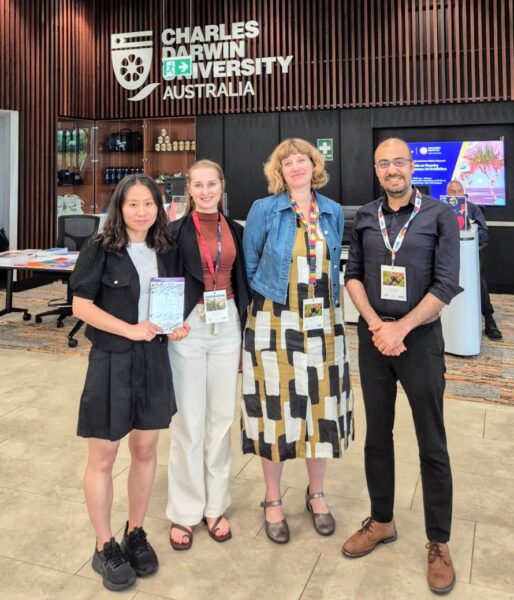

The team behind the Language-on-the-Move Podcast (Image credit: Language on the Move)

Final piece of good news for the year before we head into a publishing break over January: we’ve just heard that the Language-on-the-Move Podcast has won the 2025 Talkley Award

The Talkley Award is issued by the Australian Linguistic Society (ALS) and “celebrates the best piece or collection of linguistics communication produced in the previous year by current ALS members. The Award acknowledges that the discipline of linguistics needs champions to promote linguistics in the public sphere and explain how linguistic evidence can be used to solve real-life language problems.”

This is a wonderful end-of-year present for our team in recognition of the work and care we’re putting into creating the podcast. Special thanks and congratulations also to our podcast publishing partner, the New Books Network.

After the 2012 Talkley Award went to Ingrid Piller for the Language on the Move website, this is the second time the award goes to our team – an amazing recognition of the long-term impact Language on the Move has had on public communications about linguistic diversity and social justice.

Thank you to all our supporters who nominated us for the award! Special thanks to Dr Yixi (Isabella) Qiu and her students in the Guohao College Future Technology Program at Tongji University. After using the Language-on-the-Move Podcast as a learning resource, they have been among our biggest fans

To celebrate with us, listen to an episode today! You an find your list of choice below.

As always, please support us by subscribing to the Language on the Move Podcast on your podcast app of choice, leaving a 5-star review, and recommending the Language on the Move Podcast and our partner the New Books Network to your students, colleagues, and friends.

Students of the Guohao College Future Technology Program at Tongji University in Shanghai are among the fans of the Language-on-the-Move Podcast (Image credit: Dr Yixi (Isabella) Qiu)

List of episodes to date

- Episode 64: Your Languages are your superpower! Agnes Bodis in conversation with Cindy Valdez (17/11/2025)

- Episode 63: Australia’s National Indigenous Languages Survey: Alexandra Grey in conversation with Zoe Avery (28/10/2025)

- Episode 62: Migration is about every human challenge you can have: Brynn Quick in conversation with Shaun Tan (17/09/2025)

- Episode 61: Cold Rush: Ingrid Piller in conversation with Sari Pietikainen (09/09/2025)

- Episode 60: Sexual predation and English language teaching: Hanna Torsh in conversation with Vaughan Rapatahana (02/09/2025)

- Episode 59: Intercultural Communication – Now in the 3rd edition: Loy Lising in conversation with Ingrid Piller (26/08/2025)

- Episode 58: Erased voices and unspoken heritage: Alexandra Grey in conversation with Zozan Balci (20/08/2025)

- Episode 57: The Social Impact of Automating Translation: Tazin Abdullah in conversation with Ester Monzó-Nebot (03/08/2025)

- Episode 56: Multilingual practices and monolingual mindsets: Brynn Quick in conversation with Jinhyun Cho (18/07/2025)

- Episode 55: Improving quality of care for patients with limited English: Brynn Quick in conversation with Leah Karliner (26/06/2025)

- Episode 54: Chinese in Qatar: Tazin Abdullah in conversation with Sara Hillman (19/06/2025)

- Episode 53: Accents, complex identities, and politics: Brynn Quick in conversation with Nicole Holliday (12/06/2025)

- Episode 52: Is beach safety signage fit for purpose? Agnes Bodis in conversation with Masaki Shibata (05/06/2025)

- Episode 51: The case for ASL instruction for hearing heritage signers: Emily Pacheco in conversation with Su Kyong Isakson (28/04/2025)

- Episode 50: Researching language and digital communication: Brynn Quick in conversation with Christian Ilbury (22/04/2025)

- Episode 49: Gestures and emblems: Brynn Quick in conversation with Lauren Gawne (14/04/2025)

- Episode 48: Lingua Napoletana and language oppression: Tazin Abdullah in conversation with Massimiliano Canzanella (07/04/2025)

- Episode 47: Teaching international students: Brynn Quick in conversation with Agnes Bodis and Jing Fan (31/03/2025)

- Episode 46: Intercultural competence in the digital age: Brynn Quick in conversation with Amy McHugh (12/03/2025)

- Episode 45: How does multilingual law-making work: Alexandra Grey in conversation with Karen McAuliffe (05/03/2025)

- Episode 44: Educational inequality in Fijian higher education: Hanna Torsh in conversation with Prashneel Goundar (25/02/2025)

- Episode 43: Multilingual crisis communication: Tazin Abdullah in conversation with Li Jia (22/01/2025)

- Episode 42: Politics of language oppression in Tibet: Tazin Abdullah in conversation with Gerald Roche (14/01/2025)

- Episode 41: Why teachers turn to AI: Brynn Quick in conversation with Sue Ollerhead (09/01/2025)

- Episode 40: Language Rights in a Changing China: Brynn Quick in conversation with Alexandra Grey (01/01/2025)

- Episode 39: Whiteness, Accents, and Children’s Media: Brynn Quick in conversation with Laura Smith-Khan (24/12/2024)

- Episode 38: Creaky Voice in Australian English: Brynn Quick in conversation with Hannah White (18/12/2024)

- Episode 37: Supporting multilingual families to engage with schools: Agi Bodis in conversation with Margaret Kettle (20/11/2024)

- Episode 36: Linguistic diversity as a bureaucratic challenge: Ingrid Piller in conversation with Clara Holzinger (17/11/2024)

- Episode 35: Judging refugees: Laura Smith-Khan in conversation with Anthea Vogl (02/11/2024)

- Episode 34: How did Arabic get on that sign? Tazin Abdullah in conversation with Rizwan Ahmad (30/10/2024)

- Episode 33: Migration, constraints and suffering: Ingrid Piller in conversation with Marco Santello (14/10/2024)

- Episode 32: Living together across borders: Hanna Torsh in conversation with Lynnette Arnold (07/10/2024)

- Episode 31: Police first responders interacting with domestic violence victims: Tazin Abdullah in conversation with Kate Steel (29/09/2024)

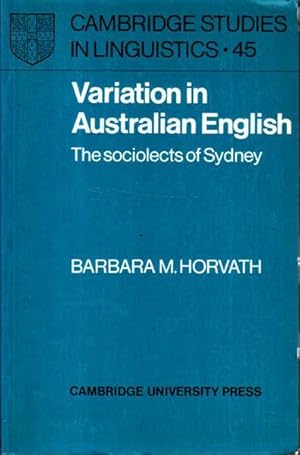

- Episode 30: Remembering Barbara Horvath: Livia Gerber in conversation with Barbara Horvath (10/09/2024)

- Episode 29: English Language Ideologies in Korea: Brynn Quick in conversation with Jinhyun Cho (08/09/2024)

- Episode 28: Sign Language Brokering: Emily Pacheco in conversation with Jemina Napier (30/07/2024)

- Episode 27: Muslim Literacies in China: Tazin Abdullah in conversation with Ibrar Bhatt (24/07/2024)

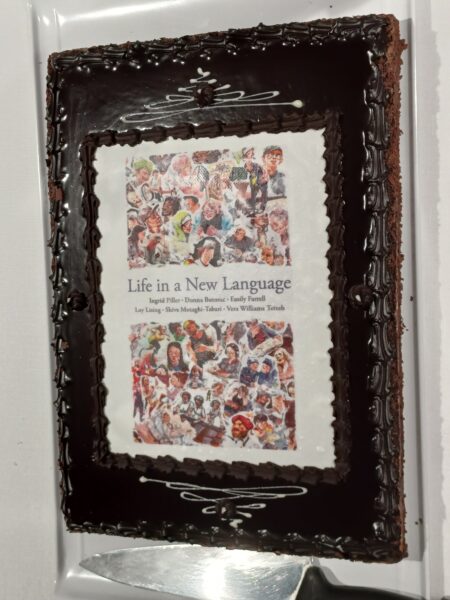

- Episode 26: Life in a New Language, Pt 6 – Citizenship: Brynn Quick in conversation with Emily Farrell (17/07/2024)

