frankly, this issue happens not only for migrants but also for international students. Even in an easy-approaching contact like schools or workplaces, it is still impossible for them to make friends. Language and cultural differences are amongst the reasons, but it is more complicated than that if we mention other factors.

Thanks, Tram! True that international students are another group who often face social isolation. The dream of study abroad is often rather different from the reality 🙁

This blog is interesting, Ingrid. I can feel the struggling emotions between Chinese parents’ traditional thoughts in terms of they want their children to be ‘good boys’/’good girls’ and the thoughts that they would like to be open-minded to their children. In this case, church, as a mediate, seems to be a good choice for them to balance these thoughts.

This blog reminds me my family as well. My parents are just like those parents who hope their children be active instead of traditional, and that’s also one of the reasons for why they allow me to study at MQ. However, meanwhile, they are also afraid that my thoughts become western, as for them, they still think western cultures are too open and free. They don’t want me to be a very open girl as well. So sometimes, they are very nervous when I told them my Australian friends invite me to go party, they will always remind me that I cannot wear short skirt something like that.

At MQ, I have many friends who always went to church, they hope to make friends, but they just went to the church that uses Chinese to pray. So for them, the language environment is still Chinese. And some of them even cannot communicate in English. There is another very interesting but also for me, an ironic phenomenon is that in Australia, some Chinese family teach their children English since they started to learn how to speak. But, when the children grow up, they began to teach their children Chinese, and as the children are get used to speaking English, so the parents have to pay for the professional teachers to teach their children Chinese. If the parents can use their bilingual advantages to teach their children both English and Chinese together rather than only 1 language, the children will be proficient in both English and Chinese. I guess this is also probably because the struggling emotions among Chinese parents. They want their children to be western thoughts, as they migrant in Australia, however, they also want their children to be Chinese.

Thank you, Yuxuan, for these insightful reflections! As they say, it’s complicated …

Lydia

This is a very thought-provoking article.

It is common for Chinese migrants in Australia to face language barriers and other problems, which leads them not to have a sense of belonging and even have difficulty educating the next generation. Church provides opportunities for these migrants to find out belonging and solve problems that migrants face in daily. The church is like a sanctuary to make these people feel warm. However, I wonder if the church is so magical that it can help these people find belonging? For me, I think it may be wrong because people’s faith is closely related to themselves. If you believe that the church can help you, and you can find out belonging. Therefore, I believe that it is not church or religion that help them solve difficulties or find out belonging; it is their beliefs.

I found this article and the accompanying lecture incredibly fascinating. What really struck me was the observation that Christian churches in Australia are providing these linguistic and social services to migrants in a way that secular organisations seem not to be. Why is that? Is it because secular services generally have to rely on government funding for language/social programs, but perhaps churches are relying more on volunteers who run these programs? Could secular services, even given all of the funding in the world, ever achieve the same level of migrant assistance as the churches, or is the faith element actually what keeps migrants in the community (even if that isn’t what necessarily drew them there in the first place)?

This is a brilliant and quite relatable article because I have actually seen that a number of immigrants in Australia are concerned about the influence of the Aussie culture that will effect their children provided the fact that they considered Australian culture more westernised than their native countries.

they believe sending their children to religious school where the teachings of their respective religion takes place. Contrary to that, I don’t believe in tagging a certain country/culture to any social stigma.

It reminded me of when I first came to Australia and my boss suggested that I could go to church to learn English and make friends. He believers that church provides an opportunity to practise English, share food and learn about Australian culture. I agree with the article that church is not only a place for newcomers to practice their language but also a place to find a place to belong. I read a piece of news that due to the growing congregation, which includes many immigarnts to the area, St Matthew’s Church in Adelaide has decided to take the extreme step of using the nearby bowling club as a ‘second base’ for the church, Grace Church, and to serve the surrounding area, which shows that the church really means a lot to new immigrants. Although the majority of these are Chinese, there are also believers from Singapore, Korea, and even France and Wales.

