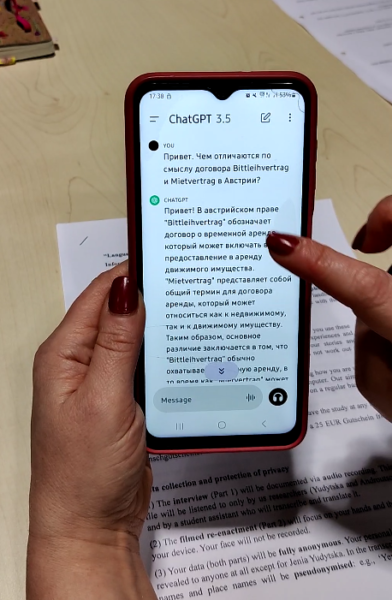

Ukrainian migrant asking ChatGPT to explain different types of rental contracts in Austria (still from Yudytska & Androutsopoulos 2025)

For nearly four years now, I’ve been heavily involved in online (Telegram-based) communities for Ukrainian forced migrants in Austria. Such communities sprang up all across Europe after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in early 2022, serving as grassroots digital info-points. In those early, chaotic days, the groups focused on a Ukrainian’s first steps upon getting off the train in their new country. They have since expanded to cover everything from where to buy buckwheat (a very pressing question!) to the fine details of the local education system, health insurance, job market, etc.

The communities are run for Ukrainian refugees, by Ukrainian- and Russian-speakers, that is, overwhelmingly by migrants – forced, labour, student; first-gen, second-gen; etc. It truly is mutual aid: those who migrated earlier answer questions on integration, those who left recently give tips on how best to reach relatives in occupied territory. My family left in 1999, when I was five; I co-admin one group for Ukrainians in my home state of Upper Austria (ca. 3,700 members) and one group focused on how to change from the Temporary Protection status to a longer-term work/residence permit (ca. 8,300 members), plus I occasionally help out in other groups.

In 2025, our communities gained one more, less welcome, “member”: ChatGPT.

Migrants’ search for information

Understanding the role of ChatGPT in these communities requires understanding the complex informational space newly arrived migrants are in. There is an avalanche of info to take in. Some involves the everyday differences: when your child has a fever, at what temperature can you call the ambulance without getting in trouble for wasting their time? Other aspects are specific to the (forced) migrant status, and would stump a local too. Language barriers make accessing information difficult. Even with machine translation, it’s hard to know what term to google or how to interpret a bureaucrat’s answer.

This is where the Telegram communities come in, providing an easy place to ask for help and discuss problems.

An NGO’s German-Ukrainian sign about food and clothing distribution; the understandable but incorrect Ukrainian suggests machine translation (photo taken by author)

Still, they’re not a panacea. Us volunteers learned only on the fly the ins-and-outs of the Austrian asylum system in all its kafkaesque glory: we sometimes misremember, misunderstand, and mistranslate. Grasping a question can take real detective work, especially when there’s a dozen ways to translate a single German term. Official Austrian sources give a lot of information orally; this leads to bewildering discussions where one person informs the chat their social worker said X, another says it was Y, and the third Z. Maybe it’s miscommunication, maybe the official sources have no clue either.

Above everything loom the rumours, best illustrated by the (admittedly pretty sexist) Russian acronym, ОБС – одна бабка сказала, lit. “some old lady said”. It’s used in the sense of, “Uh-huh, riiight, you got that info from your cousin’s friend’s mom’s neighbour”. In 2027 all Ukrainians in the EU will be put on the next train home, even if the war is still ongoing. Truth or ОБС? Great (unanswerable) question!

Enter ChatGPT

Into all this chaos slams the iron certainty of ChatGPT. If it worked as advertised, it would be an invaluable resource for migrants. You ask a question, it searches for and provides a summary of official information. No linguistic barriers, no mistranslations, no complex legalese; no petty online fights to wade through. The appeal is clear.

The only tiny problem is that it doesn’t work as advertised.

