UNESCO’s ‘Digital Learning Week’, which focused on AI and the future of education, was held earlier this month, and debates about the role of generative artificial intelligence (GAI) in the classroom have taken centre stage in education policy research. Around the world, educators, school administrators, and government officials are grappling with ethical questions surrounding the use of GAI and related technologies, such as commercial Large Language Models (LLMs), in teaching and learning.

The use of GAI in school poses serious and urgent questions: Should GAI be implemented in schools, and do we have sufficient knowledge about its educational merit (if any)?

Despite the hype, there is little positive evidence that this technology can actually improve student outcomes. But there is plenty of negative evidence that is cause for concern: it may lead to the dehumanization of learning. This is not surprising given that, even in commercial settings, the promise of increased productivity is not being fulfilled.

Still, schools are rushing to adopt GAI despite a wealth of evidence showing that the recent uncritical adoption of mobile phones and social media has in fact been harmful to children’s development. As a society, we are trying to pull back from feeding these technologies to our children. Still, even with these precedents, schools are adopting commercial AI technologies in the classroom uncritically, without fully considering their potential harms.

The challenges of GAI use in education are multifaceted and multilayered, ranging from concerns about ethics and academic integrity to privacy issues related to the ‘datafication’ of learning and childhood, to actual physical threats and harm to students. Beyond the psychosocial and physical harms to children, research has shown that “LLMs exacerbate, rather than alleviate, inequality” in learning, given that a few large corporations control the computation infrastructures on which these models run. So, against this background, what does Australian policy state regarding GAI in education?

In Australia, the latest guiding framework for the use of GAI in education is the ‘Australian Framework for Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Schools’ (The Framework). Developed by the Federal Government in partnership with states, territories, and other regulatory bodies such as the Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA), The Framework aims to define what “safe, ethical and responsible use of generative AI should look like to support better school outcomes” (p. 3).

As a guiding principle, The Framework highlights that critical thinking must be at the forefront of GAI use in schools, and that GAI should not replace or restrict human thought and experience.

However, what does it mean to use GAI “critically”? The research is clear that the regular use of GAI in learning quickly leads to over-reliance, which negatively affects cognitive abilities. Arguing that critically engaging with AI means empowering students to evaluate the machine’s output for themselves is similar to suggesting that we should teach students incorrect content and then ask them to form their own opinions.

The promise of GAI in education is that it will enable personalized learning. Unfortunately, machine-based ‘personalized learning’ forgoes the human-centered approach needed for a successful education. Instead, it relies on the datafication of students through continuous monitoring and surveillance. This shift in educational policy has sparked debate within academic circles about issues such as student privacy and safety, the ‘datafication’ of childhood, and how children’s data harvesting is used to shape their futures, effectively turning students into ‘algorithmic ensembles’.

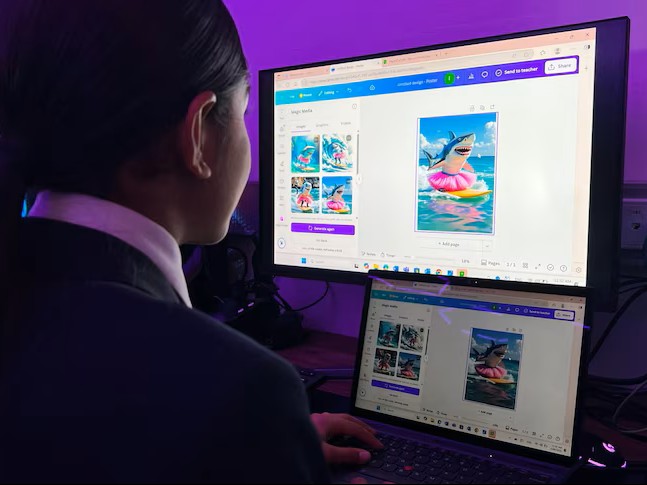

Despite these real dangers, the latest iteration of the Australian school curriculum has explicitly incorporated GAI into the curriculum, supporting its use for whole school planning and providing teachers with the option of content elaboration using GAI (Australian Government Department of Education, 2025). The incorporation of GAI into the curriculum raises safety and welfare concerns for children, as they could be exposed to harmful materials and dangerous interactions, and a recent tragedy has brought to the surface the dark side of this technology. This heartbreaking case highlights that this technology may not be suitable for children, given their vulnerability to certain features of GAI, such as agreeability and dependence, which are design features aimed at engineering addiction. These technologies are still in their experimental stages, and we know little about the effects they may have on developing brains.

The premature and uncritical adoption of GAI in schools rings a too-familiar note to the uncritical adoption of social media in youth, which many governments around the globe are now trying to reverse, including Australia.

Vague policies that encourage the use of AI in schooling mean that teachers and schools are using the tool without a clear evidence base, in inconsistent ways, and without obtaining full parental consent. In my PhD research, I found that parents often resent the amount of technology schools use for education, and I also discovered that these technologies follow students home, encroaching on their private lives. Schools are taking away the parental prerogative of deciding when and how they introduce technologies such as GAI to their children, forcing them down a path they might prefer their children not to go.

Overall, the “critical” use of GAI in education must mean that rejection of GAI is an option. An option that is increasingly precluded by the headlong rush into the GAI hype.

Related content from our podcast

- Episode 57: The Social Impact of Automating Translation: Tazin Abdullah in conversation with Ester Monzó-Nebot (03/08/2025)

- Episode 55: Improving quality of care for patients with limited English: Brynn Quick in conversation with Leah Karliner (26/06/2025)

- Episode 50: Researching language and digital communication: Brynn Quick in conversation with Christian Ilbury (22/04/2025)

- Episode 46: Intercultural competence in the digital age: Brynn Quick in conversation with Amy McHugh (12/03/2025)

- Episode 41: Why teachers turn to AI: Brynn Quick in conversation with Sue Ollerhead (09/01/2025)

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a