Thanks for sharing an amazing blog! We can see the popularity of Christianity nowadays and how it helps migrant parents minimize the linguistic and cultural gaps. It makes me remember a story of my boss. He is Chinese-Vietnamese and he came to Australia 40 years ago. Through the blog and his story, I can see how migrants struggled with the combination crisis. He told me his story “sailing to survive” and a severe journey to deal with economic insecurity, the initial language barrier and parenting challenges. Interestingly, he also sent his three children to Christian schools because he believes that these schools helps the parenting more relaxed but still disciplined and shapes the children with good morals. He also mentioned that participating in a church every Saturday is an ideal way to get closed to his children. He was very happy when seeing the kids get to know the culture and improve the language with people speak Mandarin, Cantonese in the Christian community. I would like to share with you how this guy has been successful in parenting second generation. His second daughter is not only very fluent in using Cantonese but also has a great passion with Chinese calligraphy and her father’s culture. Here is her website: https://www.tranliagraphy.com.au/ . She is such an amazing inspiration for everyone.

Thank you, Lynn, for sharing this story and, particularly, the link to the beautiful calligraphy website! Amazing project!

I found it particularly thought provoking that one family would need to worship and parent across two generation in two languages. The thought that the children of migrants would need to attend English language religious services while their parents were attending Chinese ones was very interesting as was the willingness of the churches involved to provide pragmatically based forms of worship for their followers in clear juxtaposition to services provided by the government. It shows that language can be used as a tool for achieving the purposes of an organisation outside the linguistic ideologies of languages as part of the national myth of a country. This could be applied to the case of the current pandemic in South West Sydney where local religious groups provided information to those who were not adequately receiving information from the government in a medium that they could more readily understand.

Thank you for sharing this post!

The relationship between churches and Chinese immigrants in Australia reminds me of the experience of one of my friends who has immigrated to Canberra for many years. She was a classmate of mine during my undergraduate period in Canberra. She came to Australia at the age of 10 and found it hard to fit in the local community, because of the language barrier and cultural, educational differences. This happened with her parents as well, her mother used to be a university teacher in China, however, her lack of the ability to speak English turned her into a full-time housewife in the new community. She said that the living in an English-speaking country, her mother had little choice but began to occasionally go to the local church because there were many Chinese people (especially women with children) who could not speak fluent English. Her mother felt relieved in the church as she has a chance to rebuild her interpersonal and social network.

So I couldn’t agree more with the point about how the language barrier and social insatiability can serve a role in turning people into Christianity. I feel like under many circumstances, Chinese immigrants went to church not because they truly believed in this religion, but because they wanted to make new friends and fitted with local people in a new language environment.

I take back my previous assumption that when it goes to the layer of beliefs and faiths multilingualism could happen to be more difficult vis a vis the layer of behavior. This inspiring article showed me a broad space for multilingualism growth and cross-culture fusion, and surprisingly it is provided by spiritual faiths. I’m not religious, but I can imagine that how tolerant people could be in this spiritual context and how much truehearted help these Chinese families have received from this environment.

I wonder what the polyglot context containing multiple languages and cultural backgrounds would bring to the religion per se? Or would it probably furnish the religion with an affordance to realize its doctrines? I am curious about that if an environment of multilingualism could both benefit the belief system and its believers.

Thanks, Anka! What our study showed was that these churches are agnostic (forgive the pun) about languages. Monolingualism or multilingualism is irrelevant to them but they are willing to work in whatever languages if it furthers their religious, spiritual and community goals. Personally, I find that quite admirable, particularly when compared to secular institutions, such as schools, who often prioritize a particular language (or languages) over their educational mission.

If you want to learn more about the role of different languages in different faiths, I would recommend Bennett, B. P. (2017). Sacred languages of the world: an introduction. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons.

It is really interesting how such research can reveal many facts about Chinese migrants and their relations with the church. However, I cant see that being Christian or following any religion would assure that your children stay away of drugs, alcohol or any other issue. Yes, religions teach people the right way but there is no guarantee that children are going to follow these teaching and believes.

This also reminds me of our first years in Australia, and the bad feelings we had because we didn’t know anyone here and there was a language barrier that prevented us from socializing at that time.