The biggest issue is in how ChatGPT functions: it doesn’t search for and copy-paste information from a database, but rather generates a statistically likely sequence of tokens (words) based on the data it was trained on. This is why it can “hallucinate”, that is, make up answers which are linguistically coherent but factually untrue. It has also obviously been fed more data (law databases, official websites, forum discussions, etc.) from Germany than Austria. For example, it has confidently explained to a Ukrainian that she’s legally obligated to have health insurance – true in Germany, not so in Austria.

Linz Castle on the Danube, Upper Austria, lit up in the colours of the Ukrainian flag (photo taken by author)

The AI technique ‘Retrieval Augmented Generation’ (RAG) is meant to resolve this: ChatGPT first searches for and pulls relevant information from a website, then incorporates it into the answer. (ChatGPT uses RAG sometimes, but not constantly. It costs more energy, thus more money.) But the answer is still generated, so hallucination is still possible. This leads to ChatGPT claiming, for example, “According to the City of Vienna website, Ukrainians have to hand in their old refugee ID card. [Link to website]” Except its generated summary missed a negation: the website explicitly states Ukrainians do not have to hand in their old refugee ID card. RAG can thus lead to even greater misinformation, as it implies a direct source.

The other huge problem is the limited information actually available on migrant issues; even if hallucination was somehow solved, the adage of ‘garbage in, garbage out’ for machine learning remains. For example, to switch to a longer-term residence permit requires the migrant to have an ortsübliche Unterkunft (“housing according to local standards”). ChatGPT physically cannot answer what these local standards are. I know this because, according to my old-fashioned research techniques of searching law databases, skimming court cases, and asking lawyer friends, neither can anybody else! Unfortunately, it is too often the case that there is too little concrete info for ChatGPT to be trained on.

In short, using ChatGPT for information is a gamble. Sometimes it works great, sometimes it generates nonsense. To know which is which, the migrant is left with the same problem of surmounting the language barrier they started with.

Mutual aid with and against machines

Rows of donated women’s shoes at SUNUA, a grassroots organisation supporting Ukrainians in Upper Austria, 3 weeks post-invasion (photo taken by author)

I don’t consider myself a techno-pessimist – actually, I rely on language technologies heavily in my online volunteer work. My phone’s autocorrect is a life-saver. While I can read and write in Russian, I left Ukraine before starting formal education, and find it slow and frustrating to spell without autocorrect. Similarly, machine translation is a great help. I occasionally need it to double-check my understanding of more complex Ukrainian-language questions; I also machine translate German-language official updates for the sake of speed, then post-edit the Russian text to correct mistakes and stilted phrasing before posting.

That is, due to my background as a child migrant from a primarily Russian-speaking area of Ukraine, I have varying levels of competencies in the three languages I need: Russian, Ukrainian, German. For all their faults, language technologies are an invaluable resource for stuffing the gaps so I can help people successfully. And efficiently, as this has always been 100% unpaid labour in my free time, next to my full-time uni work.

But all this is why I find the intrusion of ChatGPT into our spaces so infuriating on a personal level. In the midst of a horrible situation, between fear, grieving, trauma, burnout, we’re all trying to use the linguistic and technological resources available to us to help each other. I accept arguing against a community member’s cousin’s friend’s mom’s neighbour’s experience as part of that – that connection is also a resource, and it’s human to trust an acquaintance over a fuzzily written law in a language you don’t speak yet. I’m willing to spend my free time picking apart where the confusion lies.

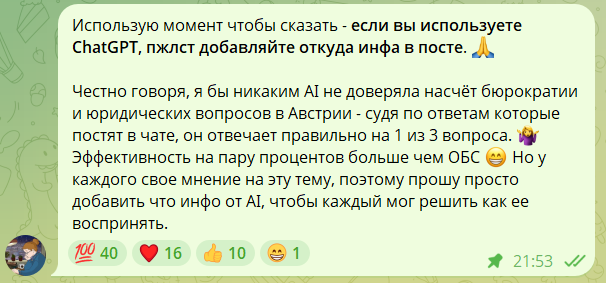

The author’s post in a Telegram group explaining that AI as a source must be clearly stated, with over 60 users leaving reaction emoji of agreement (screenshot taken by author)

I don’t accept arguing with ChatGPT screenshots.