- Episode 25: Life in a New Language, Pt 5 – Monolingual Mindset: Brynn Quick in conversation with Loy Lising (11/07/2024)

- Episode 24: Language policy at an abortion clinic: Brynn Quick in conversation with Ella van Hest (05/07/2024)

- Episode 23: Life in a New Language, Pt 4 – Parenting: Brynn Quick in conversation with Shiva Motaghi-Tabari (03/07/2024)

- Episode 22: Life in a New Language, Pt 3 – African migrants: Brynn Quick in conversation with Vera Williams Tetteh (27/06/2024)

- Episode 21: Life in a New Language, Pt 2 –Work: Brynn Quick in conversation with Ingrid Piller (19/06/2024)

- Episode 20: Life in a New Language, Pt 1 – Identities: Brynn Quick in conversation with Donna Butorac (12/06/2024)

- Episode 19: Because Internet: Brynn Quick in conversation with Gretchen McCulloch (03/06/2024)

- Episode 18: Between Deaf and hearing cultures: Emily Pacheco in conversation with Jessica Kirkness (01/06/2024)

- Episode 17: The Rise of English: Ingrid Piller in conversation with Rosemary Salomone (21/05/2024)

- Episode 16: Community Languages Schools Transforming Education: Hanna Torsh in conversation with Joe Lo Bianco (07/05/2024)

- Episode 15: Shanghai Multilingualism Alliance: Yixi (Isabella) Qiu in conversation with Yongyan Zheng (02/05/2024)

- Episode 14: Multilingual Commanding Urgency from Garbage to COVID-19: Brynn Quick in conversation with Michael Chestnut (27/04/2024)

- Episode 13: Making sense of “Bad English:” Brynn Quick in conversation with Elizabeth Peterson (13/04/2024)

- Episode 12: History of Modern Linguistics: Ingrid Piller in conversation with James McElvenny (10/04/2024)

- Episode 11: 40 Years of Croatian Studies at Macquarie University: Ingrid Piller in conversation with Jasna Novak Milić (08/04/2024

- Episode 10: Reducing Barriers to Language Assistance in Hospital: Brynn Quick in conversation with Erin Mulpur, Houston Methodist Hospital (26/03/2024)

- Episode 9: Interpreting service provision is good value for money. Ingrid Piller in conversation with Jim Hlavac (19/03/2024)

- Episode 8: What does it mean to govern a multilingual society well? Hanna Torsh in conversation with Alexandra Grey (22/02/2024)

- Episode 7: What can Australian Message Sticks teach us about literacy? Ingrid Piller in conversation with Piers Kelly (21/02/2024; originally published 2020)

- Episode 6: How to teach TESOL ethically in an English-dominant world. Carla Chamberlin and Mak Khan in conversation with Ingrid Piller (20/02/2024; originally published 2020)

- Episode 5: Can we ever unthink linguistic nationalism? Ingrid Piller in conversation with Aneta Pavlenko (19/02/2024; originally published 2021)

- Episode 4: Language makes the place. Ingrid Piller in conversation with Adam Jaworski (18/02/2024; originally published 2022)

- Episode 3: Linguistic diversity in education: Hanna Torsh in conversation with Ingrid Gogolin (17/02/2024; originally published 2023)

- Episode 2: Translanguaging: Loy Lising in conversation with Ofelia García (16/02/2024; originally published 2023)

- Episode 1: Lies we tell ourselves about multilingualism. Ingrid Piller in conversation with Aneta Pavlenko (15/02/2024)

Group photo of all awards recipients at ALAA Conference 2025 (Image credit: ALAA)

Recently, I had the opportunity to attend the 2025 Applied Linguistics Association of Australia (ALAA) Conference, held at Charles Darwin University in Garramilla/Darwin on Larrakia Country from November 17-19. The conference was devoted to the topic ‘Language and the Interface of Mono-, Multi-, and Translingual Mindsets’ and brought together Australian and international scholars.

The 3-day conference in a tropical setting offered many inspiring and new experiences and an excellent platform for networking, collaboration and the exchange of ideas.

Inspiring Keynotes

Keynote lectures delivered by Shoshana Dreyfus (University of Wollongong) and Robyn Ober (Batchelor Institute) left a great impression on me.

Shoshana spoke about linguistic strategies in activism. She presented a positive discourse analysis unraveling effective activist discourse in letters to the minister. Based on such a letter she had written herself, her talk showed how activists rally support. Her compassionate talk shed light on different registers to make change and become an ally for non-verbal people.

Robyn introduced the audience to beautiful metaphors of linguistic diversity and exchange in Indigenous Australian education. Her description of “slipping and sliding” between languages gave insights into multilingual practices.

The audience was particularly touched by the metaphor of language as a guitar: just as an instrument with multiple strings produces more melodious and harmonious tunes, multilingual people have more than one string to their bow, which creates greater harmony when joined.

Encountering Indigenous Languages and Cultures

The Macquarie University team at ALAA (Image credit: Sophie Munte)

As a PhD student from the University of Hamburg in Germany who currently spends time at Macquarie University in Sydney as part of my joint PhD degree across the two institutions, the conference offered me the privilege to learn about Indigenous languages and cultures.

Darwin offers a setting where the fact that Australia is Indigenous land is much more palpable than in Sydney. Together with Robyn’s keynote and other talks, this opened my eyes to Australia’s rich diversity of Indigenous cultures and languages.

Presenting my research

The conference provided me with the opportunity to present first results from my PhD research on the governance of parent-school communication in linguistically diverse schools in Hamburg and Sydney.

Employing policy analysis, surveys and interviews, my research explores the use of child language brokering as a way to bridge language barriers between parents and schools. The international comparison will shed light on how institutions in different national contexts deal with their shared responsibility to communicate with parents. Ultimately, the research will contribute to improved policies and teacher training so that all parents can fully participate in the education of their children, regardless of linguistic background.

Grateful to ALAA for the support

Attending the 2025 ALAA conference has been a wonderful opportunity for me. I am particularly grateful for the funding support I received through the ALAA Postgraduate Conference Scholarship. This scholarship, which was awarded to six higher degree research students, including myself, financially supports the conference attendance of HDR researchers.

I also commend the ALAA Higher Degree Research representatives for creating such an inclusive and welcoming event: each evening they organized meet-ups for all HDR candidates at the conference, including a language themed trivia night – all of which helped to establish a supportive community among us HDR students and build connections that will endure beyond the conference.

]]>

The president of University of Hamburg, Prof Dr Hauke Heekeren, welcomes the new members of Ingrid Piller’s Humboldt Professorship Team

Attentive readers will remember that in May this year we advertised six doctoral and postdoctoral positions to conduct research related to “Linguistic Diversity and Social Participation across the Lifespan” in the Literacy in Diversity Settings (LiDS) Research Center at University of Hamburg, as part of the Alexander-von-Humboldt Professorship awarded to Ingrid Piller.

In response, we received 270 applications. While it was exciting to see that there is so much interest in our work, it was also heart-breaking to have to make so many tough decisions from an amazing pool of highly qualified candidates.

After conducting Zoom and on-campus interviews in July and August, I am now pleased to report that the Dream Team has started their work at the beginning of November. We have six extremely talented and accomplished early career researchers joining the Language-on-the-Move community, and in this post, they are introducing themselves in their own words.

Jenia Yudytska

I’m Jenia Yudytska, a Ukrainian-Austrian postdoc. I did my PhD in computational sociolinguistics at the University of Hamburg, investigating the influence of technological affordances on language in online communication. My current research interest focuses on how migrants use language technologies, particularly machine translation, as a resource in their everyday life. Since 2022, I have also been heavily involved in the organisation of grassroots mutual aid online communities for Ukrainian forced migrants in Austria.

I’m particularly excited for this chance to jump into applied linguistics, and the chance to combine both my love for research and my desire to make a social impact!

Juan Sánchez

¡Hola!