Thanks, WAA! Finding new networks and friends and being socialized into a new society as an adult is a huge challenge for all migrants, and one we often don’t take seriously enough. The advice that is often doled out in language learning textbooks (watch the footie, take up a sport, etc.) is mostly entirely inadequate. Joining a church is one such piece of advice that circulates among many migrant groups – whether it delivers or not is an entirely different matter; and the same is true for the belief that a religious education will produce certain educational outcomes: it’s probably not empirically true but it’s a strongly held belief of many people …

This blog reminds me of my experience of teaching Australian children of Chinese parents. Some of the parents prefer sending their children to either Catholic or Christian schools even they are atheists. I have been to a Catholic primary school in Auburn where a large number of Chinese families reside; the students are required to study the Bible and have religious classes every day as a part of the school curriculum. The Chinese parents often hold the belief that religious schools can provide a reliable and inclusive learning environment for children from diverse cultural backgrounds. The openness of religious schools embraces migrated families spiritually as they play essential roles in constructing a stronger sense of belonging for the younger generations. Additionally, the parents tend to feel reassured by sending their children to these religious schools rather than Australian public schools during elementary education. They think religious-related studies have a positive impact on their children’s behavior and maintaining good manners.

Language and communication barriers are the challenges faced by new immigrants in Australia. It makes them hard to find jobs and obtain medical care. It weakens the cultural experience. The loss of social-economic status and the change in the cultural environment create a crisis for new immigrants. From my observation, different levels in English make family members integrate differently into Australian society. The new cultural identity will impact the relationships between husband and wife.

It is very interesting that churches can address these issues. I’ve never heard that churches can help new immigrants to address mundane problems such as the case of a power outage. They can get a sense of belonging and get support from the church community. They can even “use” church to educate their children. However, it makes me think: will the new immigrants really have true faith?

This week’s information was once again very intriguing!

What I could really relate to was how migrants seek a community to feel a sense of belonging. In fact, even those who are not migrants and simply in their own country, seek communities that hold the same beliefs and values. Hence, it is only natural for migrants to seek such a community to compensate for the loss of networks.

My parents also moved to a new country (not necessarily a migration) and experienced that loss of network. It was more so for my mother than my father because unlike my father having a network of co-workers, my mother had to stay home and parent! After quite some time, she eventually went to church, to feel less lonely and find comfort from those who speak the same language!

The ability to speak the same language plays a huge role in bringing that sense of connectivity and belonging, which is why I can see how Christianity, or rather the churches were critical in bringing migrants to diffuse into the new community.

Thanks, Kim! Not speaking the language of those around you really is very isolating and lonely. It’s sad to see that there is often so little empathy for language learners …

Thank you very much for the presentation of research findings! I’ve never dealt with the migration issues in Australia bevor and many details impressed me a lot. While I was reading the blog post and watching the presentation, I compared impact of migration on people’s life in Germany and Australia. It is notable that migration leads to emergence of new identity and this way could be very challenging because of (temporary) loss of social-economic status, change of the cultural environment, social isolation etc. I was surprised that church supports language diversity in Australia in contrast to other social institutions. At the same time, I think (like Ivana in her comment above) that unfortunately heritage language (or particularly multiliteracy) is rarely pass to the 2th generation. It would be interesting to know how parents assess their multilingual competence and whether they consider it as a relevant resource for theit children.

Furthermore, it was fascinating that interviewees in this survey said that they find a new “family “in the church. It makes me think that not only participation on social institutions but also building informal supporting relationship is relevant for wellbeing of migrants. In Germany it is discussed a lot about participation of migrants on formal social institutions, while involving in informal conversation and activities are taken in consideration only partially. (Sauer, 2016; Carnicer, 2017)

At this point, networking and finding new contacts could serve as a basis for the further integration.

Thanks, Kseniia! How to make friends in the migration context has been a big question for most of the 100s of migrants my team and I have worked with over the years …

You might find this old blog post about the intersection of language learning and finding friends interesting: https://languageonthemove.com/learn-english-make-friends/

Thank you very much for sharing this link! I read this post with great interest and also reflected my own experience with the social integration in Germany.

