Editor’s note: The Covid-19 pandemic has brought the persistent health disadvantage of Indigenous populations into focus, as well as the exclusion of Indigenous languages from public health communication. In this latest contribution to our series of language aspects of the COVID-19 crisis, Gregory Haimovich and Herlinda Márquez Mora report on an ongoing project that aims to provide bilingual services in Nahuatl and Spanish in rural Mexico. The call for contributions to the series continues to be open.

***

San Miguel Tenango

There can be no question about the crucial role that good quality communication plays in health care. Clearly, the aim of any responsible health care provider is to offer services of a high standard even when multilingual and multicultural settings may present challenges to mutual understanding between doctors and patients. Hence, for years, research in social medicine has been addressing linguistic diversity mostly from the perspective of obstacles that it created for effective health care. Practical, day-to-day considerations still make health professionals focus on ‘overcoming’ or ‘removing’ language barriers rather than view language as a value in itself.

Indigenous minoritized groups worldwide are known to have a worse health profile than majority populations, and they also tend to lose their languages in favor of the languages of majority. The main source of both problems is centuries-long, institutionalized marginalization of Indigenous peoples in the countries where they dwell. Such is the case of Mexico, a country that still counts 67 living Indigenous languages although all of them are in decline.

In Mexico, as elsewhere, Indigenous languages are heavily underrepresented in health care. There are no government-sponsored medical interpreting services in Indigenous languages despite the fact that there are still many citizens that need them – especially elderly persons who have little or no command of Spanish. Medical workers, doctors and nurses alike, are not trained in cultural competence before going to work in predominantly Indigenous communities, nor are they required or even encouraged to learn the languages spoken there.

In San Miguel Tenango, a Nahuatl-speaking community in the northern part of Puebla state, a clinic, or Centro de Salud (‘Health Center’), was established 35 years ago. Although it provides services that are in great demand there, contact with clinic employees has remained very complicated and, on many occasions, painful. Until recently, discrimination against patients and obvious disdain for their culture and traditions on the part of medical personnel has unfortunately been commonplace. And barely any medical worker assigned to the Tenango clinic by the state department of health could speak any Nahuatl.

The older generation of Tenango residents, who have little proficiency in Spanish, have to rely solely on the assistance of their younger, bilingual relatives and friends when they need to go to the clinic. But the presence of such ad hoc interpreters, however helpful, conceals the fact that elderly patients will almost always omit important details that they are embarrassed to share. This risk increases even more when a medical worker, seeing that such a patient comes unaccompanied, picks any random person in sight and asks them to interpret. To prevent such cases, old people who live on their own try to organize chains of assistance between themselves, so that one who speaks better Spanish can help a number of her neighbors in case of necessity.

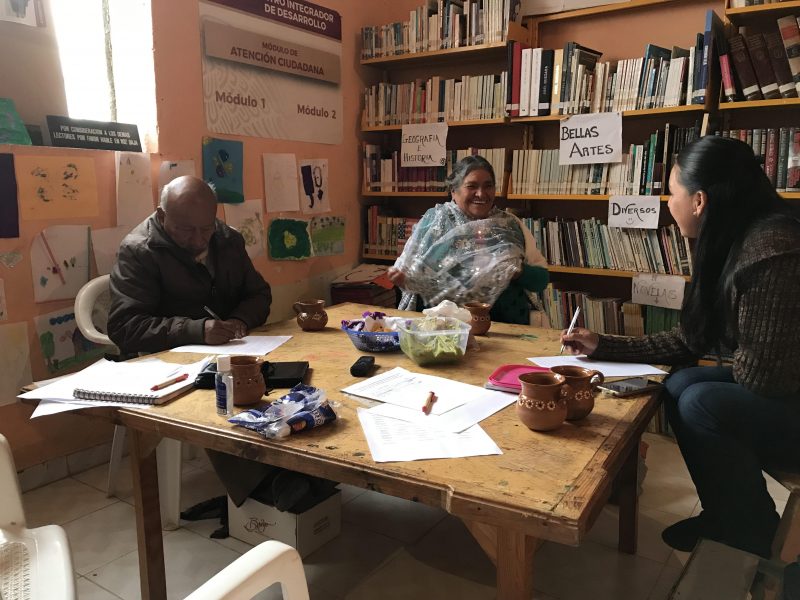

At the terminology workshop

Another problem is that even fairly bilingual residents come into difficulties when they have to translate biomedical discourse, full of specialized terminology and unfamiliar concepts, from Spanish to Nahuatl. Not every medic has been sensitive enough to assess the gap – social, cultural, and educational – between them and the population they serve. Thus, rarely enough effort has been made to ensure that the patients understand the doctor’s words correctly.