I’m Juan Felipe Sánchez Guzmán, a Colombian student and researcher based in Hamburg. In my home country, I conducted research on gender diversity and language teaching, as well as on the implementation of the Colombian Ministry of Education’s bilingualism programs involving foreign tutors in public institutions within a predominantly monolingual context. Building on my passion for languages, my own migration experience, and those of fellow immigrants, my Master’s research explored the integration of Latinx nurses into the German healthcare system.

I look forward to showcasing through research the values and strengths that multilingual communities bring to education, healthcare, and society as a whole.

Mara Kyrou

My name is Mara Kyrou and I hold an MA degree in Linguistics and Communication from the University of Amsterdam. My Masters research explored language policies, practices and ideologies as perceived by teaching professionals in multilingual non-formal education settings in Greece and the Netherlands. My research interests also include professional and intercultural communication in transnational work contexts, gender theory and theater education. I have also contributed to the design and implementation of language learning programs for students with a (post-)migrant background with international NGOs.

In this research group we are working with (auto-)ethnographies and focusing on globally emerging topics hence we don’t just study things as they are but as we humans are.

Martin Derince

Roj baş!

I am Martin Serif Derince. I carried out my PhD research on Kurdish heritage language education in Germany at the University of Potsdam. I have conducted research and have publications on bilingualism and multilingualism in education, language policy, heritage language education, statelessness, and family multilingualism. After long years of professional work in municipality, non-governmental organizations and community associations dedicated to promoting multilingualism in various contexts, I am excited to explore new terrains in academia, grow together intellectually, and contribute to efforts for social transformation and justice.

Nicole Marinaro

My name is Nicole Marinaro, and I did my PhD at Belfast’s Ulster University’s School of Applied Social and Policy Sciences, focusing on addressing communication difficulties between patients and healthcare professionals. My research interests include language policy, sociolinguistics and linguistic justice, with a focus on the inclusion of linguistically diverse speakers. I am also passionate about language teaching and dissemination of academic knowledge.

I am particularly excited to become part of a diverse and interdisciplinary team, to learn from each other over the next years and to make a real contribution to a more linguistically just society.

Olga Vlasova

My name is Olga Vlasova. My research journey started in Prague at the Charles University where I obtained my BA degree in sociology. Later, I completed my Master’s degree in social policy at the University of Bremen and University of Amsterdam. During these years I have been contributing to research in the fields of migration and labour studies, with a particular focus on solidarity practices with migrant workers in the European labour markets. Apart from that, I’m a passionate volunteer and help newcomers with their integration into Hamburg society.

One thing my life journey has taught me is: “Be brave and follow your ideas and passions!”

What’s next?

Over the next 4 years, our work will be in the following five areas:

- We will conduct a set of interlinked ethnographies to better understand linguistic diversity and social participation across the lifespan

- We will make a novel methodological and epistemological contribution related to qualitative multilingual data sharing

- We will build capacity in international networked education research (see also WERA IRN Literacy in Multilingual Contexts)

- We will work with community stakeholders to help improve language policies and practices and make institutional communication more accessible

- We will share knowledge and contribute to a greater valorization of linguistic diversity

Along the way, we will keep you all posted, of course. Watch this space!

Early next year, we will also advertise another researcher position on our team so that’s another reason to follow our work

Related content

Alexander-von-Humboldt Professorship Awards 2025

]]>

The international research network “Literacy in Multilingual Contexts” builds on the “Next Generation Literacies” network

The World Education Research Association (WERA) recently announced the launch of seven new International Research Networks (IRNs) and we are pleased to share that “Literacy in Multilingual Contexts” is one of them.

What is a WERA IRN?

The WERA IRN initiative brings together global teams of researchers through virtual communication and other channels to collaborate in specific areas of international importance. “Literacy in Multilingual Contexts” joins a growing list of IRNs, contributing to the vision of WERA. The purpose of IRNs is to synthesize knowledge, examine the state of research, and stimulate collaborations or otherwise identify promising directions in research areas of worldwide significance. IRNs are expected to produce substantive reports that integrate the state of the knowledge worldwide and set forth promising research directions.

What does the IRN “Literacy in Multilingual Contexts” do?

The IRN “Literacy in Multilingual Contexts” aims to initiate and extend international collaborative research on literacy in the context of language diversity and migration. The joint focus is on literacy development and practice in multiple languages. Drawing on varied and complementary expertise from Europe, Australasia, Africa and North America, the objectives are:

- to enhance knowledge on literacy and student diversity

- to trace tendencies that go beyond one national, regional or local context

- to examine literacy development across the life-course

- to critically discuss the implications of research findings for policy and practice

Literacy is a foundation for participation in complex societies. The proposed research therefore also contributes to pathways to equity. The network’s activities will reach fundamental theoretical insights, which may be transferred to concepts of teaching/learning in educational institutions. This intervention research will attempt to generalise characteristics of successful multilingual literacy development to be adapted to specific contexts. The proposed IRN comprises senior, experienced and early career scholars (incl. PhD students), aimed towards international and intergenerational knowledge generation.

Literacy as a resource

At the heart of our network is the idea that multilingual literacy is a resource to be celebrated. Literacies across languages and scripts empower learners to create knowledge, to navigate education systems, and to participate fully in social and cultural life.

Members of the network bring expertise from early childhood to higher education, from family and community contexts to digital and AI-mediated literacies. Our shared vision is to develop research that responds to the multilingual realities of migration, mobility, and global diversity.

Building on the “Next Generation Literacies” network

The “Literacy in Multilingual Contexts” network has grown out of the Next Generation Literacies initiative, an international network of researchers working at the intersection of social participation and linguistic diversity.

Based on the trilateral partnership of Fudan University (China), Hamburg University (Germany) and Macquarie University (Australia), Next Generation Literacies brought together an interdisciplinary group of established and emerging researchers to build a truly global network.

After funding for the Next Generation Literacies network ended in 2024, the IRN “Literacy in Multilingual Contexts” keeps that spirit of collaboration alive, while also widening the circle: we are now connected with colleagues from the Network on Language and Education (LeD) in the European Educational Research Association (EERA) and with other WERA initiatives. Under this new umbrella, we will scale up our efforts and make a stronger impact together.

Network Conveners

The network is convened by

- Irina Usanova (University of Hamburg; Lead Convenor)

- Francis M. Hult (UMBC)

- Ingrid Piller (University of Hamburg & Macquarie University)

- Yongyan Zheng (Fudan University)

- Harkaitz Zubiri-Esnaola (University of the Basque Country)

Together with network members, we bring expertise spanning literacy research across continents and research traditions.

Kick-off meeting

On September 24, 2025, we came together on Zoom across many different time zones and continents to virtually celebrate the official launch of the Literacy in Multilingual Contexts IRN.

The kick-off meeting felt like both a reunion and a new beginning: familiar faces from the Next Generation Literacies network reconnecting, and new colleagues from around the world joining the conversation. Together, we are building a vibrant global community of researchers committed to understanding how literacy develops and thrives in multilingual settings. For all of us, it was a reminder of how much we can achieve when we put our multilingual realities at the center of literacy research.

What’s next?

Over the next three years (2025–2028), we will:

- review the state of research on multilingual literacies

- analyze existing datasets across different contexts

- share our work in joint events and publications

- build a sustainable international community dedicated to literacy in diversity

To make this vision concrete, members are invited to join thematic working groups. Topics include multilingual literacy in early childhood, in higher education, in Indigenous contexts, CLIL, multilingual writing and AI, and multilingual policy. Sounds interesting?

An open invitation

The energy of our first meeting showed just how much can be achieved when we bring our different perspectives together. The IRN “Literacy in Multilingual Contexts” is open to any researcher working in these areas. If you are interested in joining, please send your inquiry to Dr Irina Usanova.