If the social lives of migrants interest you, I would also recommend these:

Chang, Grace Chu-Lin. (2015). Language learning, academic achievement, and overseas experience: A sociolinguistic study of Taiwanese students in Australian higher education. (PhD), Macquarie University, Sydney. Retrieved from http://languageonthemove.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Grace-Chu-Lin-Chang_Taiwanese-students-in-Australian-higher-ed.pdf

Takahashi, Kimie. (2013). Language Learning, Gender and Desire: Japanese Women on the Move. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Thanks for sharing the research.

I personally found the research very attractive.

This research gives me the impression that the practical support in crises partly leads to the conversion. This is the secular side of the church. They come to God because he is helpful. How about the divine side of the church? So for me, they are still in the process of integration but not fully integrated yet if it is possible. There are differences between how they perceive God and how Australians do. How is that going to influence their identities? Or maybe I am wrong.

I know some foreigners working in universities in China and the church group they belong to. The group is very open and inclusive, so I have attended some activities out of curiosity. Members help each other to live better in China. It seems like a way of living, or an inseparable part of life. I started to think it as one of the church’s social function. Still I did not see the divine side of the church during activities.

It is true that most Chinese feel that “Jesus belongs to foreigners”. In fact, I am descended from a Catholic family in China. There is a over 100-year old church in my village, so as far as I know, the history can go back to at least World War II and maybe earlier. My grandpa said that there was a foreign Father who helped villagers during the war. To be honest, I am not so faithful, struggling between the religion and science-led education.

Thank you, Charity! There is a really good read about the Jesuit mission to China: Liam Brockey’s “Journey to the East” – maybe not directly relevant but v interesting case study of language and culture contact through religion: https://books.google.com.au/books/about/Journey_to_the_East.html?id=LEG1rG0dsU0C&printsec=frontcover&source=kp_read_button&newbks=1&newbks_redir=1&redir_esc=y

It was fascinating to learn how conversion to Christianity among Chinese migrants in Australia intersects with linguistic diversity, settlement, and parenting. As a migrant parent in Australia myself, I can relate to the difficulties expressed by the participants. Parenting in a diverse context from one’s upbringing can be a daunting experience, as cultural and linguistic clashes may appear.

The emergence of a hybrid identity for this migrant group seemed to have profoundly helped them with their social inclusion by strengthening their sense of belonging to their local community and easing linguistic barriers. It was interesting to learn that spirituality was not the main reason this group had turned to the church, but it was mostly the need to create linguistically inclusive social networks that would support them. These initial non-spiritual reasons for reaching out to the church highlight the importance of culturally-sensitive migrant services in secular institutions. Government-funded migrant support should aim to fill the linguistic and cultural gaps between migrants and Australian institutions.

This study also evidences the contrast between these churches and secular institutions in Australia, which tend to be overwhelmingly monolingual spaces despite serving a linguistically diverse population. The Australian schooling system primarily seeks to mainstream bilingual or multilingual children into an English-only education at the expense of their heritage language.

Thank you, Ana, for the succinct summary! You could have added a little plug for our forthcoming joint research that demonstrates just how wide the gulf between multilingual parents and monolingual schools is … watch this space! 🙂

The arrival trauma is actually very common in the migration process. Especially for refugees and asylum seekers. As is the downwards occupational mobility. The integration process and inclusion is much easier if the country of origin and the host country have the same language and cultural profile. However, that is not usually the case. The church has provided an essential role in integrating migrants into a new system while still partially holding the same social and cultural values. States are searching for certain type of migrants(usually job profiles that are missing in the labour market currently) but don’t plan for long-term migrations. When I think about people from my country living abroad, it’s mostly a story of the migrants communities making network support groups themselves and new people building upon it. The Chinese migrants in Australia have found a base in which to connect their conservative views and communal ones in the current liberal and individualistic system. But how does the Australian system treat them? The next generation is moving away from such a hybrid identity and with better technology and communication possibilities, would such a way become obsolete? Also, if we would to make better integration and inclusion policies, what would be the first institution to implement them? We still live in world that propagates negative stances on migration and migrants, would a further change in the system be possible?