ChatGPT adds beautiful formatting, with eye-catching emoji as bulletpoints. ChatGPT switches between Cyrillic and Latin easily, writing out German acronyms and translating them to Russian in brackets: ÖGK (Österreichische Gesundheitskasse – Австрийская касса медицинского страхования), wow. ChatGPT cites laws using a fancy § paragraph sign I have to copy-paste each time.

Sure, the actual information may or may not be correct, but that’s less important than the style, which so neatly mimics that of official sources. It simply looks trustworthy – the complete opposite of my own messages, written one-handed on a moving bus, with at least one butchered case suffix apiece. It’s unsurprising that people cling to ChatGPT’s information more stubbornly than to the usual ОБС.

Arguing against it is thus extra tedious and, frustratingly, requires me to do additional work. “Wait, no, where did you get that information from, is that an official source?” “Uh, nope, that website ChatGPT cited says the opposite.” “Dude, did you actually read the law ChatGPT ‘references’ – it’s about industrial chemicals, not document translation.” Most unsatisfactorily for all involved, having to prove a negative: “I’m sorry, but there’s no information on that. I don’t know why ChatGPT says there is, maybe it exists for Germany, but not for Austria.”

As a migrant who’s also stared at bureaucratic German in confusion and anxious despair, I don’t blame people for turning to AI. As a volunteer, it’s genuinely made me want to quit: in anger, in exhaustion, with a childishly vindictive, “Well, if they prefer machine over human, so long and thanks for all the fish.”

Where to next?

In principle, the issues explored here are no different from those we’re facing in other areas: education, academia, news, etc. Misinformation is rife everywhere; so is a lack of digital literacy on what current AI can and can’t do. For me, the crucial point is how vulnerable forced migrants are. Misuse of ChatGPT can lead not to a failed homework assignment but to problems on an existential level: with the legal status, with housing, with having enough money for food. Similarly, to put it bluntly, I’m paid to deal with students’ AI use; in volunteer work, it’s just one more weight tipping the scales in favour of finally quitting. It’s also important to add that not all my fellow admins share my worries. Some eagerly embrace ChatGPT answers themselves, which of course save time and energy for volunteers who have little of either to spare.

Our current ‘solution’ is that people must state openly that the information they’re posting is AI-generated. Then other members can decide themselves to what extent they trust it. In this, I would say, we’re ahead of the curve compared to many organisations, and for now, this will have to be enough.

Reference

Yudytska, J. & Androutsopoulos, J. (2025). The use of language technologies in forced migration: An explorative study of Ukrainian women in Austria. In M. Mendes de Oliveira & L. Conti (eds.), Explorations in Digital Interculturality: Language, Culture, and Postdigital Practices (pp. 135-166). Transcript. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783839476291-007

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a

Thank you for this powerful and painfully honest piece, Jenia. As you point out, “the issues explored here are no different from those we’re facing in other areas: education, academia, news, etc. … AI ‘errors’ are not abstract risks but existential ones, while for volunteers they become yet another invisible layer of emotional and cognitive labour.” When teaching an academic writing course, I sense a related tension, in which fleeting ideas and learning opportunities embedded in the revision process of language choices can easily be overshadowed by the authority of AI outputs. A timely and important contribution!

Thank you very much Yixi! I taught a course on language technologies (chatbots, machine translation, etc.) last semester and I’m still ruminating on the students’ input on their own AI use. My main conclusion right now is that simply improving digital literacy on the topic is really important. For example, the fact that ChatGPT *generates* and doesn’t actually “search” for info was quite surprising for most students; their honest surprise in turn made me understand why they trust AI answers in a way I don’t.

Thank you, Jenia; a wonderful piece to read and a powerful reminder to look beyond the fluff of AI-generated texts, and why source checking and talking to humans (when possible) are so important for getting more accurate information. Thank you for the work you do for refugees; it’s so needed.

Ana

Thank you so much Ana! Source checking really is one of those absolutely crucial but extremely difficult everyday issues, in all alreas of life.. A few years ago Germany used to have a project called “Migration Counselling 4.0” where EU workers were offered counselling re labour rights within already existing online communities (https://minor-kontor.de/migration-counselling-4-0/). I think it was a really interesting idea and I wish the EU would really build on it – I would *love* to have a legal professional drop by our Telegram groups once every few months.