Related content

]]>

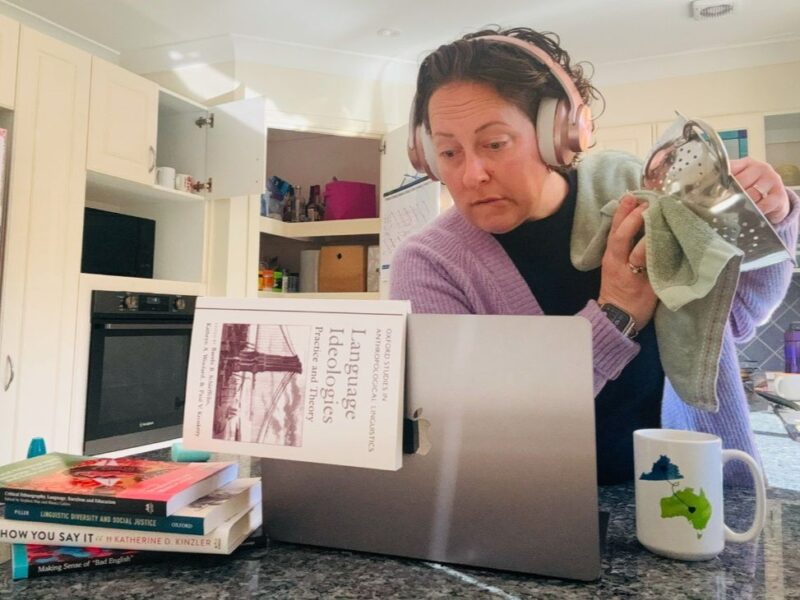

Being an academic mom has given Brynn a huge head start when it comes to managing her supervisors (Image credit: Brynn Quick)

You know that feeling you get in your stomach when you’ve climbed to the top of a rollercoaster, and you look down to see that first huge drop that’s rapidly approaching? That’s exactly what it can feel like to be at the beginning of your PhD. You have a vague idea about the direction that the rollercoaster track will take, but you also know that there will probably be twists, turns and loops (plus some screams and tears) that you can’t anticipate yet.

So, let’s talk about how to make that PhD rollercoaster ride as smooth as possible while also acknowledging that some upside-down moments are inevitable.

One of the most crucial elements of your PhD is your relationship with your supervisor. We’ve all heard the horror stories (The Thesis Whisperer Professor Inger Mewburn has compiled many!). Some PhD students experience bullying, harassment and outright abuse from their supervisors. We all want to avoid a toxic supervisor/student relationship, so it’s vital that every PhD student has a firm idea of how to build and maintain a partnership of trust with their supervisor.

I’m very lucky to have three fabulous supervisors on my team (Distinguished Professor Ingrid Piller is my primary supervisor, and Dr. Hanna Torsh and Dr. Loy Lising are my associates). Recently, Ingrid asked me to talk to other members of our research group about how I “manage” my supervisors while I conduct my research.

In response, I created a slideshow with key principles. What I realised by examining my own management processes was that I hold two principles to be most important:

- Explicitly discuss your expectations of your supervisor, and your supervisor’s expectations of you.

- Honour your supervisor’s time, and they will honour yours.

Let’s talk about these in more detail.

Setting Expectations

We’ve all heard about how communicating clear and mutually-agreed-upon expectations in marriages can lead to healthy partnerships, but many of these same communication principles also apply to working (and therefore, supervisor/supervisee) relationships.

You might send your supervisor a thesis chapter that you’ve just written, and you may assume that they will be able to email you with feedback within a week. However, what you might not know is that your supervisor is also writing their own research paper, preparing a lecture, working on a grant application and getting ready to present at a conference in two weeks.

Therefore, it’s incredibly important that you ask about expectations when you send that chapter. In your email with your thesis chapter, tell your supervisor how many pages (or words) you are sending. Tell them if it’s a first draft, a ninth draft, which changes you have highlighted, what uncertainties you have, etc. Explicitly tell them what task you will work on while you are waiting for their feedback (supervisors love productivity!).

Ask them what date will work with their busy schedules for you to expect feedback by, then trust that they will get back to you by that date. In clearly and explicitly communicating an expectation, you both avoid assuming that the other person has the same expectation that you do, and that reduces the chances of a big misunderstanding down the track.

Another element of setting expectations includes setting and managing expectations of yourself as the PhD student. During our undergraduate and even master’s by coursework degrees, it is often the professor or lecturer who is acting in the role of “manager”. They set reading tasks, and we do them. They assign a 4,000-word essay, and we write it. They tell us to be in class at 8:00am for a final exam, and we sleepily show up with an extra-large coffee. In these degrees, we get used to being told how to successfully be a student. As long as we follow directions, we will probably succeed.

During a research-based degree like a PhD, however, suddenly we become the managers, and this can be whiplash-inducing. Many of us have never had that type of teacher/student relationship before, so we have to learn quickly how to take the lead. This means acting as our own boss in one way – setting daily tasks for ourselves, tracking our own progress, troubleshooting, working towards both external and self-imposed deadlines, etc.

But at the same time, we have to be ready to adapt to expectations that our supervisor has of us and our work. This can be tough when we do eventually get used to being our own boss and managing our own work by ourselves for weeks at a time. This is exactly where clear communication comes into play. Begin and maintain your working relationship with your supervisor from a foundation of honesty and open conversations. If you both respectfully and clearly communicate expectations with each other, the PhD rollercoaster ride will have far fewer stomach-turning drops.

Honouring Time

Time is simultaneously something that we feel like we have far too much of and far too little of during a PhD. The idea of writing for literal years sometimes makes me want to curl into a ball, but also having “only” a few years to complete a PhD feels like a panic attack-inducing Herculean task. But do you know who else has a rough relationship with time? Your supervisor.

Like I said before, they might be teaching/researching/writing/lecturing while supervising. I myself teach every other semester, and doing that while researching (and let’s not even talk about trying to balance family life and parenting in that schedule somewhere!) can be exhausting. So, I honestly don’t know how my supervisors do all that they do in the limited time they have.

Therefore, I try as best I can to honour their time. This means that I keep my emails to them as organised and concise as possible. I come up with agendas for our supervision meetings and take notes during said meetings. Then I make sure to highlight any actionable items that we discussed, and I send the meeting notes to them with a summary of what actions each person has agreed to take by the next time we meet. I also try to figure out as much of the bureaucratic work that is involved in a PhD that I can before involving them (no but seriously, there is SO MUCH bureaucracy).

I have found that by taking these steps to be as proactive as possible and be mindful of my supervisors’ time constraints, they have been reciprocally mindful of mine.

Conclusion: We Can Make the PhD Rollercoaster Ride an Enjoyable One

I’m what we euphemistically call a “mature age student” (I just turned 40 a few weeks ago!). That is to say that this isn’t my first rodeo – I completed my bachelor’s degree in 2007 and was in the workforce and busy raising kids until re-entering academia in 2019. I think that, because of my age and life experiences, I have a unique perspective on the PhD process and working relationships. I truly believe that mutual respect and open communication between supervisors and supervisees is what will make this rollercoaster ride as easy as possible.

If you are on your own PhD rollercoaster, I hope that reading this post will give you the confidence to put “managing up” policies into practice. May your rollercoaster ride be as smooth as possible, and I hope you get to eat some fairy floss after it’s over.

]]>

Tazin speaks at Talent Day, Bangladesh Forum for Community Engagement

Every year, the Bangladesh Forum for Community Engagement in Sydney, Australia hosts an event called ‘Talent Day’ to acknowledge the achievements of primary and high school students in the Australian-Bangladeshi community. How does this interest a sociolinguist?

In so many ways – the interaction of multiple languages, the code-switching in the speeches, the expressions of heritage and identity in language use, the living examples of language shift through generations of migrants and so much more.

This year, though, my attention was taken by a request to give a short guest speech to the HSC graduates about to embark on their university journeys. My first dilemma was determining what meaningful contribution, as a second year PhD student, I could make. Which part of my university experience could I share? I decided to talk about my PhD supervisors and share two experiences that, for me, underlined the significance of language itself.

I told them about the lecture that Dr. Loy Lising delivers on the first day of class for our students. In the process of introducing me and the other members of the teaching team, she brings up the slide about communicating with us. But before the technical details, she implores the students to remember our common humanity when communicating with teachers. She explains that the use of our shared courtesies, such as “Dear [teacher’s name]”, “could you”, “thank you” acknowledge that a student and a teacher are two human beings communicating with one another.

From Dr. Lising’s words, I extrapolated that approaching someone more learned with humility confers dignity to both the teacher and the student and if anything, reminds one of the humility that should be cultivated in the pursuit of learning.

I then spoke about my first time as a student of Distinguished Professor Ingrid Piller, when I was doing my Masters of Applied Linguistics. It was time for the final assignment and before giving us the details, she displayed an image of a Persian rug. She directed us to the intricate parts that were woven, bit by bit, to produce something so beautiful.

Her next request was for us to write her a “beautiful” assignment. To achieve this, she asked us to remember the great privilege of higher education, which so many others have been and continue to be deprived of. We were reminded of our moral obligation to use our learning to contribute to society and the first step was to dedicate our attention to writing a good assignment – to remember the privilege of being able to write one.