I think this is an interesting topic and would love to learn more about the ways different groups integrate.

Thank you, Ivana! You raise many interesting questions. Co-ethnic social networks can, of course, be incredibly helpful and provide much-needed settlement support. However, they can also be a source of misinformation and limiting advice, particularly when it comes to newer migrant groups, as another PhD study in our team found:

Williams Tetteh, Vera. (2015). Language, education and settlement: A sociolinguistic ethnography on, with, and for Africans in Australia. (PhD), Macquarie University, Sydney. Retrieved from http://languageonthemove.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Final-PhD-thesis_Vera-Williams-Tetteh.pdf

How migrants are treated and whether they are imagined as forever-outsiders or on a trajectory to belonging is another complex question. Australia certainly privileges white and particularly Anglo identities but, at the same time, has espoused a skilled migration program and multicultural policies since the 1980s. In contrast to Europe, there is a migrant middle class in Australia.

Colic-Peisker, Val. (2011). A New Era in Australian Multiculturalism? From Working-Class “Ethnics” To a “Multicultural Middle-Class”. International Migration Review, 45(3), 562-587. doi:10.1111/j.1747-7379.2011.00858.x

Thank you for this very interesting piece. While most of the participants are (at least) bilingual and ascribe the possibility of having access to multiple languages at their churches as one of the key elements during their transformation (if I understood correctly), all of their children have a relatively low proficiency in Chinese. Without knowing what „low proficiency“ in this case really means, I would have thought that it might be important for the participants that their children can engage with their church community and respective offers both in English and Chinese.

The renegotiation of beliefs and gender roles seem very extreme (from an outward viewpoint), I wonder if the churches are offering strong support in the form of homosocial (solidarity) networks? That might make the renegotiation of the women’s gender roles seem less drastic.

The recognition of foreign certificates along with initial settlement support and a monolingual habitus are issues migrants in Germany are surely facing as well.

Are there currently any follow-up studies or expansions planned on this topic?

Thank you, JJ! Low proficiency can mean many things, of course, but it is the most common heritage language outcome in the second generation in many destination countries and across many origin groups. Even if parents want their children to be bilingual, as they often do, this can be easier said than done.

You can learn more about Chinese heritage language maintenance in Yining’s PhD study:

Wang, Yining. (2020). The heritage language maintenance of Chinese migrant children and their families. (PhD), Macquarie University, Retrieved from http://minerva.mq.edu.au:8080/vital/access/manager/Repository/mq:71673

A more detailed examination of the conflict between parental desires and children’s bilingual learning outcomes can be found here:

Piller, Ingrid, & Gerber, Livia. (2021). Family language policy between the bilingual advantage and the monolingual mindset. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 24(5), 622-635. doi:10.1080/13670050.2018.1503227

After reading this blog post and the research paper from which it is derived, I started to think about analogous settings where we might witness elements of the principal themes explored here. In Australia, where sport is arguably accepted as the national religion, I wondered whether athletic organisations could serve comparable purposes. For instance, I considered whether taekwondo clubs might provide similar support networks. A search for these organisations in Melbourne, where I am based, unveiled examples such as Joon No’s Taekwondo, whose website states that the slogan for the school, and the founder’s philosophy, is “Be the one who contributes to society through moral cultivation” (https://www.jntkd.com.au/about-us.html). One of the club’s offerings is the Universe Family Taekwondo class, with the description that “partaking…as a family ensures fun, quality time spent together….Classes focus on giving respect, teamwork and cooperation. They are a great way to celebrate being a family unit, to learn new things together…” When viewed through the lens that taekwondo acts as a symbol of Korean national identity (Forrest & Forrest-Blincoe, 2018), and that the sport also contains aspects of spirituality (Tuckett, 2018), we anticipate the possibility of the intersection amongst bilingualism, migrant integration, first/second-generation cultural clash resolution and promoting traditional origin-country values in their new nation home environment.