At some point health authorities established a position of ‘health educator’ in rural communities, whose duty was to organize informational meetings with the residents. More than that, the attendance of these meetings was made obligatory for persons who receive government assistance for the poor. But in Tenango all such meetings have been conducted in Spanish by a person from outside the community, and old Nahuatl speakers, who were required to show up and sit there until the end, could hardly understand a word.

Such disregard on the part of health authorities and employees could not but lead to a lack of trust towards public health services in Tenango. Even in cases when a member of the clinic’s personnel managed to build a bond with the community, they could be reassigned to another clinic at any moment, without consulting the residents in any form. For the public health system, the people of Tenango have been no more than numb recipients of services and their language has been treated as if it was non-existent.

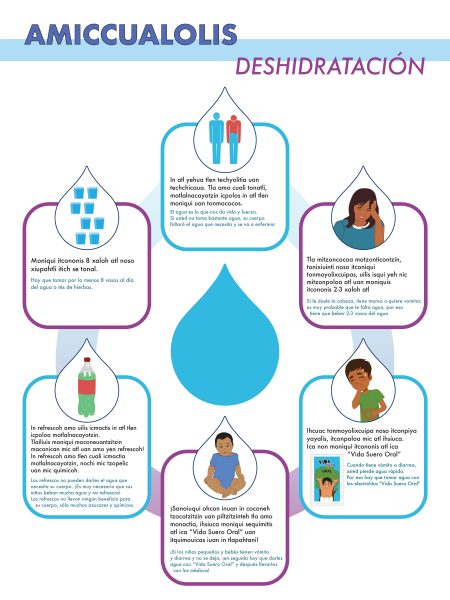

Bilingual poster about dehydration

Talking with the residents, we realized how little it would actually take in terms of language in order to make people feel welcome on their visit to the clinic. And yet, even basic accommodations were rarely done, even in case that did not even involve any knowledge of Nahuatl. For example, doctors who worked in Tenango used to address any patient, irrespective of their age, with tú and not with usted, which is a more polite form of address in Spanish. In Tenango, however, politeness traditionally plays a crucial role in communication. In Nahuatl, the honorific prefix -on- in a verb is almost obligatory when you are talking to an adult, and this manner of speech has also influenced the way of how the local population speaks Spanish. Even using more formal language in Spanish could go some way to make patients feel respected.

The people of Tenango do not really expect that the employees of the health center would start to learn and speak Nahuatl with them, oh no. “But”, they were telling us, “even a greeting in the language would suffice”: that simple tzinōn that you can hear anywhere you go through the green hills of this sprawling community.

This situation inspired us to launch a participatory action research project, focused on the introduction of the Nahuatl language into the work of local health services. Our main aims were, on the one hand, to enhance the prestige and functional utility of Nahuatl, and, on the other hand, to improve health communication and health literacy in Tenango and neighboring villages. We have managed to involve in this project both locals who were eager to contribute to the well-being of their community and the personnel of the health center. As an active group, we hold regular meetings where we discuss vital health issues, trying to solve misunderstandings that have long festered between medical personnel and villagers.

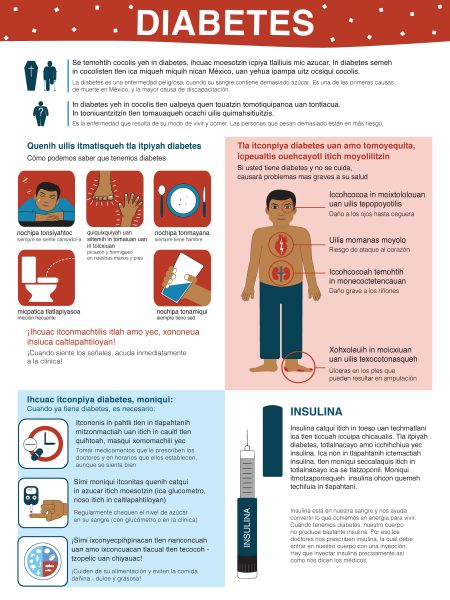

Our first practical step was the development and production of bilingual Nahuatl-Spanish educational posters that tackled the most acute health issues in the community: diabetes type 2, dehydration, healthy nutrition, and high blood pressure. After discussing the content of the posters with the doctors, we then worked on the Nahuatl text and carefully tested it with as many speakers as possible before preparing the final version and the design.