Her next request was for us to write her a “beautiful” assignment. To achieve this, she asked us to remember the great privilege of higher education, which so many others have been and continue to be deprived of. We were reminded of our moral obligation to use our learning to contribute to society and the first step was to dedicate our attention to writing a good assignment – to remember the privilege of being able to write one.

I had never had an assignment presented quite like this before!

Conceptualising and expressing the act of learning as a privilege and the production of work as beautiful was yet another exercise in humility, a reminder of the very significant role that our teachers play in shaping our minds, and an acknowledgement of the purpose of higher education.

Towards the end of my speech, I realised I had given the students a series of stories and I wanted to explain why I had done this.

To be meaningful, university and higher education must be a journey of purpose, guided by our teachers and mentors who nurture our potential to contribute to the world. Ultimately, the university journey symbolises the lifelong commitment to learning from those who are more learned and passing it on to those that follow.

]]>

Tazin and Brynn, two of our enthusiastic podcast hosts

Editor’s note: Time flies: the Language-on-the-Move Podcast in collaboration with the New Books Network just turned one! Time to celebrate and reflect!

We celebrate a passionate team of hosts who created 43 insightful episodes about language in social life which have been downloaded 57,000 times across a range of platforms.

By download numbers, our top-5 episodes were:

- Muslim Literacies in China: Tazin Abdullah in conversation with Ibrar Bhatt

- Can we ever unthink linguistic nationalism? Ingrid Piller in conversation with Aneta Pavlenko

- Politics of language oppression in Tibet: Tazin Abdullah in conversation with Gerald Roche

- Making sense of “Bad English:” Brynn Quick in conversation with Elizabeth Peterson

- Lies we tell ourselves about multilingualism. Ingrid Piller in conversation with Aneta Pavlenko

Providing a service to our communities by sharing knowledge about intercultural communication, language learning and multilingualism in the context of migration and globalization is a key benefit of the Language-on-the-Move Podcast.

Another benefit accrues to our hosts who get to chat with key thinkers in our field. In this post, two of our hosts, Brynn Quick and Tazin Abdullah, share their reflections on the occasion of our 1st birthday. Enjoy and here’s to many more milestones!

***

Brynn Quick and Tazin Abdullah

***

Over the past year, many of us on the Language on the Move Team have been excitedly hosting podcasts about a wide range of topics in language and social life! As we dive into recording and producing our podcasts for the year ahead, we would like to share why this continues to be a rich and rewarding experience for us as PhD students at the beginning of our research journeys.

- Wider horizons: Sounds cliché but oh, so true! Each time we host a podcast, we spend a significant amount of time doing background research. We research our guests, their interests, and their work. The opportunity created for reading is amazing. Not only do we dip our toes into the vast ocean that is all things language, we learn new things to enhance our own research and add to our reference lists!

- Bigger networks: We establish relationships with our guests and connect with others in their networks. Our guests are great – they stay in touch! As the podcast is promoted on various platforms, we make connections with linguists around the world and are able to remain updated on developments in our field and directions that different researchers are taking.

- Informal mentors: Did we mention our guests are great? Our guests indulge us in lively and interesting conversations not just during the podcast but also off air. Every guest shares their experiences, offers us advice and stays open to us reaching out if we have any questions on their area of expertise or if we need to understand some part of the academic journey.

- Technical skills: Who knew how much work goes into the editing and production of a podcast episode? But this has also been a great learning experience, dabbling with technology and learning the ins and outs of various platforms – another transferable skill for emerging researchers.

- Successful collaboration: The podcast is just one more example of how collaboration between fellow researchers results in an overall increase in both productivity and learning. Many times, we have reflected amongst ourselves about the way our podcast works. We support, mentor and acknowledge each other and, like a feel-good movie, are left wanting to collaborate some more.

- Future collaborations: And yes, it has opened doors for us to future collaborations, to be able to reach out through our now wider networks and pursue our wide-ranging interests in linguistics and adjacent disciplines.

- Non-traditional research outputs: Finally, what we love looking at – our updated research output lists every time a podcast drops! And an added bonus for those of us who prefer talking about research rather than writing about it, this format speaks right to us! As non-traditional research outputs, podcasts have offered us a practical way for us to engage with our learning in real-world settings, to use and develop our various skills, and contribute to research at the same time.

We give our podcast hosting experience a 5-star rating! If you enjoy the Language on the Move podcasts, please leave us a 5-star review on your podcast app of choice, and recommend the Language-on-the-Move Podcast and our partner the New Books Network to your students, colleagues, and friends.

Full list of episodes published to date

- Episode 43: Multilingual crisis communication: Tazin Abdullah in conversation with Li Jia (22/01/2025)

- Episode 42: Politics of language oppression in Tibet: Tazin Abdullah in conversation with Gerald Roche (14/01/2025)

- Episode 41: Why teachers turn to AI: Brynn Quick in conversation with Sue Ollerhead (09/01/2025)

- Episode 40: Language Rights in a Changing China: Brynn Quick in conversation with Alexandra Grey (01/01/2025)

- Episode 39: Whiteness, Accents, and Children’s Media: Brynn Quick in conversation with Laura Smith-Khan (24/12/2024)

- Episode 38: Creaky Voice in Australian English: Brynn Quick in conversation with Hannah White (18/12/2024)

- Episode 37: Supporting multilingual families to engage with schools: Agi Bodis in conversation with Margaret Kettle (20/11/2024)

- Episode 36: Linguistic diversity as a bureaucratic challenge: Ingrid Piller in conversation with Clara Holzinger (17/11/2024)

- Episode 35: Judging refugees: Laura Smith-Khan in conversation with Anthea Vogl (02/11/2024)

- Episode 34: How did Arabic get on that sign? Tazin Abdullah in conversation with Rizwan Ahmad (30/10/2024)

- Episode 33: Migration, constraints and suffering: Ingrid Piller in conversation with Marco Santello (14/10/2024)

- Episode 32: Living together across borders: Hanna Torsh in conversation with Lynnette Arnold (07/10/2024)

- Episode 31: Police first responders interacting with domestic violence victims: Tazin Abdullah in conversation with Kate Steel (29/09/2024)

- Episode 30: Remembering Barbara Horvath: Livia Gerber in conversation with Barbara Horvath (10/09/2024)

- Episode 29: English Language Ideologies in Korea: Brynn Quick in conversation with Jinhyun Cho (08/09/2024)

- Episode 28: Sign Language Brokering: Emily Pacheco in conversation with Jemina Napier (30/07/2024)

- Episode 27: Muslim Literacies in China: Tazin Abdullah in conversation with Ibrar Bhatt (24/07/2024)

- Episode 26: Life in a New Language, Pt 6 – Citizenship: Brynn Quick in conversation with Emily Farrell (17/07/2024)

- Episode 25: Life in a New Language, Pt 5 – Monolingual Mindset: Brynn Quick in conversation with Loy Lising (11/07/2024)

- Episode 24: Language policy at an abortion clinic: Brynn Quick in conversation with Ella van Hest (05/07/2024)

- Episode 23: Life in a New Language, Pt 4 – Parenting: Brynn Quick in conversation with Shiva Motaghi-Tabari (03/07/2024)

- Episode 22: Life in a New Language, Pt 3 – African migrants: Brynn Quick in conversation with Vera Williams Tetteh (27/06/2024)

- Episode 21: Life in a New Language, Pt 2 –Work: Brynn Quick in conversation with Ingrid Piller (19/06/2024)

- Episode 20: Life in a New Language, Pt 1 – Identities: Brynn Quick in conversation with Donna Butorac (12/06/2024)

- Episode 19: Because Internet: Brynn Quick in conversation with Gretchen McCulloch (03/06/2024)

- Episode 18: Between Deaf and hearing cultures: Emily Pacheco in conversation with Jessica Kirkness (01/06/2024)

- Episode 17: The Rise of English: Ingrid Piller in conversation with Rosemary Salomone (21/05/2024)

- Episode 16: Community Languages Schools Transforming Education: Hanna Torsh in conversation with Joe Lo Bianco (07/05/2024)

- Episode 15: Shanghai Multilingualism Alliance: Yixi (Isabella) Qui in conversation with Yongyan Zheng (02/05/2024)

- Episode 14: Multilingual Commanding Urgency from Garbage to COVID-19: Brynn Quick in conversation with Michael Chestnut (27/04/2024)

- Episode 13: Making sense of “Bad English:” Brynn Quick in conversation with Elizabeth Peterson (13/04/2024)