References:

Forrest, J., & Forrest-Blincoe, B. (2018). Kim Chi, K-Pop, and Taekwondo: The Nationalization of South Korean Martial Arts. Ido Movement for Culture. Journal of Martial Arts Anthropology, 18(2), 1-14. dx.doi.org/10.14589/ido.18.2.1

Tuckett, J. (2018). Taekwondo: From National Pursuit to Private Spirituality. Alternative Spirituality and Religion Review, 9(2), 220-245. https://doi.org/10.5840/asrr2018111354

Thank you, Pete! Good point that sports clubs provide comparable integration support. You might enjoy this sociolinguistic ethnographic study of language and identity in a diverse taekwondo club in Copenhagen:

Madsen, Lian Malai. (2015). Fighters, girls and other identities: Sociolinguistics in a Martial Arts Club. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

What a fascinating research topic! It would be interesting to hear how the 2nd generation experiences their integration into society. Have you had a chance to talk to them as well?

I’m a bit puzzled by the conclusion though that successful integration came by the price of conversion. Did any of the participants express regret over their conversion to Christianity or experience their new faith as something negative? Did they feel forced to convert in order to share in the church fellowship and receive this practical help?

I can see a danger in trying to replace church with state. It certainly proved to be a terrible endeavour during Nazi-Germany and also the GDR regime.

I’m sorry if I jumped to the wrong conclusion from what I heard in your presentation. Maybe it’s my upbringing in Germany that causes all my alarm bells to set off. I’d love to hear your take on this.

Thank you, Catharina! Yining did talk to many of the children, too, but not about religion. The families were part of a study about heritage language maintenance and learning, and you can access the complete PhD thesis here: http://minerva.mq.edu.au:8080/vital/access/manager/Repository/mq:71673

Re the conclusion, we are not questioning the participants’ life choices but rather the fact the such settlement support is not really available outside churches. What we were trying to say is that – in a migrant society committed to multiculturalism – everyone should be supported to build new networks and have inclusive pathways towards reestablishing themselves available to them, irrespective of their faith.

Interesting research! The role of the religious community in Chinese migrants social insertion you described is similar to that of Haitians migrants in Brazil. It seems that churches have been operating as effective social agents in the welcoming of migrants worldwide. As I understand it, cultural hybridization is not a one-way process. It is a result of interaction among different cultures. As you pointed in your text when describing the participants’ perception of western parenting, I also understand that cultures (or set of beliefs, in this case) are not equally valued and that the women negotiated which chinese social practices they would keep and which they would rather change for a christian and westernized one. After reading the full research I caught myself wondering if and how the Australians in the church perceived the hybridization process you described. Did Australians also make this movement towards becoming hybrid?

Good question! For this project we only spoke to Chinese converts but in other projects we have often seen that churches can we very inclusive and diverse spaces. Some congregations have a strong social justice ethos and may be dedicated to refugee support or similar endeavors.

Thank you for reading and I hope you are enjoying the summer school! 😊

This is very interesting and I’m glad you two now have a whole chapter about it! But this belief that “western” people without (evangelical) Christian beliefs are immoral and that such children are prone to drug addiction etc, seems really problematic. In my view, the failure to appreciate the morality and humanity of people from different belief systems, and instead stereotype them as immoral dangers to society, is a social ill, whoever it comes from.

Thanks, Alex! Of course, it’s problematic! That’s why we need accessible and trusted communication channels between schools and (NESB) parents. In the absence of such accessible and trusted channels, misinformation and stereotypes will thrive; in the same way that misinformation and disinformation about vaccines fills the void left by the lack of a clear vaccination communication strategy …

What an interesting piece of research! As a migrant myself, I have not considered religion or religious institutes as a go-to place for assistance. In my view, people’s experience with religion pre-migration might be an influencing factor whether they might seek help in religion or through religion post-migration. That’s why, I believe, the nationality of the migrants might totally change the results of this research or at least, the migration experience with religion. Regardless of my comment, this is an intriguing topic for research. Well done!

Thank you, Ellie! Definitely very different for different origin groups; also for different faiths. All our participants turned to evangelical and Pentecostal congregations.