We were well aware that the majority of elderly patients in Tenango could not read or write, but it was important to make Nahuatl visible in the clinic for the first time. Then we could proceed to the creation of audio materials.

Bilingual poster about diabetes

That symbolic appearance of Nahuatl in the local health center provoked a lot of interest among the residents, including young people, who started to take photos of the posters and disseminate them on social networks. Some older visitors noted that it would also be good to make signs in the clinic bilingual, and we happily included this task into our project. Medical personnel, in their turn, started asking us to translate other informational materials into Nahuatl, such as questionnaires distributed by the regional department of health.

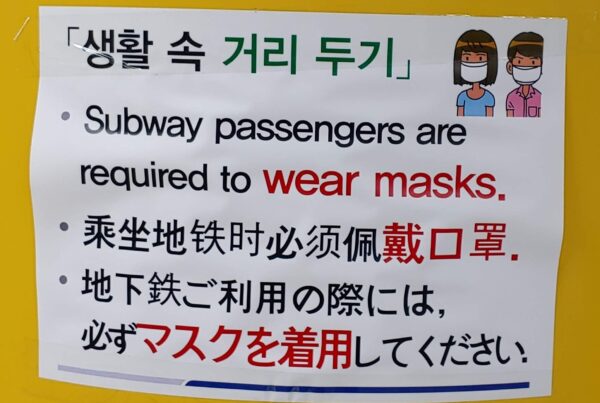

The outbreak of Covid-19 seemed to bring our project to a halt but, in fact, also provided us with new opportunities. Although we both happened to be far from Mexico when the pandemic was declared, we decided to produce an informational video about the coronavirus and precautions against it in the variety of Nahuatl spoken in Tenango. At that moment, the virus had only recently emerged in Mexico and hardly any measures had been taken to curb its spread. But the inhabitants of Tenango were excited about the video, and it got shared by tens of people and seen hundreds of times just in a few days. Two weeks later, when certain anti-coronavirus measures had come into force, the village council asked us to produce another video in Nahuatl, with updated information, which we gladly did.

In addition, Herlinda recorded an informational audio message, which was then played in communal gatherings and from a loudspeaker attached to a truck belonging to the council, making the warnings heard across the whole village.

Nothing of this sort had ever been done in this region by health authorities. For the first time, health information in Tenango was given a Nahuatl voice, but even more importantly, it was a voice that many villagers easily recognized – it was one of their own voices. The impact of these innovations is yet to be assessed, but the demand for them and the impression they have had on the community already tell a great deal.

We can only hope that the current pandemic will make health authorities in Mexico – and in linguistically diverse societies around the globe – rethink their attitudes and policies towards Indigenous people, giving Indigenous languages and their speakers an adequate role in the services provided for the communities where these languages are spoken. There is a growing awareness of the importance of language-centered approach to health. As for now, we represent only a small community project, but we also want to set an example of how things can be changed and how a healthier language can also improve societal health.

Reference

A longer account of the study of communication in health services in Sierra Norte de Puebla will be published in Multilingua shortly.

Language challenges of the Covid-19 pandemic

Visit here for our full coverage of language aspects of the COVID-19 crisis.

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a

Thank you, Gregory and Herlinda, for delivering such an informative and useful article. Thanks to your information, it is more evident to me how unprivileged and disequality the Indigenous people inhabiting in deprived regions, particularly in San Miguel Tenango, have to encounter with healthcare services during the aftermath of the COVID-19. In this state of mind, I am in the same vein with you that the Mexican government should implement some viable strategies to alleviate the insufficient bilingual resources of healthcare services for the dweller in not only San Miguel Tenango but also in other regions. This is primarily because language is supposed to be the tool to unify people not widen the inequity gap.

Thank you! The paper is going to be published very soon as far as I know.

I wouldn’t say that in our case the indigenous population is somehow “forced” to use the traditional medicine, because there is still a kind of medical pluralism existing in Tenango. Indigenous medicinal knowledge and practices are not so vigorous as before, but with certain issues many people still prefer to go to traditional healers than to the clinic.

Hope I can get to read the longer version on Multilingua soon!

I read about how Nahuatl associate honorifics with the tradition/us and reversely Spanish address terms with rudeness/them. Given such iconised linkage it must be more important to understand this and many other seemingly minute cultural differences and perceptions.

Probably the intimidating experience in hospitals also force indigenous people to resort to the traditional local doctors and healers in many places.