- Episode 12: History of Modern Linguistics: Ingrid Piller in conversation with James McElvenny (10/04/2024)

- Episode 11: 40 Years of Croatian Studies at Macquarie University: Ingrid Piller in conversation with Jasna Novak Milić (08/04/2024

- Episode 10: Reducing Barriers to Language Assistance in Hospital: Brynn Quick in conversation with Erin Mulpur, Houston Methodist Hospital (26/03/2024)

- Episode 9: Interpreting service provision is good value for money. Ingrid Piller in conversation with Jim Hlavac (19/03/2024)

- Episode 8: What does it mean to govern a multilingual society well? Hanna Torsh in conversation with Alexandra Grey (22/02/2024)

- Episode 7: What can Australian Message Sticks teach us about literacy? Ingrid Piller in conversation with Piers Kelly (21/02/2024; originally published 2020)

- Episode 6: How to teach TESOL ethically in an English-dominant world. Carla Chamberlin and Mak Khan in conversation with Ingrid Piller (20/02/2024; originally published 2020)

- Episode 5: Can we ever unthink linguistic nationalism? Ingrid Piller in conversation with Aneta Pavlenko (19/02/2024; originally published 2021)

- Episode 4: Language makes the place. Ingrid Piller in conversation with Adam Jaworski (18/02/2024; originally published 2022)

- Episode 3: Linguistic diversity in education: Hanna Torsh in conversation with Ingrid Gogolin (17/02/2024; originally published 2023)

- Episode 2: Translanguaging: Loy Lising in conversation with Ofelia García (16/02/2024; originally published 2023)

- Episode 1: Lies we tell ourselves about multilingualism. Ingrid Piller in conversation with Aneta Pavlenko (15/02/2024)

The 3-Minute Thesis (3MT) competition is an opportunity for higher degree research students to present their research in 3 minutes. Normally, symposiums, conferences and seminars are some of the ways research students get to talk about their research. Unlike those presentation formats, the 3MT poses a unique challenge – an entire thesis has to be presented within 3 minutes and not a second over!

This year, the Applied Linguistics Association of Australia (ALAA) held its 3MT competition on 27th September, 2024 and Tazin Abdullah won first prize. She presented on her research on the Linguistic Landscape of Australian mosques titled “Observe overall cleanliness and sound mannerisms at all times!” – Regulating Australian Muslims in mosques and Islamic prayer spaces.

Tazin’s study examined regulatory signs from Australian mosques that gave readers instructions and stated prohibitions regarding behaviour in these places. What do these signs say about the communication practices within Australian Muslim prayer spaces? What languages do these signs use to communicate with readers? What linguistic and visual strategies do they employ to present rules and regulations?

Reference

Abdullah, Tazin. 2024. “Observe overall cleanliness and sound mannerisms at all times!” – Regulating Australian Muslims in mosques and Islamic prayer spaces. (MRes), Macquarie University.

Other 3MT videos by members of the Language on the Move team

- Brynn Quick, Curing Confusion

- Pia Tenedero, Communicating globally while working remotely

In the interview, Barbara reflects on the early years of her career as an American linguist in Australia in the 1970s, and how linguistics and language in Australia have changed since then.

The transcript was edited by Brynn Quick.

Update 23/09/2024: The audio is now available here or on your podcast app of choice.

***

Livia: So, you’re very difficult to google and to do background research on!

Livia: So, you’re very difficult to google and to do background research on!

Barbara: Really?! Whenever I look myself up, I start finding me all over the place (laughs).

Livia: I did find a couple of things about you, like the fact that you had actually studied in Georgetown and Michigan, and that you came over to Sydney in the 1970s. Then I was astounded to find that you were the second linguist at University of Sydney. It was just you and Michael Halliday.

Barbara: Yes, but he only got there a couple of months before me. It was the birth of the Linguistics Department.

Livia: Can you tell me a little bit about what it was like when the field was so young?

Barbara: Well, I guess the answer to the story is that my husband got a job here. He’s a geographer, and we were in Vancouver at the time in Canada. He was teaching at Simon Fraser, and I was teaching at the University of British Columbia. We were both lucky, those were both just jobs for a year or two. I was writing my dissertation at that point.

So, we started applying, and he applied to the University of Sydney, and he got the job! And I applied, and I was told by a number of people at the University of British Columbia, linguists, that I didn’t have a chance. That there was no chance, it was only going to be one other person hired. And Michael, you know had a wife, Ruqaiya Hassan, and everybody was sure that Ruqaiya would get the other job. So, I didn’t have very much hope, but then I got the job!

I was just so amazed that I got the job, and I found out from Michael later that it turned out that the reason I got the job is, he was very interested in starting a department that would combine both systemics and Labovian kinds of sociolinguistics. He thought somehow we’d be able to mesh in an interesting kind of way, having different interests and different ways of configuring what the major issues were.

But we had great overlaps because I was just as interested in applied linguistics, and Michael certainly was and wanted to build a department up as a place for both theoretical and applied interests. So, it was that it was very exciting times for us when we did both get jobs at the same university which didn’t seem like that was going to be possible at all, but it was!

Livia: How long were you at Sydney for?

Barbara: Until I retired. It was my only place until I retired in 1980-something or 1990-something. I know I retired early because in those days women could retire at 55, so it was when I turned 55 that I retired. But after that is when I got more interested in working with a friend of mine in Louisiana, and we worked together for 10 or 12 years after that.

Livia: You’re also a female scholar who migrated to Australia. How did that shape your research or your role as a researcher?

Barbara: I don’t know that being a female shaped my research. I was much more interested in social issues. The time when I was doing my master’s and PhD were times of great upheaval with the anti-Vietnam war situation. I spent some time in my master’s degree working with Mexican children in California. I collected data there, and so it was more an interest in social issues.

I found the linguistics of theoretical people like Chomsky, for instance, very interesting. I found that the kinds of questions and the way he was doing linguistics was so different from writing grammars of language, for instance, which was the main thing that linguists were doing at that point, describing languages that hadn’t been described. I didn’t mind that either, but I was really taken in by the more political sides of things, and so when Labov first published his dissertation which was only when I was still at the master’s level, I just thought, Oh! This is what I want. This brings social issues and linguistics together.

I thought he was asking questions about how language changes, and I was very interested in that as a theoretical question. If it was going on before and it’s going on now, can you observe it changing? And when they came up with these nice statistical means and then the data necessary for using those statistical means to look at language changes, I found that theoretically exciting.

Livia: So, did you have a very big research team helping you when you first did the nearly 200 interviews in the Sydney?

Barbara: No, no, no! Not at all. I mean, that story is kind of funny. When I came here and it was only Michael and me, I had no idea about how the university worked. It was very different from American universities. I didn’t know how different it was. Michael was much more familiar with it I suspect because of his English background.

I came over here thinking, oh my gosh I have to get tenure because in America you have to get tenure within your first six years or else you’re going to go to some other university. And we had moved all around the world, my husband and I and my two little children. When we get to Sydney we thought, we’re just going to stay there. We’re not going to move at all. So, then I thought I’ve got to get busy, so I applied for a grant to do New York City all over again, except in Sydney.

That first year we collected the data from the Anglos. The Italians and the Greeks were in the third year. So, the first year Anne Snell and I collected all the data (chuckles) and made the preliminary transcripts. I think we had money for getting transcripts typed, and we had money for Anne and me to run around all over Sydney trying to get interviews with people. Then Anne and I sat together in my living room at the end of the data collection period just listening to the tapes and checking with each other if we were all hearing the same thing.

Then I found out afterwards that there is no such thing as tenure. If they hire you, they hire you, and they’re not going to think about getting rid of you. Oh! All that work I did! It was very funny.

It was when my supervisor from Georgetown, Roger Shuy, came over for participating in a conference. He said, “Barbara, I’m going to ask Michael how you’re doing.” And I said, “Ok.” He asked Michael did he think I’d get tenure, and Michael said something like, “I don’t know! I don’t think they do tenure here.” (laughs). Oh dear!

So anyway, I was working really hard. I thought I needed to, but I think I would’ve done it anyway. I definitely have no regrets. I’m glad we worked that hard, but it did mean coming home from teaching at the university – because most of the interviews were done at night, they were done after people had dinner – so Anne and I both got home, fed our families, turned around, got in a car and went off somewhere.

Livia: So, let’s talk about your data. You had a lot of data. I read a quote of yours somewhere where you said it was amazing how much variation there was, and that you were really excited about that.

I actually went to the Powerhouse Museum yesterday, and I looked at the Sydney Speaks app. I didn’t get all of the questions right! One of the teaching points in the app was that unless you live and grew up in Sydney, you’re not likely to get a lot of these right. So, for you, who didn’t grow up in Sydney, as an initial outsider, I’m sure the language variation would have been fascinating for you to learn about, as well as all the social aspects behind it. There are differences in society despite the classlessness that Australia prides itself in.

Barbara: Yeah, and again, you know, I came over here totally understanding that what I was seeing was social class. I mean it’s just social class as far as I’m concerned. It wasn’t that much different except certain ethnicities were different and all that sort of thing.

I looked for the sociology in it, and I though ok I’ll do like Labov did. He just found a sociologist, and he just used whatever categories the sociologist did! I found one tiny article from the University of New South Wales, and it just wasn’t that useful, so in a way I kind of had to figure out for myself what I thought. In the book I talk about how you come up against problems, like for example you have somebody who owns a milk bar, you know, in terms of the working class-or the middle class or whatever. So, you know, I think the class thing is fraught, and it’s still fraught today. It’s not well defined, though it’s better defined than it used to be.

Livia: And in general, there are ideas about the categories we imagine that people fall into. There are so many assumptions and myths out there.

Barbara: Absolutely, but then even when you decide that somebody is either Italian, Greek or Anglo, even those titles are complicated. Very many people didn’t like me using the term Anglo because they would rather be called Australians. That’s the way people were talking about it then, that there were Australians, Italians and Greeks.

But I remember one Scottish person said how insulted he was to be put in with the Anglos. I said well I suppose you are, come to think of it. So yeah, it was kind of fraught. It’s not the easiest thing in the world to do, to come in as a real foreigner, and not really knowing very much about Australia at all before we came and then trying to jump in to something like this.

I guess the thing that helped a lot is anybody who I hired were Australians, so they could um tell me when I was really going off the rails. I felt more comfortable with the Greeks and the Italians because they were foreigners like me, so they had different ways of understanding Australia as well.

Livia: That’s fascinating, especially considering in sociolinguistics at the moment that researcher positionality is a very big topic and having to justify your own positionality and reflect on your influence in the interview.

Barbara: Yes, but you know I don’t understand how we would ever do studies of other peoples if we only had ourselves to look at, that is if everybody else was just like you. First of all, I wouldn’t have found very many Americans of my particular background, so I think you have to be cautious about these things.

But what I also think is that when you do a kind of statistical analysis in the way that I did, and when you see the patterns that resolve, you think something is generating those patterns. It’s probably the social aspects as well as the linguistic aspects. You need to always be conscious of what you’re doing, as I was, with class. I knew I had no right to be assigning class to people because not even, you know, Marxists do that. Even though they believe in class, absolutely, they don’t go along classifying people. They talk about members of the working class, but it’s kind of a broad sweeping hand kind of thing.

So, in terms of picking up on the linguistic variable that I looked at, I really depended upon Mitchell and Delbridge and their work before me. So, we knew the vowels were very important in Australian English. If you look at Labov’s work, vowels are the most likely changing features of a language, and then of course certain consonants come up as well.

Livia: You just brought up Arthur Delbridge. Let’s talk a little bit about your colleagues over the years, particularly also the colleagues you’ve met through the Australian Linguistic Society (ALS). Could you maybe tell me a little bit about your involvement with the ALS?

Barbara: I’m sure that I attended some ALS meetings from whenever I got here to whenever I left! But I didn’t attend after I retired. I don’t recall going to too many meetings, but early on it was a small group of people, as you can imagine. It was Delbridge and I’m not sure who else, but Delbridge for sure was a major person in the early stage in getting the whole thing going as far as I know.

It was a small group of people, a very friendly group of people who got together. It was the first time that I saw a group of students or university people who were interested in Aboriginal languages because we didn’t really have that in Sydney at first until Michael Walsh joined the faculty. So, I realised that, at least among young people, there was really the enthusiasm for Australian linguistics.

The meetings were always held at some university. We always lived in the dormitories together, so it was, you know, breakfast, lunch and dinner with a very friendly group of people. And there were good papers. You could listen to papers on Aboriginal languages, for instance, that I wasn’t getting from any other place, so that that was all very interesting.

When I first came here, John Bernard was very helpful to me, and I used his work as well on vowels in Australian English. Those were very fundamental. If I hadn’t had those as a base, I could not have done my work as quickly as I did, but because they’d worked on that for a long time, it was very helpful.

I also remember the systemics people, Jim Martin and Michael (Halliday), coming, and they had a harder time because I think there weren’t a sufficient number of them. There was Ruqaiya and Michael and Jim at first, but eventually, as you know, they got a sufficient number of people, and then they became very, very big.

Then it became the really, the major direction in the department. By the time I left, it was not the only direction. They would go on to certainly hire more people who are in sociolinguistics. Two or three different Americans came over to work, and others like Ingrid (Piller). So yeah, it’s expanded and now it’s a very different department from what it was when I was there.

The department was really small for those first ten or twelve years. We were very close. We used to plan weekends together where, you know, we’d go at the end of the year and we’d go off camping! We’d go somewhere together. The graduate students and the staff just did things together, and that was very nice. So, you made very warm relationships with many people who came from that era. Maybe it’s still the same way. It may still be wonderful.

When Michael Walsh came, it was important for him to come because we were getting to look like we weren’t an “Australian” bunch of people, so when Michael came at least he legitimised us because he was working on Aboriginal languages. He was an Australian, so we all learned how to be Australian from Michael.

Livia: Whatever “Australian” means nowadays, right? (laughs)

Barbara: Yeah, whatever that means. Well, I think of myself as practically Australian now, but nobody else does, so (laughs) that’s just the way it is.

Livia: What’s it like for you walking around, say, Glebe now and hearing all the variation in Australian English? Do you get very excited when you hear people speaking?

Barbara: I don’t think I want to go and do another study, no! No, no. I still like to listen. I feel that there’s some things that I could have pursued, and perhaps I should’ve. I’ve always felt, I keep telling this to every sociolinguist I ever meet in Australia, and that is that somebody needs to study the Lebanese community. The Lebanese community is going to be very, very interesting, and of course if you don’t capture it really soon, you know, it will –

Livia: Has no one done that?

Barbara: No, not really. I know of no major study now. Maybe somebody’s done it a little bit here and there, but I think that would be fascinating to study, so I keep trying to urge people to study the Lebanese community.

Livia: That’s interesting because they’re a fairly recent migrant group but not that recent.

Barbara: No, not that recent. They were when I when I was doing my studies. The Greeks and the Italians were the major groups that anybody ever talked about, so when you were talking about migrants you meant the Greeks and the Italians. But the Lebanese were becoming a force, particularly if you were doing applied linguistic work. If you were working with the schools, the most recent group to migrate in large numbers were the Lebanese. So, I felt even then that I couldn’t face doing another major work like that again. But every time we did get a new sociolinguist, I told them that they should be studying the Lebanese community.

Livia: Too bad I’m nearly finished with my thesis (both laugh). But to take you back to the ALS conference days – what do you remember of those?

Barbara: Bearing in mind I haven’t been to a meeting in many years, what I recall of them is that most of the papers were interesting. I do recall the social aspects of it, getting together with groups of people who are linguists and just talking among yourselves. That, to me, is the best part about meetings all together. Unless it’s somebody who’s absolutely giving a paper right on what you’re interested because then you’re just kind of sitting there absorbing and thinking. But actually talking to people, especially because, as I said, we were a small group at that point, so it was very personal and interactional. That’s the main thing that I think about when I think about the ALS.

Livia: I’m always told when you go to conferences that it’s good to be criticised or challenged in your ideas, or that out of failure come new ideas. I’m just wondering whether you recall a time when that happened to you, that you were maybe challenged in your ideas but that actually ultimately took you in a direction that was more fruitful?

Barbara: I think people treated me very well, so I don’t recall any criticism. No, there was criticism when my book first came out, but it was well-intended. In those days we really didn’t do those things publicly. Everybody was incredibly polite to everyone else, so even if you did think, “oh that was a stupid paper,” you wouldn’t say it, and you wouldn’t embarrass somebody with it. I think you might challenge them later over coffee, but it was a very polite society at that time.

This was unlike some of the American things that you go to where you get somebody in the audience who is just dying to “get you”, you know? That kind of thing was not a nice feeling. People treated me very well, and I know now from looking back that I came over here like a bull in a china shop in the sense of who was I to be coming here and taking on such a big project, and taking it on with the manner and attitude that I had? I know this now because I’ve been here long enough to know how you feel about people who come here, and suddenly they know everything about anything. So, I think I probably stepped on a few toes, partly out of innocence.

One of the reasons I really like Chomsky is that he is argumentative, and I don’t mind a good argument. Not a personal one, not one that’s vindictive or whatever, but I think being strong about what you feel or arguing about what you think is controversial – I think that’s healthy for any field. You need to be able to say, you know, I have a different opinion about that, or I think something else is working here.

I got a really nice letter from John Bernard, for instance, who took me to task for a number of things. He wrote me a very long letter. I appreciated the fact that he had put in all that time to respond. I didn’t necessarily agree with him, but I understood where he was coming from. I guess what I like about John Bernard is that even after that he was always very friendly to me. I never had any problems with him, so I hope he never took whatever I said argumentatively to heart (laughs).

Livia: It’s important to have a good scholarly debate without being personal.

Barbara: Yeah, I think so too. But I can imagine I might have the same reaction if somebody came over and redid my work and they’d only been here three months, and I could say, “What would you know?!” (laughs)

You know, it is true that one of the things was the class issue, that I imposed this class issue. I don’t know that he said I imposed it, but he really did want to make the point that class wasn’t as significant in Australia, and he was still supporting the notion that it was a matter of choice, that you could choose. That was so alien to me, and it is still kind of alien to me.

I think people don’t choose the dialect they speak. I think they speak the dialect they’re brought up in, and that doesn’t mean I don’t think people can’t change their dialect. I think they can if they want to, if they move somewhere else or if they, you know, get a PhD and become professor of Physics or something. I think they can move up and down, up and down. I think that can happen, but it was the word “choose”, I think, that that bothered me a lot. I couldn’t see kids deciding, “oh I’m not going to speak like that anymore,” because they probably haven’t even heard anybody speak any other way except on television, and how much do we get from television? Or radio, or that kind of thing? I don’t think that much. But I just- I came in at that moment, I think, before a lot of people would understand that choosing isn’t probably the right word or the right conception of how dialect changes, that- that you decide to speak a different way. Anyway, that’s my story, and I’m sticking to it! (chuckles)

Livia: Speaking of changes – you’ve been in Australian linguistics for a bit of a while. What are sort of the major changes that you’ve seen happening in the field?

Barbara: I can tell you about my department. There’s much more interest in descriptive language, grammatical description. That’s really very big in the Sydney department. What’s happening in the rest of the department, I’m just not familiar with.

The set up that Michael (Halliday) managed to create in the department is kind of there, but it has a very different flavour. It’s much more anthropological, what I would call anthropological linguistics. So, still interested in people, still interested in culture and language as well, and especially in studying the variety of languages. I think it’s probably a firmer basis for study than sociolinguistics, and even Michael’s kind of sociolinguistics works best, I think, if you’re a native speaker of the language. I mean, why else is it that we get so much work on English? Because it’s kind of an English-based theoretical position. When I go to meetings, I meet lots of people from Europe and various other places who are studying their own languages in a sociolinguistic manner. But anyway, I would be out of place, I think, in the department now because I’d be the only one doing that.

I’ve been going to the seminars this year, and they’re very interesting papers that are being given with a lot of really interesting and new (to me) people in the department. I know this honours student that I was telling you about, that I was mentoring this year. She is so enthusiastic, and yet there isn’t any real place in this department for her to pursue her work. She had to do a lot of work in figuring out how to collect data, how to interpret your own findings after you’ve done the statistical analysis, all that stuff. She had a real task ahead of her, and I’m glad to say that Catherine Travis has picked up some of my work with that.

I don’t know if you know, but I was about to get rid of all my tapes. I downsized about five years ago. I just decided I was going to downsize. I was not going to do any more research, so it was time to just clean up my house, and I came to those tapes that I had saved from all these years ago. I thought, ah I know somebody in the world would like to have these tapes eventually, but they were still on these little cassettes. They needed a lot of work done with them before they’d be useful to anybody anymore, so anyway she got in touch with me. I said to her, by the way if you have any interest at all in my tapes because I’m just about to ditch them – and she wrote back quickly, “Don’t! Don’t! I’ll be up-I’ll come up and pick them up!”. (laughs)

So, she did, and I’m so glad because she really is doing some great work down there. So, I hope my little honours student goes down there to finish her work because I think she’s so enthusiastic.

Livia: Coming back to Sydney Speaks – I was looking through the Sydney Speaks webpage and there seem to be quite a few projects that are reaching a wider population.

Barbara: Yes, there’s lots of stuff. They’re collecting more data. They seem to be interested in ethnic varieties of English, that sort of thing, so yeah! It’s a whole new revitalisation, I think, of the interest in ethnic varieties of English. There are so many new and large migrations that have happened since the Italians. I mean, the Italians and the Greeks – Leichhardt, for instance, it’s not there anymore. You can’t go there and see that whole row of Italian restaurants that you used to find. Now you go to buy your coffee where you’ve always been to buy your coffee, and it does not seem to be run by Italians anymore, that kind of thing. So yeah, no Greeks and Italians.

I think it’s probably the case that you need two generations. You need the parent generation and the teenager (more or less what I did) because I suspect by the time it gets to the third generation, it’s gone. They’re just Aussies, and they speak like Aussies, and you wouldn’t find anything very interesting. So, you’ve got to catch it when it’s there. Timing is everything.

Livia: Are you going to be attending the ALS conference in December? Are you able to make it?

Barbara: No, no, no. I’ve actually not been in linguistics for quite a while now. That’s why I was downsizing, and I had to face it that I hadn’t been doing anything, that’s it! Give it up! Yeah.

Livia: Well, given that the ALS would like some snippets, I was thinking – Are there any wishes you have for the linguistics society moving forward? For their 50th anniversary?

Barbara: I’m interested in all of these people who are doing the dynamics of language. When I started looking up Catherine and looking up various others and I see all these people are doing something called the dynamics of language. So, what do they mean by that? Well, you know, I doubt they are all Labovians. I guess I’d love to see the group of them getting together in a discussion of just that. What are the dynamics of language that you’re focussing on? What kind of theoretical issues are there? Do you have overlapping goals, or do you have a single set of goals? Does dynamics actually mean language change as it is associated with historical linguistics? Or does it just mean socially dynamic, like other people picking up your language? Or just the use of language? Or how many people still speak Polish? Or is that the dynamics of language? I’d love to see what people are thinking about with the dynamics of language. It’s obviously got people very interested, whatever it is. That’s what I would like I would like to see a discussion of.

Livia: In that vein of wishing things – do you have any advice for PhD and honours students pursuing linguistics?

Barbara: Be passionate about something, and purse that. I was passionate myself for a long time when I did my bachelor’s degree. I knew I wanted to do English and it was all literature. I knew that what I really like is grammar, but I had never heard the word linguistics before. It wasn’t until I went to Ethiopia and I was teaching at Haile Selassie, the first university (now, Addis Ababa University), that I met a group of linguists who had come over there. And I thought oh, Linguistics! That’s what I want to be, you know? Then I really pursued that afterwards, but yeah, find your passion.

I had a very strong kind of social commitment to making a good society, and language is really kind of right in the middle of that.

That’s such an easy cliché, but because, as I said, when I started off, I had a very strong kind of social commitment to making a good society, and language is really kind of right in the middle of that. What I loved about sociolinguistics is that you could easily go in between the more sophisticated theoretical issues as well as being right on the ground and saying here are some problems that we’ve got. How can we think about these things? So, I did a lot of work with schools, and I think being able to interact with your community for me, not everybody, but for me, that was a very important thing.

Livia: Yeah, I agree. I think it’s interesting that language keeps coming up in the media. People are grasping how complex it is, and it has complex social meanings behind it. I mean, most recently we saw this in the citizenship debates of some of the politicians. There were politicians making fun of each other, saying I don’t sound Greek, but everyone always says where are you from, and now I’m the most Aussie in the room.

Barbara: Yeah, absolutely. No, that’s not true of me because I can go to David Jones tomorrow and get up to pay for my goods, and the people will think I’m an American tourist. They’ll ask me how I find Sydney. So, it isn’t true of me. Nobody has ever, ever said that I was an Aussie. (laughs)

Livia: I’ll ask you maybe one last reflective thing. Thinking back to when you first started and you were involved with all these linguists, particularly in the ALS, what advice would you give to yourself?